Day's End

Artists Among Us

Our inaugural season considers the American artist David Hammons and his new sculpture, Day’s End (2014–21). This is a monumental, permanent public installation that pays tribute to a long-destroyed 1975 artwork of the same name by the artist Gordon Matta-Clark. Anchored on the banks of Manhattan’s West Side and stretching into the Hudson River, Hammons’s Day’s End is sited next to the Museum and occupies the precise location where Matta-Clark’s work once stood. We follow the evolution of the Manhattan coastline through the history of the Meatpacking District, and celebrate the communities that have shaped the neighborhood where the Whitney now stands.

Hosted by Carrie Mae Weems.

This Is Artists Among Us: Day’s End

Season 1 Trailer

The Whitney Museum of American Art presents Artists Among Us, a podcast about American art and culture. In keeping with the Whitney’s mission, collection, and programming, Artists Among Us considers the complexities and contradictions that have shaped the United States we experience today.

Released May 3, 2021

In order of appearance: Kellie Jones, Glenn Ligon, Curtis Zunigha, John Jobaggy, Efrain Gonzalez, Catherine Seavitt

0:00

Trailer - This Is Artists Among Us: Day's End

0:00

Kellie Jones: Hammons makes us think about what was there, not just last week, not just ten years ago, but generations ago, before New York.

Carrie Mae Weems: In the Hudson River, on the West side of Manhattan, resides a new, permanent sculpture. It’s called Day’s End, and it’s by the artist David Hammons. Day’s End is a nod to another sculpture, by the same name, that was on this very same spot, forty-five years earlier.

Glenn Ligon: He's creating something that nobody would think David Hammons would create. It's about something that's kind of ghostly, that exists and does not exist at the same time, that riffs on something that riffs on something else.

Carrie Mae Weems: Welcome to Artists Among Us, a podcast from the Whitney Museum of American Art that reimagines American art and history. I am Carrie Mae Weems. And in this season, we’ll be looking at the history of this ever-changing location, inspired by Day’s End.

We’ll look at the Indigenous people that lived here,

Curtis Zunigha: Some of the stories that I share about our history have to start with creation and lifeways that went on for several thousands of years on this very land.

Carrie Mae Weems: To the people who worked here later,

John Jobaggy: These were farm kids who came to America—poor kids, like my grandfather—to make a better living for themselves. They weren't coming to New York to be meat packers, to be butchers.

Carrie Mae Weems: To the underground communities that made it their home,

Efrain Gonzalez: If you come from a place where your sexuality doesn’t exist, if you come from a place where your sexuality is considered abnormal and evil, you come here, and you find out it’s perfectly normal, it’s ordinary.

Carrie Mae Weems: Please join us as we explore this fascinating and complex view of the city as it’s framed by Day’s End.

Catherine Seavitt: I think the sculpture offers this opportunity to capture the imagination and to kind of burn its way into the brain like those other things that are gone.

Carrie Mae Weems: Artists Among Us drops in the Spring. You’ll find it everywhere you get your podcasts.

Trailer - This Is Artists Among Us: Day's End

The Dawn of Day’s End

Episode 1

“David’s work isn’t always about what you see or even what you notice. Often, it’s about what’s invisible but right in front of you.”

— Carrie Mae Weems

Our inaugural episode introduces David Hammons’s Day’s End (2014–21). As we discuss the project’s origins and site-specific nature, the layered social and cultural histories of the site begin to unfold.

Released May 14, 2021

In order of appearance: Bill T. Jones, Glenn Ligon, Adam Weinberg, Tom Finkelpearl, Kellie Jones, Luc Sante, Guy Nordenson, Catherine Seavitt, Betsy Sussler

Gordon Matta-Clark, Days End Pier 52.1 (Documentation of the action "Day's End" made in 1975 in New York, United States), 1975, printed 1977. Gelatin silver print, sheet: 8 × 10 in. (20.3 × 25.4 cm) Image: 7 9/16 × 9 7/16 in. (19.2 × 24 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Harold Berg 2017.132. © Estate of Gordon Matta-Clark / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

David Hammons, Day's End, 2014. Graphite on paper, sheet: 8 1/2 × 11 in. (21.6 × 27.9 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of the artist 2021.11

Dawoud Bey, David Hammons, Bliz-aard Ball Sale I, 1983, printed 2019. Inkjet print mounted on Dibond, sheet: 33 × 44 in. (83.8 × 111.8 cm) Image: 40 1/16 × 29 3/16 in. (101.8 × 74.1 cm) Mount: 33 × 44 × 1/8 in. (83.8 × 111.8 × 0.3 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; purchase, with funds from the Jack E. Chachkes Endowed Purchase Fund 2020.31. © Dawoud Bey

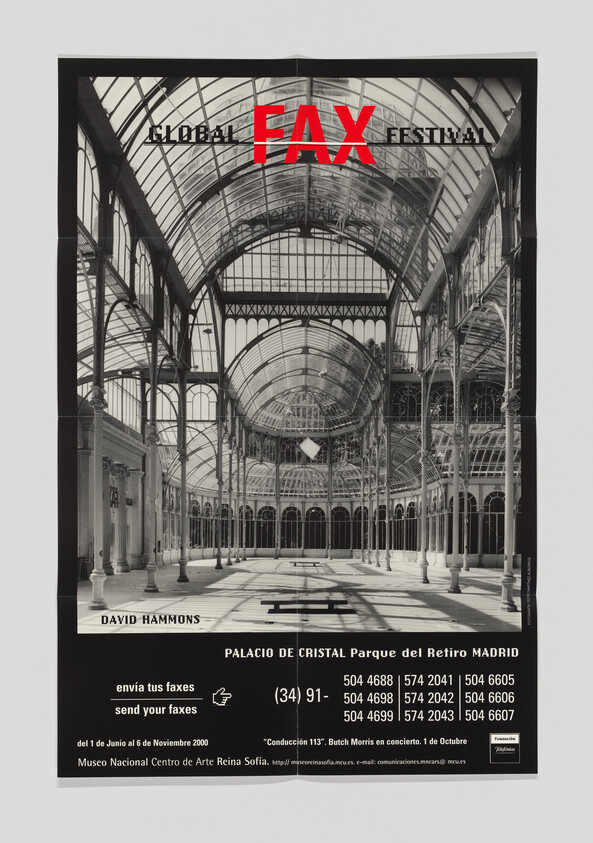

David Hammons: Rousing the Rubble, 1969–1990. Exhibition website, MoMA PS1, New York (Dec. 16, 1990–Feb. 10, 1991).

David Hammons: Higher Goals. Exhibition website, Public Art Fund.

Randy Kenny. "Making Doors: Linda Goode Bryant in Conversation with Senga Nengudi." Ursula 1 (2018).

Max Lakin. "When Dawoud Bey Met David Hammons." New York Times, May 1, 2019.

"Episode 360: Dawoud Bey." Bad at Sports. Podcast audio, July 23, 2013.

0:00

Episode 1 - The Dawn of Day’s End

0:00

Carrie Mae Weems: In 1975, an artist determined to make something new went to a warehouse building on Pier 52 on the Hudson River in the Meatpacking District. That artist was Gordon Matta-Clark.

He went in with a ladder and chain saw and cut a trench into the floor of the warehouse. He also carved a massive new-moon shape into the building’s end wall. This flooded the space with light, resulting in a work of art unlike any other. Gordon called it Day’s End.

At the time, the piers were a gathering place for the queer community of New York, and images of the time show men sunbathing naked, reading books, having sex there. Historically, the piers had been a place of commerce. Now they were on the brink of collapse, waiting for a bankrupt city to demolish them. And within a few years, many of them were torn down, including Pier 52, and Day’s End disappeared.

By 2015—four decades later—just like everything else around it, the Meatpacking District had changed dramatically. Surprisingly, it now had even a new museum: the Whitney Museum of American Art. As the Whitney was putting the finishing touches on its own new building, the artist David Hammons came for a visit. Talking with Adam Weinberg, the Museum’s Director, David was looking out the window as Adam pointed out the spot where Day’s End once stood. A few days later, a sketch arrived in the mail, a simple outline of the building that once stood there, at Pier 52.

That small, simple, elegant sketch has been turned into a massive but delicate sculpture by David Hammons. It emerges out of the Hudson, on the very spot where the original Day’s End once stood, and it’s also called Day’s End.

Bill T. Jones: I think he's a champion for something about what I call the world of ideas. I have been known to say artmaking is participation in the world of ideas. Or art does for me what religion traditionally did. It organizes a seemingly chaotic universe.

