Minisodes

Minisodes feature brief conversations about artworks and events in and around the Whitney. In these 5–10 minute episodes we explore top-of-mind art and ideas and what is happening now at the Museum.

The series is ongoing.

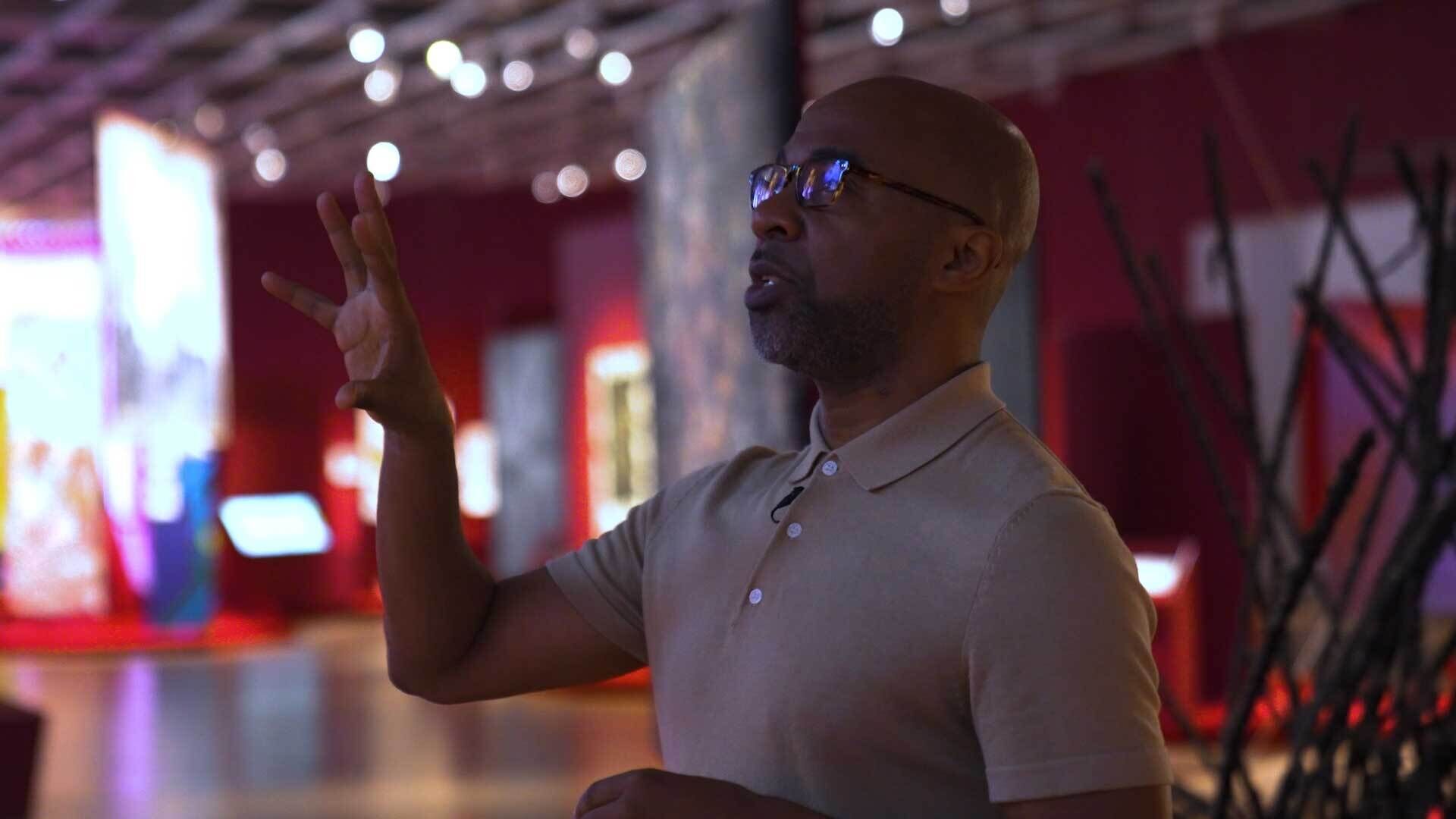

Matthew Rushing on Alvin Ailey

Minisode 21

In celebration of the exhibition Edges of Ailey, Matthew Rushing, the interim Artistic Director of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, takes us back to his first time seeing the company perform at the Wiltern Theater at twelve-years-old. Matthew discusses the memories of his mother taking him to see the performance, the experience of sitting in the front row, and the profound impact this moment had on the course of his life.

Released January 31, 2025

0:00

Minisode: Matthew Rushing on Alvin Ailey

0:00

[WADE IN THE WATER]

Narrator: Welcome to Artists Among Us Minisodes from the Whitney Museum of American Art, Alvin Ailey edition. We will be exploring the exhibition Edges of Ailey, or as curator Adrienne Edwards calls it, “extravaganza,” dedicated to the life, dances, and enduring legacy of the artist and choreographer Alvin Ailey. The exhibition is on view at the Whitney through February 9.

In this episode, Matthew Rushing, the Interim Artistic Director of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, takes us back to his first time seeing the company perform as a 12 year old in Los Angeles, an encounter that showed him the power of art and altered the very course of his life.

[WADE IN THE WATER]

Matthew Rushing: I first learned about Mr. Ailey and the company actually through my dance teacher. I was introduced to the arts through an afterschool program. I'm originally from Inglewood, California, a pretty rough neighborhood. My mother put me into an after school program to keep me focused and off the streets. This after school program integrated theater, a little bit of dance. We did a musical. I fell in love with it, but I had not made a decision to become a dancer until my dance teacher told me about the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. My mother took me to the first performance. Of course, it was sold out. It was at the Wiltern Theater, but there was a scalper outside of the theater, and he had two tickets. One was in the front row, and the other one was in the balcony. So my mother gave me the ticket that's in the front row. And I remember the curtain went up, and I remember hearing the dancers breathe as well, and I saw their sweat, and I remember seeing the ballet Cry. I had no idea what the ballet was about. I didn't know that it was Mr. Ailey's tribute to his mother and Black women, but what I experienced was the power of art and storytelling. I saw a woman who immediately started to look like my mother, my aunts, my grandmother. I started seeing images of my childhood and how my mother or other Black women appeared in my childhood, but it was all manifest on the stage. It blew my mind because I felt like somebody knew my history, knew my experiences, and was telling my own story. I was like, how is it possible that my life experience is being danced before me? It felt like it was just for me, that they were dancing. So I think that's what really solidified my whole connection to dance, because my first experience was being affirmed that my own experiences are important enough to be danced about.

To experience that as a young person, it's life-altering. When you see excellence at a certain level, and you see people who look like you in the midst of the excellence, it immediately says “you can do it too.” And at that moment, that's what I felt. I was like, not only do I want to do this, but I want to do it here in this company. I needed technique. I needed training. I had no training up until that point. And I auditioned for the High School for the Arts, got into the High School for the Arts, trained for three years straight. My senior year, I auditioned for this company. Not thinking I would get a place in the company, but at that point, you could get a full scholarship to the school. It just so happened that the director of the school, the late Denise Jefferson, as well as Sylvia Waters, who was the director of Ailey II at that moment, and Judith Jamison, director of First Company, were all at my audition. So I got a full scholarship, and I also got a promised position with Ailey II, and so that's basically how the journey started. Trained at the school for a summer, was in Ailey II for one year, and then became part of the First Company. Eventually choreographed four ballets for the company, promoted to Rehearsal Director in 2010, Associate Artistic Director in 2020, and now I'm Interim Artistic Director.

[WADE IN THE WATER]

If you'd have asked a young Matthew at 12 or 13 if he would be interested in going to see a modern dance concert, my answer would be no. I guess I would assume there was nothing there for me, there was nothing that I could relate to, but that experience that I had at the Wiltern Theater changed all of that.

It actually made it so clear that this whole modern dance thing is not only accessible, it's part of who I want to be. That was a clear epiphany. I was watching who I am and also what I would want to be on stage. I have no doubt that the seat that I'm sitting in right now is exactly where I should be, and it's one of the reasons that I was put onto this Earth, and it was one of the reasons I was given the gift of dance, but I always go back to Mr. Ailey as the entry point. I would have never experienced it if he hadn't done all that he's done. He talked about his roots. He talked about his blood memories. He also talked about the importance of his family being able to come to the theater and understand what they're watching. So it's not a thing of it being an elitist art form. Yes, we're going to aim high, but we're going to speak in a way that everybody can either understand or at least draw their own interpretation from. And I love that accessibility paralleled with integrity, paralleled with excellence. I think he just understood dance and humanity. And when you put those two together, there are no boundaries.

[WADE IN THE WATER]

Narrator: Artists Among Us: Edges of Ailey Minisodes are produced by SandenWolff with the Whitney Museum of American Art. Anne Byrd, Nora Gomez-Strauss, Kyla Mathis-Angress, Emma Quaytman, and Emily Stoller-Patterson.

