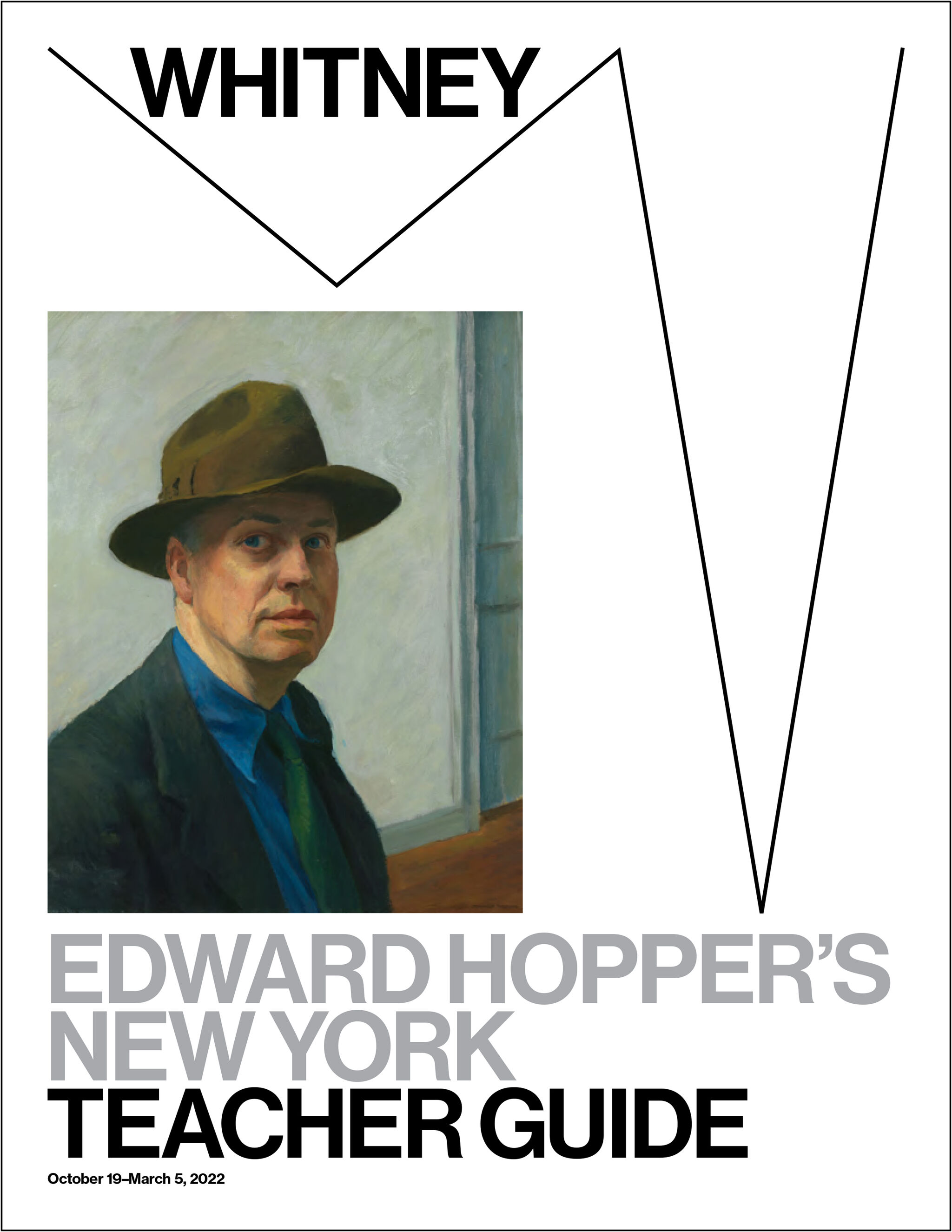

Edward Hopper

1882–1967

Edward Hopper was a keen observer of the everyday, which he transformed through his imagination into works of art that bear his signature tense, enigmatic atmospheres. A reflective and individualistic man, he was deeply attuned to the relationship of the self to the world, and his works increasingly focused on the psychological realities of his subjects. Hopper was frequently inspired by the two locations in which he spent most of his time: downtown New York, where he lived and worked in the same apartment on Washington Square from 1913 until his death in 1967; and Cape Cod, where, beginning in 1934, he maintained a second home and studio.

