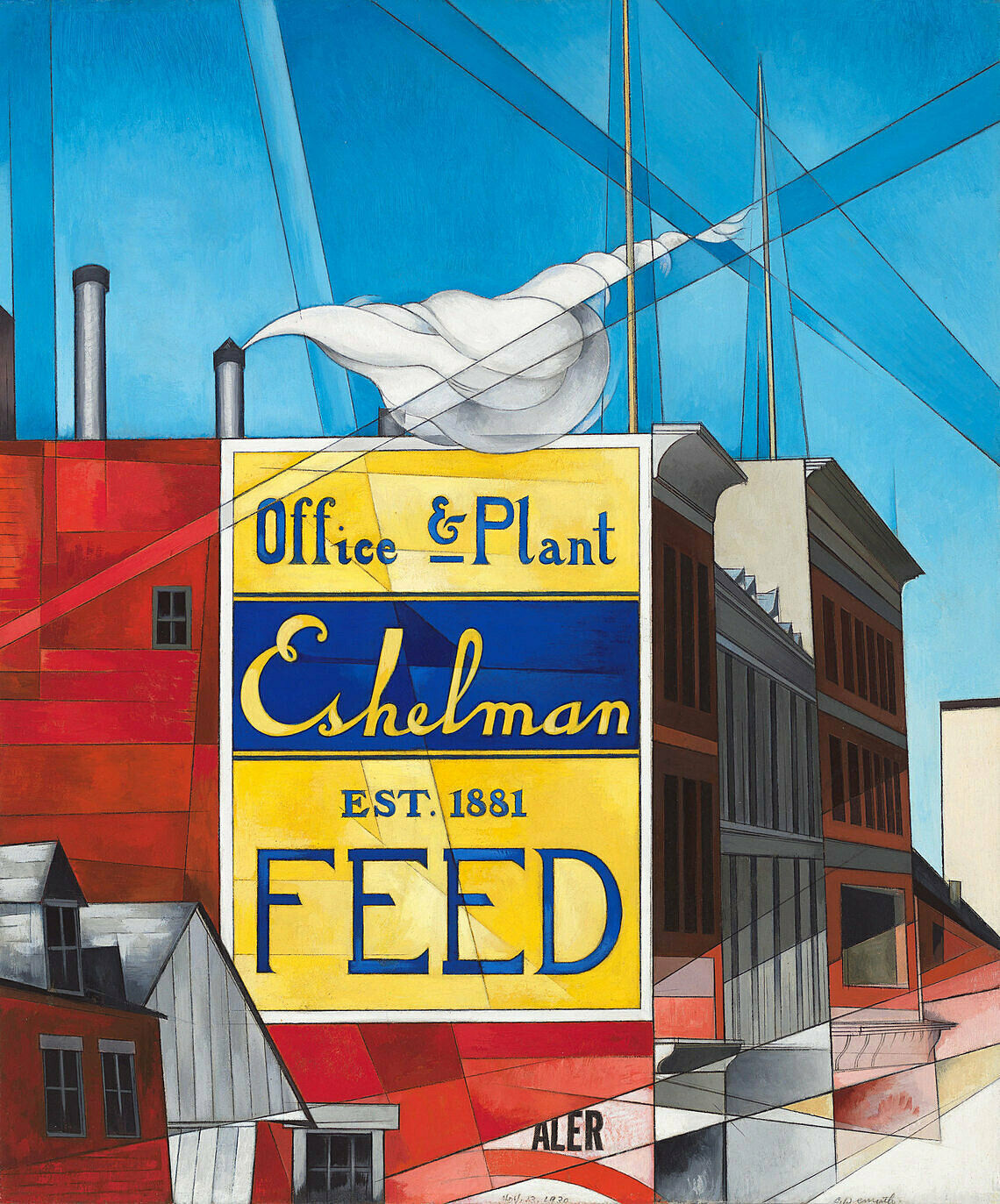

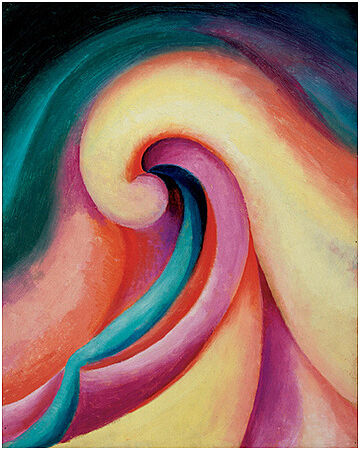

For many vanguard artists in the early twentieth century, music offered a model for expressing nonverbal emotional states and sensations. Georgia O'Keeffe was fascinated with what she called "the idea that music could be translated into something for the eye," but her references to music in the titles of her paintings derived equally from her belief that visual art, like music, could convey powerful emotions independent of representational subject matter. In Music—Pink and Blue II, the swelling, undulating forms imply a connection between the visual and the aural, while also suggesting the rhythms and harmonies that O’Keeffe perceived in nature.