Minisode: Matthew Rushing on Alvin Ailey

Mickalene Thomas on Alvin Ailey

Minisode 20

In celebration of the exhibition Edges of Ailey, artist Mickalene Thomas recalls her first encounter with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, and the influence it has had on her life and work. Thomas created the work Revelation, a portrait of Katherine Dunham, specifically for the exhibition. In this minisode, Thomas shares an experience of seeing Revelations performed by the AILEY company for the first time in New York in 1995. Thomas also describes moments of overlap between the language of dance and her art practice, and what any artist can take away from Alvin Ailey’s work.

Released January 31, 2025

0:00

Minisode: Mickalene Thomas on Alvin Ailey

0:00

[WADE IN THE WATER]

Narrator: Welcome to Artists Among Us Minisodes from the Whitney Museum of American Art, Alvin Ailey edition. We will be exploring the new Edges of Ailey exhibition, or as curator Adrienne Edwards calls it, “extravaganza,” dedicated to the life, dances, and enduring legacy of the artist and choreographer Alvin Ailey.

The exhibition will be on view at the Whitney through February 9th. In this minisode, the artist Mickalene Thomas recalls her first encounter with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and the influence it's had on her life and work. Thomas, whose paintings, photographs, and collages often depict strong, bejeweled Black women in colorful, dynamic settings, has a new commission on view in the exhibition. The large-scale work brings together imagery of Mr. Ailey's peer, the great modern dance innovator Katherine Dunham, with his iconic work for the Ailey Company, Revelations. Dunham is best known for introducing African, Caribbean, and South American styles and traditions into the lexicon of modern dance, while Ailey's Revelations is a meditation on the Black American spiritual experience rooted in the choreographer's Southern Baptist upbringing. Taken together, as Thomas does in her lilac hued and rhinestone studded work, they speak to the outsized role that dance and its innovators have played in shaping Thomas's own artistic life.

[WADE IN THE WATER]

Mickalene Thomas: When I moved to New York in ‘95 to go to Pratt Institute, I had a friend who was very involved with dance. She was a dancer herself. She, I think, took some dance classes with Ailey. And she was like, oh, you gotta come to this performance with me. And I just remember just being like, whoa, this is like, next level. And for me also, it was being in New York, an emerging artist at the time, and seeing a production on that level with so many incredible African American dancers. When I saw Revelations, it was kind of, for me, like this out-of-body experience because it felt so familiar and it felt so at home. It felt like I understood the journey of our people and what they've gone through. I felt like he was really holding a mirror up to, like, what we've endured and where we are and where we're going. That we can get through this, like there's this moment of recognition for ourselves. And so for me, it's a real deep spiritual thing. I think of my grandmothers. I think of, like, all of the women in my life. I think of my mother, I think of my aunties, and I love that. And I think for the work that I presented here with Katherine Dunham as the subject, I really wanted to personify that essence that isn't always easy to articulate because it's an experience. And I think Revelations is like an experience. I think that's why it stays with me. And it stayed with me with the connection with Katherine Dunham and Ailey, because I feel like he learned a lot from her when it came to the spirit. Like, bringing the spirit. And to the physical movement of dance. And that's what I think Revelations does. It brings it home. It grounds you. It's the foundation.

I've always loved dance, but I think that's when I really fell in love with it. Because one thing about dance that I respond to is that it's movement and space. Sculptural, you know. It's physical. It's like this sort of spiritual relationship with your body, to move it in ways and space and have the viewer see you doing that in real time. And some of the movements you know are challenging. And when I see dancers, I have a real response to it physically. And I also think, oh, I want to do that. I want to, I want to dance like that. I want to move like that. I want my limbs to feel like they can do all of these things that I know that they can't because I don't have the training. And I still, I go to dance. I take dance classes like Mark Morris. And, you know, I've taken some classes at Alvin Ailey just because I like to be able to understand my body in the same way, you know, which is, it's a language, right? It's a language with your body. Like, your brain is telling your body to do something in space and you're able to do it. And it's like, wow.

[WADE IN THE WATER]

What have I taken away from dance and brought to my art practice? It's different because it doesn't look like dance, but it does have a lot of layers and movement and things that are in it, the collaging. So I think there's something analogous to it. There's a relationship to dance. Oftentimes, I think some of my gestural marks and linear marks are about a particular movement that I want the viewer to feel. It's not like a whole dance in my space of my studio. But it's a part of my life. It's an important part of my life. I will go to a dance performance before going to the movies.

[WADE IN THE WATER]

Alvin Ailey was an innovator, a shapeshifter. I think he is just a genius at his art form, and I think the Whitney Museum of American Art is an important place to consider Ailey because he's an American artist, right? And he's created American dance for all of us. I think anyone, any person who's interested in creativity can take away a sense of being authentic, and just, relationships with others. That's your foundation, is your relationships with others.

[WADE IN THE WATER]

Narrator: Artists Among Us: Edges of Ailey Minisodes are produced by SandenWolff with the Whitney Museum of American Art. Anne Byrd, Nora Gomez-Strauss, Kyla Mathis-Angress, Emma Quaytman, and Emily Stoller-Patterson.

Minisode: Mickalene Thomas on Alvin Ailey

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the Last Gullah Islands

Minisode 19

In this episode, photographer Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe talks about documenting the Gullah Geechee people of Daufuskie Island. Over a five-year period, the photographs reveal a change over Daufuskie as developers and Hurricane David make their way to these last Gullah Islands.

Released December 23, 2024

0:00

Minisode: Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the Last Gullah Islands

0:00

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe: I am Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, and I have been photographing since a little over fifty years now. I became interested in the Gullah culture when in college I did a six-month independent study from school on the west coast of Africa. And on my first morning walking out of the student hostel, coming out and looking to my right and looking to my left on the street, I just noticed all I saw were Black people. And that experience was one of, "Wow." It created for me an experience that immediately took me back to growing up in my own African-American culture and in my community that I connected immediately.

I'd always had an interest in showing the Black community, my community, in its joyful and celebratory and ritual communities that we are and how we celebrate our culture. And when I finally had an opportunity to go to the South Carolina and Georgia Sea Islands, that was in 1977, March of 1977, and I didn't know a lot about the Gullah Geechee culture except that I knew they were direct descendants of slaves.

And coming off of the training of being a street photographer at the school I attended and the teachers that I had at that time, who were remarkable teachers, Gary Winogrand, Joel Meyerowitz, Jay Maisel, Arnold Newman. That experience then made photographing on the South Carolina Sea Islands and the Georgia Sea Islands even more accessible to me because I had that experience of just walking on the street and photographing people.

On islands like Edisto and Wadmalaw Island and Johns Island, you could visit these places by getting to the particular islands on a bridge.

But a friend of mine said, "Sounds like you had a great first trip to the Sea Islands. But you haven't been anywhere until you've gone to Daufuskie Island." Daufuskie. It sounded interesting. I did not know at the time that there was no bridge linking Daufuskie Island to the mainland, like all of the other islands I had visited. And when I discovered that, I knew this was going to be someplace special. So I did call her friend who has now become a lifelong friend of mine, and that's Dr. Emory Campbell. And Emory introduced me to a few people. And the one person he introduced me to was the lady that I eventually stayed with on all of my trips to Daufuskie. And the moment that I stepped on Daufuskie Island, I could hear on my very first trip, a language that was spoken that was quietly spoken in a way that maybe I wasn't really meant to hear this language, but it was spoken among the people on the island. But I still received a very warm reception.

And I knew that a lot of people didn't like my constantly taking pictures of them and they would often ask me, "Why are you taking a picture of that? You've already taken a picture of that. Why are you doing it again?"

And then in 1979, Hurricane David came along and it blew down a couple of the structures that I had been photographing. One was an old praise house, a slave praise house, and it was completely blown apart. It was gone. And that's when people were coming to me and saying, "Ah, so that's why you're taking pictures." They began to understand what was happening to their island and what was happening over time. They allowed me the freedom and the generosity and the openness to allow me to come into their lives and photograph them.

So the story for I think many of the Daufuskians and development was as developers started to come onto the island, they were offering what people felt were large sums of money for their land because while the Daufuskians didn't have a lot of money, Daufuskians did have a lot of land. They were a land- rich people, and this is what developers were looking for.

Over a five-year period, I visited Daufuskie on and off the island many, many times, and I stayed with this woman that Emory had introduced me to, and her name was Susie Smith. And without Susie, I don't think I would ever have gotten under the good graces of Blossum, known as Lavinia Blossum Robinson. She was the matriarch of the island. So I was passing by Blossum's house walking on the island one day and walked up to her front porch and she was sitting on her porch, and I knocked on the door, and she invited me to come in, which I did. And I asked her how she was doing, and she was in a pretty good mood that day. So I came in and asked her if I could make a portrait of her. And she kind of shook her head and said, "You've made enough portraits of me." And I said, "But this is special. You're sitting on your front porch and I'd like to just get a portrait of you on your porch. Come on, Blossum."