Hopper and the Northeast

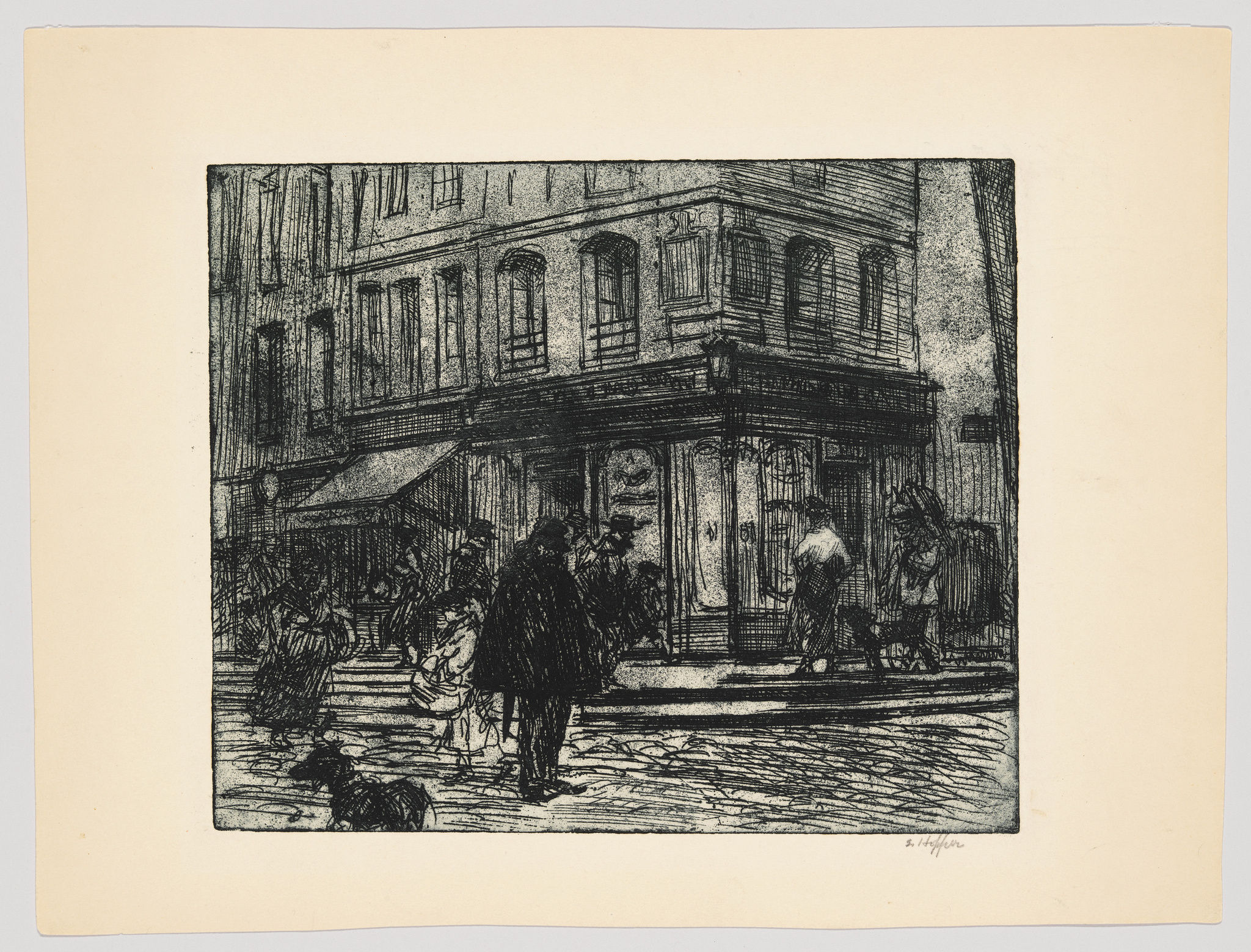

As a young artist in 1899, Hopper began commuting into the city from his hometown of Nyack—less than thirty miles north of Manhattan—to study at the New York School of Illustrating and then, one year later, at the New York School of Art. Afterward, he began pursuing freelance illustration work while continuing to paint. Funded by his commercial assignments, Hopper traveled to Paris for three extended visits between 1906 and 1910. During these trips, Hopper sketched and painted outdoors, creating luminous, loosely rendered cityscapes that helped him develop a sense of how to frame the built environment around him.

