David Hammons

1943–

One of the most influential artists living and working in the United States, David Hammons makes art across mediums using strategies of refusal, humor, and provocation. Often centering his own experience as a Black American, over the past five decades, Hammons has addressed issues of race, class, art history, the legacy of slavery, and the experience of being an outsider. Using symbols and stereotypes in surprising, challenging, and sometimes comical ways, Hammons has long employed a “trickster” stereotype to skewer assumptions. He has at turns engaged with and withdrawn from established ideas of artistic success, making art on his own terms and frequently outside of traditional venues.

Body Prints and Los Angeles

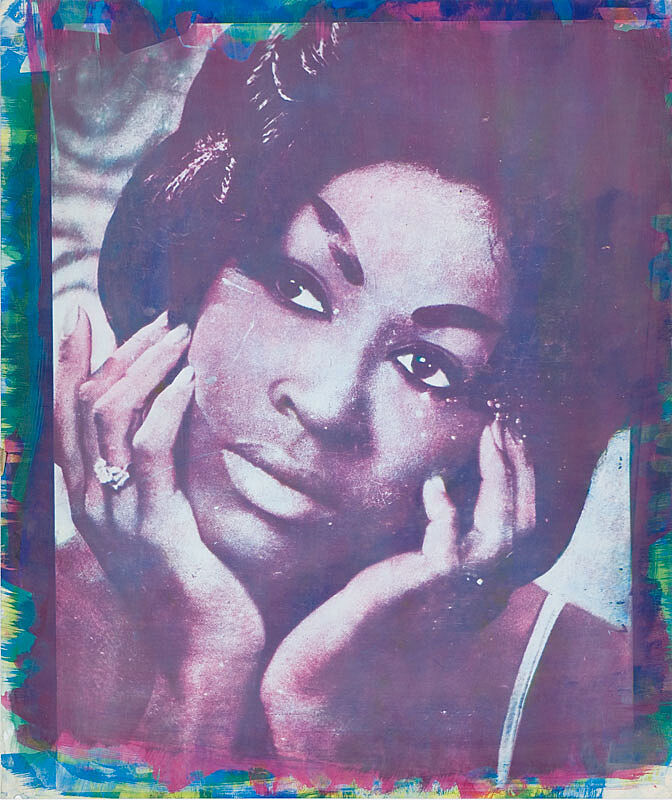

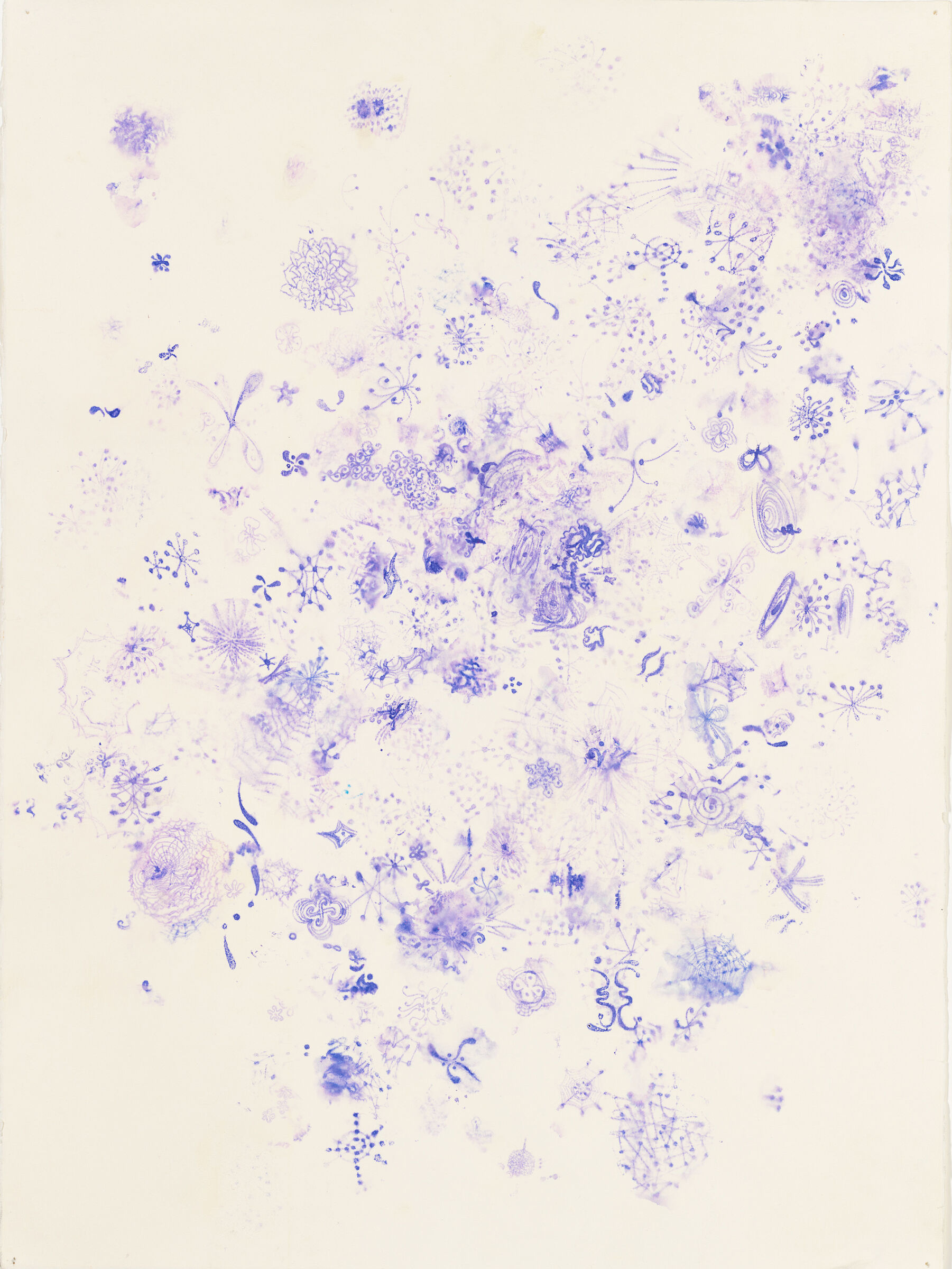

Hammons moved from Illinois to Los Angeles in 1963 to study art, initially enrolling at the Otis Art Institute to study with artist and activist Charles White, who is known for his dignified realist portraits of Black Americans. Hammons took courses at various area art schools and eventually graduated from Chouinard Art Institute (now known as CalArts) in 1968. While Hammons lived in Los Angeles, the city and nation reckoned with the growing Black Power Movement and the turmoil caused by a national heritage of racism, including the assassination of Malcolm X and the Watts riots. Among Hammons’s contemporaries in Los Angeles were Senga Nengudi, John Outterbridge, Noah Purifoy, Betye Saar, and other members of the overtly political Black Arts Movement. In the late 1960s Hammons began what is perhaps his best-known series, the Body Prints, which he created through a performative action of coating his body with grease and imprinting himself onto a piece of paper. He would then sprinkle powdered pigment onto the work, resulting in an intricately detailed mirroring of his body in iconic poses, often sarcastically confronting racial stereotypes.