So I had to coax her into this picture of Blossum's face with this warm smile. And I think the warm smile is saying, "I know you've had a picture of me before. You're taking another one?" But she smiled. She was surrounded on the screen porch by such beautiful light. The shadows, you can see just about all the details in the shadows. You can see the braids in her hair, and you can see the gray of her life and the markings on her face that tell you something about this woman who knew so much and who was so strongly rooted on this island born and died on Daufuskie, and this was her island, the island matriarch.

Blossum knew that change was going to be coming to Daufuskie. They had already started talking about putting in a spa on Daufuskie in a well-known hotel chain, and she was not going to have it. So Blossum was, along with many of the Daufuskians, she pretty much led that charge was very much against development at the time. When Blossum died, I got a phone call from the island to let me know that Blossum had died and I better get down because there's going to be a funeral and I should come. And I did. In a couple of days, I was down on Daufuskie and photographed Blossum's funeral, and people talked about how she would be standing at the dock with her fist in the air keeping the developers away. And having known Blossum, that's exactly what she would've done.

Minisode: Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the Last Gullah Islands

Exhibition Curator Adrienne Edwards on Edges of Ailey

Minisode 18

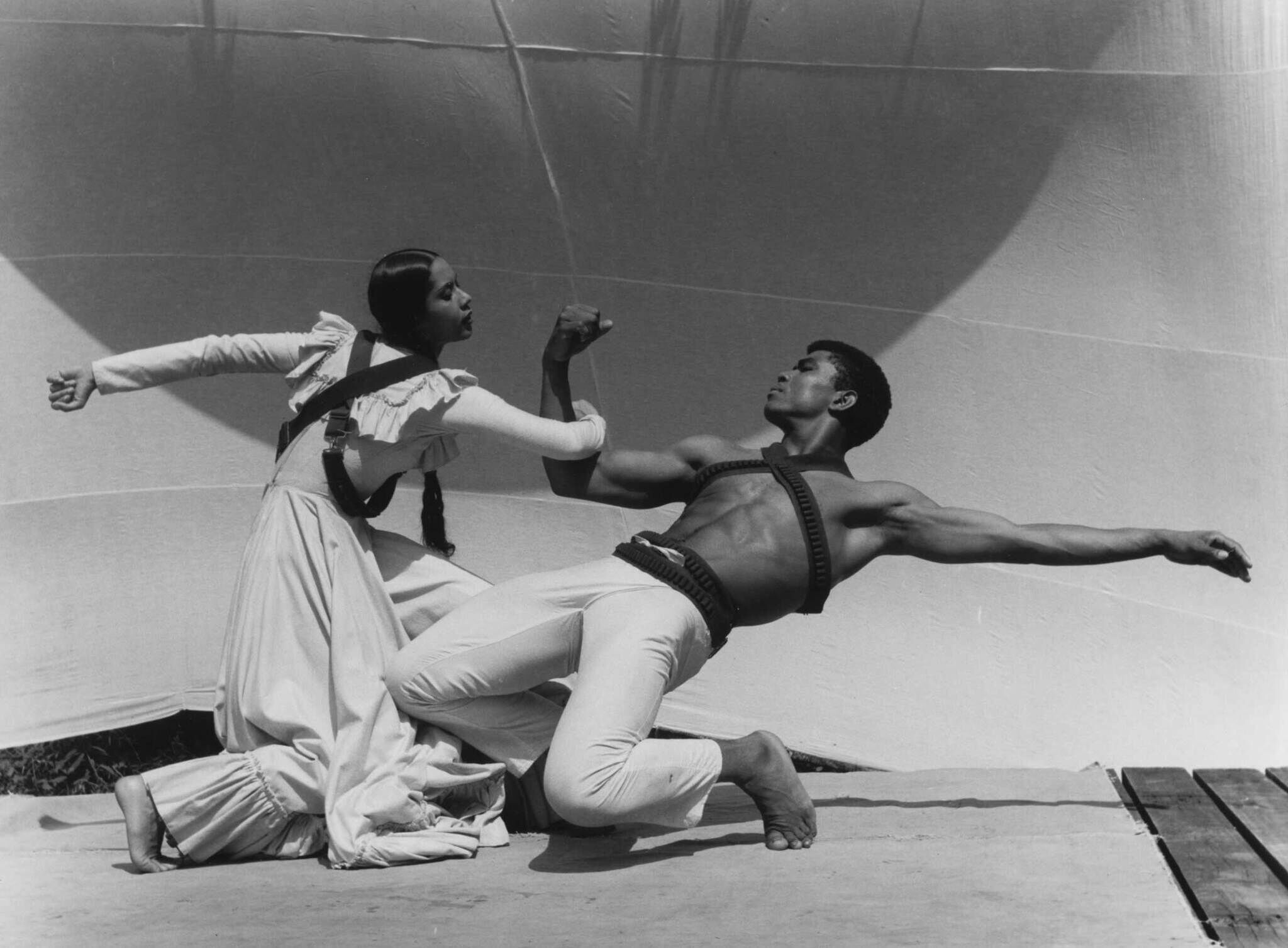

Through an immersive eighteen-screen video installation, illuminating archival materials, an ambitious performance program, and wide-ranging artworks by eighty-two visual artists, Edges of Ailey explores a titan of modern dance whose impact reverberates across media and time, and whose beloved company, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, remains a global cultural force to this day. In this minisode, the curator of the exhibition takes us through her vision for the show and some of the discoveries she made along the way.

Released September 18, 2024

0:00

Minisode: exhibition curator Adrienne Edwards on Edges of Ailey

0:00

Narrator:

Welcome to Artists Among Us Minisodes from the Whitney Museum of American Art, Alvin Ailey edition. We will be exploring the new Edges of Ailey exhibition or, as curator Adrienne Edwards calls it, “extravaganza,” dedicated to the life, dances, and enduring legacy of the artist and choreographer Alvin Ailey. The exhibition will be on view at the Whitney from September 25–February 9.

Through an immersive eighteen-screen video installation, illuminating archival materials, an ambitious performance program, and wide-ranging artworks by eighty-two visual artists, the exhibition explores a titan of modern dance whose impact reverberates across media and time, and whose beloved company, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, remains a global cultural force to this day.

In this minisode, Edwards takes us through her impetus and vision for the show and some of the discoveries she made along the way.

Adrienne Edwards:

Well, the show really came out of a kind of long-standing sort of trajectory in recent years. There have been so many museums that have done exhibitions about dance. And it occurred to me on multiple occasions, why not Alvin Ailey? There couldn't be a, I think, more international brand in terms of contemporary dance. And so I was really sort of asking that question of our field and also of our institutions.

Alvin Ailey was born in Rogers, Texas in 1931, and dies from AIDS-related complications in 1989. He is among the most important cultural figures, not only in the United States, but abroad. And he had a vision for dance that was incredibly modern, incredibly rigorous, incredibly imaginative, and it was about freedom, it was about love, and it was about excellence.

Ailey comes to New York in 1954, and like so many dancers did at the time, really made his living doing Broadway shows, and then uses these resources to gather a group of dancers to present his very first work that would become known as part of the Ailey Company in 1958 called Blues Suite. It's interesting because I've been going to see Ailey for so long, I feel like I'm actually hardwired with Ailey in a way that I can't actually remember the very first performance that I saw. So it was something I was very familiar with, and I actually thought maybe I was even too close to Ailey to get enough of a sort of perspective on how to think rigorously and critically about the work and who he was. But that all changed once I got into the archive.

Ailey was a copious keeper of journals and diaries, and they include everything from to-do lists to character studies for roles in his dances. What we found that was really surprising is his own short story writing, his own poetry. He also wrote things like “No Leg Warmers,” wonderful notes to his lovers reflecting on their positive and negative qualities. And then you would find just almost things that seemed very positive, like he was reassuring himself. One said, “We teach people to feel, to own their own feelings.” So we could see him unfold as a creative person. And it was just an incredible discovery for me as a curator and a scholar to have access to that.

The other thing is that we found almost 200 videos made during his lifetime alone. And then the question became, how do we present this to audiences? And there are many different approaches, but Mr. Ailey was always about spectacle, loved theatricality, knew that we didn't have the right to bore people just because we might have talent or knowledge. So in putting the show together, we've kept really close to Mr. Ailey and the things that he believed in. And he said, you know, I wanted to be a painter. I wanted to be a sculptor. I wanted to write the great American novel. I wanted to be a poet. And that, to summarize, dance somehow could hold all of those things for him.

I've been working with two wonderful filmmakers, Josh Begley and Kaya Liu to basically create a montage across eighteen screens in the gallery that will take you through a kind of arc and evolution of his life by focusing very specifically on key dances and the historical, political, and social context and cultural context that is occurring while he is making them.