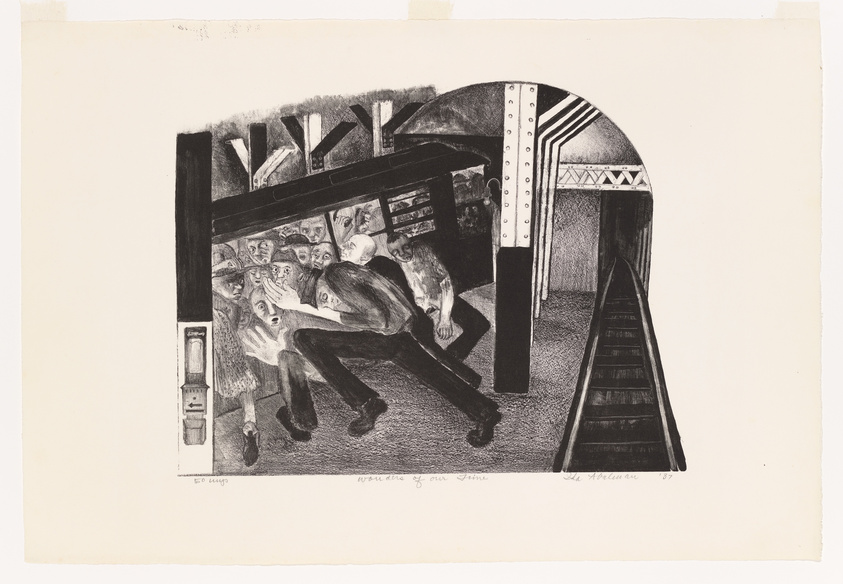

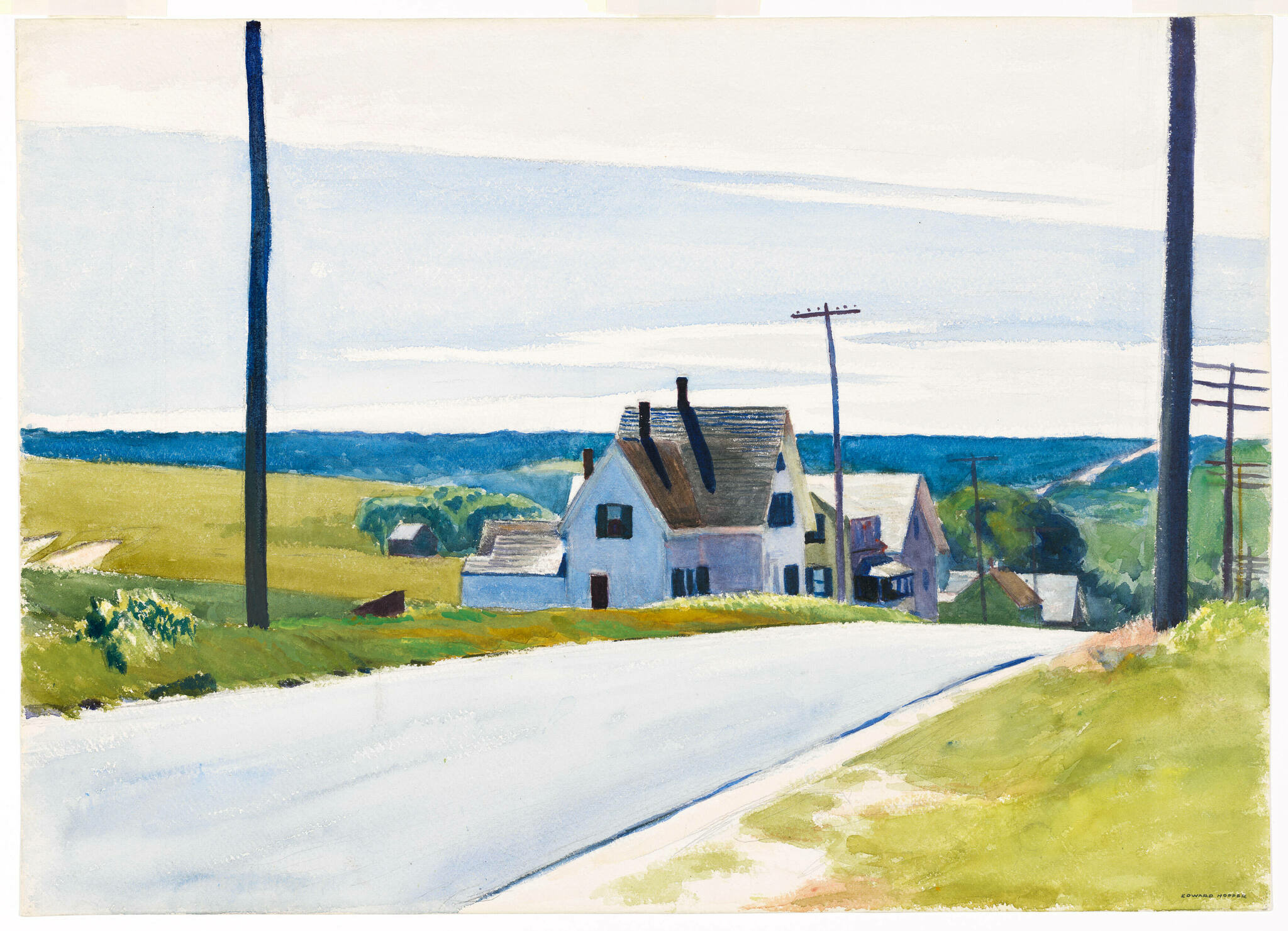

Back in New York, Hopper established his career as a chronicler of the modern urban experience. From 1915 to the early 1920s, he forged a rigorous printmaking practice, consolidating many of his impressions of the city and sharpening his compositional skills to experiment with light and shadow in black and white. The window became one of Hopper’s most enduring symbols. In his prints and mature paintings, he exploited its potential to merge the urban facades that had long fascinated him with views into the private lives lived within. Throughout his career, Hopper explored the city with a sketchbook in hand, recording his observations through drawing. He described his on-site sketching process as working “from the fact,” an effort to collect details directly from the world around him. While