Arshile Gorky

c. 1904–1948

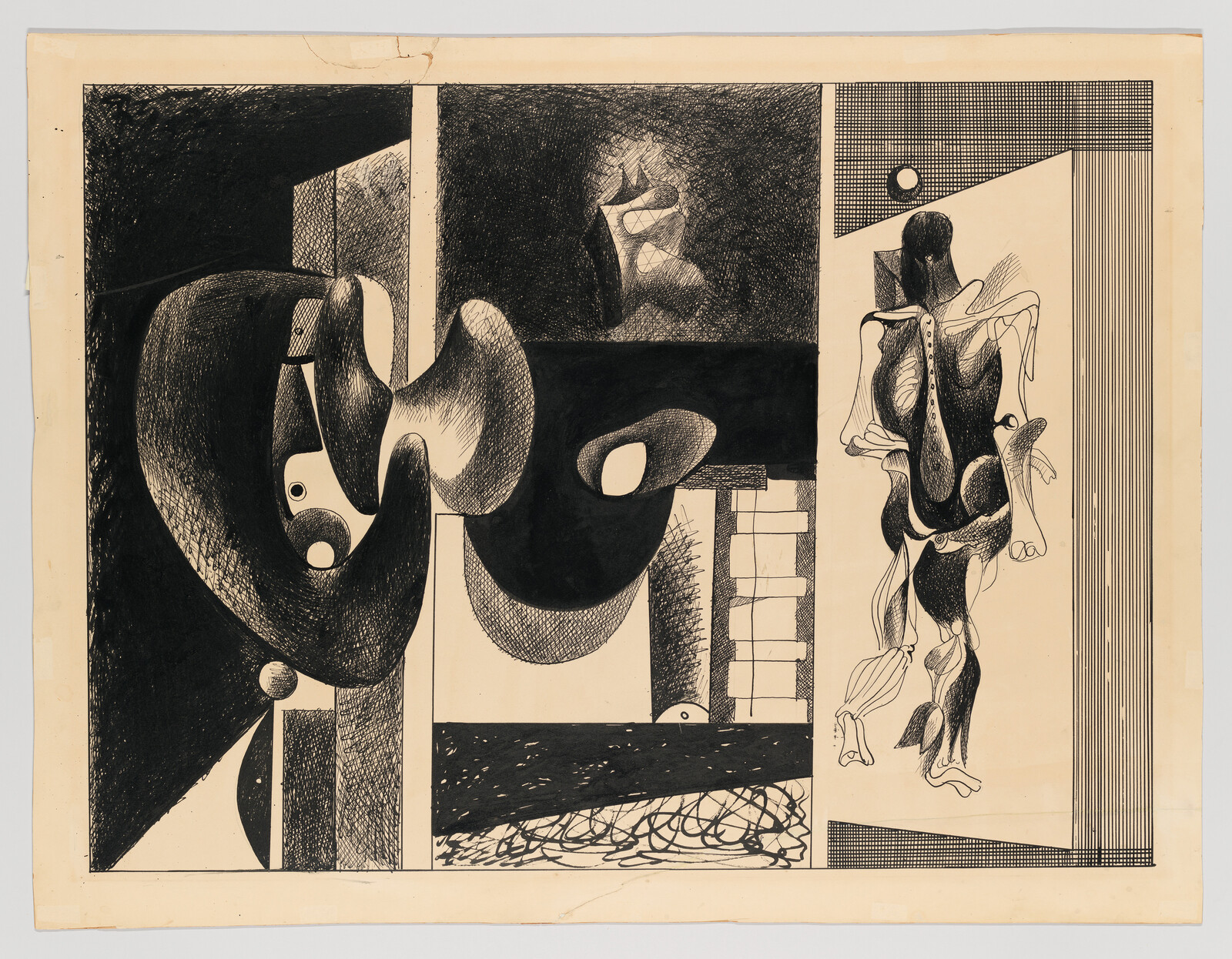

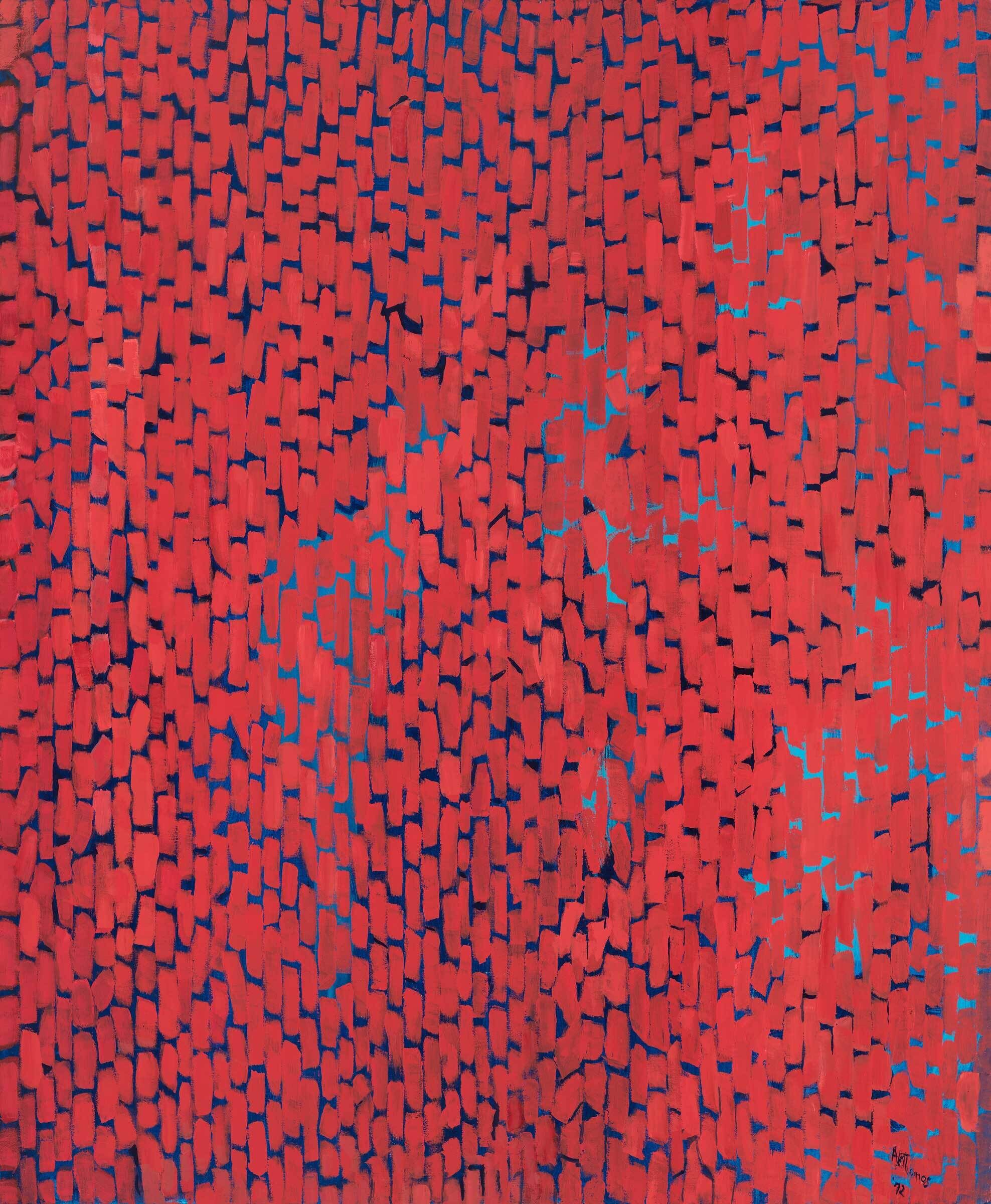

Arshile Gorky played a central role in the shift of American art toward abstraction in the years leading up to the mid-twentieth century. Gorky (born Vosdanig Adoian) immigrated to the United States in 1920, having fled his native country in the wake of the genocide of Armenians by the Ottoman Turks. Among his first major mature works, The Artist and His Mother was one of two canvases based on a 1912 photograph of Gorky with his mother, who never recovered after being sent on a death march in 1915 with her two children. When he rediscovered the photograph, the artist created a subdued meditation on loss and trauma that he would rework intermittently over the course of a decade. Rather than mimic the realism of his source, Gorky pared down his composition to a series of loosely brushed passages that presage the abstract path of his later art. The masklike faces of the two figures, their stark gazes, and the unfinished quality of areas such as the hands instill the image with a haunting inaccessibility—a formal analogy, perhaps, for memory itself.