And then there are eighty-two other artists in addition to Mr. Ailey who are in the show, some represented by multiple works. The earliest is from 1851 and the most recent are made especially on the occasion of the exhibition, so have been made this year. The ideas in Mr. Ailey's dances—which these artists share although they realize them in different ways—traverse the Black body in dance. Like, what is Blackness in dance? So many artists have made works representing this. But also a kind of Southern imaginary, the South for Ailey and those who preceded him was not only about the Southern United States, but was also very much about what is a Black diaspora. The Caribbean, South America, in particular Brazil for Ailey, but also the western coast of Africa.

So it's almost like a kind of circum-Atlantic history in a way. Southern imaginary also looks at Black spirituality, which is, of course, about a kind of Southern Baptist church or a kind of evangelism within the Black tradition. But it is also equally about Haitian voodoo. It is about Brazilian Candomblé. It is about the way those practices originate in different cultures on the west coast of Africa. So this idea of spirituality as the sustaining force, as a way of speaking to struggles and challenges and also desires is an incredibly important subject. Then there is this question of movement. And when I say movement, I mean like the movement of a people. So we think about ideas about Black migration, which include the Middle Passage from the West Coast of Africa to the Americas, but also even within the United States, thinking about the Great Migration, not only what were the sets of conditions that led to it, but also the unknown of what life elsewhere would be.

I mean Mr. Ailey himself, who was born in Rogers, Texas in 1931, goes with his mother in the early forties to Los Angeles, leaves Los Angeles, goes to San Francisco for a while, leaves San Francisco and ultimately comes to New York. And so he himself exemplifies this sort of migratory pattern that really became about directing us towards possibilities.

And I feel that that's something that Ailey thought a lot about. And then, of course, the openness of what is possible leads us to then demand our own liberation. And so for Ailey, this idea of freedom and how the body becomes the vehicle through dance in which to express that freedom, practice that freedom, embody that freedom, it's really very important to so many other artists. And that freedom is, you know, about a kind of Black liberation. But that Black liberation is also about a Black queer liberation. It is about the sort of acknowledgment of the complexity of who he was as a person. And so there are all of these ways in which there's a sort of sinew, obvious or not, between Ailey and these various artists in the show.

Everyone has an Ailey story, but I think I was surprised by the extent to which so many contemporary artists not only knew who he was, but really had thought about what he achieved and what he stood for. But artists are fundamentally curious people. And for that reason, much like Ailey himself, their interests are broad and deep and incredibly multilayered. And so I think that what became clear to me is that they really saw him as someone who exemplified excellence. I mean, a lot of the conversations were about, wow, can you imagine what it was like to achieve what he did in his lifetime? Like it's not today, we're talking about 1958 at a time where there was one place in New York City where the dance studios were integrated, where you could go to study at the New Dance Group. That's really quite something to contend with because we think about these aspects of American culture and life and politics as being really relegated to the American South when in fact it was throughout this country. And if you look at Ailey dancing, there's something so visceral and vital about the way that he held a stage. And I think that that kind of like insistence on telling his own story, but making it a kind of universal story, if you will, I think was quite an achievement on his part. And I think it's a big part of his legacy and part of the reason that it continues to be so exemplary.

Narrator:

Artists Among Us Edges of Ailey Minisodes are produced by SandenWolff with the Whitney Museum of American Art: Anne Byrd, Nora Gomez-Strauss, Kyla Mathis-Angress, Emma Quaytman, and Emily Stoller-Patterson.

Minisode: exhibition curator Adrienne Edwards on Edges of Ailey

A Whitney curator on how a painting by Eldzier Cortor found its way into the collection

Minisode 17

Associate Curator Jennie Goldstein discusses how Day Clean, a painting by Eldzier Cortor (1916–2015), recently found its way into the Whitney's collection. She describes Cortor's interest in depicting Black American life in the South and how he drew influences from his travels to the Caribbean, African Art, European Surrealism, and American Realism.

Released August 20, 2024

0:00

Minisode: A Whitney curator on how a painting by Eldzier Cortor found its way into the collection

0:00

Narrator:

Welcome to Artists Among Us Minisodes from the Whitney Museum of American Art. Today, we’re exploring an exciting new addition to the Whitney’s collection: Eldzier Cortor’s painting Day Clean. The richly textured painting depicts a pair of figures standing on a porch with day breaking on the horizon. Cortor was interested in depicting Black American life in the South and drew influences from his travels to the Caribbean as well as from African Art, European Surrealism, and American Realism. Here, Associate Curator Jennie Goldstein talks about this painting and its unique path into the Whitney’s collection:

Jennie Goldstein:

Sometimes works come to our attention almost by accident, by someone reaching out to us thinking that we might be a good home for something that has been in their home.

This addition to the Whitney's collection was quite fortuitous. In 2014, Cortor’s son worked with his father to place some works by the artist in museum collections, including the Whitney's collection. We were able to acquire some prints that the artist had made in the 1950s. And this was incredibly exciting to us but we did not at the time acquire a painting. And then one sort of came to our door; a donor who had this painting––something they had inherited from their grandfather and had it for decades––thought of us as a place where this painting could have another life beyond the one she'd lived with it and the one that her grandfather had lived with it. He came into possession of this painting through barter trading medical services for the painting with the artist, which is not an uncommon practice and one that still happens.

Part of what was so amazing to us was that the donor lived so close-by, the painting was in the neighborhood all this time. And this was an artist who we as curators here at the Whitney had been so interested in and now is going to be here and on view. Eldzier Cortor is this incredible figure––I mean, imagine being born in 1916 and dying in 2015––he changes, the radical technological innovations, the stylistic shifts and twists and turns. And he saw all that and was steadfast in his devotion to representation and to seeking out this sense of eternal that he was so taken with.

Eldzier Cortor was born in 1916 in Richmond, Virginia, and a year later his family moved to Chicago. They were part of the Great Migration––millions of Black Americans who moved from rural parts of the country to urban centers seeking better opportunities and fleeing segregation and other forms of racist oppression. He went to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the mid 1930s and, like many artists who came of age during the Great Depression, he was very engaged in Social Realism depicting the lives of ordinary citizens in the south and west sides of Chicago, where he grew up in predominantly Black neighborhoods and thinking about the struggles and financial limitations that so many families were subject to at this time.

And in the early 1940s, he grew increasingly interested in leaving Chicago and exploring more of the United States and the Caribbean islands. He was deeply interested in connecting to a kind of broader African diasporic history, thinking about the ways in which the descendants of enslaved Africans lived throughout North America and the Caribbean islands. At the time, he was able to receive funding from the Julius Rosenwald Fellowship in 1944 and in 1945, which allowed him to travel to the Sea Islands off the coast of South Carolina. He took two trips and went to St. Helena Island. He was really interested in the Gullah Geechee communities in these barrier islands off the coast of South Carolina, Georgia, and into Florida, where enslaved Africans worked on large plantations and were relatively isolated because of the island landscapes, and were able to, as a result of this isolation, retain more of their cultural heritages from the places they came from in Africa.

“Day Clean” is an expression from Gullah Geechee culture. It means a new day, that whatever happens the day before, we can kind of wipe our slate clean and start a new day clean. So you can see some of this playing out in the composition of this painting where you have these two figures. (04:00): They're both anonymized, they're not identifiable people that he met, and the day is just sort of breaking through the clouds here. When you get up close, you can see pinks and blues and whites peeking through the surface of this composition as the day breaks. So, it is both a kind of literal day clean, a new day is starting, and this more kind of metaphorical sense of the title, that whatever came before, we can start anew.

In this composition, you can see two figures standing on the porch of a house, probably raised up in this part of Lowcountry, South Carolina. It's very wet and marshy and there are some mysterious things happening in this building; pieces of wood that don't quite connect, a roof that seems to be peeling, but also maybe visceral and bodily, and all this strangeness is echoed in some of the ways that the artist paints. (05:08): When you get up close, you'll see that he adds oil paint in globs where the amount of paint on the surface has a texture to it. (6:13) There are other strange elements of this composition where the architectural roof of this house is flat up against the picture plane deeply pitched. (5:25) This adds to the sense of drama, the sense of mystery that we don't totally know what's happening here as this new day begins.

He had a deep fascination with depicting women in different kinds of contexts–– as this exemplar of Black excellence––and a deep fascination with Black American experience. But they're not specific portraits. They are in their own way kind of abstracted, but they pull from these lived experiences that he had.

One of the things I think is interesting is his use of color. You see in both the dripping Spanish moss, which is a plant very common in this Lowcountry of South Carolina, you see certain colors repeat: red from the roof, from the hat, the roof of the small church, the crown that this young man is wearing peaks out from the trees, even though that isn't a color that you would actually find in Spanish moss. Same with the pink that recurs in the sky with the sunrise peeking through the Spanish moss, and again in the shirt that this woman is wearing. So this purposeful use of color connects the landscape with the architecture and with these two figures so that they're all implicated in each other. The setting that they're in impacts their experience of the world and vice versa.