some of his compositions were based on specific sites, most of his paintings were based on a synthesis of elements from disparate locations, creating an imagined whole.

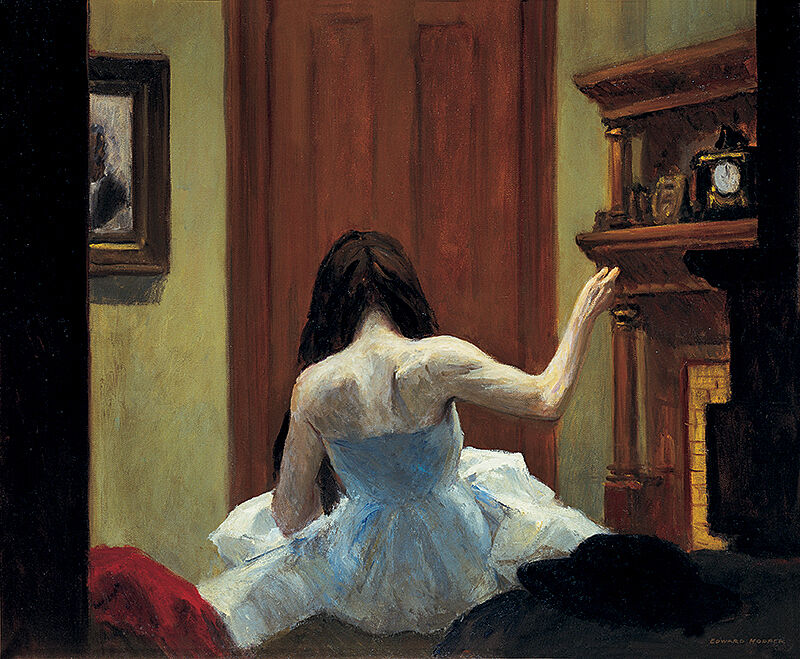

During this period, Hopper spent his summers visiting coastal towns in Maine and Massachusetts. The works he made there reflect his close observation of the natural environment. After his marriage in 1924 to the artist Josephine (Jo) Verstille Nivison, he continued to decamp in the warmer months. Together, the Hoppers traveled to Cape Cod and took road trips throughout the United States and Mexico. A number of Hopper’s preparatory studies for paintings depict Jo, who played an active role as his sole model, for which she often dressed in character and helped source props. The Hoppers’ collaborative scene staging was integral to Edward’s painting process.

