Georgia O'Keeffe

1887–1986

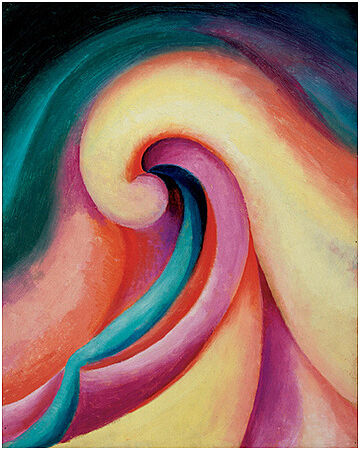

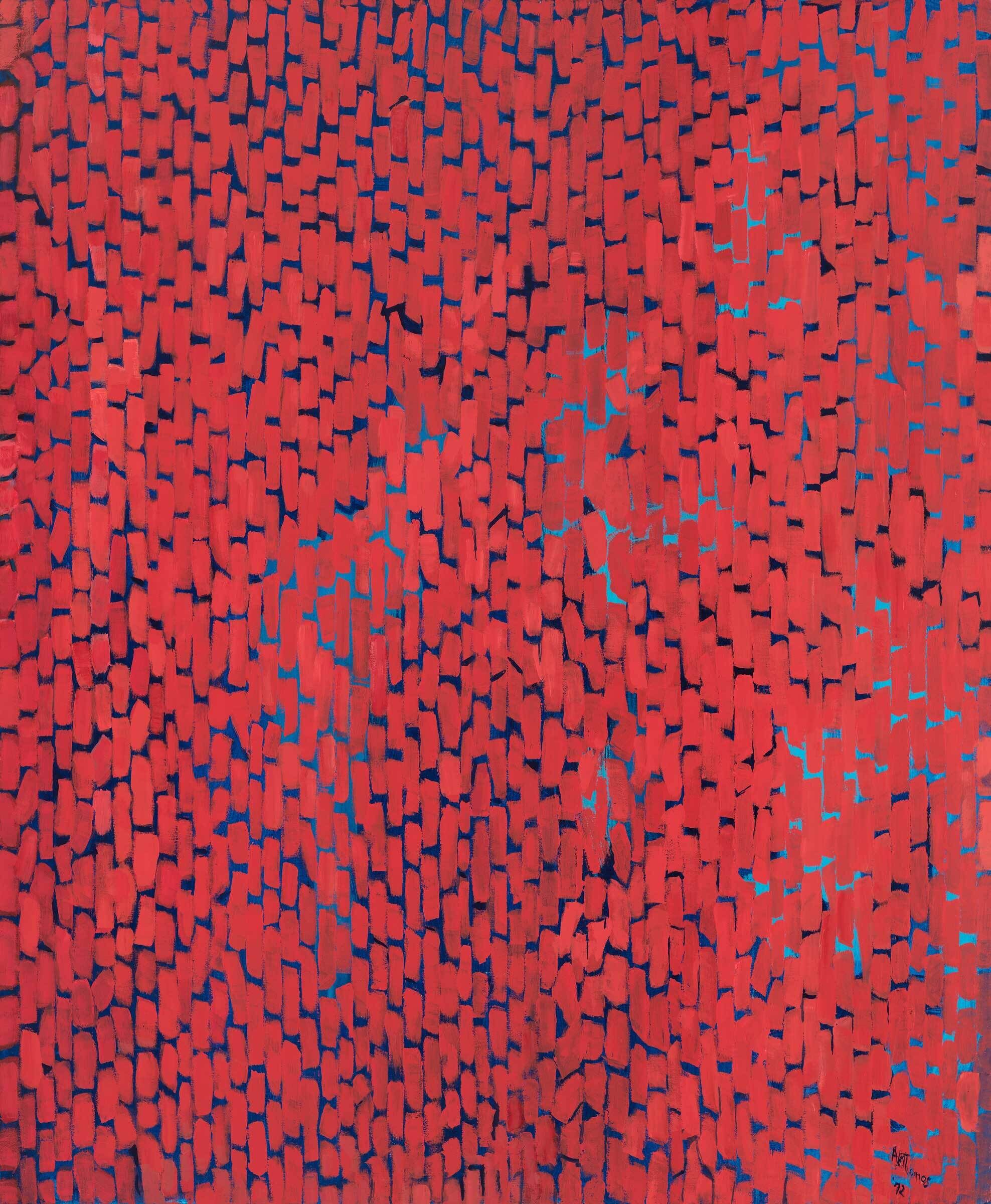

Georgia O’Keeffe used her art to record emotional and sensory experiences, especially her responses to the rhythms and forms of the natural world. Raised on a dairy farm in rural Wisconsin, O’Keeffe attended the Art Students League and Teacher’s College at Columbia University in New York, where she trained to be an art teacher. She first came to the attention of the New York art world in the spring of 1916 when her radically abstract charcoal drawings were exhibited at Alfred Stieglitz’s pioneering 291 gallery. The artist described the simple, organic motifs of these works, including the spiral form that appears in No. 8 – Special (Drawing No. 8), as vehicles for conveying feelings she could not put into words. “Abstraction,” she remarked, “is often the most definite form for the intangible thing in myself that I can only clarify in paint.” As O’Keeffe expanded her repertoire in 1918 to include oil, she retained the fluid space and curvilinear motifs of her early charcoals. Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, for example, uses gently feathered brushwork and a vibrant palette to evoke the undulating rhythms of nature. Such an approach marked a departure from the fractured geometric language, inspired by European Cubism, which dominated vanguard American painting in the early twentieth century. Yet as the painting’s title suggests, O’Keeffe—like many of her modernist colleagues in the United States and Europe—was interested in exploring the correlation between abstract painting and music as nonverbal forms of emotional expression.