Visual description

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Music, Pink and Blue No. 2 (1918) is an oil painting on canvas. It measures 35 inches in height and 29 15/16 inches in width. It measures 88.9 centimeters in height and 76 centimeters in width.

This is an abstract painting. The colors are pale and light with an emphasis on pinks and blues. Emerging from the bottom of the painting, near the right corner, vertically slanting to our left is a blue tongue shape. Softly curved, swaying to our left, the color of aqua tinted water—this shape can be seen as a hole or a void. It is surrounded by an outer ribbon of white space that is tinged with tones of mint green and pale pink. The way this outer shape folds over the blue area intensifies the sense that we are gazing into the opening of an interior space. The curved white outer area is rimmed with a thin edge of pink and red—the colors bear a relationship to blood and flesh. Beyond this area are petal forms of pale violet outlined in red. These petals rest upon each other and morph into soft hills on our left. Behind these lavender petals is a crack between folds of pink and peach that rise to the top of the painting—a little left of center. Surrounding these folds and the soft fluttering petals that surround the white ribbon that homes the blue void from which we started this description is a background of light blue that turns to a pink violet in some areas and into light ripples in the upper right corner. O’Keeffe uses thin translucent washes of oil paint to create her seductive abstraction.

Not on view

Date

1918

Classification

Paintings

Medium

Oil on canvas

Dimensions

Overall: 35 × 29 15/16 in. (88.9 × 76 cm)

Accession number

91.90

Credit line

Gift of Emily Fisher Landau in honor of Tom Armstrong

Rights and reproductions

© Georgia O'Keeffe Museum / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Videos

-

Georgia O'Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2 | Video in American Sign Language -

Georgia O'Keeffe: Abstraction

Audio

-

0:00

Verbal Description: Georgia O'Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2

0:00

Georgia O’Keeffe’s Music, Pink and Blue No. 2 (1918) is an oil painting on canvas. It measures 35 inches in height and 29 15/16 inches in width. It measures 88.9 centimeters in height and 76 centimeters in width.

This is an abstract painting. The colors are pale and light with an emphasis on pinks and blues. Emerging from the bottom of the painting, near the right corner, vertically slanting to our left is a blue tongue shape. Softly curved, swaying to our left, the color of aqua tinted water—this shape can be seen as a hole or a void. It is surrounded by an outer ribbon of white space that is tinged with tones of mint green and pale pink. The way this outer shape folds over the blue area intensifies the sense that we are gazing into the opening of an interior space. The curved white outer area is rimmed with a thin edge of pink and red—the colors bear a relationship to blood and flesh. Beyond this area are petal forms of pale violet outlined in red. These petals rest upon each other and morph into soft hills on our left. Behind these lavender petals is a crack between folds of pink and peach that rise to the top of the painting—a little left of center. Surrounding these folds and the soft fluttering petals that surround the white ribbon that homes the blue void from which we started this description is a background of light blue that turns to a pink violet in some areas and into light ripples in the upper right corner. O’Keeffe uses thin translucent washes of oil paint to create her seductive abstraction.

Verbal Description: Georgia O'Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2

In The Whitney's Collection: Selections from 1900 to 1965 and At the Dawn of a New Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism

-

0:00

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue

0:00

Narrator: With its soft, petal-like folds, this painting by Georgia O’Keeffe seems floral—but it doesn’t depict any particular flower. It’s an abstraction that the artist has rooted in natural form.

Wanda Corn: One of the features of this painting is the beautiful sense of movement that you have where nothing is static in the picture.

Narrator: Wanda Corn is a historian of American art.

Wanda Corn: You feel as if every form is breathing and opening up to the form next to it. This was a very important concept of keeping forms in the stage of becoming. This was something that artists tried to do in their abstractions in the late teens, and O'Keeffe is responding to that notion of time not stopping, of there being a constant movement in the work itself.

