With Uncertainty: Drawing and Change

As a young artist in New York in the 1980s, Jim Hodges struggled to find the register of his voice in painting. “I could mimic stylistically a number of art historical references,” he remembers, “but I was not able to find a way to my ‘self’ through the material.Jim Hodges quoted in Olga Viso, “The Eros of the Everyday,” in Jim Hodges: Give More Than You Take, ed. Jeffrey Grove and Olga Viso (Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2013), 114. Following quote from the same source. Feeling stuck, he set aside his canvases and turned instead to a beloved medium: drawing. This shift in materials—from paint to charcoal and paper—was a pivotal moment for Hodges, upending what he thought it meant to be an artist: “This turn initiated what I now call my ‘practice’ and started me on my way.”

Drawing was Hodges’s first introduction to making art. Growing up in Spokane, Washington, he would draw at the kitchen table while his mother worked around him. She sometimes stepped in to help him with particularly tricky parts of his drawings, once lending a hand when he struggled to copy the cartoon character Wilma Flintstone: “I remember her drawing the lips so beautifully on the smudged page that I’d erased dozens of times in total frustration,” Hodges recalls. “Her thin-lined, easy rendering floated on top of that grey under-layer of mistakes buried below.”Jim Hodges, “Jane M. Saks in conversation with Jim Hodges,” in Jim Hodges, ed. Jane M. Saks, Robert Hobbs, and Julie Ault (New York: Phaidon Press, 2021), 6. Coaxing an image out of the blank space of the page, watching as each new line appears, and wondering how the marks will resolve themselves into a recognizable form—this is part of the magic of drawing.

