Claes Oldenburg

1929–2022

Claes Oldenburg has famously written that he is “for an art that . . . twists and extends and accumulates and spits and drips, and is heavy and coarse and blunt and sweet and stupid as life itself.” In this commitment to imbue his art with the energy of “life itself,” Oldenburg has frequently turned to commonplace objects as his subject matter, transforming them through unexpected contexts, materials, or scale shifts. In late 1961, he temporarily turned a storefront on Manhattan’s Lower East Side into a hybrid studio, gallery, and market, making and selling his sculptural versions of familiar products from nearby businesses, such as food or clothing, and calling the project The Store. Produced by molding plaster-dipped muslin over wire and applying bright enamel paint to the mottled surfaces, the sculptures from The Store are expressionistic interpretations rather than slick, realistic facsimiles. Works such as Braselette imply the human body as much as the commodity. Oldenburg has explained, “I never make representations of bodies, but of things that relate to bodies so that the body sensation is passed along to the spectator either literally or by suggestion.”

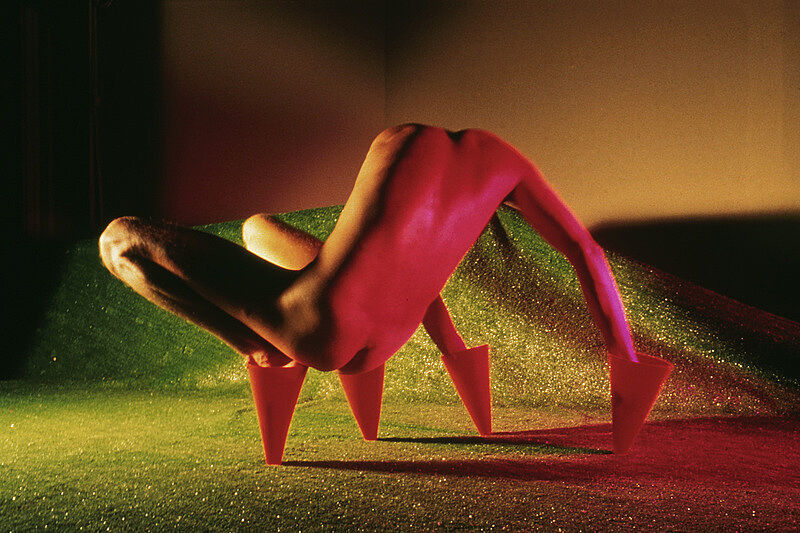

During this period, Oldenburg was also creating pioneering theatrical performance-art pieces known as Happenings. The elaborate costumes, props, and sets crafted for these performances led to experiments with soft, sewn sculptures. Though the earliest works were in canvas, he discovered that vinyl, an industrial material that had found new upholstery applications in postwar America, provided the desired contrast between hard and soft, the manufactured and the handmade. Giant BLT (Bacon, Lettuce, and Tomato Sandwich), among his early vinyl works, extended Oldenburg’s interest in performance to the object itself: comprised of nineteen individual pieces in varying shapes and textures, it must be assembled like a sandwich to be displayed, provocatively pierced with a wooden toothpick. Soft Toilet, produced as part of a group of sculptures of bathroom fixtures (outrageous subject matter at the time), similarly has a subtle performative element. Stuffed with kapok fibers, the sculpture is molded as much by the exterior sewn elements as by gravity (which Oldenburg has called his “favorite form creator”) when the pliable vinyl sags and settles over time. Porcelain is thus imagined as a slack, flesh-like substance.

