America Is Hard to See | Art & Artists

May 1–Sept 27, 2015

America Is Hard to See | Art & Artists

Learn Where the Meat Comes From

14

Building upon the ethos of experimentation of the previous decade, many artists in the 1970s shifted away from making objects and began to embrace performative storytelling and body-oriented actions. Video technology—which was still in its infancy at the start of the decade—provided a groundbreaking new tool for personal expression, often giving voice to the disenfranchisement of women and people of color. While some of these artists were drawn to video’s formal and technical properties, others were among the generation of feminist artists who recognized the medium’s radical potential to appropriate the power structures of mass media. Suzanne Lacy’s Learn Where the Meat Comes From, for example, begins with the artist in a tastefully outfitted kitchen in a gentle parody of instructional cooking shows, such as the one popularized by Julia Child—and devolves into an absurdist, biting commentary on domestic work and the objectification of the female body. Lacy’s behavior alternately mimics that of both predator and prey, and by the end of the video the division between human and animal has all but dissolved; the hostess sits down to a properly set table complete with wine and salad and then proceeds to devour the cooked roast like a snarling, ravenous beast.

Other works in this chapter take up related concerns. Artists such as Eleanor Antin, Lynda Benglis, Joan Jonas, Cindy Sherman, and Hannah Wilke use their cameras—whether video or still—to confront themselves, exploring the boundaries of subjectivity. Others, including the Los Angeles−based collective Asco, Ulysses Jenkins, Howardena Pindell, and Martha Rosler work, like Lacy, to draw attention to the ways media shapes our perception of identity and to the inherent gender and racial biases that often accompany those depictions.

Below is a selection of works from this chapter.