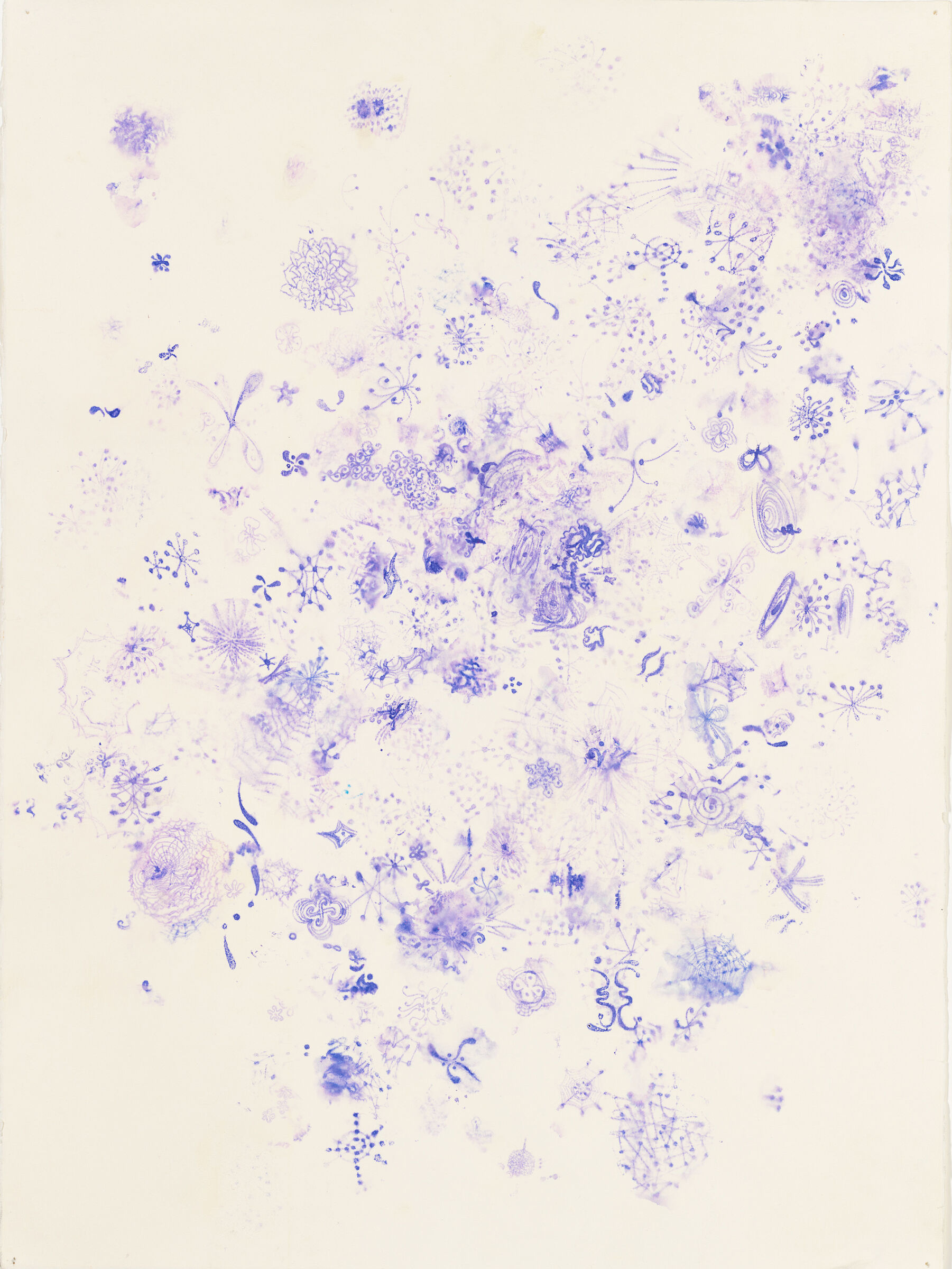

The art historian Catherine de Zegher refers to the gradual reveal of drawing as an “unfolding.”Catherine de Zegher, “A Century under the Sign of Line: Drawing and Its Extension (1910–2010),” in On Line: Drawing Through the Twentieth Century, ed. Catherine de Zegher and Cornelia Butler (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2010), 23. Following quote from the same source. As she describes it, drawings emerge out of a process of becoming: “mark becoming line, line becoming contour, contour becoming image.” A degree of uncertainty, and anticipation for what is to come, is inherent to the practice. To look at the act of drawing in this way—as something unfurling, generative, undetermined—is to see it as a medium charged with the promise of possibility; or, as the curators Claire Gilman and Roger Malbert suggest, drawing “upholds . . . a willingness to imagine that things might be otherwise.”Claire Gilman and Roger Malbert, Drawing in the Present Tense (London: Thames & Hudson, 2023), 8.

