Alexander Calder

1898–1976

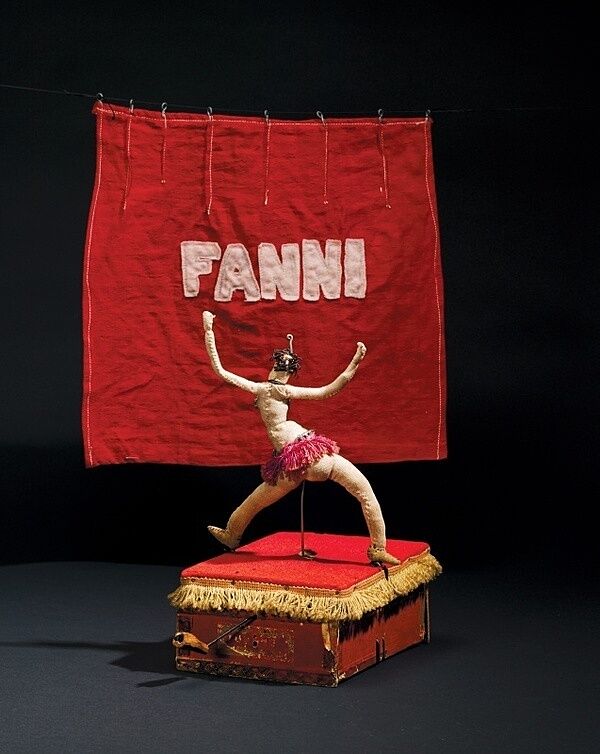

Across the course of more than six decades, Alexander Calder worked with materials ranging from thin pieces of wire to sheets of bolted steel, and experimented with scales and sites that encompassed everything from wearable jewelry to monumental outdoor sculpture. Calder had trained as a mechanical engineer, but he was an aspiring artist by the time he arrived in Paris in 1926, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, both well-known sculptors. There he began working on Calder’s Circus, an ensemble work comprising dozens of small movable figures and accompanying props made from wire as well as readily available, everyday items. Transporting the miniature circus in several suitcases, he gave performances with the creations in his studios and at the homes of friends and art patrons in Paris and New York. The artist served as impresario, narrating the acts in English and French, manipulating the figures, and providing musical accompaniment and sound effects. Adding acts over several years, he fabricated a ringmaster, trapeze artists, clowns, a belly dancer, and a sword swallower—often basing his characters on real circus performers—as well as numerous circus animals, including seals, a kangaroo, and a majestic, bearded lion.

Calder’s interest in the circus stemmed from a job he had held at a newspaper in New York, which sent him to illustrate the Ringling Brothers and Barnum and Bailey Circus in 1925. Describing his drawing technique, Calder spoke of his “knack for doing it with a single line,” barely lifting pen from paper. It was a technique he adapted to his small wire circus figures and later to a series of figurative sculptures. Using pliers to bend and contort his preferred medium, Calder created what he called “three-dimensional line drawing” in open wire portrait heads. His subjects included celebrities, politicians, sports stars, and fellow artists. He worked quickly, and while he made preparatory sketches for his portraits, he primarily improvised in the construction of these sculptures. “I think best in wire,” he explained. Calder met the French composer Edgard Varèse in 1930 and captured the details of his friend’s unique features in Varèse, using an economy of materials and gestures.

A formative visit to the Paris studio of the Dutch abstract painter Piet Mondrian, also in 1930, nonetheless convinced Calder to abandon such representational imagery in most of his work. He soon began making abstract paintings as well as sculptural constructions. Due to wartime shortages of metal, Calder’s sculptures from the early 1940s are predominantly composed of hand-carved wooden elements. In the Surrealist-inspired Wooden Bottle with Hairs, for example, an abstract piece that nonetheless retains some elements of representation, wood “hairs” dangle from tiny chains attached to wires that protrude from a bulbous wood form; the hairs quiver and vibrate with the slightest shifts in movement.

The sculptural forms for which Calder is best known, however, are his abstract “mobiles”—a term coined by his friend Marcel Duchamp—which were inspired by the kinetic qualities of his earliest pieces. Calder had initially generated movement in these works with manual cranks and motors but soon discovered that natural air currents alone could set the traditionally stationary art form into motion. “Why must art be static?” he famously queried. “The next step in sculpture is motion.” For many of his mobiles, including Big Red, Calder cut flat, biomorphic shapes from sheet metal, painted the components black, white, or one of the primary colors, and attached the segments to supporting rods. He secured his mobiles to bases, mounted them to walls, and suspended them from the ceiling, where they would be subject to air currents. Calder controlled the range of movements of his mobiles through carefully calibrated systems of weights and balances. The full composition of Big Red spins slowly through 360 degrees, while its subsidiary offshoots rotate independently, resulting in a captivating and unpredictable dynamism.

Dana Miller and Adam D. Weinberg, Handbook of the Collection (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2015), 84–86.

Introduction

Alexander "Sandy" Calder (; July 22, 1898 – November 11, 1976) was an American sculptor known both for his innovative mobiles (kinetic sculptures powered by motors or air currents) that embrace chance in their aesthetic, his static "stabiles", and his monumental public sculptures. Calder preferred not to analyze his work, saying, "Theories may be all very well for the artist himself, but they shouldn't be broadcast to other people." His father, Alexander Stirling Calder, and grandfather, Alexander Milne Calder, were also sculptors.

Wikidata identifier

Q151580

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed February 16, 2026.

Introduction

Calder graduated from Stevens Institute of Technology in 1919 with a degree in mechanical engineering. After taking classes at the Arts Students League, he became a freelance artist and illustrator, and published a book titled Animal Sketching. In the 1920s, Calder began traveling to Paris, where he was exposed to modernist tendencies in art. In 1930, after visiting Piet Mondrian's studio, where he was impressed by the studio environment, he began to create Comment on works: abstract, moving constructions, coined “mobiles” by Marcel Duchamp in 1931, for which he is most known. From the 1930s onward, Calder divided his time between trips abroad and his home in Roxbury, Connecticut, and as his commissions grew more frequent, his mobiles became increasingly gigantic. Examples are Flamingo, the stabile at Federal Center Plaza in Chicago, and L’Araignée rouge, at the Rond Point de La Défense Métro station in Paris.. Comment on works: abstract

Country of birth

United States

Roles

Artist, designer, illustrator, lithographer, painter, sculptor, tapestry designer

ULAN identifier

500007824

Names

Alexander Calder, Calder, Sandy Calder

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License. Accessed February 16, 2026.