David Wojnarowicz

1954–1992

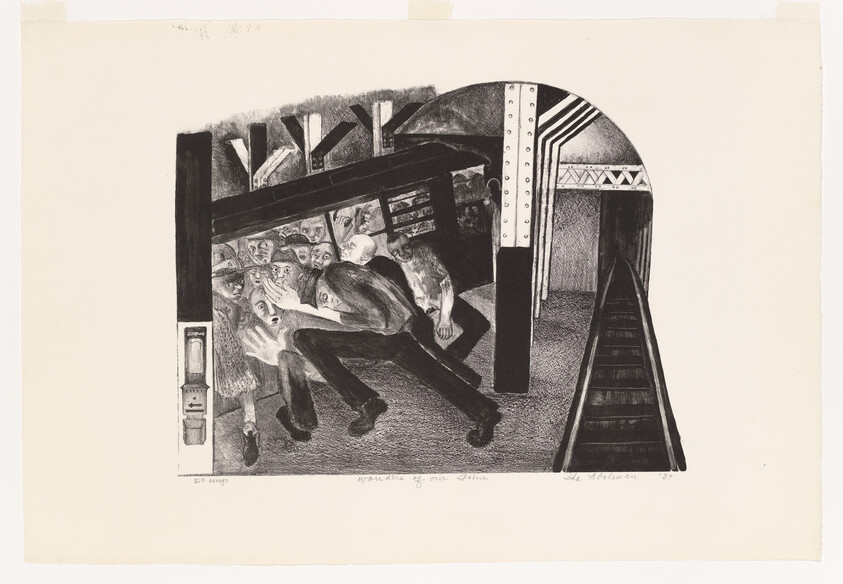

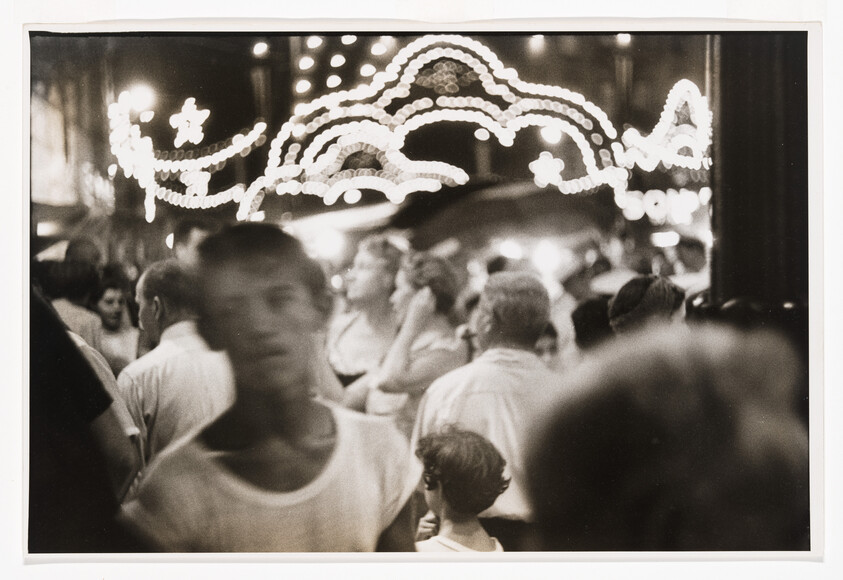

In an artistic practice spanning photography, painting, collage, sculpture, film, and writing, David Wojnarowicz distilled his moral fury into a powerful weapon amid the political and social turbulence of the 1980s—addressing in particular the devastation of the AIDS epidemic, homophobic politicians and policy, and the institutionalized apathy and loss of spirituality he saw in American society. His work was shaped and propelled by the violence and marginalization he had experienced: as a child, growing up in suburban New Jersey with an abusive, alcoholic father; as a teenager hustling on New York’s streets; and, later, as a gay man living with (and eventually dying from) AIDS. He emerged in the early 1980s as a leading figure of the loosely defined East Village scene of galleries, clubs, and alternative art spaces, and collaborated widely with his peers, including Kiki Smith and Peter Hujar, who was Wojnarowicz’s close friend and mentor until Hujar’s death in 1987.