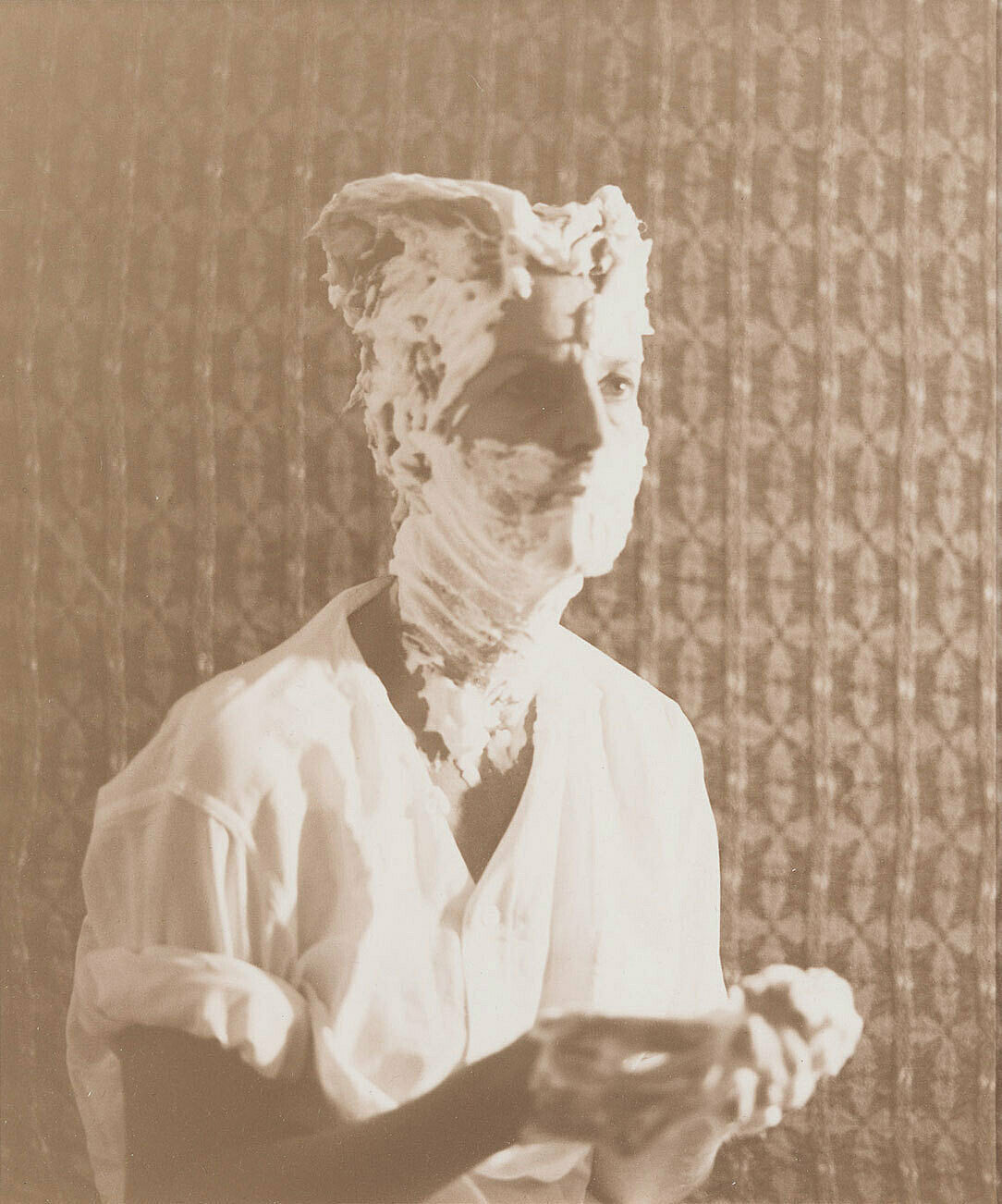

STURTEVANT (1924-2014), DUCHAMP MAN RAY PORTRAIT, 1966

In the mid-1960s, the artist Sturtevant began to make what she termed “repetitions” of artworks by contemporaries such as Jasper Johns, Claes Oldenburg, and Andy Warhol. She also reimagined numerous works by Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968), whose readymades were an important precedent for Conceptual art. Here she has restaged a theatrical 1924 portrait of Duchamp taken by his frequent collaborator, Man Ray. She replicated the way that Duchamp coated his face and neck in soapsuds, lathering her hair—as he had—into two stiff spikes that resemble the winged helmet of Mercury, the Roman messenger god. Through this re-creation, Sturtevant also echoed Duchamp’s ambiguously gendered self-representations, in which he frequently appeared in the guise of his female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy.

None of Sturtevant’s works look exactly like the originals (in this instance, to begin with, she didn’t resemble Duchamp). They are not copies but interpretations, alternative versions of “masterworks” that undercut conventional ideas of originality and authenticity—ideas that, in this case, the quoted work also challenged.

