David Smith

1906–1965

David Smith, one of the most prominent and celebrated American sculptors of the twentieth century, is known primarily for the welded steel abstractions he executed throughout his nearly four- decade-long career. Although he trained as a painter in the late 1920s, Smith also produced numerous drawings and photographs, moving fluidly between two and three dimensions, and between positive and negative space.

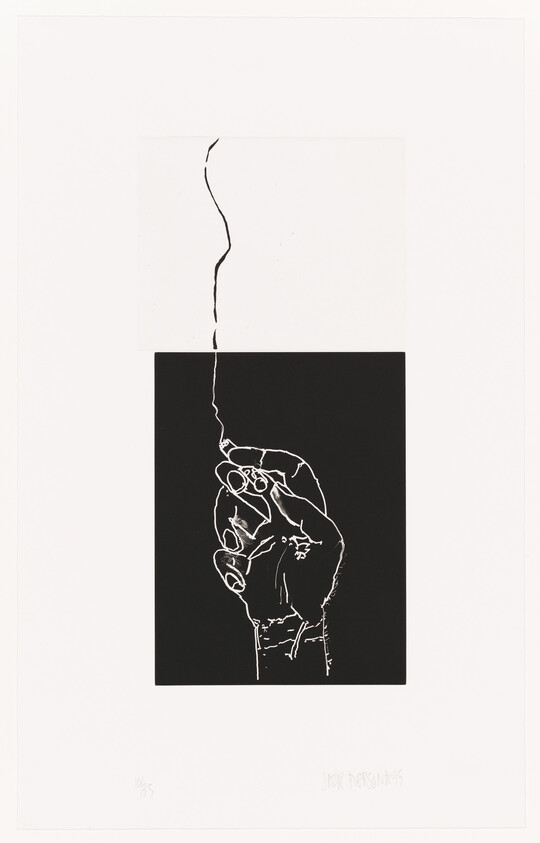

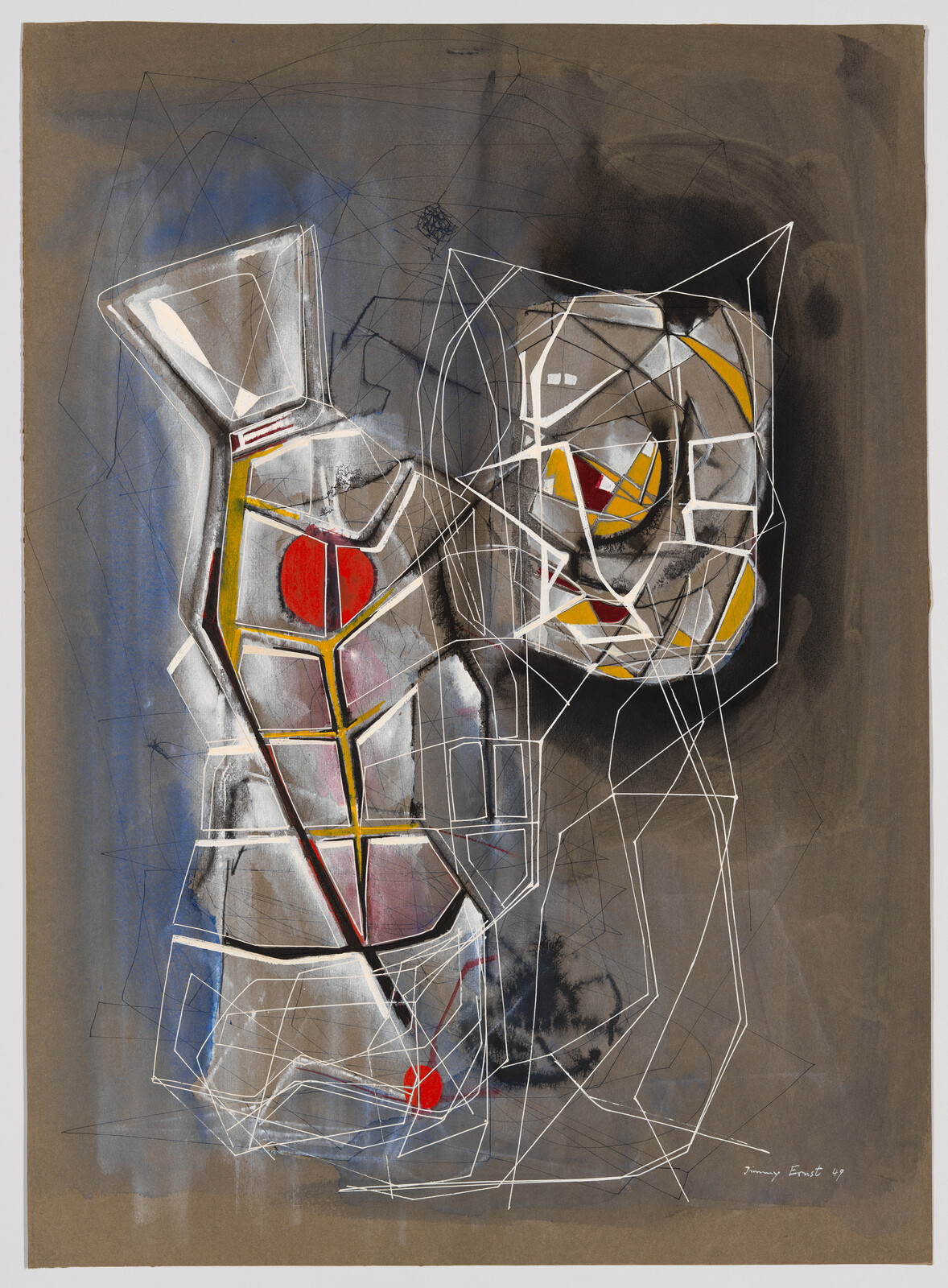

Smith configured his first welded metal sculpture in 1933 after seeing reproductions of constructions by Pablo Picasso and Julio González from the late 1920s. For such works, a welder, using either a torch or an electrical current, fuses metal pieces with an additional steel rod. Both the modern material and the modern process appealed to Smith, who saw the late-nineteenth-century invention as freed from the weight of art history. He derived Hudson River Landscape, a lyrical, open-frame sculpture, from sketches made while riding the train between his home in Bolton Landing, in upstate New York, and New York, in particular the seventy-five-mile stretch between Albany and Poughkeepsie. “Later,” Smith recalled, “while drawing, I shook a quart bottle of India ink and it flew over my hand. It looked like my river landscape. I placed my hand on paper. From the image that remained, I travelled with the landscape, drawing other landscapes and their objects, with additions, deductions, directives, which flashed unrecognized into the drawing, elements of which are in the sculpture. Is my sculpture the Hudson River? Or is it the travel and the vision? Or does it matter? The sculpture exists on its own; it is an entity.” Smith’s sculptural process, often described as “drawing in space,” relates closely to his works made on paper. These he executed nearly every day using ink, tempera, and oil. The bright red color featured in Eng No. 6 echoes the artist’s desire to merge painting and sculpture, which he explored in polychrome three-dimensional works. Indeed, he described his drawings as “studies for sculpture, sometimes what sculpture is, sometimes what sculpture can never be.”