Cortor was making art in the 1940s at a time when many American painters were interested in an American version of Surrealism that was often called Magic Realism. The idea here was to pull from some of the tropes of Surrealism, which was a European art movement interested in the unconscious in our dream life, but adding to that this kind of particular interest in American society––whether that's societal ills, poverty, or, in Cortor’s case, a world that was so very different from his own but one that he still felt this kind of connection to. So, the ways in which the elements of this story and the anonymized figures do and don't add up pulls from these surrealist traditions and brings this very American content to it––this complicated, violent U.S. history.

What's interesting to me about it is how much of it is so clearly from this very specific location––this isolated place that had a mythical and magical pull on the artist. We can just imagine what it would've been like for an artist raised in a place like Chicago to get on a bus, take this trip to a barrier island off the coast of South Carolina. To be in this totally different world and yet feel that connection to this shared trauma, this shared history, and then trying to make sense of all of that. And you can feel the connections that he's making to these different places. They're wildly different geographic locations but he's pulling these threads through.

Minisode: A Whitney curator on how a painting by Eldzier Cortor found its way into the collection

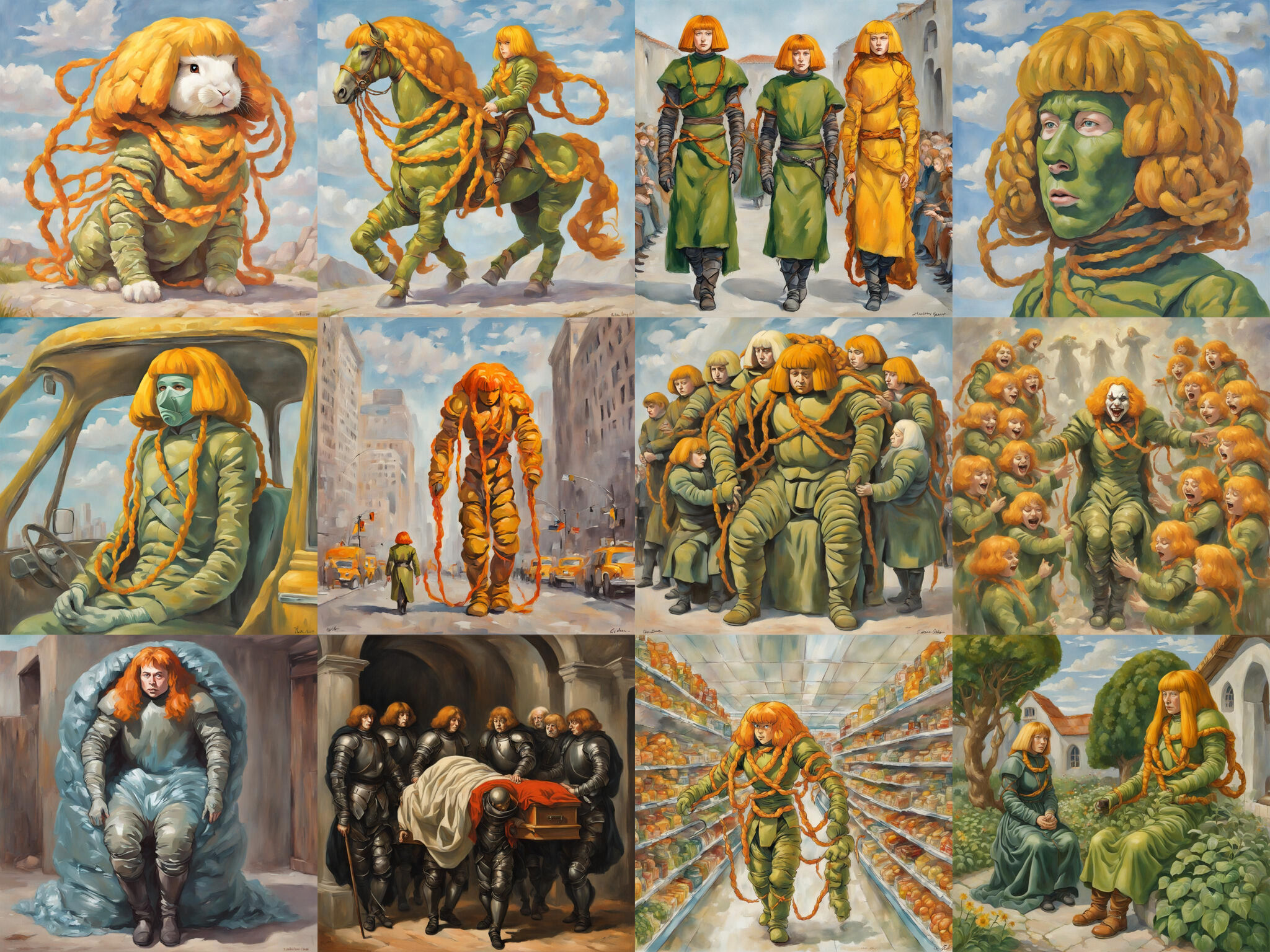

2024 Whitney Biennial Artist Holly Herndon in conversation with Whitney Youth Insights Leaders

Minisode 16

In this minisode, teens from the Whitney's Youth Insights Leaders program interview 2024 Biennial artist Holly Herndon. The conversation explores how the artist's identity and creative process are influenced by artificial intelligence (AI). They talk about the ethical use of AI, if AI can elicit an emotional response to art, and the evolution of the art world to include machine learning models as an art form. Visit the Whitney's portal to Internet and new media art, artport, to enter Holly Herndon and Mat Dryhurst: xhairymutantx, a project that focuses on training data behind AI models, opening new possibilities for its use.

Know a teen who might be interested in the Whitney’s programs? Learn more and apply now.

Released August 13, 2024

0:00

Minisode: Biennial Artist Holly Herndon in Conversation with Whitney Youth Insights Leaders

0:00

Teen Narrator:

Welcome to a special minisode from the Whitney. I’m one of the Youth Insights Leaders, part of an after school program where we work with artists in the Museum’s exhibitions. For this year’s Biennial, we interviewed one of the artists in the show.

Holly Herndon:

My name is Holly Herndon and I'm an artist.

Teen Narrator:

We talked to Holly about her art, which she makes with her husband Mat Dryhurst.

Holly Herndon:

So we created this model that is hosted on artport that you all can play with.

Teen Narrator:

artport is the Whitney’s internet art portal. When you open Mat and Holly’s project up, you see a box to enter text. Below that, there’s a grid of AI-generated images. The pictures are mostly people and other creatures with long, ropey, orange braids and thick bangs. A lot of them are wearing puffy green suits. Most of them are female. They’re kind of like distorted versions of Holly. When you play around with their work in artport, you get more of these AI-generated images.

Teen Narrator:

Sometimes they’re a little off. Like we asked for a claymore, and it was just a regular sword. And the program didn’t seem to know what a Mega Chad is.

Holly Herndon:

I'm trying to change who I am in public AI models, what my embedding is in public AI models. An embedding of a bottle would have a bottleness—like an essence or a certain bottle-like quality that we kind of all as humans understand is the core essence of a bottle. And then to extrapolate from that, when you get to more abstract concepts, that gets more and more blurry and gray. And so we were able to actually do some reverse engineering and look at my embedding, and it really turns out that I'm kind of like this just blob of orange hair and bright blue eyes. These models are trained on the open internet. So any images of me that are tagged with my name, that's basically what creates the concept of me in these models. And the way that these systems work is I actually don't have any control over who I am. It's just this kind of aggregation of images that other people have uploaded. So I was kind of asking myself, "How much agency can I have in this system? What can I do with it to push back on this a little bit?"

So I made a costume with a giant haircut. So I basically just turned myself into my pastiche, just turned myself into my haircut. And then we made a model that people can navigate on the artport site. The data that goes into it is kind of ranked according to trustworthiness of the source because going back to the original idea of trying to find this objective truth, even though that's of course a very, very problematic thing to try to reach, but that's how these systems work. So anything that shows up on Whitney.org is going to have a higher ranking than something that's on my random blog spot somewhere. So then the next time that a model is created, we have to kind of wait and see, but we're thinking that my public embedding will be infected with this kind of character that we created.

Teen Narrator:

We asked Holly about what kinds of creativity she could express using AI.

Holly Herndon:

Every project that I've done with AI has been extremely manual. It's not just some automated process where it's type in a few words and art is done. It's usually very laborious, many decisions made. I think there's this perception that it's this fully automated thing, and it can be for some people, but for my practice it's really about getting into the bones of the model, understanding the training data, understanding the broader systems that the model is situated in.

Teen Narrator:

We also wondered what she thought about the future of using AI in art.