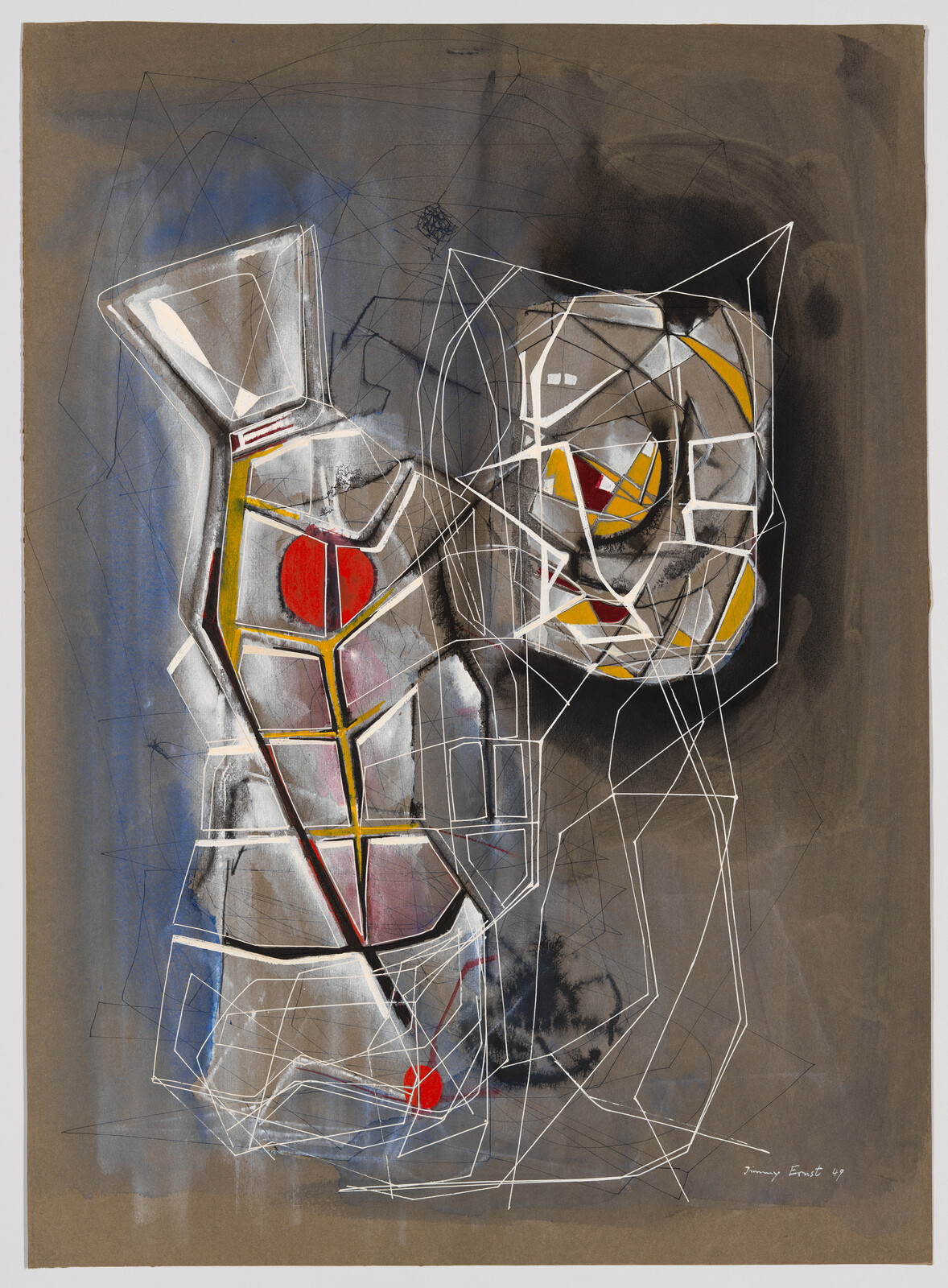

In the 1940s Gorky transitioned to an abstract style that fused the fractured compositions of Cubism with the biomorphic vocabulary of Surrealism. His high-key palette, organic forms, and gestural brushwork would prove formative to the emergence of Abstract Expressionism at the decade’s end. The Betrothal, II was painted a year before Gorky, beset by a string of personal tragedies, committed suicide. The painting’s sinuous forms and lyrical rhythms suggest the themes of union and fecundity evoked by the work’s title, and scholars have pointed to works by Marcel Duchamp (specifically, Bride [1912]) and the early Renaissance painter Paolo Uccello as sources.