“Art becomes just one of the objects that’s in the path of your everyday existence” Interview with David Hammons, 1986

In 1974 Hammons relocated to New York City, where he increasingly shifted his focus away from traditional forms of artmaking. He equally incorporated performance, found materials, ephemerality, and public city life—particularly Black city life—into his projects. Based in Harlem, Hammons worked throughout the city and country, creating often challenging and uncanny works, including the incendiary How Ya Like Me Now? (1988), a public billboard featuring a blue-eyed, blond-haired Jesse Jackson, and the strangely poetic Untitled (1992), a sculpture made out of the sweepings from Black barbershops. He used public venues—either reclaimed or formally sanctioned—consistently in his work from the 1980s onward to question the increasing privatization of public space throughout the city, and laid bare power structures inherent in the urban grid. Elusive actions such as Bliz-aard Ball Sale (1983), where Hammons sold snowballs on a Downtown Manhattan street, were sparsely documented yet have taken on mythic proportions in ensuing years. He enacted Guerilla-style interventions like Pissed Off and Shoe Tree (both 1981), where he urinated on and threw shoes over the top of Richard Serra’s sculpture TWU (1981) in TriBeCa, and also participated in projects like the Public Art Fund’s Higher Goals (1987), an installation of impossibly tall bottle-cap-covered basketball hoops in Brooklyn’s Cadman Plaza Park.