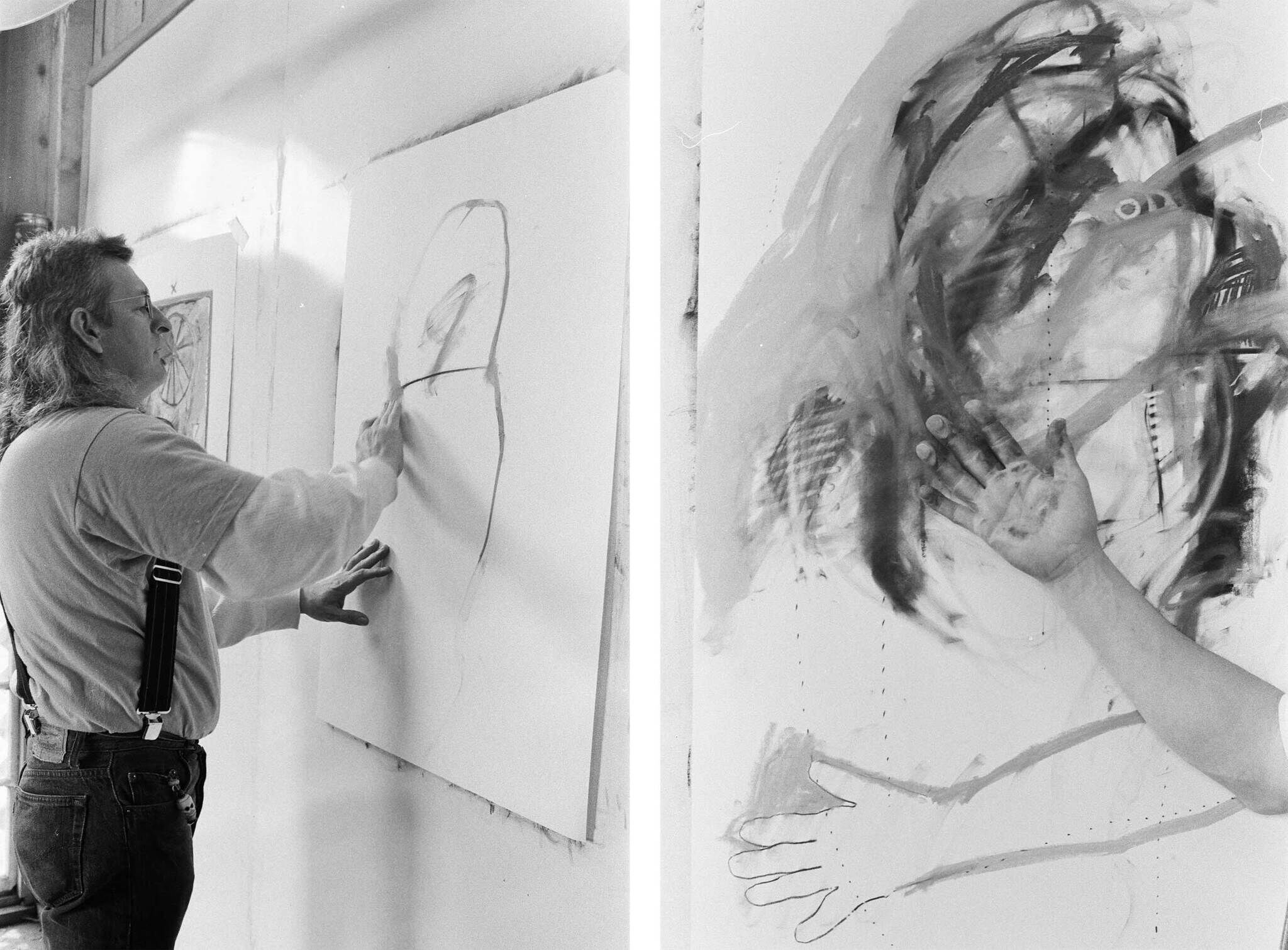

For Wiyot artist Rick Bartow, drawing offered a way to chart a path through darkness. “When I returned from Vietnam, like so many others, I was a bit twisted,” he reflected. “I was a house filled with irrational fears, beliefs, and symbols.”Rick Bartow, artist statement, “Transformations, 1989,” Froelick Gallery, Portland, OR, 1. Following quote from the same source. Drawing had always been an irresistible impulse for Bartow, but, by the late 1970s, it had also become an act of catharsis. Working on sheets of paper taped to his studio wall, he began his drawings with a few spontaneous marks made with pastel crayon or a handful of pastel dust applied to the page with the flat of his palm. Images gradually emerged from these improvisational gestures—animals and humans whose features melded together—as he built up layers of color or worked back down to the paper with erasers, a method he likened to the experience of personal gain and loss. Out of this balance of additive and subtractive mark making came his “transformational” drawings, in which he attempted “to exorcise the demons that had made me strange to myself.”