When these paintings were seen for the first time, very often critics would see in them female forms. They would see in it allusions to the womb or to female reproductive organs. They would see womanly colors such as the pinks, the blues and the lavender. And it would be read as a painting that was one that could only have been made by a female intelligence.

This was a common way of talking about O'Keeffe's paintings in her early years. It was one that was prompted by her husband Alfred Stieglitz who liked to read in O'Keeffe's paintings an expression of the sort of eternal female.

O'Keeffe herself felt as if that was more a comment on the critic than what she intended. She often would say it's about natural forms, but it's not to be tied to exclusively the female body. And she would have you rather see in a work like this a kind of slipperiness of form where you can't tie it to any one thing, be it a flower or be it a female body or be it a landscape. But that it has poetic allusions to all of those.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue

In At the Dawn of a New Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism

-

0:00

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

0:00

Narrador: Georgia O'Keeffe se inspiró en lo que veía en la naturaleza. Incluso en una pintura abstracta como esta, la artista usó líneas curvadas y fluidas, y colores brillantes que pudieran sugerir algo natural, como una flor o una concha.

En muchas de sus pinturas, O’Keeffe dirige tu mirada desde la orilla hasta el centro. Aquí se mueve desde un arco ondulante y pálido hasta un azul profundo en el centro.

¿Puedes imaginarte dentro de esta pintura? ¿Te acurrucarías en el centro? ¿Te deslizarías por la orilla exterior? ¿O te envolverías con los colores como una pañoleta?

O’Keeffe quería que sus pinturas expresaran sentimientos para los que no tenía palabras. Llamó a esta pintura Music, Pink and Blue No. 2. Aunque sea instrumental y no tenga letra, la música puede expresar sentimientos. O’Keeffe pensó que las pinturas podían provocar lo mismo, sin necesidad de usar imágenes identificables. Podían comunicar de otras maneras. ¿Puedes ver los ritmos en esta pintura?

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

In Where We Are (Kids, Spanish)

-

0:00

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

0:00

Wanda Corn: Cuando estas pinturas fueron exhibidas por primera vez, los críticos solían descubrir formas femeninas en ellas. Veían alusiones al útero o a los órganos reproductivos femeninos. Veían colores femeninos, como rosas, azules y lavandas. Y se interpretaron como pinturas que solo podían estar realizadas por una inteligencia femenina.

Esta fue una manera común de hablar acerca de las pinturas tempranas de O'Keeffe. Y fue causada por su esposo Alfred Stieglitz, que gustaba de leer en las pinturas de O'Keeffe una expresión del eterno femenino.

O'Keeffe misma sintió que ese era más un comentario sobre la crítica que sobre lo que ella había pretendido. Con frecuencia decía que su pintura era acerca de formas naturales, pero que no estaban ligadas exclusivamente al cuerpo femenino. Y ella hubiera preferido que el observador viera en una obra como esta una especie de deslizamiento de la forma que no se puede vincular a ninguna cosa en particular, bien sea una flor o un cuerpo femenino o un paisaje, sino que guarda alusiones poéticas con todos los anteriores.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

In Where We Are (Spanish)

-

0:00

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

0:00

Narrador: Con sus pliegues suaves como pétalos, esta pintura de Georgia O’Keeffe pareciera ser floral, pero no representa ninguna flor en particular. Es una abstracción a la cual la artista dio una forma natural, orgánica. En 1918, cuando O’Keeffe pintó este lienzo, el arte abstracto era muy nuevo y radical: las primeras pinturas totalmente abstractas se habían realizado apenas ocho años antes. Sin embargo, el título que O’Keeffe dio a esta obra —Music Pink and Blue— sugiere que las ideas detrás del arte abstracto ya formaban parte de la cultura occidental. Hacía ya mucho tiempo que se entendía la música como un arte expresivo, aunque careciera de narración o contenido representacional. Al equiparar su pintura con la música, O’Keeffe sugiere que la forma y el color puros también tienen un poder expresivo.

Wanda Corn: Uno de los rasgos de esta pintura es la hermosa sensación de movimiento que se tiene cuando nada es estático en la imagen.

Narrador: Wanda Corn es historiadora de arte estadounidense.