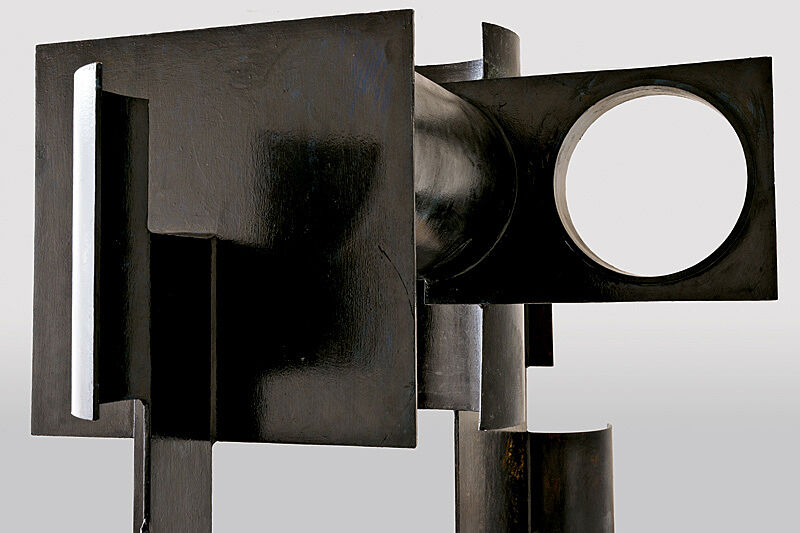

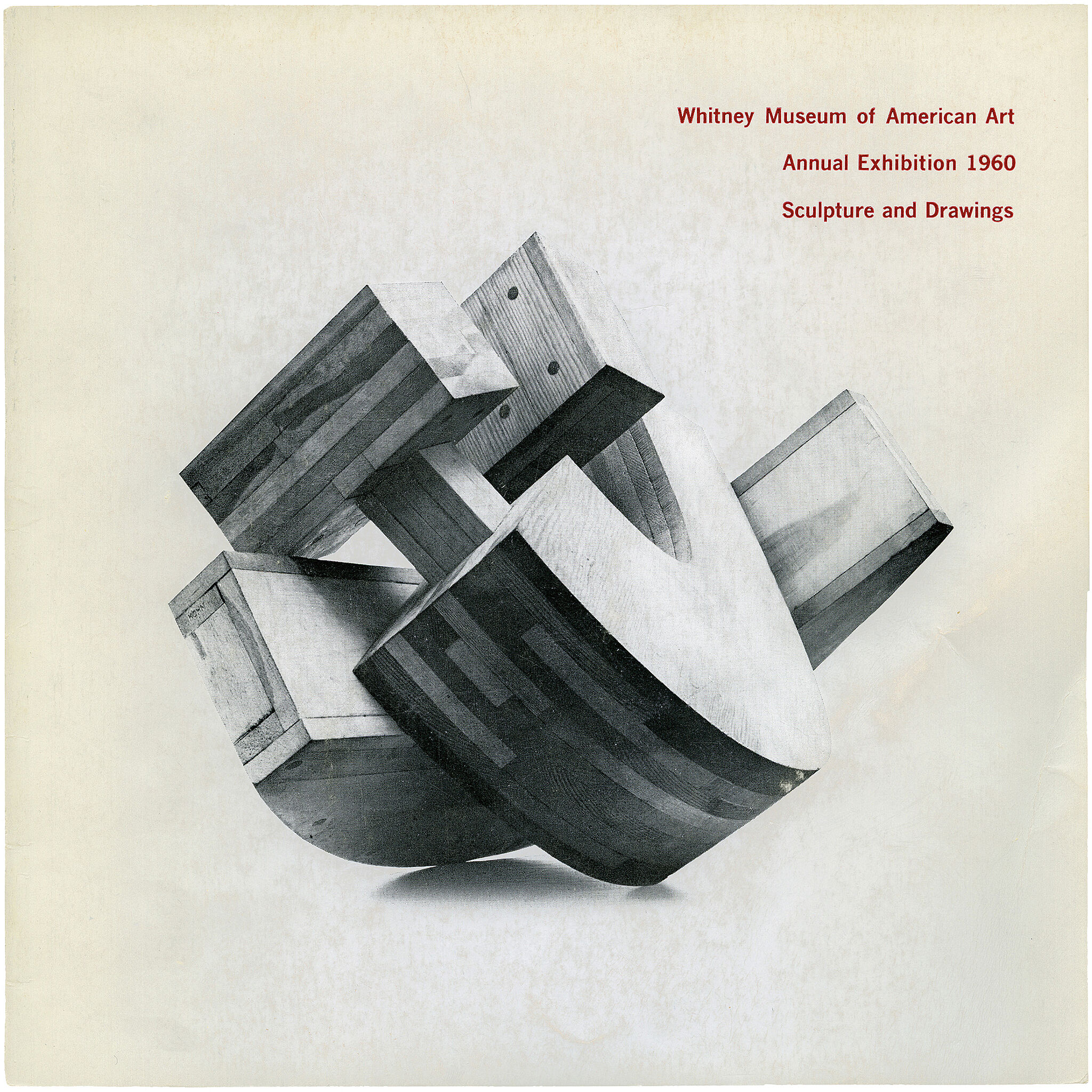

Smith began his last series, titled Cubi, in 1961. He configured this group of twenty-eight monumental stainless steel sculptures from prefabricated, hollow geometric components. Cubi XXI aggregates cubic, rectangular, cylindrical, and tubular elements. The Cubi seem at once balanced and unstable; they convey a sense of action even in their solidity. This is due in large part to their burnished surfaces, which Smith achieved using a circular sander. His sweeping, arching movements produced a brushstroke effect on the polished surface. When positioned outside, the Cubi catch and reflect changing light conditions, reminding the viewer that forms interact with, depend upon, and alter the space around them.

Introduction

Roland David Smith (March 9, 1906 – May 23, 1965) was an American abstract expressionist sculptor and painter known for creating large steel abstract geometric sculptures.

Born in Decatur, Indiana, Smith initially pursued painting, receiving training at the Art Students League in New York from 1926 to 1930. However, his artistic journey took a transformative turn in the early 1930s when he shifted his focus to sculpture.

In the early phase of his career, he crafted welded metal constructions that incorporated industrial objects, foreshadowing later developments in sculpture.

During the 1940s and 1950s, his work shifted to more personal, landscape-inspired sculptures. These works possessed a delicate linear quality, akin to drawing in metal, and echoed the aesthetics of contemporary painting. Notably, Smith cultivated strong friendships with renowned abstract expressionist painters, including Jackson Pollock and Robert Motherwell, illustrating the interplay between different art forms during this period.

By the late 1950s, his sculptures started to assume monumental proportions. Using overlapping geometric plates of highly polished steel, his works developed a reductive and geometric aesthetic. These massive pieces of the 1960s are considered precursors to the minimal "primary structures" that emerged later in the decade, further exemplifying Smith's forward-thinking approach to sculpture.

Wikidata identifier

Q726169

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed January 30, 2026.

Country of birth

United States

Roles

Artist, painter, photographer, sculptor

ULAN identifier

500015402

Names

David Smith, David RoLand Smith, David Rowland Smith, Deṿid Smit, David Roland Smith, W Smith

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License. Accessed February 13, 2026.