In paintings and sculptures from the mid-1980s Wojnarowicz developed a visual language built upon the principle of collage, using found posters and images, maps, stencils, and paint to build up layered, often cacophonous surfaces. Fear of Monkeys/Evolution combines imagery drawn from an intricate, personal web of symbols to which he would frequently return: a monkey (symbol of the possible origin of the HIV virus), a clock face without hands (a reference to mortality and the loss of time), and sperm shapes cut out from a map (signifying desire, reproduction, and/or contagion), among other elements arranged across torn sheets of music. Often recalling states of reverie or dreaming, his paintings present an anxious, teeming vision, “like fragmented mirrors of what I perceive to be the world.”

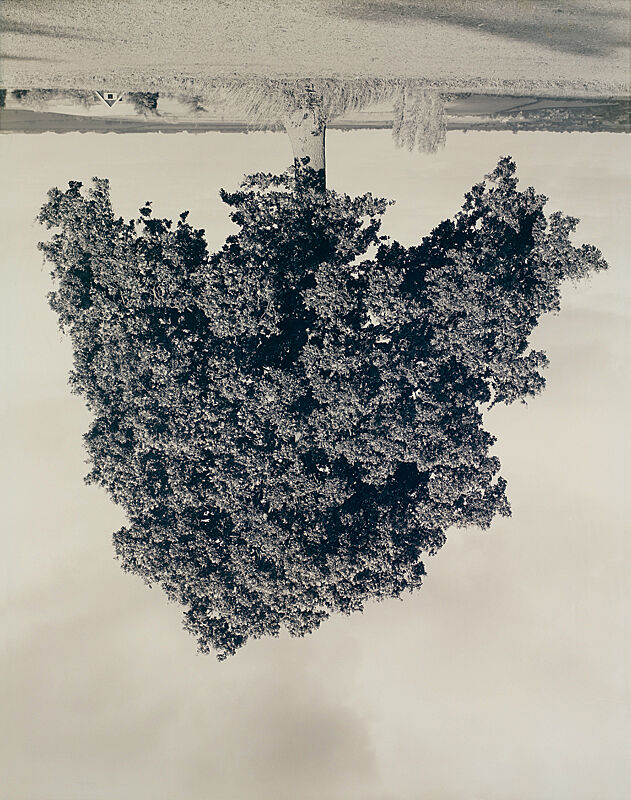

In the late 1980s Wojnarowicz increasingly moved away from painting and toward photography, a medium he had used since the 1970s. Untitled, a triptych of images he made of Hujar just after his death, presents vignettes of his friend and mentor’s body—a haunting document of loss, tenderness, and intimacy, and an attempt to reverse the invisibility of AIDS-related deaths. “History is made and preserved by and for particular classes of people,” he wrote. “A camera in some hands can preserve an alternate history.”

Wojnarowicz’s writings were another means of telling such alternate stories; like much of his work, they offer reflexive accounts of desire, fear, and anger, narratives of experience marked by “the sensation of being an observer of my own life as it occurs.” He often incorporated his writings into works that hinge on the relation of text and image. Untitled (One Day This Kid . . . ) relies on a concise formal economy: a grainy image of Wojnarowicz as a child, set within a text that outlines what he saw the future holding for a queer person—loss of political rights, dispossession, and abuse. An icon of activism and queer identity, the work telegraphs Wojnarowicz’s uncompromising commitment to claiming visibility within a society that had rejected him.

Dana Miller and Adam D. Weinberg, Handbook of the Collection (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2015), 414–415.

Introduction

David Michael Wojnarowicz ( VOY-nə-ROH-vitch; September 14, 1954 – July 22, 1992) was an American painter, photographer, writer, filmmaker, performance artist, songwriter/recording artist, and AIDS activist prominent in the East Village art scene. He incorporated personal narratives influenced by his struggle with AIDS as well as his political activism in his art until his death from the disease in 1992.

Wikidata identifier

Q952233

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed February 12, 2026.

Country of birth

United States

Roles

Artist, collagist, mixed-media artist, painter, performance artist, photographer, sculptor, writer

ULAN identifier

500081953

Names

David Wojnarowicz

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License. Accessed February 12, 2026.