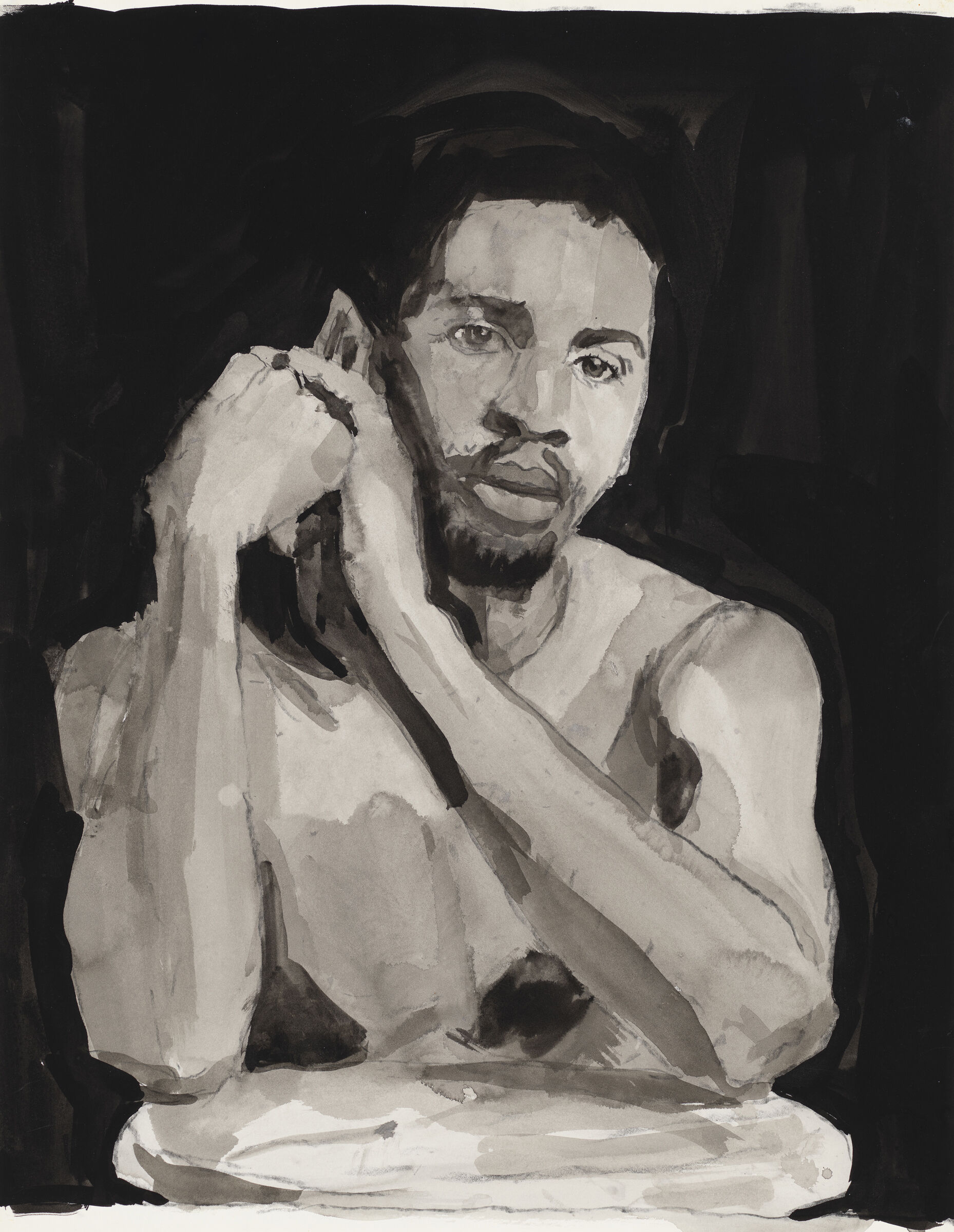

Exorcism might also have been the motivation behind Darrel Ellis’s Self-Portrait after photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe (1989). The original photograph elicited a strange tangle of feelings in Ellis. “I struggle to resist the frozen images of myself,” he wrote. “They haunt me.”Darrel Ellis, artist statement, in Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing (New York: Artists Space, 1989), 20. It is unclear what exactly haunted him. Was it the photographer? The memory of being photographed? Or the version of himself he saw in the image? Whatever it was, he chose to engage with it directly, translating the crisp atmosphere of the studio portrait into a brushed ink drawing. In the resulting self-portrait, blooms of gray wash become shadows on his skin and strokes of velvety black make up the background. But if drawing can be a process of release, of letting go, then its intimate nature—hand and fingers brushing the page as the drawing implement moves across it—also offers a means of getting closer. Another hand-drawn photographic intervention, Wendy Red Star’s series 1880 Crow Peace Delegation (2014) came out of the artist’s intensive research into formal portraits of late-nineteenth-century Apsáalooke (Crow) leaders, which had been preserved in archives where little about the subjects’ identities was recorded. In a gesture of reverse erasure, Red Star modified copies of the images with red marker, inscribing them with biographical details from each man's life. The act of outlining the sitters’ garments, carefully tracing the intricate contours of buttons, rings, and narrow strips of ermine, was a way for Red Star to focus her attention and connect with these historic figures and her own Apsáalooke heritage.