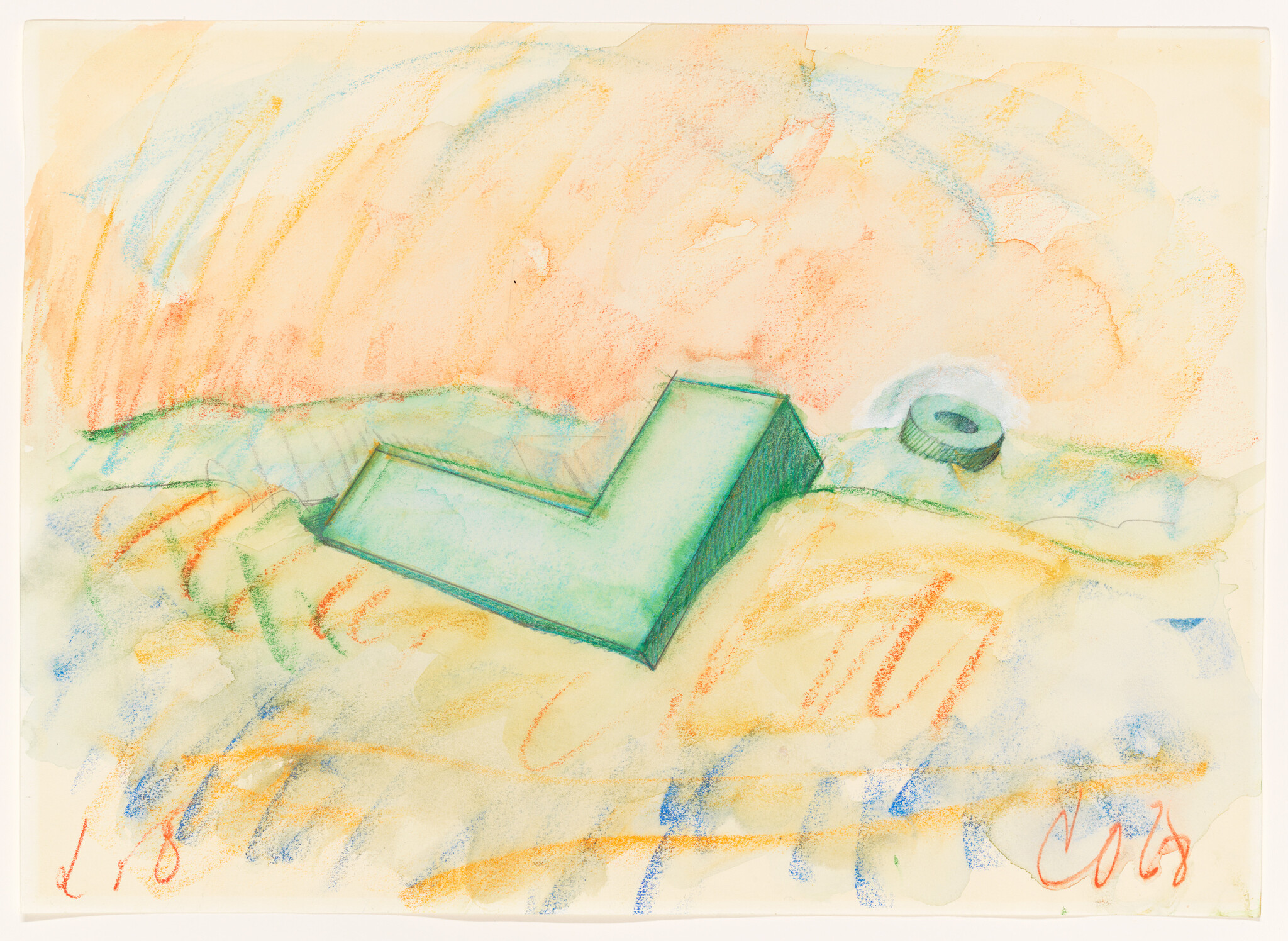

The sandwich and the toilet are defiantly nontraditional artistic subjects. In 1965, Oldenburg began a drawing series that imagined similarly mundane objects as huge public sculptures sited in cities around the globe. In Proposed Colossal Monument for Central Park North, N.Y.C.—Teddy Bear, the playful toy masks a political edge; the towering stuffed bear would confront touristic park-goers looking north with a fixed stare that Oldenburg imagined as a subtle rebuke on behalf of Harlem’s disenfranchised residents. Though the Proposed Colossal Monument series began as a speculative exercise, Oldenburg became increasingly interested in realizing large-scale projects. In collaboration with Coosje van Bruggen, with whom he worked from 1976 until her death in 2009, he developed site-specific works all over the world referred to as the Large-Scale Projects. Oldenburg and van Bruggen’s drawing Soft Shuttlecocks, Falling, Number Two, grew out of their site-specific installation on the lawn of Kansas City’s Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art. While the lawn reminded the artists of a tennis court, they selected the shuttlecock rather than a tennis ball because the feathers related to the museum’s extensive collection of Native American feathered headdresses, and because the contrasting features of the shuttlecock’s cork and cone provided a wonderfully expressive form. In this drawing the artists imagine two floating shuttlecocks circling each other gracefully in a kind of pas de deux.

Dana Miller and Adam D. Weinberg, Handbook of the Collection (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2015), 289–291.

Introduction

Claes Oldenburg (January 28, 1929 – July 18, 2022) was a Swedish-born American sculptor best known for his public art installations, typically featuring large replicas of everyday objects. Another theme in his work is soft sculpture versions of everyday objects. Many of his works were made in collaboration with his wife, Coosje van Bruggen, who died in 2009; they had been married for 32 years. Oldenburg lived and worked in New York City.

Wikidata identifier

Q156731

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed January 31, 2026.

Introduction

Claes Oldenburg studied literature and art history at Yale University and the Art Institute of Chicago. He quickly became involved in performance art after moving to New York and meeting many performance artists. By 1959, he had created drawings and collages of common objects and renderings of grotesque human figures. He created The Store in his studio, a performance space that re-created a neighborhood of shops that displayed goods that were made of plaster. He emerged as a leading Pop artist, combining consumer culture into his own sculptures. Oldenburg married artist Coosje van Bruggen in 1977. The two collaborated on many large-scale projects together and with architect Frank O. Gehry in the mid-1970s and early 1990s.

Country of birth

Sweden

Roles

Artist, painter, performance artist, sculptor, writer

ULAN identifier

500029735

Names

Claes Oldenburg, Claes Thure Oldenburg, Ḳlaʼes Oldenberg

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License. Accessed January 31, 2026.