Wanda Corn: El observador siente que cada forma respira y se abre a la forma siguiente. Este es un concepto muy importante: el de mantener formas en un estado potencial. Era algo que los artistas intentaban plasmar en sus abstracciones de fines de la década de 1910, y aquí O'Keeffe responde a ese concepto del tiempo que no se detiene, al del movimiento constante en la propia obra.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

In Where We Are (Spanish)

-

0:00

Georgia O'Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

0:00

Narrator: Georgia O'Keeffe was inspired by things she saw in nature. Even in an abstract painting like this one, she used curvy, flowing lines and brilliant colors that might suggest something natural, like a blooming flower or a shell.

In many of her paintings, O’Keeffe draws your eye from the edge to the center. Here, it moves from a pale billowy arc into deep blue.

Can you picture yourself in this painting? Would you cocoon yourself in the center? Slip along the outer edge? Or wrap the colors around you like a scarf?

O’Keeffe wanted her paintings to express feelings that she didn’t have words for. She called this painting Music, Pink and Blue No. 2. Music can express feelings even when it’s instrumental, and doesn’t have lyrics. O’Keeffe thought paintings could be the same way—they didn’t need to have identifiable images. They could communicate in other ways. Can you see the rhythms in this painting?

Georgia O'Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

In The Whitney's Collection: Selections from 1900 to 1965 and Where We Are (Kids)

-

0:00

Georgia O'Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

0:00

Wanda Corn: When these paintings were seen for the first time, very often critics would see in them female forms. They would see in it allusions to the womb or to female reproductive organs. They would see womanly colors such as the pinks, the blues and the lavender. And it would be read as a painting that was one that could only have been made by a female intelligence.

This was a common way of talking about O'Keeffe's paintings in her early years. It was one that was prompted by her husband Alfred Stieglitz who liked to read in O'Keeffe's paintings an expression of the sort of eternal female.

O'Keeffe herself felt as if that was more a comment on the critic than what she intended. She often would say it's about natural forms, but it's not to be tied to exclusively the female body. And she would have you rather see in a work like this a kind of slipperiness of form where you can't tie it to any one thing, be it a flower or be it a female body or be it a landscape. But that it has poetic allusions to all of those.

Georgia O'Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No. 2, 1918

In The Whitney's Collection: Selections from 1900 to 1965 and Where We Are

-

0:00

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No 2, 1918

0:00

Narrator: With its soft, petal-like folds, this painting by Georgia O’Keeffe seems floral—but it doesn’t depict any particular flower. It’s an abstraction that the artist has rooted in natural form. When O’Keeffe painted this canvas in 1918, abstract art was very new and radical: the first fully abstract paintings had been made only eight years earlier. But the title that O’Keeffe has given this work—Music Pink and Blue—hints that the ideas behind abstract art were already part of western culture. It had long been understood that music was expressive—even when it had no narrative or representational content. By likening her painting to music, O’Keeffe suggests that pure form and color can have expressive power too.

Wanda Corn: One of the features of this painting is the beautiful sense of movement that you have where nothing is static in the picture.

Narrator: Wanda Corn is a historian of American Art.

Wanda Corn: You feel as if every form is breathing and opening up to the form next to it. This was a very important concept of keeping forms in the stage of becoming. This was something that artists tried to do in their abstractions in the late '10s, and O'Keeffe is responding to that notion of time not stopping, of there being a constant movement in the work itself.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Music, Pink and Blue No 2, 1918

Exhibitions

-

At the Dawn of a New Age: Early Twentieth-Century American Modernism

May 7, 2022–Feb 26, 2023

-

The Whitney’s Collection: Selections from 1900 to 1965

June 28, 2019–May 1, 2025

-

Where We Are: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1900–1960

Apr 28, 2017–June 2, 2019

-

America Is Hard to See

May 1–Sept 27, 2015

-

American Legends: From Calder to O’Keeffe

Dec 22, 2012–June 29, 2014

-

Georgia O’Keeffe: Abstraction

Sept 17, 2009–Jan 17, 2010

-

The Whitney’s Collection

Jan 30, 2008–Jan 3, 2010

-

Highlights from the Permanent Collection: From Hopper to Mid-Century

Feb 26, 2000–May 21, 2006

-

Permanent Collection

Apr 4, 1998–Mar 28, 1999

-

An American Story

Mar 20–Sept 29, 1996