Cafeterias, theaters, offices, and apartment bedrooms

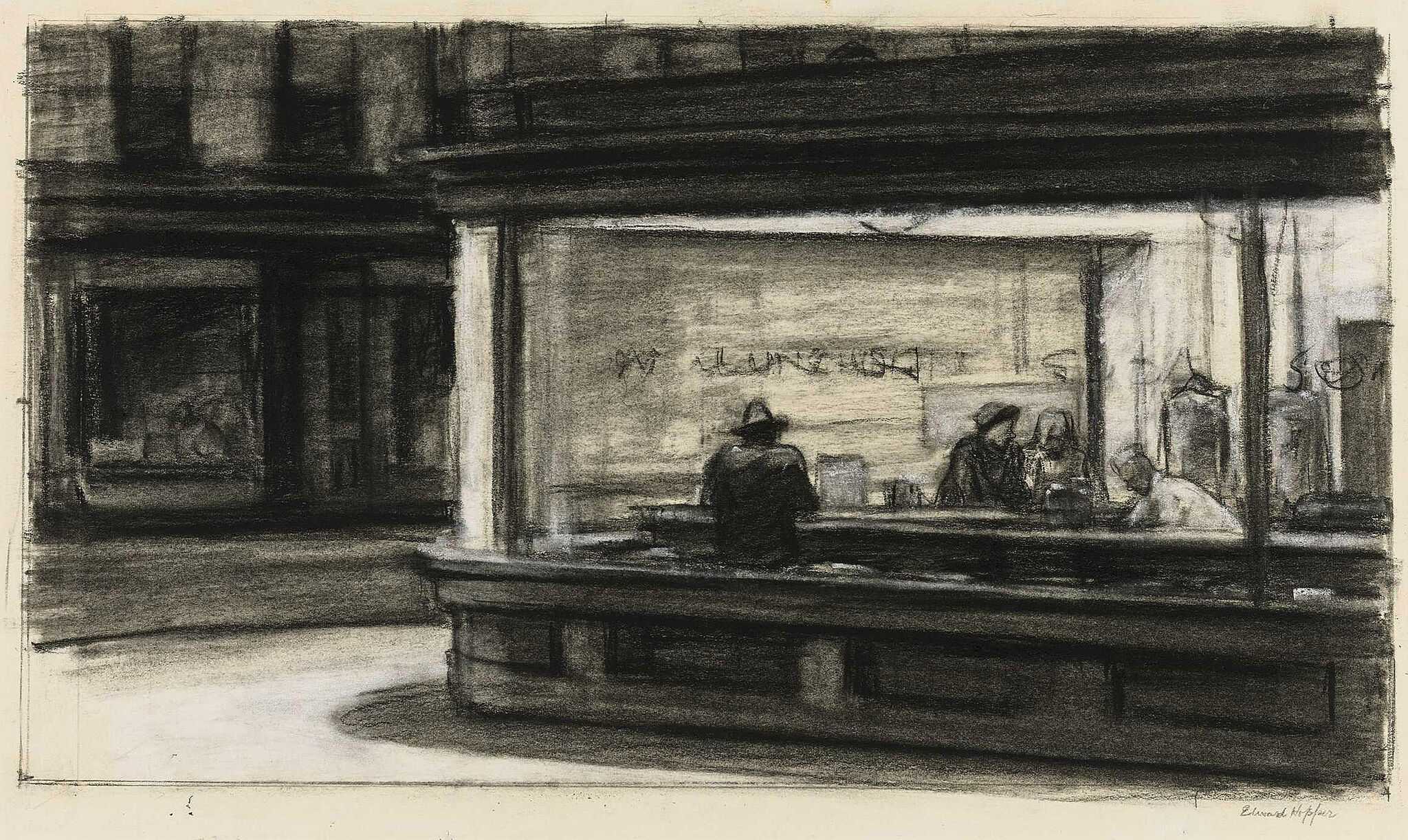

From the mid-1940s to the 1960s, Hopper produced a group of ambitious paintings characterized by radically simplified geometry and uncanny, dreamlike settings. These works were inspired by precise locations but depart from specific references to morph into ambiguous spaces of mystery, anticipation, and anxiety. At a moment when many artists in New York had turned to abstraction, Hopper pushed his compositions further than ever before in his charged images of cafeterias, theaters, offices, and apartment bedrooms.