Glenn Ligon: He's creating something that nobody would think David Hammons would create. But still, it's so much about David's work because it's about this kind of ephemerality. It's about something that's kind of ghostly, that exists and does not exist at the same time, that riffs on something that riffs on something else, a pier that was here that's not here anymore.

Carrie Mae Weems: Choreographer Bill T. Jones and artist Glenn Ligon have long admired David’s work.

Adam Weinberg: It's a building without doors, without windows, without walls, without ceiling, without floor.

Carrie Mae Weems: Whitney Museum Director Adam Weinberg.

Adam Weinberg: So it's not a building. It's sort of like a drawing because it's a drawing in space, but yet, it's not physically a drawing. It's a sculpture. And I see it also as a container that contains nothing and a container that contains everything. It's . . . you look through it, you see the city, you see the water, you see the light, you see the air.

Carrie Mae Weems: What you don’t see—at least not immediately—is history. But the place where Day’s End now stands has a varied and rich history that, together, we’ll explore.

I’d like to welcome you to Artists Among Us, a podcast from the Whitney Museum of American Art that reimagines American art and history. I’m Carrie Mae Weems, an artist, and over the years, I’ve given a great deal of thought to history and the way in which art can make the invisible visible. I’m also a great admirer of David Hammons. And I’m looking forward to exploring the fascinating ways that his sculpture invites us to reflect on the past of this site—who lived there, who worked there, and then, how it all changed.

If you haven’t heard David’s name before, that’s probably at least in part because he wants it that way. He prefers speaking more through his work than through his words. But his work has a lot to say about social conditions and the structures that constrain us. At the same time, the work is imbued with a profound sense of spirit, magic, and wonder.

David’s work isn’t always about what you see or even what you notice. Often, it’s about what’s invisible but right in front of you.

Tom Finkelpearl: One time, David called me up, and he said, “I’ve done a project at 14th Street Subway Station. Just go over there. You’re going to figure out what it is.”

Carrie Mae Weems: Tom Finkelpearl curated an exhibition of David’s work at PS1 in Queens in 1990.

Tom Finkelpearl: And so, I went there, and I walked through. It was a construction site. And I looked, and I said, "Oh, this is it," this kind of weird shack. And then I was like, "Enh?" And then I walked all the way to the end of the platform, and there was this stack of metal garbage cans, perfectly stacked, and that was it.

And so, I called David back afterwards, and I said, "That was it, right?" And he said, "Of course, that was it," right? And it wasn't . . . he hadn't done anything. He had just sort of intervened in the city, to get people to go to the place and look at this thing.

Glenn Ligon: David's made work out of helium balloons. David's made work by putting a fax machine in the gallery. David's sold snowballs on the street. David makes paintings. David makes sculptures. David makes interventions and books.

Carrie Mae Weems: Again, Glenn Ligon.

Glenn Ligon: All of that gives you this possibility that anything you think of fits into one's practice. So I often say that I'm a painter. But really, what I want to do is make lots of different kinds of things. And David is kind of the artist that gives me a kind of permission to do that.

Carrie Mae Weems: The permission that Glenn is talking about is not only important to us makers. It’s also important to the viewer. It offers the viewer a chance to see the many different things that can be art. David has been making work publicly for decades. It’s never been about decorating a site. It’s really about engaging the city—sometimes channeling its energy and sometimes resisting it.

Glenn Ligon: I lived in downtown Brooklyn, I think in the mid-eighties. And I lived near the big post office in downtown Brooklyn. And for weeks on end, I would see this guy out in the park in front of that post office nailing bottle caps onto this giant telephone pole. And I just thought, "What is this?" And then when the giant telephone pole was stood up, I realized, oh, it's an artwork. And that guy was David Hammons, and he was making this piece I think called Higher Goals.

In Higher Goals, Hammons transformed forty-foot telephone poles into basketball hoops, making the nets impossibly high and out of reach.

Glenn Ligon: In retrospect, I think what was amazing about that is he did it outside. He didn't do it in the studio and then bring it somewhere. It was important for him to do it on-site, and that's what he did.

And so that kind of idea that you make your work in public was quite extraordinary, I think. And it's sort of demystified by seeing that making happen. So literally, I saw him doing stuff on telephone poles in the park, and I didn't think he was an artist. I just thought, this is some crazy guy tapping the tops of beer bottles . . . beer bottle caps into telephone poles for weeks on end. And then it's like, "Oh, art." But I loved that, that line between crazy guy and art was very porous. But also, I think he's one of those artists that really takes his clues from the street, or from the environment.

Kellie Jones: In that time, people were still fighting to be seen, because even some of these so-called alternative spaces in downtown New York were not showing the work of Black people, people of color, et cetera.

Carrie Mae Weems: Making work in the streets meant David could claim the opportunities he saw without waiting for an invitation from a museum or a gallery. He did, of course, have some exhibitions, especially in a gallery called Just Above Midtown. But at the same time, he preferred working in the streets, in places like vacant lots, basketball courts, parks, and on street corners. And as opposed to buying materials, he preferred found objects: gum wrappers, chicken bones, wine bottles, bottle caps, and even snow. David’s move to the street was a critical gesture—a rejection of the mainstream art world and all of its traditions. But beyond that, it also expanded his audience to include anyone who happened to be passing by. One of the beautiful things about David is that he offers the audience the richness of an art experience, whether they know they’re looking at art or not. I think he’s a master. Kellie Jones is an art historian who’s been friends with David since the early eighties.

Kellie Jones: He's using telephone poles and decorating them with patterns made from bottle caps, in '86. But these are also related to something that is really kind of . . . not into street work or types of works, but something called “Bottle Trees” that he does, where he upends bottles, liquor bottles, cheap liquor bottles, that are strewn around in the urban space, and upends them on trees, just in abandoned lots and so on.

You don't have to go to a gallery to see this. It's something unknown, but you look at it, and you say, "What's going on there?" And it makes you stop and think.

Carrie Mae Weems: Hammons once guessed that he spent about eighty-five percent of his time out on the streets. He said, “When I go to the studio, I expect to regurgitate these experiences of the streets, of all the social things I see—the social conditions of racism. It comes out of me like sweat."

Take Higher Goals, the sculpture that Glenn Ligon unwittingly observed Hammons making. With its mosaic of bottle caps, it’s a funky but beautiful, masterful piece. At the same time, the basketball hoops forty feet off the ground suggest futility and frustrated hopes.

David made the work in 1986. That same year, Spike Lee’s character Mars Blackmon debuted his beloved Air Jordans, and Run-DMC rapped an ode to Adidas Superstars. It was a big moment for advertisers hoping to use dreams of basketball stardom to make young Black men into high-end consumers. But David did more than simply critique the situation. With David, nothing is ever really that simple. Instead, Higher Goals both embodies frustrated hopes and offers up a tremendous amount of visual appeal. You didn’t have to choose. You could live with both the good and the bad at the same time.

Kellie Jones: He's always about the kind of . . . the social connection with humanity in these works. So it could be transactional, where you're selling people snowballs, or little baby shoes, which he also did in the eighties.

Carrie Mae Weems: Kellie’s talking about David’s great work Bliz-aard Ball Sale.

Adam Weinberg: It snowed. And in a way, maybe a snowball or a snowman is maybe the first act of sculpture that any kid who grows up in the snow makes. It's the first time you actually fashion something in 3-D. What is the simplest version of that? A ball. So here he is, he's making snowballs.

Carrie Mae Weems: Imagine several dozen balls—snowballs—lying on the ground, arranged in varying sizes from small, medium, and large, laid out on a North African blanket, set up on a street corner in Cooper Square in the East Village. This is where any number of street vendors informally came to sell all kinds of things. And then Hammons once guessed that he was inspired to go there by a man who was selling about thirty sets of false teeth.

Luc Sante: It's one of the great regrets of my life that I did not happen to walk [by], and I walked in front of Cooper Union four times a day for years.

Carrie Mae Weems: Luc Sante is an author and professor who grew up in New York.

Luc Sante: And somehow, I missed the day he was selling snowballs. I'll never forgive myself. But reconfiguring things you're familiar with . . . I mean, he does that.

Kellie Jones: He's fascinated with the evanescent, with the ephemeral . . . and the tension between all of those things. And it's also fun. Part of his work is, like I said, the social engagement. Art doesn't have to be so serious. Let's have fun with it. And people buy a lot of crazy things.

Carrie Mae Weems: Including—and this was probably not beside the point—art.

