Stuart Davis

1892–1964

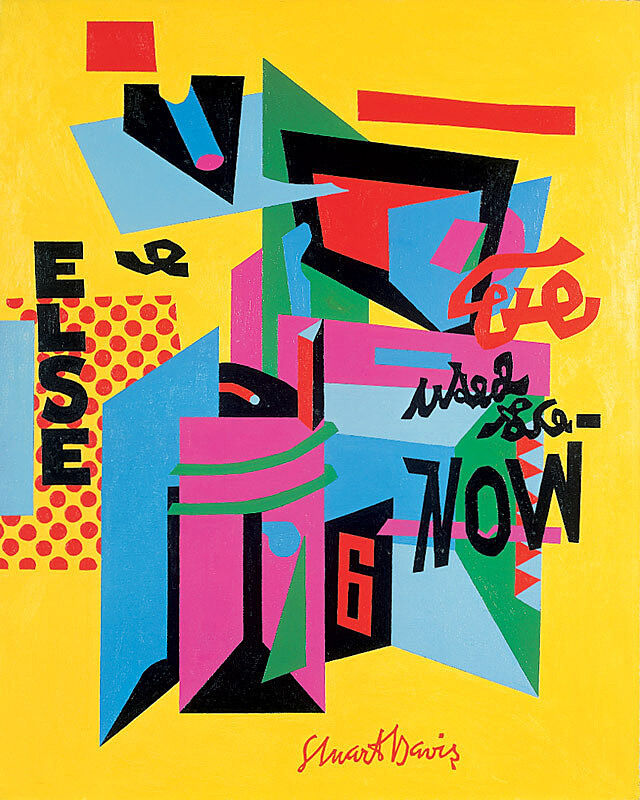

During the 1920s Stuart Davis developed an innovative style that fused the abstracted geometries of European Cubism with subject matter derived from American popular culture, especially advertising, newspapers, and everyday consumer objects. In late 1927 he began a series of four still-life paintings based on a grouping of unlikely items: an eggbeater, an electric fan, and a rubber glove that he had nailed to a table in his studio. During the year he spent working exclusively on the series, Davis homed in on the most essential formal properties of the objects. “Gradually through this concentration,” he remarked, “I focused on the logical elements. . . . The immediate and accidental aspects of the still life took second place.” In Egg Beater No. 1, the most flat and austere work of the series, Davis transformed his subject into a rhythmic arrangement of geometric forms, reaching a level of abstraction that was unprecedented in his work.

More often during the 1920s and 1930s, Davis’s real-world sources were abstracted but still recognizable, as in House and Street, which depicts the intersection of Front Street and Coenties Slip in lower Manhattan. The painting’s split image suggests the Cubist ambition to portray multiple viewpoints simultaneously, but its distinctively New York subject matter, including the Third Avenue elevated train, sets it apart from European precedents. Davis used the urban landscape to explore his fascination with the graphic language of signs and advertisements: the painting includes the word Front, for Front Street, the bell icon of the city’s telephone company, and the name Smith, which likely refers to Alfred E. Smith, the popular governor of New York State who was running for reelection in 1926, the year Davis made the drawing on which this painting was based.

In the final years of his career, Davis frequently used earlier compositions as springboards for new paintings marked by a complex language of unmodulated planar forms and densely woven lines. The Paris Bit is based on the canvas Rue Lipp, a cafe scene he produced during his Paris sojourn in 1928. With its inclusion of the number twenty-eight and the words eau, Belle France, and tabac, Davis pays homage in The Paris Bit to his earlier composition and his seminal experiences in Paris, where he was able to study Cubism firsthand. At the same time, the painting’s enlarged 110 Willem de Kooning b. 1904; Rotterdam, Netherlands d. 1997; East Hampton, NY 111 scale and network of calligraphic forms reflect the influence of vanguard American painting in the 1950s, especially Abstract Expressionism. The words “lines thicken,” added to the painting’s outer border, seem to acknowledge the painting’s more solid rendering in comparison with its earlier counterpart.

Introduction

Edward Stuart Davis (December 7, 1892 – June 24, 1964) was an early American modernist painter. He was well known for his jazz-influenced, proto-pop art paintings of the 1940s and 1950s, bold, brash, and colorful, as well as his Ashcan School pictures in the early years of the 20th century. With the belief that his work could influence the sociopolitical environment of America, Davis' political message was apparent in all of his pieces from the most abstract to the clearest. Contrary to most modernist artists, Davis was aware of his political objectives and allegiances and did not waver in loyalty via artwork during the course of his career. By the 1930s, Davis was already a famous American painter, but that did not save him from feeling the negative effects of the Great Depression, which led to his being one of the first artists to apply for the Federal Art Project. Under the project, Davis created some seemingly Marxist works; however, he was too independent to fully support Marxist ideals and philosophies.

Wikidata identifier

Q704588

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed February 16, 2026.

Introduction

Originally a magazine illustrator, Davis seriously turned to painting after viewing the Armory Show of 1913. His works featured banal images (a cigarette packet, signs, notices), altered with strong colors and words in script, suggesting the rhythm of an urban environment suffused with jazz. Comment on works: abstract

Country of birth

United States

Roles

Artist, painter

ULAN identifier

500115507

Names

Stuart Davis, Davis

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License. Accessed February 16, 2026.