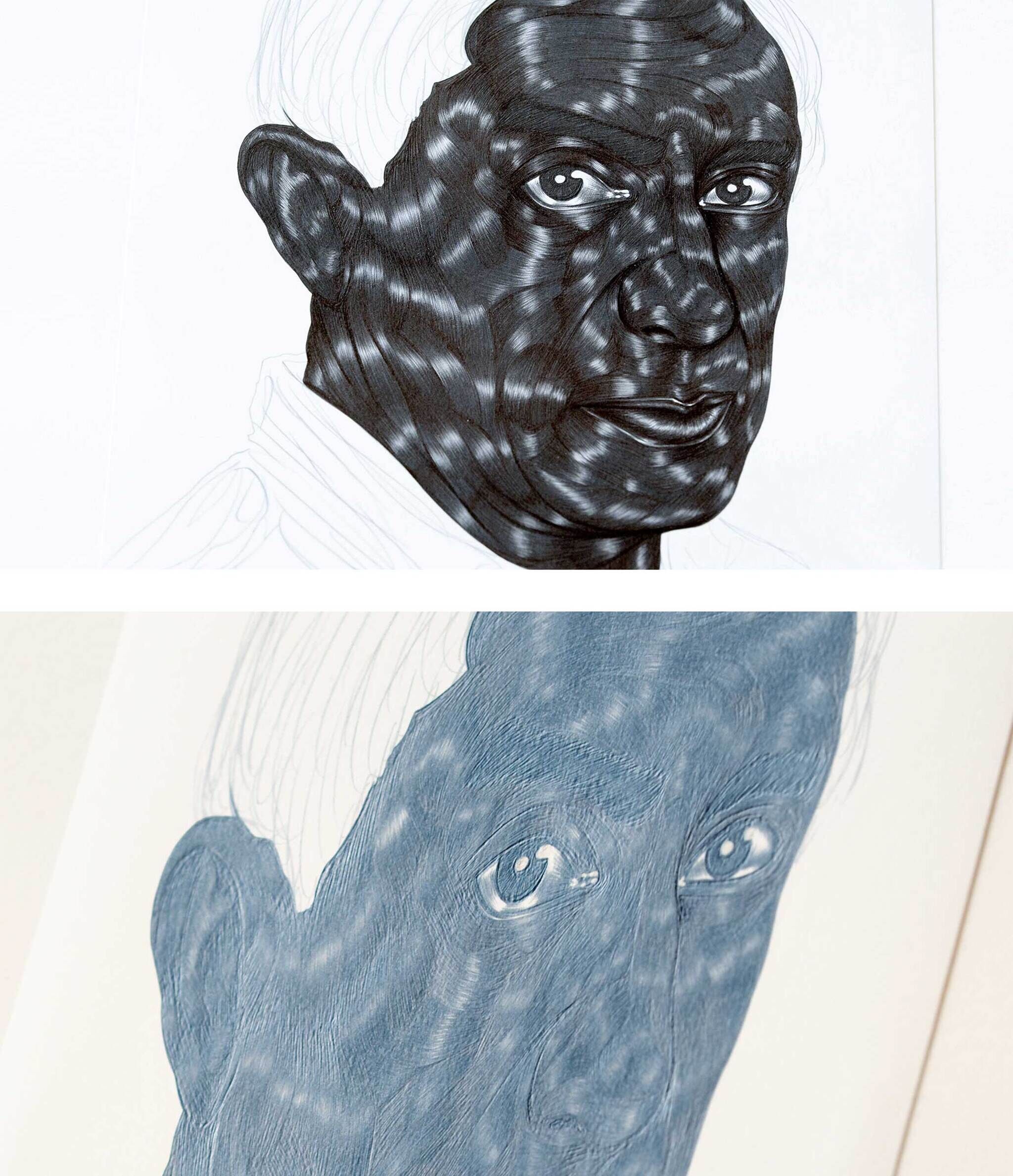

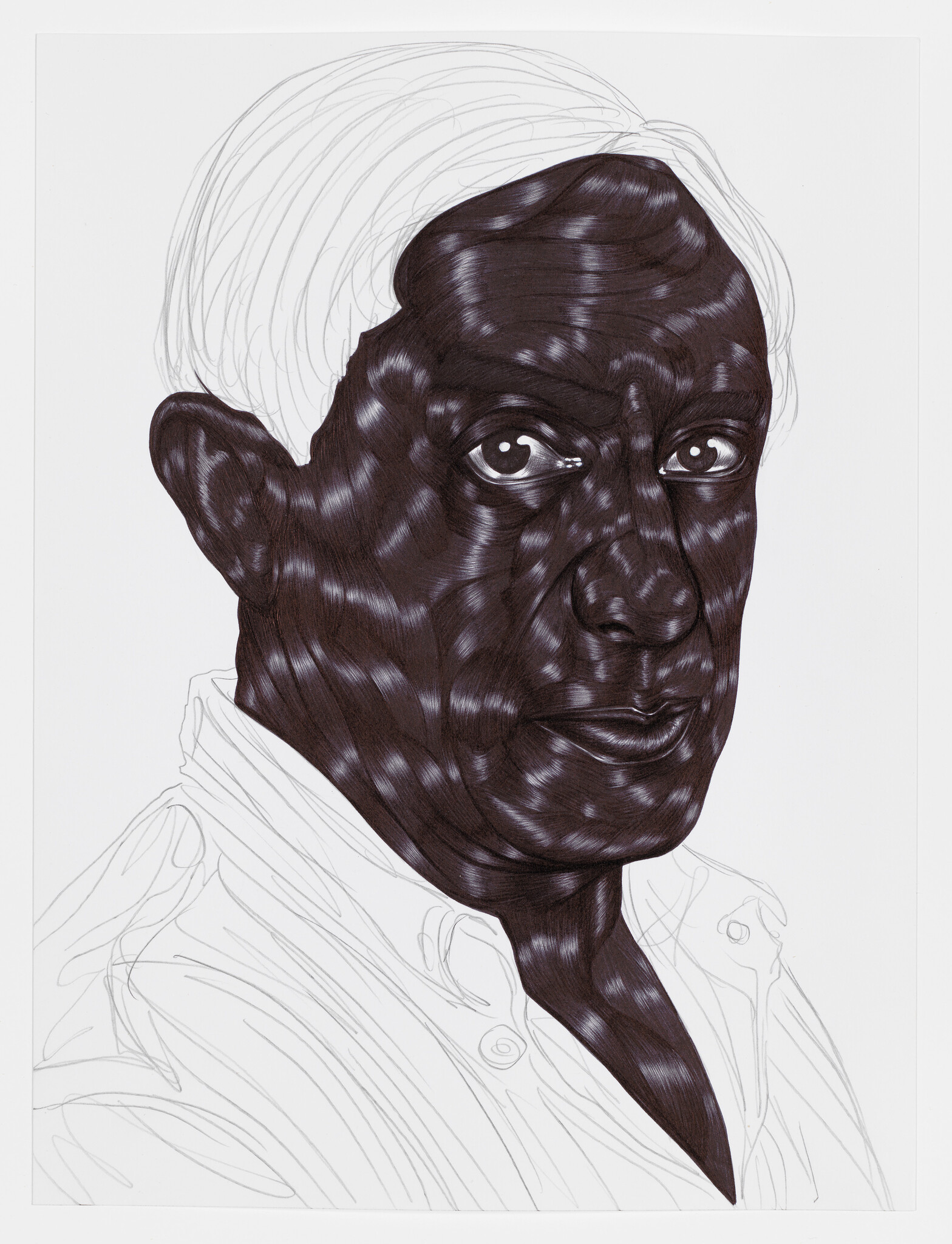

In Toyin Ojih Odutola’s portraits, Black identity is revealed as something fluid, malleable—as difficult to pin down as a bead of mercury. In works like The Treatment 20 (2015), she achieves a sense of flickering movement with ballpoint pen, applying lines of black ink in passages so dense they begin to read as metallic, changing color when they catch light. This effect—often referred to as sheen—is likely due to the oil-based nature of ballpoint pen ink. “The sheen is the key,” Ojih Odutola explains. “When I press the pen into the surface of paper . . . a sort of engraving is taking place, akin to the process of printmaking. The magic of viscous fluid is that the darkest areas, the relief-like marks, also become the lightest areas by simply changing one’s point of view. Light and shadow play are what make the pen and ink interactive.”Toyin Ojih Odutola quoted in Ashley Stull, “Toyin Ojih Odutola,” BOMB, February 9, 2015, https://bombmagazine.org/articles/toyin-ojih-odutola/.This technique allows her to represent skin as a shifting, sinewy landscape—something constantly in flux—on a static sheet of paper.

Like Ojih Odutola, Blythe Bohnen perceived a link between drawing and identity formation, the latter of which she described as an ever-evolving understanding of her self: “As soon as I have a clear sense of who I am,” she observed, “something occurs which doesn’t fit, and I have to work to reestablish a new sense, incorporating that new information.”Blythe Bohnen, interview by Gail Livingston, undated, transcript, David Hall Gallery, Wellesley, MA, 7. Following quotes from the same source, 2, 6. She felt a similar process of reassessment when she drew, with every new mark introducing a change. Draw a straight line across a blank sheet of paper, and a horizon line is created, or a partition. Add another line and pictorial depth or compositional balance emerges. “Each added mark shifts everything into new relationships,” she explained, all produced by the simple motion of dragging graphite or ink across paper.