Kellie Jones: Why not buy a snowball that's perfect, made with a melon baller or whatever you're going to use . . . an ice cream scoop, make [a] perfect snowball? People will spend a buck on that, or whatever, ten dollars, if they have money. So it's also, there's ways that it deals with commerce, the kind of, "I'm going to sell you this and make money on ephemerality, but I'm also going to have fun with this."

Adam Weinberg: So much of his works are found objects. So many of his works are about hiding, about covering, about what I call hiding in plain sight, you know. I mean things that you can see, but you can't see. There're many mirrors in his work, which are about everything and nothing. I mean, you see everything in it, and whatever you're seeing is constantly changing.

Glenn Ligon: Hammons once said the less he does as an artist, the more artist he is. And so that statement, outside of whatever he's made, has been important. I think about that when I'm making my work. What's the least I can do?

Kellie Jones: It's not just the type of objects he makes because he makes all these different things that for all intents and purposes are just like little junky things, frankly: bottles that are discarded, hair that's discarded . . . things that are just found in everyday that you would just not pay attention to. But he understands how those things relate to our social life and being and how we'll recognize that in them, if he does certain things to them. If I was going to say anything about Hammons it is that he really knows humanity, the social human spirit, and is able to reflect that and talk to us through these works in a way that astounds us, amazes us, makes us laugh, makes us just be very thoughtful and meditative. But that he's able to really connect with us on things that are in our everyday life and make them really sing out with something that's just extra special.

Carrie Mae Weems: With its sleek, stainless steel frame, Day’s End may appear to be different from the improvisational work that David made on the streets. But it shares the same spirit that Kellie describes.

So this is the story: David was visiting Adam at the Museum before the Museum opened. They were talking about where Gordon Matta-Clark’s Day’s End once stood.

Adam Weinberg: I noticed he was paying attention to that but didn't think anything about it. And that's, I think, one of the interesting things about David. It's like . . . you might be saying something very casual, and he's taking it a completely different way. And the things that you think you're telling him you think is what he's paying attention to, but actually, he's paying attention to the things that you're not paying attention to.

Carrie Mae Weems: The building that Gordon used to make the original Day’s End was enormous, huge, about the size of a football field. The new-moon shape that he carved into the building’s western wall let in a stream of light, which moved dramatically around the vast warehouse as the sun began to set. This gave the work its name—Day’s End—and its reason for being. When Adam pointed out the site to David on their tour of the new Museum, all of this was ancient history. The warehouse had been demolished in 1979.

Adam Weinberg: So it never would have occurred to us that when we were talking about Gordon Matta-Clark's piece being out there in the water that, within a short time, he would send this little sketch out of the blue to us without any note on it.

Carrie Mae Weems: A few days later, a sketch arrived in the mail from David . . .

Adam Weinberg: I had no idea what he was intending. I didn't think much about it. We put it aside because we were focused on getting the new building open. Then some weeks later, when I looked at the sketch again, I thought maybe this was a message in the bottle and that David was, in his own way, saying something to us, challenging us, enticing us, teasing us, making fun of us.

Carrie Mae Weems: Adam invited David back, and the sketch developed into an idea and, after five years, a work of public sculpture.

Adam Weinberg: He originally called it a monument to Gordon Matta-Clark because he wanted it to be identified so specifically with Gordon Matta-Clark. I asked him in a meeting years ago, "Is it a monument?" I said, "It's really sort of an anti-monument in a way." And then he said to me, "What did Gordon call the piece?" And I said, "Day's End." And he said, "A great tailor makes the fewest cuts. We will call it Day's End."

Carrie Mae Weems: Like the sketch, Day’s End is an outline of what was once. It’s like a spirit or a ghost, something that’s there or not there.

Guy Nordenson: In terms of the structure, it seemed pretty clear actually from David Hammons's sketch what it would be. There were details that evolved over time, but I was excited about the potential for it being quite thin, in the spirit of what the sketch showed, and what that would mean structurally, how that could be done.

Carrie Mae Weems: That’s Guy Nordenson. He’s a structural engineer who has helped artists and architects realize their visions.

Guy Nordenson: When you build a structure like a bridge or this sculpture, then you're out in the elements. Then of course, the corrosion is a big deal. You're out in the salt water. That took a while before we arrived at what we all wanted to use. We landed on a really advanced kind of stainless steel which has a great name, Super-Duplex, which is highly corrosion-resistant and also happens to be very strong and very ductile.

Catherine Seavitt: The thing should appear seamless, so it can be this ephemeral, ghost-like piece. I think that's really been the goal. And the challenge of the work in many ways is how to make it appear almost magical. That it just arrived there and it was effortless.

Carrie Mae Weems: Catherine Seavitt is an architect. She’s been working with Guy to overcome the challenges of building a permanent sculpture in the Hudson, a dynamic, ever-changing tidal river.

Catherine Seavitt: And I think that's kind of what's joyful about some things. They're mysterious. You don't understand how it could be made. But you know, anyone will know, like that must have been a lot of work. But there's a kind of moment when you dust yourself off and you're like, "Oh, it was nothing.”

Kellie Jones: If you're just having the kind of framework of a building that no longer exists, there's a way that it also engages our own imaginations to fill that space, to think about that space, and to really kind of meditate on what's there and what's not there. It's really about meditating on that absence, on that invisibility. Is it an invisibility of people, of housing? Of certainly thinking about Native American sovereignty in those spaces that may not be thought about. That kind of empty framework makes us think about what was there, not just last week, not just ten years ago, but generations ago, before New York.

Glenn Ligon: I think the relationship between David's project and Gordon Matta-Clark is because Gordon Matta-Clark was taking existing sites and transforming them, so that's very much David, too, taking some preexisting thing and working with it, transforming it. But in terms of his, David's project here, what I like about it is you're not exactly sure what he's transforming. Is it the Gordon Matta-Clark piece? Or is it the pier itself as a structure? Or is it both? In New York City, you have this notion of what the piers were, what the West Side Highway was, and the sort of life around the piers.

Adam Weinberg: We live in our memories as much as we live in our life. The way we are with other people is based on our memories of those people, whether the memories are accurate or not. So the memories are alive and objects out in the world, whether we can physically see them there now or not, are part of the subconscious of the culture. We act based on those memories out in the world and in the landscape. I think art functions that way, functions as a mnemonic device that is constantly a reminder.

Luc Sante: Well, an homage is an acknowledgement, an acknowledgement of the past, an acknowledgement of the fact that you were not sprung forth from the forehead of Zeus, an acknowledgement that you stand on ground that's been previously trodden. Any writer, any artist, and any painter, any sculptor, any photographer, at this point, has to acknowledge that their work is only made possible by the work of people who have gone by previously. So an homage is tipping your hat, tipping your hat and holding it over your heart. It's an acknowledgement. What can I say? It's a thank you note across time.

Carrie Mae Weems: Over the next four episodes, we’ll dive deeper into what Luc Sante so eloquently refers to as the ground that has been previously trodden. In our next episode, we will go back to the seventies, to the original Day’s End, and to a very different New York City.

Betsy Sussler: You would have walked into this dark, empty, musty, funky, smarmy place, site that had, you knew, all the potential in the world. I mean, here it was utterly abandoned on the shore of the Hudson in the West Village, which at the time was a huge gay scene. And gone, "Whoa." I mean, this is vast, and there's something very profound happening there because there's this darkness, but beams of light are coming through little crevices.

Thank you for joining us for the first episode of this five-part series of Artists Among Us, a podcast from the Whitney Museum of American Art.

To learn more about the voices you have heard here, please visit whitney.org/audio/podcasts. You’ll also find Artists Among Us wherever you get your podcasts. If you’ve enjoyed listening, please rate the show and share it with your friends.

The Whitney is located in Lenapehoking, the ancestral homeland of the Lenape. The Whitney acknowledges the displacement of this region's original inhabitants and the Lenape diaspora that exists today as an ongoing consequence of settler colonialism.

Special thanks to the artist, David Hammons, whose vision made this project possible.

Thank you to the City of New York, The Keith Haring Foundation, Laurie M. Tisch Illumination Fund and Robert W. Wilson Charitable Trust, and the many donors for their generous support to realize David Hammons, Day’s End, and a special thanks to the Joan Ganz Cooney and Holly Peterson Foundation and The Marlene Nathan Meyerson Family Foundation for their support towards the creation of this podcast, Artists Among Us.

Thank you to our host, Carrie Mae Weems.

Additional thanks to our many podcast contributors: Adam Weinberg, Glenn Ligon, Luc Sante, Bill T. Jones, Catherine Seavitt, Guy Nordenson, Tom Finkelpearl, and Kellie Jones. Special thanks to Kyle Croft, Alex Fiahlo, George Cominske, Jonathan Kuhn, Gina Morrow, Elle Necoechea, Sofia Ortega-Guerrero, Aliza Sena, Kathryn Potts, Stephen Vider, Sasha Wortzel, and Liza Zapol.