Holly Herndon:

I think that we're on this precipice of things dramatically changing because media will become kind of infinite and really easy to produce. I think it's going to change how we think about intellectual property, which is basically authorship because these systems are inherently collaborative. So you can collaborate with other people directly, but you can also collaborate with the entire human history, which is kind of a weird thing to wrap your head around.

So I think it asks us to question some of the things that we take for granted from a 20th-century approach to artmaking. I think it puts everything in question. I think that's really exciting. I think we're going to see artists using machine learning models as an art form. Whereas painting is a category, I see models as a category because they're these kinds of worlds that are infinitely navigable and generative that you can create a world and your audience can then create work through you or with you and kind of dive deep into your world in a really interactive way. And I think that that's very rich territory for artists.

That approach of humanizing these really technical systems has been there from the beginning of my practice, and I hope that it remains and I think that it remains. I think a lot of the things that we talk about with the work is a focus on the training data and a focus on how these systems aren't these alien intelligences, but they're just like aggregate human intelligence. It's actually a really remarkable human accomplishment, AI. I don't see it as this alien accomplishment. It's like us all together, and that's something to be celebrated if we can see the kind of humanity in it.

Teen Narrator:

Artists Among Us Minisodes are produced at the Whitney Museum of American Art. This episode was produced by teen Youth Insights Leaders: Hale, Kiyan, Jinhaohan, Gabryellah, Brigitte, and Sahara. Production support was provided by Whitney staff.

Minisode: Biennial Artist Holly Herndon in Conversation with Whitney Youth Insights Leaders

2024 Whitney Biennial Artist Kiyan Williams in conversation with Whitney Youth Insights Leaders

Minisode 15

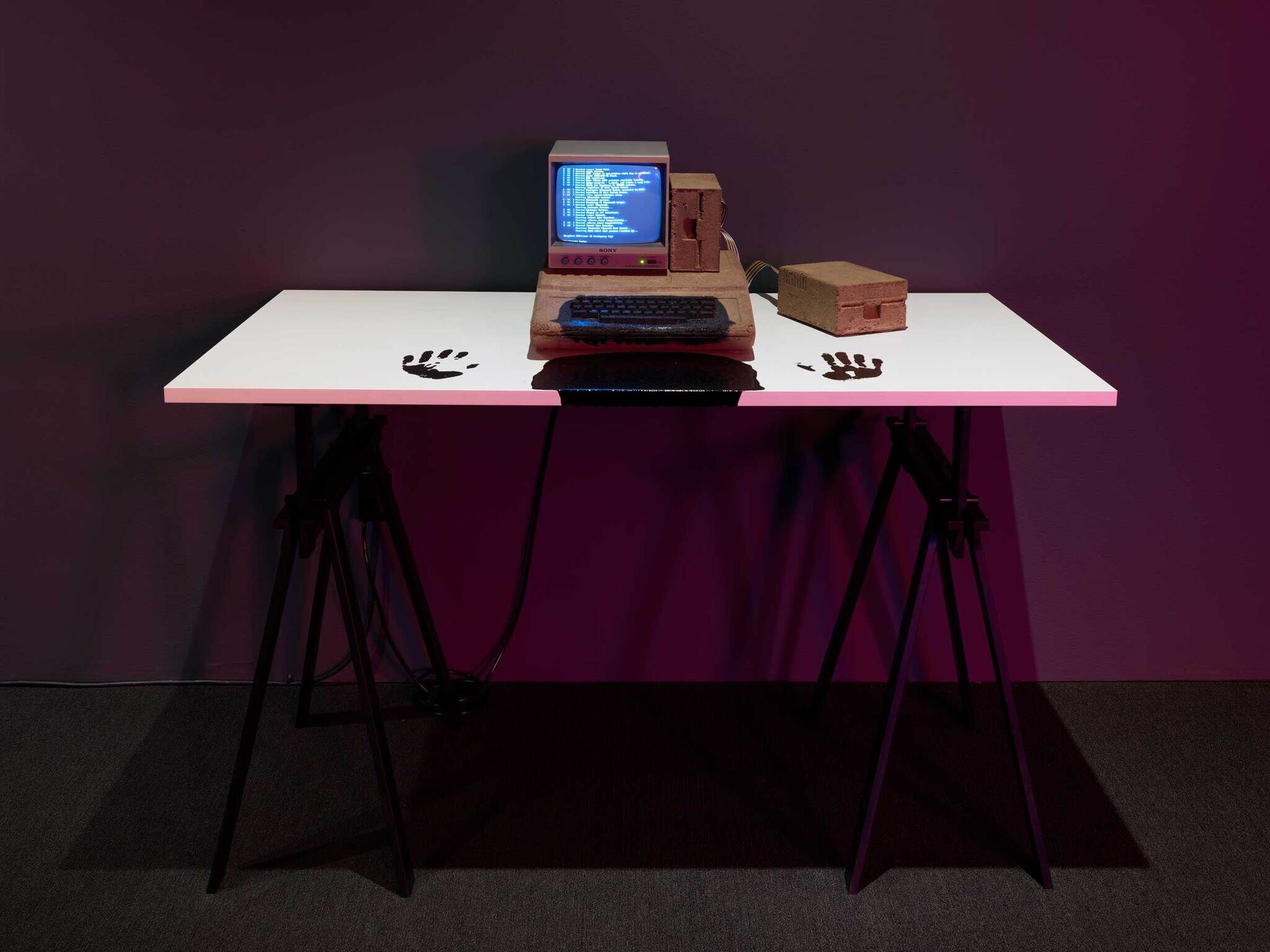

In this minisode, teens from the Whitney's Youth Insights Leaders program interview 2024 Biennial artist Kiyan Williams. Williams has two artworks in the 2024 Whitney Biennial: a large sculpture of a neoclassical building made of brown soil that appears to be sinking into the ground, and a shiny chrome sculpture depicting the gay rights activist Marsha P. Johnson. The teens talk to Williams about what the sculptures mean especially when seen together and at this particular moment in time.

Know a teen who might be interested in the Whitney’s programs? Learn more and apply now.

Released August 5, 2024

0:00

Minisode: Biennial Artist Kiyan Williams in Conversation with Whitney Youth Insights Leaders

0:00

Teen Narrator:

Hi! Welcome to a special podcast minisode from the Whitney. My name is Sia and I’m a Youth Insights Leader, along with Renata, Celise, Alannah, Sasha, Kathleen, and Zuzu. We’re part of an after school program where we work with artists in the Museum’s exhibitions. For this year’s Biennial we interviewed artist Kiyan Williams about their two sculptures on the Museum’s terrace.

One sculpture is a huge, slanted, neoclassical building covered in medium brown soil. It almost looks like it’s sinking into the terrace’s floor, and sticking out from the top of it is an upside down American flag that waves in the wind. Nearby, on another part of the terrace, there’s a chrome sculpture of the gay rights activist Marsha P. Johnson. She’s close to life-sized and faces the larger earth-covered work.

When we spoke to Williams, we wanted to know why they put these two sculptures together.

Kiyan Williams:

My name is Kiyan Williams. My pronouns are they/them/theirs, and I am an artist in the 2024 Whitney Biennial.

These two sculptures—one a neoclassical building that appears to be sinking into the earth and a cast aluminum sculpture of a historic figure—stand in opposition to each other. And what I would describe as different formulations or articulations of symbols of power. Upon a closer view, the viewer sees that the structure is built primarily of cracking earth, of various shades of earth tones, all of which I made by hand by the way.

Teen Narrator:

Reflected in Marsha P. Johnson’s shiny silver surface is the other, larger sculpture, which is actually called Ruins of Empire II or The Earth Swallows the Master's House. It was modeled after the front of the White House.

Kiyan WIlliams:

I'm always just thinking about the kind of mess that is America in this contemporary moment, and always thinking about how I can make more visible or refuse or critique what is happening in America. Upon arriving on the terrace, one encounters the facade of a neoclassical building that is slanted fifteen degrees to the right with ionic capitals, which is the specific design of flourishes that are at the top of the columns.

Teen Narrator:

I noticed Williams was very careful to use the words “land” and “earth” when referring to materials instead of dirt or mud.

Kiyan WIlliams:

The reason why I use land and earth is in some ways that's how I'm framing that I'm speaking to this art historical movement and discourse.

I first was introduced to land art through the work of an artist named Ana Mendieta, who is known for making these earth/body works wherein she immerses her body into a physical landscape and does performances within environments and documents it through photo. I largely encountered art previously through, no shade to these people, painters and sculptors or traditional painters. And so encountering Ana Mendieta's work opened up this whole new possibility of what art could be and what materials you could make art out of.

Teen Narrator:

We noticed their long acrylic nails that they would occasionally tap on the table.

Kiyan Williams:

I will describe my nails. They are coffin-tip, acrylic, see-through, brown, with a chrome outline, that I got done specifically to match the sculptures on the terrace. So the brown earth, with the brown matching the earth, the chrome to match the chrome. And in addition to punctuating my speech with them, I also built that sculpture with them. So they also have kind of functional tools or extensions of my hands. And I use them as tools, as extensions of my hand to push things around, grab things.

