Diane Arbus

1923–1971

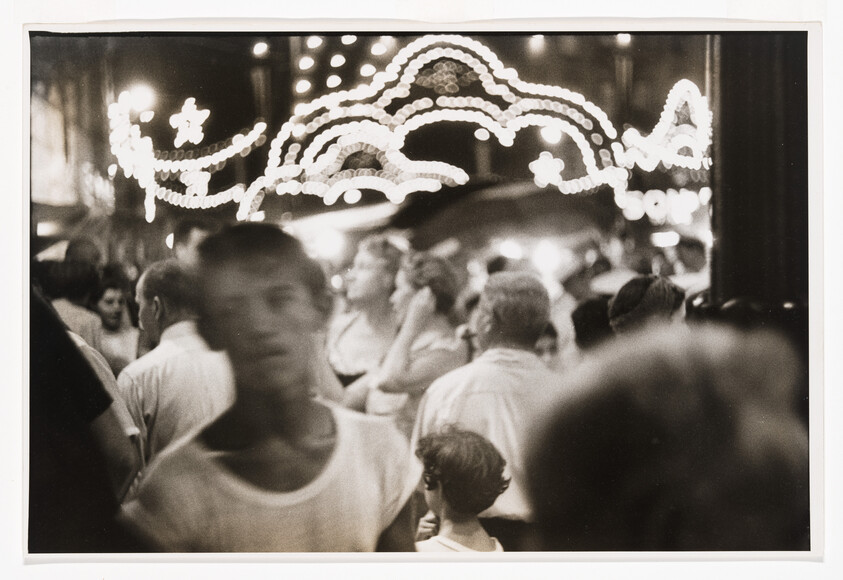

Diane Arbus’s photographs convey her unique vision of a time and a place— the period from approximately 1958 to 1971, primarily in and around New York— through intimate portraits of an array of strangers, acquaintances, and relations. Arbus wrote: “For me the subject of the picture is always more important than the picture. And more complicated.” The daughter of a wealthy New York family, Arbus became involved in photography with her husband, and the couple established a fashion photography business in 1946. She concurrently pursued her own photographs, but study with the groundbreaking photographer Lisette Model in the late 1950s precipitated a turning point in her work. In 1959 Arbus left her husband, moved to Greenwich Village, and began to concentrate on street photography of people she encountered throughout Manhattan; some of these images, taken with a 35mm camera, were published as photo essays in Esquire and Harper’s Bazaar magazines. Arbus’s mature style developed after 1963, when she used a medium-format Rolleiflex camera, which resulted in a distinctive square format, and often a strobe.

In Patriotic Young Man with a Flag, N.Y.C., Arbus isolates a demonstrator at a pro–Vietnam War rally in dramatic close-up, the harsh flash capturing his contorted expression, which, juxtaposed with a button declaring “I’m Proud,” offers a discomfiting vision of patriotism. In another distinctly American portrait, A family on their lawn one Sunday in Westchester, N.Y. presents a suburban family on their lawn; “The parents,” Arbus wrote, “seem to be dreaming the child and the child seems to be inventing them.” Although she worked for just over a decade (she committed suicide in 1971), Arbus produced some of the most searing images in the pantheon of photography.

Introduction

Diane Arbus (; née Nemerov; March 14, 1923 – July 26, 1971) was an American photographer. She photographed a wide range of subjects including strippers, carnival performers, nudists, people with dwarfism, children, mothers, couples, elderly people, and middle-class families. She photographed her subjects in familiar settings: their homes, on the street, in the workplace, in the park. "She is noted for expanding notions of acceptable subject matter and violates canons of the appropriate distance between photographer and subject. By befriending, not objectifying her subjects, she was able to capture in her work a rare psychological intensity."

In his 2003 New York Times Magazine article, "Arbus Reconsidered", Arthur Lubow states, "She was fascinated by people who were visibly creating their own identities—cross-dressers, nudists, sideshow performers, tattooed men, the nouveaux riches, the movie-star fans—and by those who were trapped in a uniform that no longer provided any security or comfort." Michael Kimmelman writes in his review of the exhibition Diane Arbus Revelations, that her work "transformed the art of photography (Arbus is everywhere, for better and worse, in the work of artists today who make photographs)". Arbus's imagery helped to normalize marginalized groups and highlight the importance of proper representation of all people.

In her lifetime she achieved some recognition and renown with the publication, beginning in 1960, of photographs in such magazines as Esquire, Harper's Bazaar, London's Sunday Times Magazine, and Artforum. In 1963 the Guggenheim Foundation awarded Arbus a fellowship for her proposal entitled, "American Rites, Manners and Customs". She was awarded a renewal of her fellowship in 1966. John Szarkowski, the director of photography at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City from 1962 to 1991, championed her work and included it in his 1967 exhibit New Documents along with the work of Lee Friedlander and Garry Winogrand. Her photographs were also included in a number of other major group shows.

In 1972, a year after her suicide, Arbus became the first photographer to be included in the Venice Biennale where her photographs were "the overwhelming sensation of the American Pavilion" and "extremely powerful and very strange".

The first major retrospective of Arbus' work was held in 1972 at MoMA, organized by Szarkowski. The retrospective garnered the highest attendance of any exhibition in MoMA's history to date. Millions viewed traveling exhibitions of her work from 1972 to 1979. The book accompanying the exhibition, Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, edited by Doon Arbus and Marvin Israel and first published in 1972, has never been out of print.

Wikidata identifier

Q234608

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed January 30, 2026.

Introduction

Born into a prominent New York Jewish family; her brother was poet Howard Nemerov. She worked with her husband on fashion photography. Later she separated from him and began her own career. Arbus' best known work investigates societies' frailties in portraits of outsiders, notably circus freaks, the mentally handicapped, transvestites, and nudists. She is noted for expanding notions of acceptable subject matter and violates canons of the appropriate distance between photographer and subject. By befriending, not objectifying her subjects, she was able to capture in her work a rare psychological intensity. She was troubled by depression throughout her life and committed suicide in 1971.

Country of birth

United States

Roles

Artist, photographer

ULAN identifier

500012758

Names

Diane Arbus, Diane Nemerov Arbus, Diane Nemerov, Diane née Nemerov

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License. Accessed January 30, 2026.