Original music for Artists Among Us and Day’s End was created by Daniel Carter and his collaborators.

This podcast was produced by SOUND MADE PUBLIC, with Tania Ketenjian, Katie McCutcheon, Jeremiah Moore, Mawuena Tendar, and Philip Wood. It was produced in collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art, by Anne Byrd, Jackie Foster, and Emma Quaytman.

Episode 1 - The Dawn of Day’s End

A Cathedral of Light on the Hudson River

Episode 2

“He went in with the chainsaws and his block and tackle and proceeded to cut it up. And what was most alarming to New York state authorities was that he’d actually cut the pier away from the mainland, so it was there, sort of floating, in the water.”

— Jane Crawford

How did the artist Gordon Matta-Clark transform a dilapidated shipping pier into a “cathedral of light”? In this episode, we trace the decline of Manhattan’s formerly flourishing meat markets and waterfront industries. Amid the decay, Matta-Clark spotted the potential for beauty.

Released May 21, 2021

In order of appearance: Betsy Sussler, Jonathan Weinberg, Jane Crawford, Andrew Berman, Tom Finkelpearl, Adam Weinberg, Laura Harris, Florent Morellet, Catherine Seavitt, Glenn Ligon, Jessamyn Fiore, John Jobaggy, Alan Michelson, George Stonefish, Curtis Zunigha, Eric Sanderson, Luc Sante

Around Day’s End: Downtown New York, 1970–1986. Exhibition website, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (Sept. 3–Nov. 1, 2020).

Taylor Dafoe. “What Is ‘Post-Stonewall Art’? Historian and Artist Jonathan Weinberg Breaks Down the Themes That Define the Era.” Artnet News, June 25, 2019.

Kyle Croft. “Cruising the Archive: Jonathan Weinberg on the History of the Piers.” Art in America, June 13, 2019.

Alan Michelson: Wolf Nation. Exhibition website, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (Oct. 25, 2019–Jan. 12, 2020).

Manna-hatta Fund in partnership with American Indian Community House. “History.” mannahattafund.org.

Jim Dwyer. “The Sounds of ‘Mannahatta’ in Your Ear.” New York Times, Apr. 25, 2017.

Elizabeth Kray. “Walking Tour: Herman Melville's Downtown New York City.” poets.org.

“Silky Love.” RadioLab. Podcast audio, Sept. 27, 2019.

“#296 Talking Trash: The NYC Department of Sanitation.” The Bowery Boys: New York City History. Podcast audio, Aug. 8, 2019.

“#180 The Chelsea Piers and the Age of the Ocean Liner.” The Bowery Boys: New York City History. Podcast audio, Apr. 16, 2015.

“Biographer Robert Caro.” Fresh Air. Podcast audio, Mar. 6, 2020.

0:00

Episode 2 - A Cathedral of Light on the Hudson River

0:00

Carrie Mae Weems: A public sculpture by the artist David Hammons, called Day’s End, has been permanently installed in the Hudson River. The construction was a collaboration with the Whitney Museum, and the work now belongs to the city of New York. But if you ask David, he’ll graciously tell you that, actually, the sculpture belongs to Gordon Matta-Clark.

Gordon Matta-Clark is the artist who built the original Day’s End on the same spot—Pier 52, on the edge of the Meatpacking District—nearly half a century earlier.

Betsy Sussler: You would have walked into this dark, empty, musty, funky, smarmy place, site that had, you knew, all the potential in the world.

Carrie Mae Weems: Bomb magazine editor Betsy Sussler was with Gordon as he scouted the pier before starting work on the original Day’s End.

Betsy Sussler: I mean, here it was utterly abandoned on the shore of the Hudson in the West Village, which at the time was a huge, gay scene. And gone, “Whoa.” I mean, this is vast, and there’s something very profound happening there because there’s this darkness, but beams of light are coming through little crevices. And Gordon, I think, was drawn to those beams of light.

Carrie Mae Weems: Gordon was an artist, like David Hammons, who used the city as source material. In his best-known work, he transformed buildings with a chainsaw that he used to cut into them. Once, he split an abandoned house in half, cracking open its domestic interior. For Gordon, cutting into the building wasn’t about destroying it but rather re-creating it and encouraging the public to experience them as sculpture. In the case of Day’s End, the work was on a grand scale.

Jonathan Weinberg: Kind of like a hangar space.

Carrie Mae Weems: Artist and art historian Jonathan Weinberg.

Jonathan Weinberg: Imagine a Costco that was emptied of all the stuff, or a gigantic Home Depot. That would be what it’s like.

Jane Crawford: The pier in those days was a meeting place for gay men. It was an enormous pier with a lot of broken glass on the ground and, outside, people were sunbathing. And Gordon went in to transform it, and he put up some signs saying “no trespassing” and “men at work.” And of course, it was just him and maybe one or two other people he convinced to help him.

Carrie Mae Weems: Jane Crawford, wife of the late Gordon Matta-Clark.

Jane Crawford: He went in with the chainsaws and his block and tackle and proceeded to cut it up. And what was most alarming to New York state authorities was that he’d actually cut the pier away from the mainland, so it was there, sort of floating, in the water.

Carrie Mae Weems: Welcome to Artists Among Us, a podcast from the Whitney Museum of American Art that reimagines American art and history. In this season, we take David Hammons’s sculpture, Day’s End, as a starting point. From there, we look into the many histories, mostly now invisible, that have shaped this site on the edge of lower Manhattan.

In episode one, we learned David Hammons used the city to create his work. In this second episode, we dive deeper into the original Day’s End.

Jane Crawford: Gordon liked to say that the layers of how we live in a room are like the layers of skin, and he considered himself a kind of urban archeologist, cutting through these layers to see how people had lived before.

Carrie Mae Weems: Today, we’re traveling backwards in time. We’ll start in 1970s New York City, and go back to when the Lenape were the primary inhabitants of the island, which was then called Mannahatta. Historian Andrew Berman.

Andrew Berman: To me, that’s still what I always think of when I think of the neighborhood, even as cleaned up and glamorized and different as it’s become today.

Carrie Mae Weems: This neighborhood is a stretch of land along the far west side of lower Manhattan, below 14th Street. Historically, it has always been a place of commerce. But when Gordon Matta-Clark created Day’s End, the neighborhood had been allowed to fall into a state of disrepair.

Carrie Mae Weems: Curator Tom Finkelpearl.

Tom Finkelpearl: And I hear people reminiscing about that, or especially young people, thinking about how great it must have been, and you have to remember that a lot of people are getting murdered. There were no jobs. But I think that these kinds of interventions, like what Matta-Clark did, was to see the beauty, or the potential beauty, in this wrecked urban space, and then intervene in a way that allowed you to see it.

Adam D. Weinberg: Matta-Clark wasn’t the only artist working on the piers.

Carrie Mae Weems: Here’s Adam Weinberg, Director of the Whitney Museum.

Adam D. Weinberg: There was actually an exhibition of art made on Pier 18.

Jonathan Weinberg: Pier 18 was really the idea of Willoughby Sharp, who invited twenty-seven male artists to create works of art on Pier 18, which is down by the World Trade Center in what we call Battery Park City now. Sharp’s idea was to ask these various artists to come up with different conceptual pieces.

Vito Acconci’s piece for Pier 18 is really amazing, in which he got his friend and artist Lee Jaffee to blindfold him and then while he’s wandering on the piers, it was Lee Jaffee’s job to make sure that Vito didn’t fall into the water. When this is photographed, it really looks like something from a film noir, as if Jaffee is not trying to keep Acconci from falling into the water, but is leading him to the water or going to kill him, because of the blindfold. Of course, one of the big associations of the waterfront is as a site of mafia corruption and teamster corruption.

Adam D. Weinberg: Artists just kept taking over the piers, long after Matta-Clark’s Day’s End was complete. Even in the early eighties a group of East Village artists transformed Pier 34 into a giant exhibition space.

Jonathan Weinberg: Pier 34 is at the end of Canal Street, and it was “discovered” by David Wojnarowicz, so it’s way down from the so-called sex piers. Basically, what happens is this group of artists squat in this space.

Adam D. Weinberg: Wojnarowicz, Peter Hujar, Mike Bidlo . . .

Jonathan Weinberg: They take it over and they start painting on the walls and creating all kinds of sculpture and installations in this amazing space. At a certain point, it was announced that there would be an opening and all these people are invited to come see the work. The police show up and shut it down.