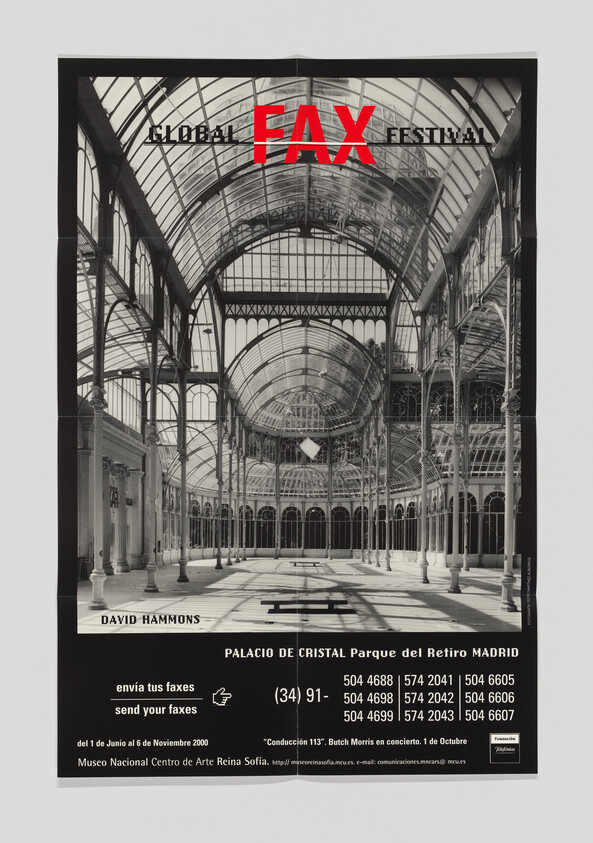

Always interested in the connection between physical gesture and recorded line, Bohnen found that she herself could become an instrument for drawing in her series Self-Portrait: Studies in Motion, the result of a chance discovery while experimenting with long-exposure photography: “An accidental movement created a line from my eyes. Bang. I could do that on purpose! Instead of using paint or graphite I could use my body.” Like Bohnen, many of the artists included in What It Becomes integrate their bodies directly into the act of mark making: David Hammons pressing himself to a sheet of paper; Maren Hassinger drawing directly on her face; Naotaka Hiro and Ana Mendieta tracing their contours. Hands becoming stamps, eyes inscribing lines, skin serving as support. What are the implications of introducing one’s body so directly into the drawing process?

For Catherine Opie, the decision to have a drawing etched into her back in Self-Portrait/Cutting (1993) was a matter of embodying her queer identity. In this iconic photograph, she faces away from the camera, showing us instead her bare back. Carved into her skin is a scene a child might have drawn—two stick figures holding hands, the sun nestled behind a friendly cumulus cloud, and, in the distance, a house with a plume of smoke blowing like a scarf caught in the wind. At the time, this simple line drawing symbolized Opie’s desire for a domestic partnership; the decision to have it cut into her skin—set against the backdrop of the early nineties and the fight for gay marriage, the stigma around S/M practices, and the immense loss of life caused by the AIDS epidemic—was an unapologetic proclamation of who she was.

While Opie’s photograph addresses personal grief and yearning, the support of her community was essential to the work’s creation. Video documentation of the process reveals that several of Opie’s friends assisted her in the making of this self-portrait. The cutting was done by fellow artist Judie Bamber, who had no experience with a blade. This was an intentional choice on Opie’s part; rather than a perfect cutting executed with confidence, she wanted a sense of apprehension and imprecision in the marks—much like a child’s drawing—and that tentativeness comes through in the varied pressure of Bamber’s lines. In the video, Bamber gradually grows more assured as she traces the design into Opie’s back, but she is nervous and hesitant as she makes her first test marks. Her trepidation is understandable—this is a drawing that has physical consequences, and both the drawer and sitter are made vulnerable.

Introducing the body into the drawing process in such a direct way raises additional considerations around the concept of vulnerability, a term often used by conservators when discussing works on paper. Paper is susceptible to damage due to its fragile nature: inks can be light sensitive and prone to fading, chalky pastels can shift when moved, and charcoal can be lifted back off the page with the touch of an eraser. The longevity and fragility of drawings is described with words like unstable, fugitive, insecure, and loss. There is a reminder embedded in these terms, and in the materials themselves, of impermanence and potential degradation. A drawing may record and preserve a moment—a gesture on the page—but the record itself is susceptible to change over time.

If the works presented in What It Becomes remind us of the unavoidable nature of existence—that things will inevitably change—they also offer us the promise that things can change. These works express, each in their own way, a kind of searching or yearning played out through mark making, but they also convey a degree of comfort with uncertainty, a delight in the possibilities of moving through an ever-shifting world. For Hodges, moments of transition have always gone hand in hand with the process of drawing. Drawing reoriented him as a young artist struggling to find his way, and it is a medium he continues to return to during periods of upheaval and growth: “I have been through a process of shedding skins, breaking through boundaries—imposed, self-imposed, learned, whatever,” he explains. “And the funny thing is, there’s always another wall that I go crashing into, another layer of crap to shed, another blossom that reveals more complexity and challenges. Thankfully this process doesn’t stop.”Jim Hodges quoted in Viso, “The Eros of the Everyday,” 115.