Hopper and the Whitney

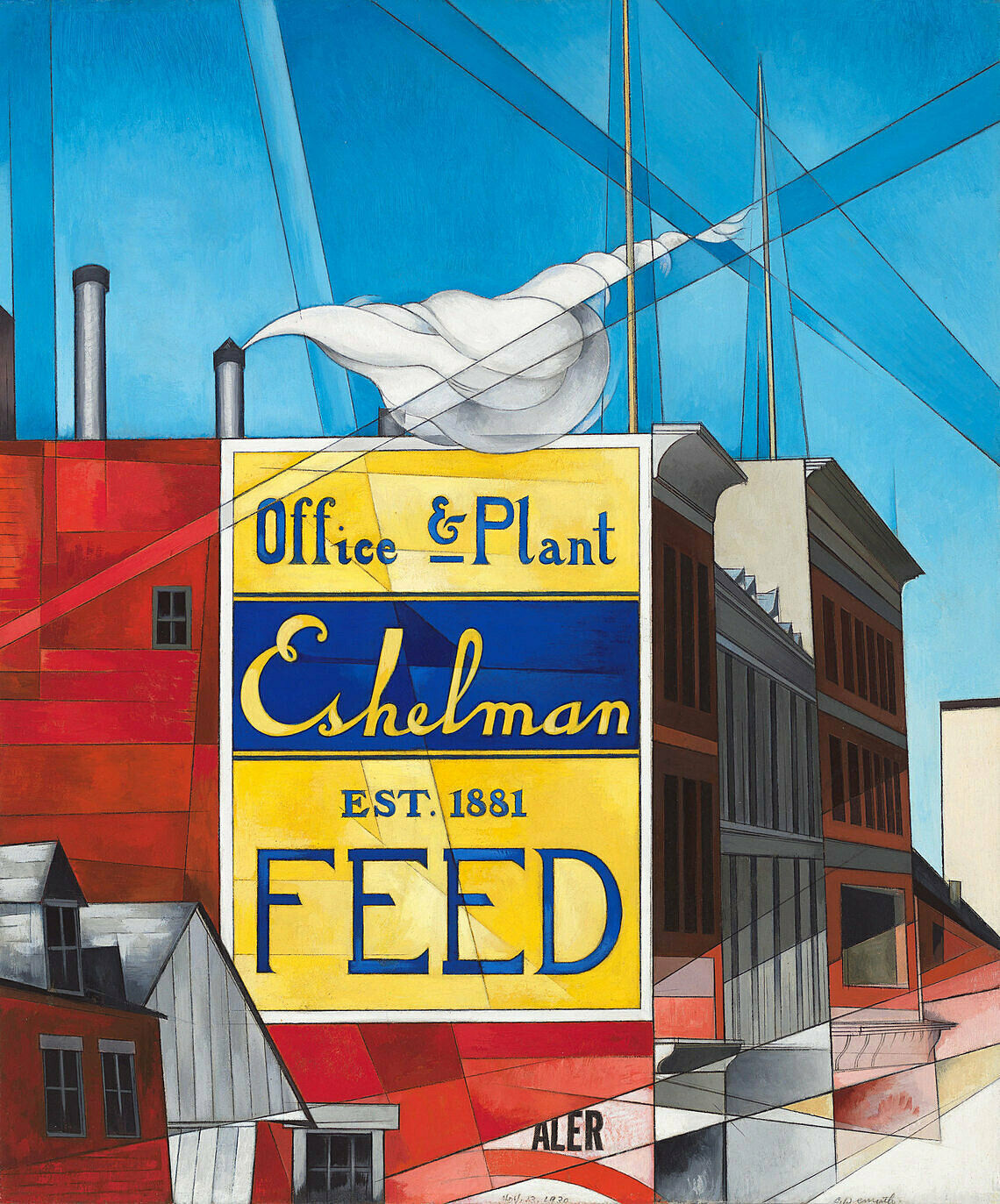

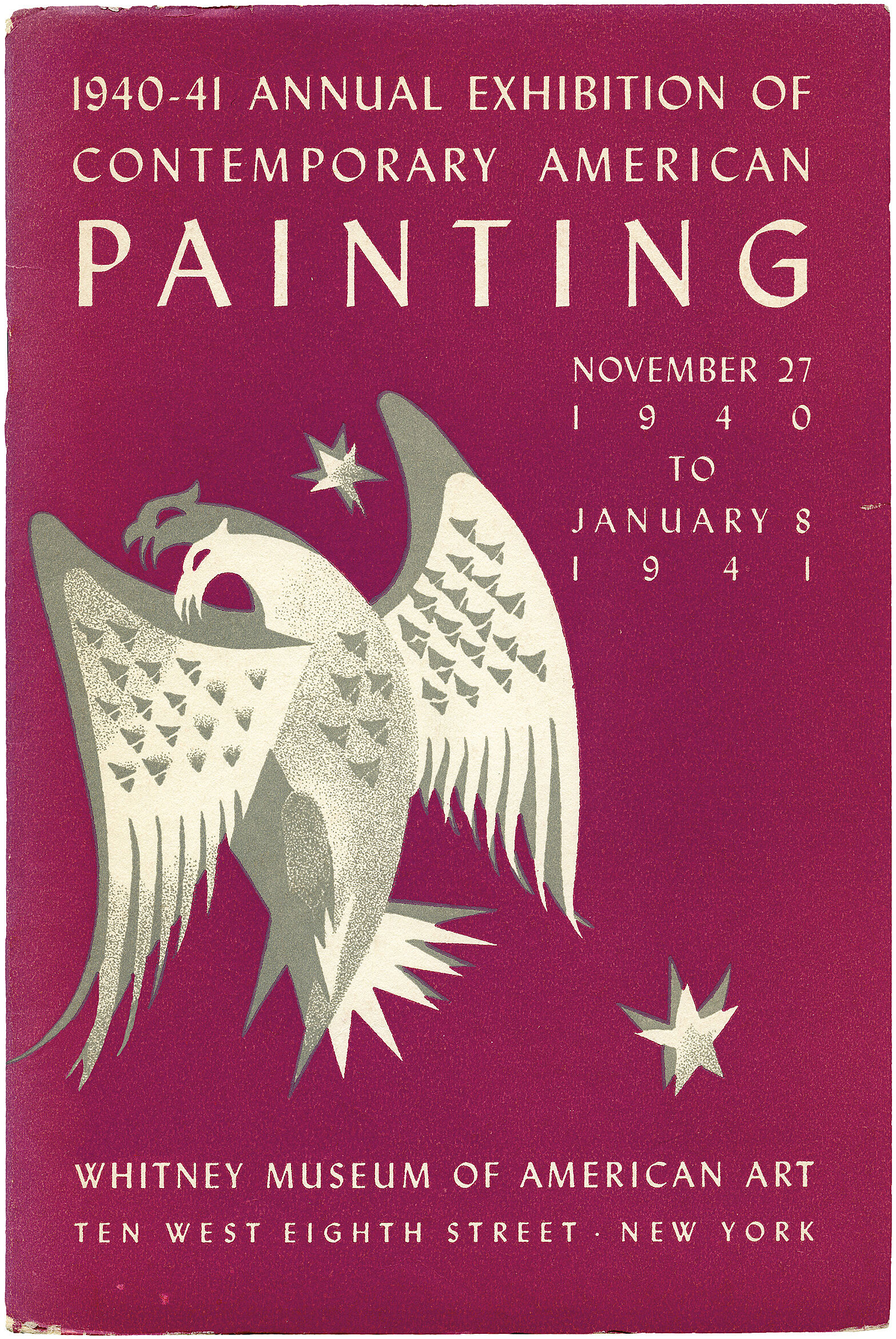

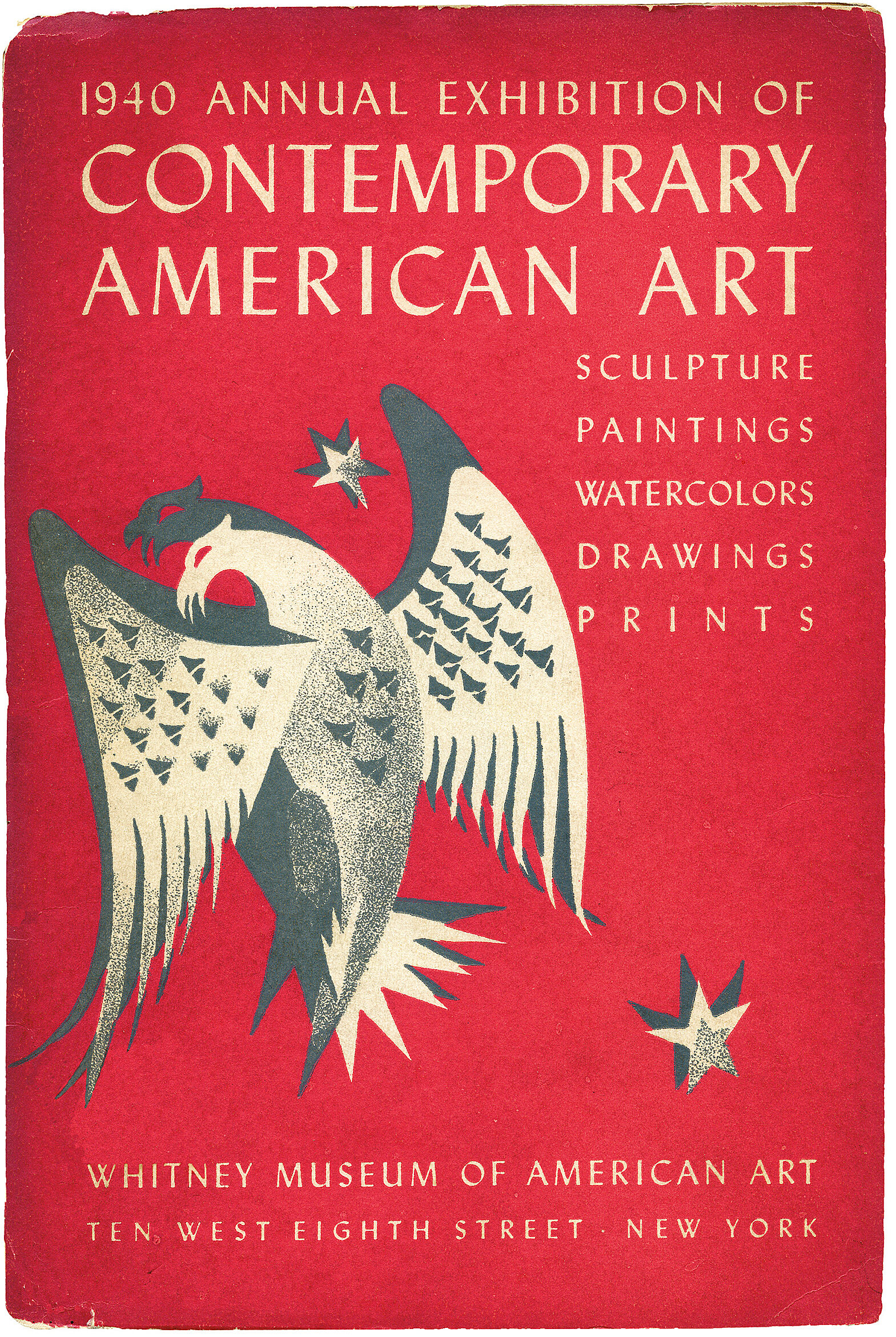

Hopper’s earliest exhibitions were held at the Whitney Studio Club, and his ties to the Whitney Museum of American Art deepened over the course of his career. His masterpiece Early Sunday Morning (1930), acquired just a few months after it was finished, would become part of the Museum’s founding collection. The Seventh Avenue building on which the painting was based was a short walk from Hopper’s studio on Washington Square. Painted more than a decade later, Hopper’s most acclaimed composition, Nighthawks (1942), also references his neighborhood, not far from the Whitney’s present-day site in downtown Manhattan. Hopper was included in the first Whitney Biennial in 1932 and participated in twenty-nine subsequent Biennials and Annuals through 1965, as well as several other group exhibitions. In 1950, the Whitney organized the artist’s second career retrospective exhibition; since the artist’s death in 1967, the Museum has organized many monographic exhibitions, large and small, and his works have been included in dozens of group exhibitions—more than any other artist.

Resources

Access additional Edward and Josephine Hopper resources.

Introduction

Edward Hopper (July 22, 1882 – May 15, 1967) was an American realism painter and printmaker. He is one of America's most renowned artists and known for his skill in depicting modern American life and landscapes.