It’s quite the same thing with Gordon Matta-Clark, I think you have to put your head into the mentality too that artists and young people had in the seventies, which was that the city and the government and the police were the sort of bad guys, and that doing this kind of thing, taking over these spaces was an act of freedom and liberation.

Carrie Mae Weems: Gordon saw an underlying beauty in these abandoned buildings that city planners and politicians simply ignored.

Laura Harris: He grew up in the era of urban renewal projects, large-scale urban renewal projects, in which parts of the city that were considered problems, or irrelevant and unimportant, were essentially razed to make way for fortress-like corporate spaces, and, quite commonly, freeways, bridges, tunnels, and other forms of passage to secure safe travel in and out of the city for suburban commuters.

Carrie Mae Weems: That’s NYU Professor of Media Studies, Laura Harris.

Laura Harris: That’s part of the backdrop for Matta-Clark’s practice, I think, is not wanting to participate in this kind of development, in this use of architecture, which depended in some ways on transforming the city through these brutal renewal projects.

Instead, he attempted to intervene in some ways by opening up what he considered abandoned structures to new possibilities.

Carrie Mae Weems: The Meatpacking District felt very different from the quainter New York neighborhood nearby, the West Village. And yet in many ways, it represents what New York is all about: a wide-ranging mix of people living and working side by side.

Andrew Berman: In addition to the meatpacking businesses, which were still very much there there was also this increasing concentration of these bars and clubs, both sex clubs and dance clubs.

Carrie Mae Weems: And it’s where Florent Morellet ran his in-crowd restaurant from 1985 to 2008. It was a favorite spot for artists, celebrities, and clientele of the neighborhood’s many gay bars.

Florent Morellet: I went to the Mine Shaft, the Anvil. And coming out at two, three, four o’clock in the morning was unlike any other club you came out [of] at that time, because you came out of the clubs, the city was dead. But you came out of those clubs in the meat market, and you had a neighborhood that was packed with traffic jam[s] and trucks, and people are going around yelling at each other like, “Move!” Taxis and meat-packers.

Catherine Seavitt: The meat market still persisted quite long, really until the last few decades, really.

Carrie Mae Weems: Architect Catherine Seavitt.

Catherine Seavitt: So, that brings you to the kind of stench of rotting meat or the smell of the carcasses or the blood from the animals, which are really being carved up inside of these buildings and then trucked around on . . . Not things unlike the garment racks that move around in the fashion district, but actually these would be carcasses rolling along wheeled carts with guys in white aprons wielding them.

Glenn Ligon: A visitor to New York is like, “Why was it called the Meatpacking District?”

Carrie Mae Weems: Artist Glenn Ligon.

Glenn Ligon: I was like, “Because there would be bloody carcasses hung on the street outside of the meatpacking shops that line the streets here.” And there would literally be blood running on the street.

Florent Morellet: In the early days, it stunk, yeah, especially in the warmer weather.

Andrew Berman: When I think of the Meatpacking District, I think of the smell, in terms of what it used to smell like, in part because of all of those meatpacking plants.

Florent Morellet: Rotten blood. But, you know, being close to the river, it’s an area where you have a little bit of breeze. But yeah . . . I mean, I remember whole sides of beef were on those rails.

Catherine Seavitt: There was still a kind of chaotic street life. Of course, the Belgian block that paved all of those streets in the Meatpacking District had a particular rattle for both cars and those carts of meat. So there was very much a kind of loud street life that persisted.

Carrie Mae Weems: When Gordon came to the Meatpacking District, meatpackers had already begun moving out, and the vibrant shipping industry of the early twentieth century was long gone.

Matta-Clark spent a total of three months cutting into the building’s floors and walls with chainsaws, transforming the space. But by doing this, he also temporarily displaced the people who used the piers for sunbathing, socializing, and sex. We’ll spend more time with them in our next episode. And while he was trespassing on their space, he was also legally trespassing. After he finished the work, a warrant went out for his arrest.

Jonathan Weinberg: One of the things that made it so dangerous is that he actually made cuts in the floor to reveal the water, and he made a little bridge. So you would see these big cuts, both on the floor . . . as if the light coming through this huge, arc-like shape had sort of cut holes into the floor—like beams of light had cut holes into the floor.

Laura Harris: The play of light and wind and rain and all the elements he’s allowing in on the structure. The way that it penetrates one hole and exits another hole. The way that the light and shadows and the whole atmosphere of the space changes over the course of the day, from beginning to day’s end is what he’s interested in at that moment.

Jonathan Weinberg: If you stayed there long enough, you’d watch the sun setting, which, to him, was the ultimate narrative of the piece. That’s why it’s called Day’s End because you’re watching the movement of the light through it.

Carrie Mae Weems: Jessamyn Fiore is the . . .

Jessamyn Fiore: . . . curator as well as the co-director of the Gordon Matta-Clark Estate. He really talked and spoke and wrote about Day’s End as a kind of public park, that he wanted it to be experienced through all four seasons. He wanted to see how the light changed in the space for all four seasons. He wanted people to enter the space that was once dark and dangerous and foreboding, and now had been opened up and was a celebration of light and water and just being in this place that is the island of Manhattan. And for people to be able to access that and have that experience, and look at their environment in a new way.

Jane Crawford: Gordon had more energy than all of us here in this room.

Carrie Mae Weems: Jane Crawford was married to Gordon Matta-Clark until his death in 1978 at the age of thirty-five from pancreatic cancer.

Jane Crawford: He was very magnetic, a personality. He was always laughing and joking and very engaging with other people. I used to say he’d go out in the morning to buy the newspaper on the corner and came back with two or three people he’d just picked up on the street. And, you know, they could be anywhere from homeless to students to a nuclear physicist he came home with once.

The pier was lovely inside because you could hear not only the lapping of the water and the boats, the tugboats honking their horns and the little boats honking their horns, but there’s also just this lovely murmur of the city at a distance, which I always found somehow very romantic. You’d hear sirens and cars honking, but always from a distance, so that was like the subliminal soundtrack of the pier, if you will.

Betsy Sussler: The interior, of course, is what Gordon was drawn to. And he wanted to bring light into it. And he never told me until the eleventh hour what environment he had picked to go film, or to go do a piece, or an intervention, or an architectural intervention in. So this really was, one morning, we woke up and he said, “Grab your Super 8, we’re going to go, and I’ve got this whole thing planned.”

Carrie Mae Weems: Betsy Sussler filmed the making of Day’s End.

Betsy Sussler: And there he was with the pulleys and the saws, and I just filmed. I really just caught the action wherever I could, the light coming in.

Jessamyn Fiore: I think when looking at what Gordon was doing with making these cuts in buildings, it’s important to remember that it wasn’t about destruction. He wanted to transform the spaces.

Laura Harris: There’s a level at which he’s interested in imagining what else might a building look like if you let light in this way? What might it feel like if you let sound or wind in in this way? But also what other interactions might emerge if you reshaped buildings or opened them up in this way?

Jessamyn Fiore: And he talked about how he felt, that people, everyday people, were too timid in their own spaces. That in fact, we have the ability to change our spaces, even if that change is by cutting holes in them.

Jonathan Weinberg: He’s one of those artists that he just touches something, and he decides, I’m going to cut this out and then it’s going to be a work of art. I’m very drawn to, I guess, the sort of notion of the artist as an alchemist, which I think is a theme that recurs in his work. To me, that’s what artists do. They’re transformative, they transform things, and they create something that is magical that truly opens up the world . . . creates a kind of moment of freedom.

Carrie Mae Weems: The artist as alchemist is a useful way of thinking about both Matta-Clark and David Hammons. But their artistic parallels don’t simply stop there.

Laura Harris: One might imagine Hammons’s piece as a picking up of where Matta-Clark left off. What he did was highlight and bring to our attention a kind of practice that he is also inviting us all to take up in our own ways. A creative inhabitation of space, a creative rearrangement of space, for example, a creative reworking of the city to open up the possibilities for how we might perceive and how we might live.

Jessamyn Fiore: I think that the spirit of both Gordon’s work and the David Hammons sculpture is for people to relook at their own urban space, urban existence, to connect with the history of generations that have come before in this place and its architecture. And just the spirit of creativity and art and possibility that is, to my mind, ingrained in this city, in its soil even.

Carrie Mae Weems: The ground beneath Day’s End and the Whitney Museum has a rich and storied history.