Throughout her long and prolific career, O’Keeffe continued to produce highly abstract works, such as the geometric Black and White, which she mysteriously described as “a message to a friend.” By the mid-1920s, however, she also began painting images with recognizable subjects, earning particular acclaim for her depictions of flowers. In works such as The White Calico Flower, O’Keeffe eschewed the traditional figure-ground format of still-life painting, opting instead to dramatically enlarge her botanical subjects so that they oscillate between abstraction and representation. The subject of this painting was not a live specimen, but a cloth flower used in Southwestern mourning rituals. O’Keeffe’s use of cropping and magnification in this and other flower compositions reflected her interest in modernist photographic techniques, which she encountered through her close relationships with photographers Paul Strand and Stieglitz, whom she married in 1924. Filling the entire frame of the canvas, O’Keeffe’s flowers are neither diminutive nor ephemeral—rather, they are objects of commanding monumentality. Although critics often discussed the flower paintings in sexual terms, O’Keeffe rejected these interpretations, suggesting instead that they were intended to surprise viewers and call attention to the overlooked details of the natural world.

In 1929, O’Keeffe began spending parts of each year working in New Mexico, to which she moved permanently in 1949. She drew inspiration from the stark desert landscape as well as the organic objects she collected there, including animal bones, stones, and feathers. The floating animal skull that appears at the center of Summer Days was a motif that O’Keeffe introduced in 1931, when she began painting bones that she had brought back east from her New Mexico sojourns. The desiccated, sun-bleached skull is paired here with—and yet stands in stark contrast to—a group of vibrantly blooming desert wildflowers. Hovering in the clouds over a distant line of red clay hills, the skull and flowers present a distinctive iconography of the American Southwest. And at the same time, with its distorted scale and enigmatic symbols of life and death, the painting demonstrates O’Keeffe’s awareness of the incongruous aesthetic juxtapositions employed by Surrealist artists working in Europe and the United States during the same period.

Dana Miller and Adam D. Weinberg, Handbook of the Collection (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2015), 286–288.

Introduction

Georgia Totto O'Keeffe (November 15, 1887 – March 6, 1986) was an American modernist painter and draftswoman whose career spanned seven decades and whose work remained largely independent of major art movements. Called the "Mother of American modernism", O'Keeffe gained international recognition for her paintings of natural forms, particularly flowers, hills and desert-inspired landscapes, which were often drawn from and related to places and environments in which she lived.

From 1905, when O'Keeffe began her studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, until about 1920, she studied art or earned money as a commercial illustrator or teacher to pay for further education. Influenced by Arthur Wesley Dow, she began to develop her unique style through her watercolors during her studies at the University of Virginia and, more dramatically, through the charcoal drawings she produced in 1915 that marked her move toward abstraction. Alfred Stieglitz, an art dealer and photographer, held an exhibit of her works in 1916. Over the next couple of years, she taught and continued her studies at the Teachers College, Columbia University.

She moved to New York in June 1918 at Stieglitz's request and began working seriously as an artist. They developed a professional and personal relationship that led to their marriage on December 11, 1924. O'Keeffe created many forms of abstract art, including close-ups of flowers, such as the Red Canna paintings, that many found to represent vulvas, though O'Keeffe consistently denied that intention. The imputation of the depiction of women's sexuality was also fueled by explicit and sensuous photographs of O'Keeffe that Stieglitz had taken and exhibited.

O'Keeffe and Stieglitz lived together in New York until 1929, when O'Keeffe began spending part of the year in the Southwest, which served as inspiration for her paintings of New Mexico landscapes and images of animal skulls, such as Cow's Skull: Red, White, and Blue (1931) and Summer Days (1936). She moved to New Mexico in 1949, three years after Stieglitz's death in 1946, where she lived for the next 40 years at her home and studio or Ghost Ranch summer home in Abiquiú, and in the last years of her life, in Santa Fe. In 2014, O'Keeffe's 1932 painting Jimson Weed/White Flower No. 1 sold for $44,405,000—at the time, by far the largest price paid for any painting by a female artist. Her works are in the collections of several museums, and following her death, the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum was established in Santa Fe.

Wikidata identifier

Q46408

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed February 14, 2026.

Introduction

She was born to Francis Calyxtus O'Keeffe and Ida Totto O'Keeffe on a large dairy farm in Wisconsin. She was an American painter, trained in Chicago and New York where she came into contact with modern developments in art, as well as non-western traditions and photography. Her husband, the photographer Alfred Steiglitz showed her work yearly until his death in 1946. O'Keeffe is best known for extreme close-up images of abstracted natural forms, such as flowers, animal bones, clouds, and landscapes. From 1929 she spent most of her summers painting in New Mexico, moving there permanently in 1949. In 1971, she learned to be a hand-potter. Comment on works: Landscapes

Country of birth

United States

Roles

Artist, lecturer, painter

ULAN identifier

500018666

Names

Georgia O'Keeffe, Georgia O'Keefe, Georgia O' Keeffe, O'Keeffe, Georgia Totto O'Keeffe, Mrs. Alfred Stieglitz, Georgia Stieglitz, Georgia O'Keeffe Stieglitz

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License. Accessed February 14, 2026.