Teen Narrator:

Earth is actually a material that Kiyan Williams used in other artworks before.

Kiyan WIlliams:

One of the things I love about working with earth is that I think of it as a collaboration in a sense that the material has its own agency and response to weather and other conditions. I often think about the earth as holding history of a site, of a specific place. Ideas of belonging, what does it mean to belong to a country, for example, whose very existence is precipitated on the oppression of your people? So those kinds of questions are embedded in my use of earth. I think about the earth's capacity as a catalyst for the cycles of decomposition and decay and regeneration—that things go back to the earth to be broken down and repurposed and reconstituted to become something else, so it becomes a metaphor. I like the way it feels in my hands when I'm sculpting with it.

Teen Narrator:

And what about the slant of the sculpture here in the Biennial?

Kiyan Williams:

The slant is specifically fifteen degrees off axis, the slant for me is significant because when it's fully realized, it makes it look like the building is sinking into the ground and off axis. But I also realized recently that what I enjoy about the tilt or the slant is that there's a way . . .

Teen Narrator:

They were taking their water bottle and showing us the fifteen degree slant with it…

Kiyan Williams:

. . . even if I took this and put it upside down, it's like, okay, now it's upside down. The act of twisting something, bending it, taking it off its axis, it does a couple of things—it destabilizes it. Typically I'm taking these structures of power and dominance and tilting them off axis to destabilize them of their power. And I think there's a kind of magic in it. It's like, "Wow, how is this thing standing up and it looks like it's toppling over?" And then recently I came up with this realization that, oh, it kind of reminds me of when I'm standing and I'm standing with part of my weight on my hips, as opposed to standing straight up. And so there's a way in which it mirrors the way I hold my body and what I would call Queer embodiment: hand on hips, being off axis a little bit. I'm like, oh, that's how I move through the world, off axis, but on balance.

Teen Narrator:

So, we wanted to know about the second sculpture. Marsha P. Johnson was a Black trans activist and artist and one of the founders of the modern gay rights movement. She participated in the Stonewall Uprising in 1969, and lived much of her life in the Village and the Meatpacking District in downtown Manhattan, near the Whitney’s current site.

Kiyan Williams:

One thing I'm always interested in is I think a lot about the history of a particular site. And so as I was walking around, I started to think about the history of this neighborhood, the Meat Packing District—who lived here, who made a life here, who hung out here before it was gentrified. And because I studied history in college, I was very aware that this neighborhood used to be predominantly where artists, where Black and brown queer and trans people congregated.

And once I kind of got down that line of thinking, I was like, "Oh, this project that I had already been thinking about, making a monument using Marsha P. Johnson as a subject. And it just kind of clicked. It was like, "Oh, this used to be her hood, she used to hang out here, she used to be in these streets." And unfortunately she was found in the Hudson River.

I do think of her as a witness. So in many ways she's bearing witness to the kind of ruination, the sinking of the structure, but she's also witness to the people who are looking at the structure. So as they're having their moment and taking selfies, she's just on the side watching everything. Conceptually Marsha's title, Statue of Freedom, references a historic bronze monument that's on top of the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, DC. And so in me naming her after this historic bronze monument, I'm really kind of proposing that Marsha is a more ideal embodiment of American values and that she should be a replacement for this statue called Statue of Freedom, in Washington DC.

Teen Narrator:

Marsha P. Johnson is holding a sign in WIlliams’ sculpture that says “power to the people”. This specific image of her was actually captured by a photographer named Diana Davies, who documented Johnson at a protest.

Kiyan Williams:

And I remember in high school, I encountered this photo of Marsha that was taken by this photographer. And she was just chilling against the wall at a protest, smoking a cigarette. And it was something about this image that spoke to me so deeply. And that has been a source of inspiration since I was probably seventeen.

Teen Narrator:

Usually, historic American monuments put figures up on high pedestals. Williams didn’t want to recreate that style for their depiction of Johnson. She stands at average height on a low platform.

Kiyan Williams:

I wanted Marsha to be human scale because I think that in many ways when someone is put on a pedestal, like a figure, it dehumanizes them.

I didn't want to recreate that sense of spectatorship with Marsha because she was the people, she was in the streets, she was on the ground, she was one of us. And so those were the reasons why I made her human scale, not on a pedestal. I came to aluminum because I wanted there to be this reflective aspect where you look at Marsha, but you also see glimpses of yourself and the world around you.

Teen Narrator:

They said that to them, Marsha P. Johnson was the architect of movements against police violence, which has taken many forms. And they see the Black Lives Matter movement as stemming out of her work and her life too. Right, and so we have this person whose life was so impactful, looking out onto this sinking building that looks like a White House. It really tips the scales of what have traditionally been symbols of power. Williams reflected on the earth work again.

Kiyan Williams:

I will say that the scale is the largest thing I ever made in my life, and it was the hardest thing I ever made in my life. It's huge, it's like twenty-one feet high, it's 6,000 pounds, there's a twenty-foot by twenty-foot earth installation around it.

And so I think this work is a clear, or a more, I've gotten better as an artist from when I made this work, to the last work I made. I did my big one.

Teen Narrator:

Artists Among Us Minisodes are produced at the Whitney Museum of American Art. This episode was produced by Renata, Celise, Alannah, Sasha, Kathleen, Sia, and Zuzu. Production support was provided by Whitney staff.

Kiyan Williams:

It's just one of those things where people are like, oh my God, how do you do anything with your nails? And I'm just like. Literally, and I just pull up a picture, I'm like this, I built that with these nails.

Minisode: Biennial Artist Kiyan Williams in Conversation with Whitney Youth Insights Leaders

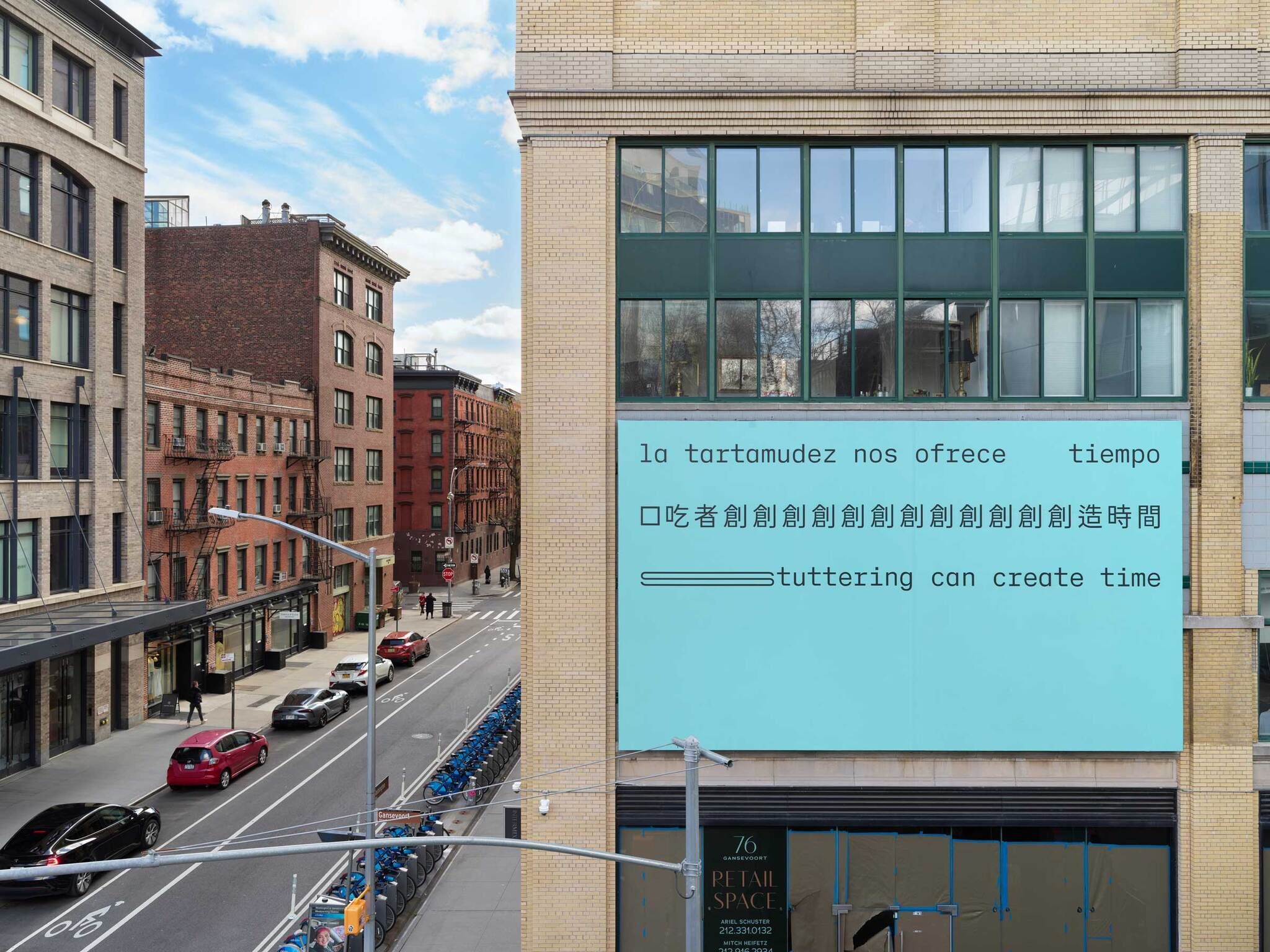

People Who Stutter Create on their 2024 Whitney Biennial Artwork

Minisode 14

Today we hear from five artists who together form the collective People Who Stutter Create. For their contribution to the 2024 Biennial, the group mobilized the Whitney’s exhibition billboard at 95 Horatio Street, across the street from the Museum and the south end of the High Line. The artists, all of whom stutter, created a public artwork that celebrates the transformational space of dysfluency, a term that can encompass stuttering and other communication differences. In this minisode, we hear from all five artists about their artwork titled Stuttering Can Create Time.