Adam D. Weinberg: The Museum is on Gansevoort Street. And Day’s End is just at the end of Gansevoort Street, on the peninsula. In fact, the name goes back to the early nineteenth century. It comes from Fort Gansevoort, which during the War of 1812 to defend against the British—in fact, it was never actually used. And the fort itself was named for a Revolutionary War hero, Peter Gansevoort.

Andrew Berman: Many of the streets in Greenwich Village are named, in fact, for Revolutionary War heroes. All of those named streets that still survive south of Washington Square Park, like Sullivan, Thompson, and MacDougal. Those were Revolutionary War heroes. Colonel Gansevoort was a slaveholder, as were many New Yorkers at the time. New York, interestingly, while it was a center of abolitionist activity, it was also a center of a lot of slave-owning and slave trading.

Adam D. Weinberg: Some of the abolitionist activity in fact took place relatively close to the Museum. There was the African Free School in Greenwich Village, and teachers worked really closely with Black children there to try to get them to think positively about the notion of emancipation, and to prepare themselves for it. And there was also a community around Zion Methodist Episcopal Church, which was in the West Village, which included Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman. And I think the church was also a stop on the Underground Railroad.

Peter Gansevoort was also Herman Melville’s grandfather. After the Civil War, Melville worked on Gansevoort Street as a customs inspector. He became a customs inspector because Moby-Dick was an incredible financial failure, which most people don’t realize. He was pretty much unemployed, working for four dollars a day, and even adjusted that wasn’t so great. I remember reading that he hated his job, and he said it was “worse than driving geese”—which I find particularly amusing, because the name Gansevoort in Dutch means “the lead goose,” the goose that leads the V that cuts across the sky. And his office was on West Street, right where Gansevoort Street hit the river.

Andrew Berman: As the nineteenth century went on, you had bigger and bigger piers on the west side. The industrial revolution also led to a landfill. So, you had the land being added to and built out, with everything from sort of waste and garbage to dirt and soil. And you certainly saw factories starting to crop up, especially along the waterfront, including in Greenwich Village.

And along the waterfront, in addition to all of these very, very busy piers and the factories, you also had a lot of sailors’ hotels, because you had a lot of folks who worked along the waterfront.

Some of them were quite notorious, had a sort of Barbary Coast kind of flavor to them.

And then interestingly, there were some that were set up by these sort of missionary charitable organizations to give sailors a wholesome, healthy place for them to stay during their time in port.

Catherine Seavitt: The site on which the Whitney now sits used to be Gansevoort Market. It was an open-air market, where commerce, where there was mostly vegetable produce, was brought by horse and cart. And it was an outdoor fruit market, essentially, fruit and vegetable market. And that’s really like the end of the nineteenth century.

Andrew Berman: One of the reasons why it did develop as a market neighborhood was in part because of its proximity to the river, and there used to be these great big piers that were located there. Pier 54, actually, which no longer exists was the pier where the survivors of the Titanic were brought when they were rescued. It’s also where the Lusitania left, where it shipped out of New York on its fateful journey.

Catherine Seavitt: Later, there’s actually a new, enclosed, structured market called the West Washington Market, which goes up just across the street on the Gansevoort Pier, exactly where Pier 52 was located and is now the site of Hammons’s sculpture.

Andrew Berman: These were large, large piers that accommodated the biggest ships of their day.

Catherine Seavitt: That enclosed market was quite novel in many ways, because they could actually start to sell produce that was meat-based or animal-based. So both dairy products as well as meat products could be sold there because of this advent of refrigeration. And it was because of this refrigeration that meat could be safely packaged for the market in these buildings.

Andrew Berman: The High Line was sort of this strange intervention in the kind of dying days of commerce and industry, or at least of that traditional kind of commerce and industry along the West Side.

Catherine Seavitt: Essentially the rail, the trains were running on grade, initially, so at the street level. And there were even, I think it was called the “avenue of death.” It was pretty dangerous for pedestrians who were walking around in the neighborhood because they were basically at risk of being run down by trains. There were even these guys, cowboys on horses, who would try to control pedestrian and horse and wagon traffic from collisions with the train. So they would basically police people and keep them out of the way of the trains when they were oncoming.

Andrew Berman: The funny thing was that they did it, I guess they couldn’t quite see it coming, but certainly at this time period, we were really beginning a pretty dramatic shift away from this method of transporting goods. So, the High Line was built in the thirties. The Second World War happened, and after the Second World War, there was a huge shift away from that kind of transportation.

Then when trucking became the more predominant way of goods like the meats were moved in and out, its proximity to the West Side Highway also was an important part of how and why the Meatpacking District functioned there.

Carrie Mae Weems: John Jobaggy is a third-generation meatpacker and grew up in the neighborhood, watching his father and grandfather do business.

John Jobaggy: When I first came down here, you had a lot of Western European immigrants. And they were primarily guys from farms; they weren’t kids from cities. These were farm kids who came to America—poor kids, like my grandfather—to make a better living for themselves. They weren’t growing up in mansions, coming to New York to be meatpackers, to be butchers.

You got to remember, it went from 15th Street and 9th Avenue over to 10th Avenue, and it went from 15th. Fourteenth Street was the main street. And then you had a few meat companies past Gansevoort Street, from 9th to 13th. So you had them four blocks north, south, and two blocks east, west. And all the buildings, nothing was empty.

Andrew Berman: One of the things that’s so interesting about the neighborhood’s history is how many of the really famous bohemian haunts of the twentieth century were places that were run by Italian immigrants, Irish immigrants. And it was in fact that sort of sense of this close knit, intimate community that existed outside of the contemporary mainstream of American culture and society that really drew a lot of these artists and writers and painters to these places, both the neighborhoods and specifically these bars, coffee houses, cafes.

John Jobaggy: Every store front, big and small, was full. And it was a community, and people loved it, and everybody knew each other, and all the bosses, it was almost like a club. And the bosses would get together. There was a restaurant called Frank’s Restaurant on Washington Street and 14th Street, and the bosses would get together; a lot of them would like to have their little cliques. They would meet every day for breakfast together. And they loved to talk about, “Where’s the pork market? Where’s this market? Where’s the beef, where’s prices going?” And just, socially and business-wise, chat. And they loved it. Loved it.

Andrew Berman: Certainly, I would not say that the neighborhood was without conflicts or tensions. There’s also just a wonderful history of kind of mixing and interaction that really shaped the character of the neighborhood tremendously.

Carrie Mae Weems: This vibrancy in people, sound, in exchange of some kind, has always been part of the neighborhood.

Catherine Seavitt: I think the fascinating aspect of that site in which the Whitney is now planted—the downtown Whitney—is that it’s always been historically a place for trading, a trading place. A place of exchange, a trading post. In fact, it goes all the way back to the Lenape peoples. Sapokanikan is the name of the trading post, which was actually at that very point on the Hudson River shoreline on Manhattan Island.

Alan Michelson: It was called Sapokanikan, which, in the Lenape language, is thought to mean tobacco field or place where tobacco grows.

Carrie Mae Weems: That’s Alan Michelson, a New York City-based artist, and a Turtle Clan Mohawk member of Six Nations of the Grand River.

Alan Michelson: I was fascinated by the fact that the name of that Lenape settlement had survived, and that the Whitney landed on that site four hundred years later. So four hundred years ago, in the early days of the New Amsterdam colony, that area was a beach and a small settlement. There was probably fishing and planting, maybe more than tobacco, and a place of trade. And that was trade that probably included trade not just among the immediate groups of Lenape and the sub nations, but groups like the Haudenosaunee, my ancestors, who were upriver.

Carrie Mae Weems: In the fall of 2019, Michelson had a solo exhibition at the Whitney called Wolf Nation. His idea was to investigate the layered histories of the place and to reveal its Indigenous history. His work reminds us that we stand on land that has a long and complicated history—one that challenges us, one that was not taught to us in school.

Alan Michelson: It’s a significant site, a significant Native site, one of many that basically are covered with concrete and buildings, not just in Manhattan, but across the country. And I just wanted to use that opportunity of showing at the Whitney to bring that history to light.

Carrie Mae Weems: George Stonefish is an elder of the Lenape Nation, and a longtime New Yorker.

George Stonefish: Most New Yorkers, if you ask them what natives met the Dutch, they don’t know. They don’t know it was the Lenape. All they’ll tell you about, we know they sold the island of Manhattan for twenty-four dollars, and that’s the limit of their education. We came from this area, and we were chased ultimately, and settled here, and were chased again. And we were massacred at that one spot where we are presently at right now. And that whole history of going down and so forth, people should know of.

Carrie Mae Weems: Curtis Zunigha is a Lenape Indian.