Artists

- Berenice Abbott

- Michele Abeles

- Vito Acconci

- Ansel Adams

- Robert Adams

- Carl Andre

- Kenneth Anger

- Eleanor Antin

- Diane Arbus

- Cory Arcangel

- David Armstrong

- Richard Artschwager

- Ruth Asawa

- Asco

- Charles Atlas

- Lutz Bacher

- Peggy Bacon

- Jo Baer

- Alex Bag

- Malcolm Bailey

- Lamar Baker

- John Baldessari

- Alvin Baltrop

- Lewis Baltz

- Matthew Barney

- Richmond Barthé

- Jean-Michel Basquiat

- Romare Bearden

- Cecil Beaton

- Robert Beavers

- Robert Bechtle

- Ericka Beckman

- Larry Bell

- George Bellows

- Lynda Benglis

- Thomas Hart Benton

- Wallace Berman

- Bernadette Corporation

- Judith Bernstein

- Huma Bhabha

- David Bienstock

- Henry Billings

- Ilse Bing

- Dara Birnbaum

- Nayland Blake

- Oscar Bluemner

- Peter Blume

- Lee Bontecou

- Jonathan Borofsky

- Louise Bourgeois

- Margaret Bourke-White

- Carol Bove

- Mark Bradford

- Stan Brakhage

- Robert Breer

- Patrick Henry Bruce

- Bernarda Bryson Shahn

- Charles Burchfield

- Jacob Burck

- Chris Burden

- Scott Burton

- Mary Ellen Bute

- Paul Cadmus

- John Cage

- Alexander Calder

- Cameron

- Luis Camnitzer

- Peter Campus

- James Castle

- Elizabeth Catlett

- Maurizio Cattelan

- Vija Celmins

- John Chamberlain

- Paul Chan

- Sarah Charlesworth

- Ayoka Chenzira

- Chryssa

- Larry Clark

- Chuck Close

- Sue Coe

- Anne Collier

- Bruce Conner

- Joseph Cornell

- Eldzier Cortor

- Miguel Covarrubias

- John Covert

- Ralston Crawford

- E.E. Cummings

- Imogen Cunningham

- John Currin

- John Steuart Curry

- Allan D'Arcangelo

- James Daugherty

- Emma Lu Davis

- Stuart Davis

- Roy DeCarava

- Jay DeFeo

- Willem de Kooning

- Walter De Maria

- Charles Demuth

- Maya Deren

- Jim Dine

- Mark di Suvero

- Arthur Dove

- Thomas Downing

- Elsie Driggs

- Guy Pène Du Bois

- Carroll Dunham

- Sam Durant

- Jimmie Durham

- Mabel Dwight

- William Eggleston

- Nicole Eisenman

- Wharton Esherick

- Walker Evans

- Kevin Jerome Everson

- Loretta Fahrenholz

- Andreas Feininger

- Lyonel Feininger

- Duncan Ferguson

- Rafael Ferrer

- Paul Fiene

- Morgan Fisher

- John B. Flannagan

- Hollis Frampton

- Robert Frank

- Andrea Fraser

- LaToya Ruby Frazier

- Hermine Freed

- Jared French

- Lee Friedlander

- Brian Frye

- Charles Gaines

- Anna Gaskell

- GCC

- Gerald K. Geerlings

- Hugo Gellert

- Sandra Gibson

- Luis Gispert

- William Glackens

- Milton Glaser

- Robert Gober

- Nan Goldin

- Wayne Gonzales

- Felix Gonzalez-Torres

- Boris Gorelick

- Arshile Gorky

- Dan Graham

- William Gropper

- Nancy Grossman

- George Grosz

- Louis Guglielmi

- Philip Guston

- Walter Gutman

- Wade Guyton

- Hans Haacke

- Peter Halley

- David Hammons

- Keith Haring

- Rachel Harrison

- Marsden Hartley

- David Hartt

- David Haxton

- Sharon Hayes

- Al Held

- Robert Henri

- Carmen Herrera

- Eva Hesse

- Lewis Hine

- Nancy Holt

- Jenny Holzer

- Edward Hopper

- Roni Horn

- Earl Horter

- Alex Hubbard

- Peter Hujar

- Victoria Hutson Huntley

- Richard Hunt

- Robert Indiana

- Abraham Jacobs

- Ulysses Jenkins

- Neil Jenney

- Candy Jernigan

- Jess

- Jasper Johns

- Rashid Johnson

- Ray Johnson

- William H. Johnson

- Joan Jonas

- Joe Jones

- Philip Mallory Jones

- Michael Joo

- Donald Judd

- Alex Katz

- On Kawara

- Mike Kelley

- Ellsworth Kelly

- Sister Corita Kent

- Rockwell Kent

- Karen Kilimnik

- William Klein

- Franz Kline

- Josh Kline

- Jeff Koons

- Lee Krasner

- Barbara Kruger

- Yasuo Kuniyoshi