Born in Nyack, New York, to a middle-class family, Hopper's early interest in art was supported by his parents. He studied at the New York School of Art under William Merritt Chase and Robert Henri, where he developed a signature style characterized by its emphasis on solitude, light, and shadow.

Hopper's work, spanning oil paintings, watercolors, and etchings, predominantly explores themes of loneliness and isolation within American urban and rural settings. His most famous painting, Nighthawks (1942), exemplifies his focus on quiet, introspective scenes from everyday life. Though his career advanced slowly, Hopper achieved recognition by the 1920s, with his works featured in major American museums. Hopper's technique, marked by a composition of form and use of light to evoke mood, has been influential in the art world and popular culture. His paintings, often set in the architectural landscapes of New York or the serene environments of New England, convey a sense of narrative depth and emotional resonance, making him a pivotal figure in American Realism. Hopper created subdued drama out of commonplace subjects layered with a poetic meaning, inviting narrative interpretations. He was praised for "complete verity" in the America he portrayed.

In 1924, Hopper married fellow artist Josephine Nivison, who played a significant role in managing his career and modeling for many of his works. The couple lived modestly in New York City and spent summers in Cape Cod, which influenced much of Hopper's later art. Despite critical acclaim, Hopper remained private and introspective, dedicated to exploring the subtleties of human experience and the American landscape. His depiction of American life, with its emphasis on isolation and contemplation, remains a defining aspect of his appeal and significance in the history of American art.

Wikidata identifier

Q203401

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed June 26, 2025.

Introduction

Hopper was one of the premier Realist painters of the 1930s and 1940s. In 1900, Hopper studied portrait and still-life painting with William Merritt Chase, but he preferred to take classes with Kenneth Hayes Miller and Robert Henri. In 1906, Hopper worked as a part-time illustrator, but by autumn of that year he went to Paris to study the work of European artists. His painting from this period and soon after reflects the influence of "plein air" painting and Impressionism. Hopper continued to work as an illustrator, garnering more critical and commercial success with it than painting, although he loathed this work. By 1925, Hopper began to develop his signature, where the focus is on only one or two solitary figures often consumed by vast outdoors spaces or cramped city streets. His landscapes also evoke a similar haunting loneliness. One of Hopper's most well known works is a poignant portrayal of urban alienation, "The Night Hawks" (1942). With the emergence of Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s, Hopper's work was seen as illustrative and obsolete. Pop Art and PhotoComment on works: realism resurrected his reputation. American artist. Comment on works: realism

Country of birth

United States

Roles

Artist, engraver, etcher, illustrator, painter, publicist

ULAN identifier

500031212

Names

Edward Hopper, Hopper [rejected]

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License. Accessed June 26, 2025.