Curtis Zunigha: Well, that’s kind of the way Lenapehoking was. It wasn’t just one homogenous people. There were common language, and lifeways, and religious ways, but they were still more of a collective than one homogenous group.

Carrie Mae Weems: Eric Sanderson.

Eric Sanderson: If we were here in the early seventeenth century, coming into New York Harbor, we would have seen a long, thin, wooded island, which is, the local people called Mannahatta. Maybe you would have seen Lenape canoes. They would make them out of these tulip trees, these very tall, very straight tulip trees. We think Sapokanikan, near where the Whitney is, is a place where they would cross the river to trade with the people over in Hoboken, and back and forth. You might even have caught a glimpse of a trail that would have gone back into the forest, and then down through Greenwich Village, and then on to the main north, south trail that was on the east side of Manhattan, somewhere around Murray Hill, and so forth. Would have been really extraordinary.

Catherine Seavitt: So it goes from being this site of Lenape exchange, connecting to waterfront and terrestrial voyaging paths, let’s say, or pathways, to this more commercialized produce market and then a meat market, but always about this place of exchange that's tied to both the river, to other transportation systems such as rail and road or trail, all within this little nexus. So it’s a fascinating site.

Carrie Mae Weems: I’m pretty sure that neither Matta-Clark nor Hammons had these histories at the top of their minds when they conceived their versions of Day’s End. But each work, in its own way, opens up a hole or an absence into the day-to-day, inviting reflection on what stories or what histories have passed from view, [been] ignored, or been denied.

Carrie Mae Weems: Artist Glenn Ligon.

Glenn Ligon: I think that sort of idea of the past being present is always in David’s work, partially because the materials he often uses have another life. And so he’s literally taking something that someone else has used, or someone else has discarded, and sort of thinking, making new objects with it.

Carrie Mae Weems: Writer, critic, and artist Luc Sante.

Luc Sante: And I believe that you can’t really live in the present, unless you have the past to look back upon. It would be like deciding that you’re a writer or a student of literature but are unwilling to acknowledge the literature of the past. Obviously, you can’t do that. You’re standing on other shoulders.

Betsy Sussler: It’s that old Faulkner adage, “The past isn’t dead. It’s not even past yet.”

Luc Sante: And it’s the same for things that are less specific, things that are more subjective about the past and about the way it affects you and the things that you see on the street, the stories that are handed down. We don’t just exist in this one present moment. We’re also existing in a spectrum of time.

Narrator: You have been listening to Artists Among Us, a podcast from the Whitney Museum of American Art. Over the next three episodes, our exploration continues: looking more closely at the queer community that frequented the Meatpacking District in the seventies.

Efrain Gonzalez: On the weekends it was full of men. You’d have guys just sitting there, cruising. You would have people bring some Chinese food and you would eat, or drink a beer, smoke a little something, watch the sunset. It was a great place just to sit and watch the sunset. And people would come in with little towels and they would lay the towels down and they would sunbathe on these rotting wooden piers. At night people would just sit there and look at the stars, or cruise one another. You could sit on the pier all the way at the end, be all alone and look back and you could see the city all lit up at night. That was really nice.

Narrator: To learn more about the stories you heard here, visit whitney.org/audio/podcasts. You’ll also find Artists Among Us wherever you get your podcasts. Rate, share, tweet, and, if you’re in New York City, across the street from the Whitney, listen and do some time traveling.

The Whitney is located in Lenapehoking, the ancestral homeland of the Lenape. The Whitney acknowledges the displacement of this region’s original inhabitants and the Lenape diaspora that exists today as an ongoing consequence of settler colonialism.

Thank you to everyone who contributed to this podcast: Luc Sante, Catherine Seavitt, Betsy Sussler, Laura Harris, Jane Crawford, Jessamyn Fiore, Eric Sanderson, Jonathan Weinberg, Glenn Ligon, Alan Michelson, Andrew Berman, Tom Finkelpearl, Florent Morellet, Adam Weinberg, Curtis Zunigha, and George Stonefish. Thanks also to oral historians Liza Zapol who interviewed John Jobaggy, and Sara Sinclair who interviewed Curtis and George. Special thanks to Elle Necoechea, Sofia Ortega-Guerrero, Aliza Sena, Jackie Foster, and Helena Guzik.

Original music for Artists Among Us and Day’s End was created by Daniel Carter and his collaborators.

This podcast was produced by SOUND MADE PUBLIC, with Tania Ketenjian, Katie McCutcheon, Jeremiah Moore, Mawuena Tendar, and Philip Wood. It was produced in collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art, including Anne Byrd and Emma Quaytman.

Episode 2 - A Cathedral of Light on the Hudson River

Latex and Lard in the Meatpacking District

Episode 3

“The mid-seventies was, depending on your perspective, either the greatest or the worst time in New York’s history. I think arguably, it was a little of each.”

— Andrew Berman

A vibrant Queer community inhabited Manhattan’s Meatpacking District when Gordon Matta-Clark created a sculpture by carving into Pier 52 on the Hudson River. This episode recalls a golden age when sex, art, and creativity converged on the waterfront in the years prior to the AIDS crisis in New York City.

Released May 28, 2021

In order of appearance: Andrew Berman, Betsy Sussler, Efrain Gonzalez, Paul Gallay, Jonathan Weinberg, Laura Harris, Egyptt LaBeija, Tom Finklepearl, Glenn Ligon, Randal Wilcox, archival recording of Alvin Baltrop, Luc Sante, Elegance Bratton, Stefanie Rivera, Catherine Seavitt

“The Clit Club Crew on the Clit Club for the 6th Annual Last Address Tribute Walk.” The Visual AIDS Blog, July 3, 2018.

Visual AIDS. “Past Event - Last Address Tribute Walk: Meatpacking District - Whitney Museum Screening & Meatpacking District Doorstep Readings.” visualaids.org. May 12, 2018.

Victor Ultra Omni. “Interview with Icon Egyptt Labeija.” The Center For Black Trans Thought (blog), Nov. 1, 2018.

Pier Kids: The Life. “Pier Kids TRAILER.” YouTube video, 01:00. Sept. 30, 2019.

Ben Miller. “Photos: Efrain Gonzalez Chronicled NYC’s Seedy, Glorious West Side Nightlife.” Gothamist, Mar. 24, 2014.

The Life and Times of Alvin Baltrop. Exhibition website, The Bronx Museum of the Arts, New York (Aug. 7, 2019–Feb. 9, 2020).

“Live from Stonewall.” Making Gay History | LGBTQ Oral Histories from the Archive. Podcast audio, May 23, 2019.

“Remembering Stonewall: 50 Years Later.” StoryCorps. Podcast audio, June 25, 2019.

0:00

Episode 3 - Latex and Lard in the Meatpacking District

0:00

Andrew Berman: The mid-seventies was, depending on your perspective, either the greatest or the worst time in New York’s history. I think arguably, it was a little of each.

Betsy Sussler: It was a very vibrant time. It was also a very dangerous New York. But it was not yet a New York that was real estate driven, because prices were low. So we could live cheaply. We could produce and have part time jobs. And do two jobs at once, the art job and the make a living job. And it was smaller, so that when you went out, you ran into almost everyone you knew and the conversations were constant.

Carrie Mae Weems: I’m Carrie Mae Weems, welcome to Artists Among Us, a podcast from the Whitney Museum of American Art that reimagines American art and history. In this five-part season, we’re looking at the changing landscape of the Meatpacking District of New York through the lens of the artist David Hammons’s sculpture, Day’s End. In this episode, we look at the Meatpacking District through the eyes of the LGBTQ community.

Nineteen-seventies New York is famous for its mix of creativity, social action, upheaval, unrest, and change. Artists who filled the city were making work and constantly collaborating. Industries that had long been based in the city were slowly moving away. And this left behind enormous loft spaces that would become the homes and studios for artists.

It was in this climate that artist Gordon Matta-Clark chainsawed openings into the floor of an enormous warehouse on Pier 52 in the Hudson River, creating a work of art that he called Day’s End. The work was on the edge of the Meatpacking District—but at the time, there were fewer and fewer meat-packers who actually lived and worked in the area.

Another set of changes impacted the neighborhood as well. These had their roots in the nearby West Village, towards the end of the 1960s. That neighborhood had long been a place where members of the queer community socialized. But it wasn’t really a free or open environment.

[archival audio]

Police routinely arrested and fined queer people, leaving marks on their permanent records and often outing them to their families and their workplaces. In June of 1969, the police raided the Stonewall Inn, arresting thirteen of the patrons. Over the next six days, lesbian, gay, and transgender protesters came together in resistance.