- Yayoi Kusama

- Suzanne Lacy

- David Lamelas

- Dorothea Lange

- Liz Magic Laser

- Robert Laurent

- Louise Lawler

- Jacob Lawrence

- An-My Lê

- William Leavitt

- Zoe Leonard

- Alfred Leslie

- Howard Lester

- Sherrie Levine

- Herschel Levit

- Helen Levitt

- Norman Lewis

- Sol LeWitt

- Roy Lichtenstein

- Glenn Ligon

- Kalup Linzy

- Alvin Loving

- Lee Lozano

- Louis Lozowick

- George Luks

- Helen Lundeberg

- Len Lye

- Danny Lyon

- Stanton Macdonald-Wright

- Tala Madani

- Sylvia Plimack Mangold

- Man Ray

- Robert Mapplethorpe

- Christian Marclay

- Brice Marden

- Marisol

- Kyra Markham

- Reginald Marsh

- Agnes Martin

- Fletcher Martin

- Gordon Matta-Clark

- Cynthia Maughan

- Keith Mayerson

- Paul McCarthy

- John McCracken

- Adam McEwen

- John McLaughlin

- Josephine Meckseper

- Jonas Mekas

- Ana Mendieta

- Sam Middleton

- Aleksandra Mir

- Joan Mitchell

- Toyo Miyatake

- Lisette Model

- Donald Moffett

- Abelardo Morell

- Robert Morris

- Mark Morrisroe

- Gerald Murphy

- Elizabeth Murray

- Julie Murray

- Reuben Nakian

- Bruce Nauman

- Alice Neel

- Louise Nevelson

- Barnett Newman

- Isamu Noguchi

- David Novros

- Jim Nutt

- Chiura Obata

- Georgia O'Keeffe

- Claes Oldenburg

- Catherine Opie

- José Clemente Orozco

- Raphael Montañez Ortiz

- Alfonso Ossorio

- Tony Oursler

- Bill Owens

- Akosua Adoma Owusu

- Nam June Paik

- Jean Painlevé

- Gordon Parks

- Agnes Pelton

- I. Rice Pereira

- Raymond Pettibon

- Elizabeth Peyton

- Paul Pfeiffer

- Howardena Pindell

- Adrian Piper

- Horace Pippin

- Lari Pittman

- Jackson Pollock

- Liliana Porter

- Richard Pousette-Dart

- Richard Prince

- Nancy Elizabeth Prophet

- Noah Purifoy

- R. H. Quaytman

- Walid Raad

- Yvonne Rainer

- Christina Ramberg

- Robert Rauschenberg

- Charles Ray

- Luis Recoder

- Jeffrey Reed

- Robert Reed

- Earl Reiback

- Ad Reinhardt

- Hans Richter

- Faith Ringgold

- Dorothea Rockburne

- James Rosenquist

- Martha Rosler

- Theodore Roszak

- Susan Rothenberg

- Mark Rothko

- Edward Ruscha

- Morgan Russell

- Betye Saar

- David Salle

- Lucas Samaras

- Jacolby Satterwhite

- Peter Saul

- Matt Saunders

- Morton Schamberg

- Carolee Schneemann

- Dana Schutz

- Dread Scott

- George Segal

- Richard Serra

- Ben Shahn

- Joel Shapiro

- Paul Sharits

- Charles Sheeler

- Cindy Sherman

- Roger Shimomura

- Everett Shinn

- Amy Sillman

- Laurie Simmons

- Taryn Simon

- Lorna Simpson

- John Sloan

- David Smith

- Jack Smith

- Kiki Smith

- Robert Smithson

- Tony Smith

- Keith Sonnier

- Edward Steichen

- Ralph Steiner

- Frank Stella

- Joseph Stella

- Harry Sternberg

- Hedda Sterne

- Florine Stettheimer

- May Stevens

- Alfred Stieglitz

- John Storrs

- Michelle Stuart

- Sturtevant

- Wayne Thiebaud

- Alma Thomas

- Rirkrit Tiravanija

- George Tooker

- Bill Traylor

- Ryan Trecartin

- Trisha Brown Dance Company

- Anne Truitt

- Wu Tsang

- Richard Tuttle

- Cy Twombly

- Stan VanDerBeek

- Kara Walker

- Kelley Walker

- Carl Walters

- Andy Warhol

- Max Weber

- Weegee

- William Wegman

- Lawrence Weiner

- Tom Wesselmann

- H.C. Westermann

- Charles White

- Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney

- Jack Whitten

- Hannah Wilke

- Christopher Williams

- Sue Williams

- Fred Wilson

- Garry Winogrand

- William Winter

- Karl Wirsum

- David Wojnarowicz

- Jordan Wolfson

- Martin Wong

- Grant Wood

- Francesca Woodman

- Hale Aspacio Woodruff

- Christopher Wool

- Andrew Wyeth

- William Zorach