Absence as strategy, and Day’s End

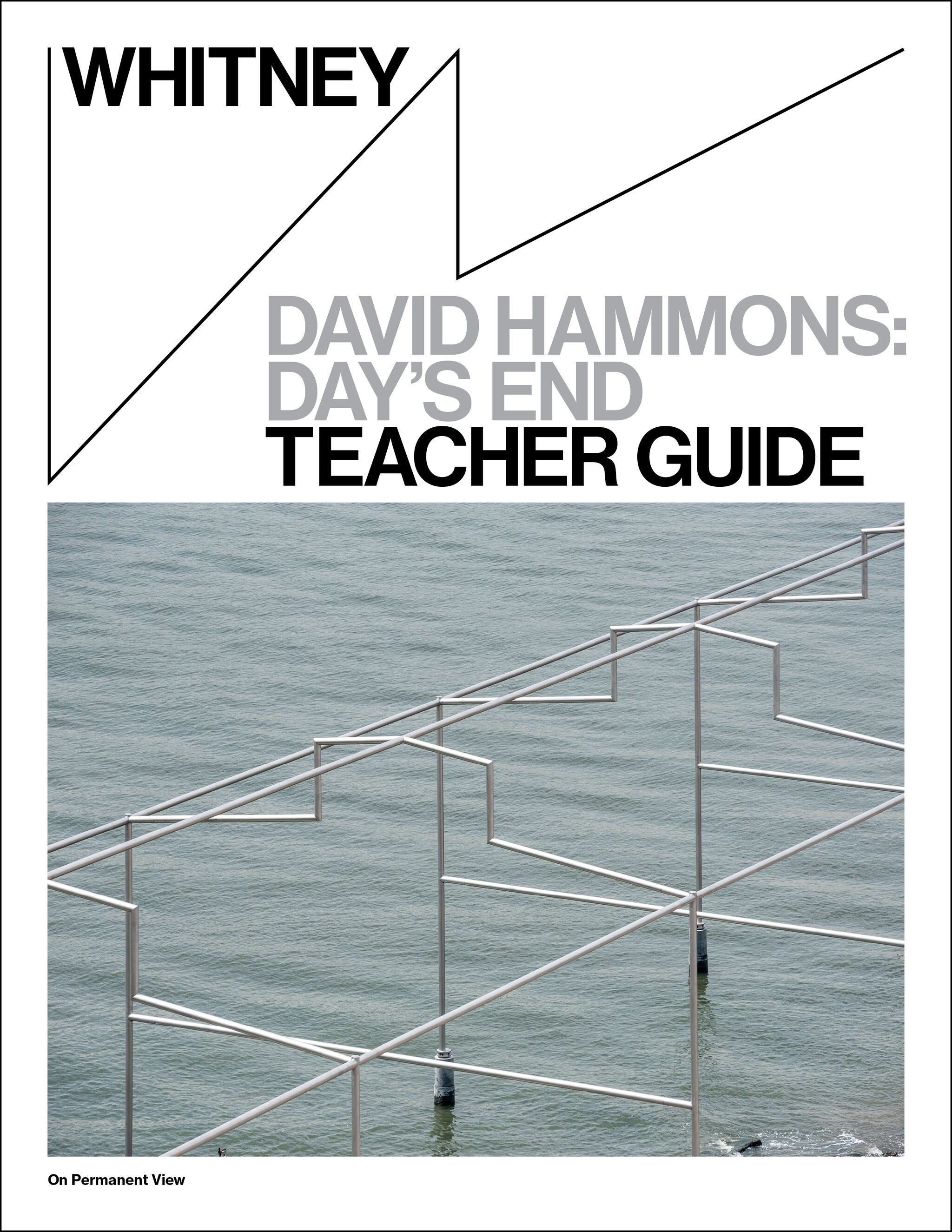

Hammons’s 2002 Ace Gallery exhibition, Concerto in Black and Blue, used the poetics of empty space to stage an interactive performative experience. For this show—his first in almost a decade—he turned off all the lights in an empty gallery, leaving visitors to explore the pitch-black void with handheld blue flashlights. Despite exhibiting infrequently, his works, projects, exhibitions, and public monuments loom large in twenty-first-century art, questioning the public and personal selves, problematizing the idea of America, and using the past to inform the present. In 2014, Hammons visited the construction site of the Whitney’s downtown location and spent much of his time contemplating the waterfront, formerly home to many pier sheds originally used for the transportation industry and later repurposed by queer and artistic communities before being torn down. He subsequently sent the Museum a sketch for a monument to Gordon Matta-Clark, which pays homage to Matta-Clark’s Day’s End (1975), perhaps his most iconic building cut, originally located on the Gansevoort Street pier. The Hammons work, also titled Day’s End, was completed in 2021 and is now on permanent view. This public work just across from the Museum literally frames the waterfront’s history, obliquely referencing marginalized communities that used the site in new and often radical ways, and creates a new space for possibility, contemplation, and inspiration.

Introduction

David Hammons (born July 24, 1943) is an American artist, best known for his works in and around New York City and Los Angeles during the 1970s and 1980s.

Wikidata identifier

Q320846

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed March 3, 2026.

Introduction

Noted for works called "body prints," which entailed the artist smearing his own body—and sometimes his clothes and hair—with a grease such as margarine, pressing himself against board or paper, and then setting the grease with a dusting of pigment.

Country of birth

United States

Roles

Artist, installation artist, multidisciplinary artist, performance artist, sculptor, video artist

ULAN identifier

500114717

Names

David Hammons

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License. Accessed March 3, 2026.