[archival audio]

In the wake of the Stonewall uprising, the fight for LBGTQ rights intensified, and there was a new sense of sexual freedom. By the time Matta-Clark started work on Day’s End, that freedom was finding expression in the Meatpacking District. Historian Andrew Berman.

Andrew Berman: There was this sudden, profound freedom that gay men had that they'd never had before, so there was definitely an explosion of sex in the neighborhood and the Meatpacking District was really an epicenter for that in a lot of ways.

Carrie Mae Weems: Photographer Efrain Gonzalez has been photographing queer culture in New York for decades.

Efrain Gonzalez: This was at a time where you could go in and discover your sexuality. That’s what I was doing in the Meatpacking. I was discovering my sexuality. When you live on Long Island and go to Catholic school, your sexuality is whatever they tell you it is. Then you come here, and you find men going into a hole in the wall, what’s in the hole in the wall, men having sex. And you begin to realize: I want to go into the hole in the wall; I want to go into the bar. You may be scared because you have no idea what’s going on. But you still have that desire, you still have that thing inside you that says, I want to go in that hole in the wall.

Carrie Mae Weems: Imagine for a moment: 1970s New York, particularly the West Side, where the city meets the Hudson River. Educator and Riverkeeper president, Paul Gallay.

Paul Gallay: The Greenwich Village waterfront was forsaken. It was littered with abandoned cars, the pier heads and the sheds were rotting and beginning to collapse into the Hudson.

Carrie Mae Weems: Critic Jonathan Weinberg.

Jonathan Weinberg: One of the things that happens at this point is that the West Side Highway, there’s this truck that shouldn’t have even been on the West Side Highway, and it creates this big hole.

Carrie Mae Weems: The former highway became a kind of wall between the piers and the city, so that you had to work hard to get to the water’s edge.

Jonathan Weinberg: A lot of times, ruins, dilapidated places exist on the edges of the city, you have to go out to them. What was extraordinary about this is that it was right in the center, right next to some of the richest real estate in the country.

Carrie Mae Weems: Historian Andrew Berman.

Andrew Berman: We have these incredible pictures of these pier structures that are sort of collapsing onto themselves, that are kind of empty. People are using them and they're sunbathing on them.

Jonathan Weinberg: There’s this sense that this is a place where the basic rules don’t apply, in which you can kind of escape from those rules—whether it means you can have a certain kind of sex, or you can be naked.

Carrie Mae Weems: NYU professor of media studies, Laura Harris.

Laura Harris: Where certain forms of sociality, certain forms of social and sexual encounter that were not otherwise accommodated by the city found a place, and found opportunity for expression.

Jonathan Weinberg: People talk about the piers as being abandoned: that’s the description, the “abandoned piers.” In many ways, they weren’t abandoned, they were being repurposed by artists. There was also homeless people lived there, there were sex workers, there were all kinds of activities that were going on in those places.

Laura Harris: That’s part of the backdrop for Matta-Clark’s practice, he attempted to intervene in some ways by opening up what he considered abandoned structures to new possibilities. Often they weren’t fully abandoned, as in the case of Day’s End where people were actively using that space. They were not considered legitimate users. Their uses were criminalized, but they were still actively using the space.

Carrie Mae Weems: BOMB magazine editor Betsy Sussler:

Betsy Sussler: I would go on exploratory walks through New York with Gordon Matta-Clark, because he would be deciding what he was going to film or if he was going to do a piece in that particular instance. And we were walking on the High Line and it, at the time, was a shanty town. It was a home for, mostly, homeless men. And I went, “Gosh, Gordon, should we be here?” And he said, “Just remember, they are more at risk than you are.”

Laura Harris: There is a danger that Matta-Clark mentions and others mentioned that there are muggers who take advantage of people who are not otherwise always in a position to immediately protect themselves. There is a lot of signage up, warning other people about muggers, taking care of one another, watching out for one another in the space.

Jonathan Weinberg: There was a gay guy who published a newsletter and also spray painted warnings on the walls of the buildings warning gay men not to go into them and that they would be mugged. I loved that sort of idea because he knew that the police, at that point, were not arresting gay men for trespassing, like they would have, but they didn't seem to care if they got killed, or something bad happened to them, or they were mugged.

Carrie Mae Weems: Activist Egyptt LaBeija was a star of the ballroom scenes on the piers.

Egyptt LaBeija: People that would come down here were targeted at times because of who they were. That’s why we never stayed alone, you always walked with someone. You kept in contact. If you’re going somewhere, you let someone know, this is where I’m going, especially at night time.

Andrew Berman: You sort of developed this kind of interesting parallel worlds there, which was the meat-packers who typically arrived at four o’clock in the morning and worked until about noon. The clubgoers and the bars that open in the late evening hours and often operated until the wee hours of the wee hours of the morning. And typically in the afternoon into the early evening, the streets of the neighborhood were pretty empty and deserted.

Efrain Gonzalez: The most dangerous thing were the dumpsters that were full of lard, rendered fat, that were leaking. And there’d be like a layer of lard on the sidewalk, dripping into the gutter. And imagine you’re wearing, like, your best leather, your finest domination gear, and you have to tippy-toe through this layer of slick lard, hoping and praying you don’t slip and fall down.

Carrie Mae Weems: The pier was a hangout spot both night and day: a place for cruising, reading, just spending time relaxing. By the early 1980s, artists like Peter Hujar, David Wojnarowicz, and Tava would become known for mixing sex and artmaking on the piers. But when Matta-Clark made Day’s End, Pier 52 wasn’t a place people would go looking for avant-garde sculpture.

Jonathan Weinberg: I had no idea that Matta-Clark actually had made this, now famous, site-specific work of art in the same place where so many gay men would go for anonymous sex or to sunbathe. The other thing about the work, which I think is so interesting, is how the work disappeared in an interesting way into the landscape that so many of the people who photographed it told me that they didn’t know that it was a work of art. They just thought it was part of the structure of the building. The Triumphal Arch that nobody knew was a Triumphal Arch. The photographer taking the picture without knowing what it is.

Carrie Mae Weems: Curator Tom Finkelpearl.

Tom Finkelpearl: I mean, I feel like works like Day’s End were not seen by many people. I’ve never met anybody who’s seen it. That’s not true. I met one person. But it was a gesture, and then sort of the friends got to know that it was happening. But it became legendary, it was a very photogenic work, because it was this intervention in this space.

Jonathan Weinberg: Matta-Clark talks about that in an interview, how he anticipates in any particular work that he does that it is going to change and disappear in some ways. Even as, usually, it’s a ruin that allows him to do the kind of cutting he’s going to do because, in a beautiful new house, they’re not going to allow Matta-Clark to come and split a beautiful new house. He had to find buildings that nobody wanted, or he thought nobody wanted, that he could do his thing to.

Carrie Mae Weems: Most people have only seen the work through photographs or films, including some beautiful, haunting ones taken by an artist named Alvin Baltrop. Here’s artist Glenn Ligon:

Glenn Ligon: I never saw Matta-Clark’s Day’s End, the pier piece. Never saw it in person. My understanding of it mostly is through Alvin Baltrop photographs, him taking photographs on that pier because that pier was a cruising site. And so I sort of learned about Matta-Clark through Baltrop, but also learned about what the West Side piers were through Baltrop. So those two things are kind of fused in my head.

Carrie Mae Weems: Alvin was a Navy veteran taking photographs in New York City, especially around the piers. One day, he was introduced to Randal Wilcox, who eventually became the trustee of the Alvin Baltrop Trust and knows work probably better than anyone else.

Randal Wilcox: After about ten minutes of looking through his work, I was just immediately stunned by it and by all the stories that he was telling me. And I said to myself, “Wait, this man is a genius. This stuff needs to be in a museum.” In a nutshell, I would say that he’s one of the most underrated photographers and visual artists of the last part of the twentieth century.

Carrie Mae Weems: Not everyone felt that way about Alvin’s work. These days, his work is revered. It’s shown in exhibition galleries around the world. But in the seventies, and for most of his lifetime Alvin was treated as an outsider—or worse. Here he is, speaking to Randal Wilcox, in a recording from 2000.

Alvin Baltrop: One woman said, “As I turn the pages of your portfolio, I can honestly say I’m afraid of your portfolio.” And I said, “why?” And she said, “Because I am afraid to see my husband or my son pop up in one of your photographs.” She said, “You must be a real sewer rat that you crawl around at night and photograph things like this. So I have to consider you a real sewer rat type of person and I don’t know if I like you.” I closed my book and walked out.