Released July 30, 2024

Jia Bin

Delicia Daniels

JJJJJerome Ellis

Conor Foran

Kristel Kubart

0:00

Minisode: People Who Stutter Create on their 2024 Whitney Biennial Artwork

0:00

Narrator:

Welcome to Artists Among Us Minisodes from the Whitney Museum of American Art. For us, this spring and summer are all about the 2024 Whitney Biennial. Over the course of the exhibition, we’ll be sitting down with some of the artists to talk about their work and what it means to be making art in the present moment.

Today we hear from five artists who together form the collective People Who Stutter Create. For their contribution to the 2024 Biennial, the group mobilized the Whitney’s exhibition billboard at 95 Horatio Street, across the street from the Museum and the south end of the High Line. The artists, all of whom stutter, created a public artwork that celebrates the transformational space of dysfluency, a term that can encompass stuttering and other communication differences. In this minisode, we hear from all five artists about their artwork titled Stuttering Can Create Time.

JJJJJerome Ellis:

Our group is called People Who Stutter Create and we are five people who stutter who have come together to create a billboard at the Biennial. I'm JJJJJerome Ellis and I feel so lucky that I have been able to collaborate with these these four amazing people over these past few months.

Kristel Kubart:

So my name is Kristel Kubart. I'm a speech therapist. I live in New York City and I'm a very proud person who stutters. It hasn't always been that way, I used to be very ashamed of my stuttering but helpful speech therapy and being a part of the stuttering community completely changed all of that when I heard that maybe it's okay to stutter and just have it be a part of how you speak.

Conor Foran:

My name is Conor Foran. I'm an Irish practitioner based in London and I work across art and design and a big part of that is stammering. So I kind of use art and design for stammering activism.

Delicia Daniels:

My name is Delicia Daniels and I’m in North Carolina. I would have to say that stuttering appeared for me out of the blue, so to speak, in middle school. And I had to train myself to just talk slowly because, you know, I was ashamed of it, I wasn't used to it. And so every single person on this panel, you know, gave me the opportunity to, you know, to welcome new energy and new vibes around stuttering and around scholarship connected to celebrating words that repeat.

JJJJJerome Ellis:

Hi, Jia, welcome!

Jia Bin:

Hi hi JJJJJerome! I am—compared to all the leaders in this group—I would say I am newer. I was born and grew up in China. Stuttering had always been my big biggest shame growing up. Everything I do is trying to hide hide my stuttering throughout my entire life. It's it's been a journey. I'm I'm just so so thrilled that that my my biggest shame seems to have become my biggest blessing.

Conor Foran:

So the billboard is basically three lines of text that hang from the top of the billboard and it's in Spanish, Chinese, and English. And in English it reads, “stuttering can create time.” And and the text is all black and it's on on a kind of a calm green background I would say. And in terms of the design decisions that went into it, we used my typeface, Dysfluent Mono, which emulates or represents stammering in typographic form. So the Spanish has a gap, and the Chinese repeats, and the English is stretched. So that was us kind of representing each form of stuttering essentially. So I think overall it's stammering pride coded. It doesn't say "stammering pride" but but you can definitely get that from the billboard. And yeah, just on the color as well—we wanted to add some kind of color. By adding this green—the color green has been used by the stammering community for years and years and years as a point of representation—we thought that maybe that would be the most appropriate. And it gave the billboard a bit more color and a bit more warmth and a bit more vibrancy.

Kristel Kubart:

I know people will listen to this who don't know that much about stuttering. So repetition is when the first couple of sounds repeat like, just like that. Prolongation is when the sound gets stretched like that. And a block is when a person experiences a lot of tension and just no sound is coming out. So those are the three types of stuttering that we represented on the billboard. And then in those moments, sometimes people who stutter have to make a choice, you know. Are they going to let the stuttering out? Are they afraid to stutter in that moment? And they might try to switch words or, you know, pretend they forgot what they were going to say. So that's why this idea of stuttering pride can be so powerful—you're actually saying what you want to say even if it comes out, you know, repeated or long like that.

Conor Foran:

And also I forgot actually to say that the bottom half of the billboard is completely empty, which some people might be wondering why we did that, because it's like, we’ve been given this really huge space, but our statement only takes up a bit of it. But we did that intentionally because it does play with this idea of pauses and hesitations and expectations.

Delicia Daniels:

Working in a public space I think is important and essential because a lot of times people who stutter feel unseen and unheard. And I feel like this platform, you know, raises the volume for people who, you know, tend to, you know—I used to sit in the back, and I'm quiet, don't say much, and be very brief. You know, as I feel something coming on, I'll stop.

Jia Bin:

This is something new but at the same time the power I think the power of of the the visuals and the power of art will trigger some discomfort, maybe, in the people who stutter who are still on the journey of moving towards acceptance and maybe the public would say, “Why?! You know, this is the worst thing to be put out there.” So I feel like this is a very loud way, even through the silent words, to put the message out.

JJJJJerome Ellis:

I'm I'm moved by the way that that that that that that all of y'all throughout the process have have had such such care careful attention to the weight of each word. As as as you're saying, Delicia and Jia, about the volume. And it has personally helped me think about this experience that that many people who stutter have on a daily basis—feeling like they are wasting time or taking up too much time or not communicating in the amount of time that is allowed, you know.

Jia Bin:

So when we were doing our discussion, we also mentioned how it takes two to stutter from the listener’s perspective. Like stuttering creates time not just for the people who stutter perspectives, but from the listener’s perspective too. We we open the space, we we create time for the listeners, invite them to our communication styles, invite them to become better listeners—deeper listeners—to build this human connection through a unique way of communicating.

Kristel Kubart:

Personally, I'm just so excited about the fact that there's going to be a stuttering billboard. It warms the heart to know that it will be seen, that it will challenge people’s ideas about stuttering because stuttering is something that is still very stigmatized and not very well understood. And I think the billboard kind of poses a new way of looking at stuttering and it's going to create a lot of conversations about stuttering in places that normally wouldn't exist.

JJJJJerome Ellis:

I'm glad. Yeah, I'm I'm I'm glad that that that it all feels good for everybody and I and I could not be more, just more grateful and lucky to, you know, just to be a part of this this group of amazing people.

JJJJJerome Ellis:

I just wanted to also honor the work and creativity of Zoe (Yu) Cui who helped us as the typography consultant.

Jia Bin:

Oh, I do want to add one more name—Angelica Bernabe. She she helped us with with with the Spanish translation as well.

Narrator:

Artists Among Us Minisodes are produced at the Whitney Museum of American Art by Anne Byrd, Nora Gomez-Strauss, Kyla Mathis-Angress, Sascha Peterfreund, Emma Quaytman, and Emily Stoller-Patterson.

Minisode: People Who Stutter Create on their 2024 Whitney Biennial Artwork

Maja Ruznic on her 2024 Whitney Biennial Artworks

Minisode 13

Today we hear from Maja Ruznic about one of her two paintings in the Biennial. She talks about finding beauty in sadness, her path to becoming the artist she is today, and the restorative power of awe.

Released May 30, 2024

0:00

Minisode: Maja Ruznic on her 2024 Whitney Biennial Artworks

0:00

Narrator:

Welcome to Artists Among Us Minisodes from the Whitney Museum of American Art. For us, this spring and summer are all about the 2024 Whitney Biennial. Over the course of the exhibition, we’ll be sitting down with some of the artists to talk about their work and what it means to be making art in the present unfolding moment.

Today we hear from Maja Ruznic about one of the two paintings that she has in the Biennial, called The Past Awaiting the Future/Arrival of Drummers. The painting is huge, over twelve feet wide, and more than eight feet tall. Figures and shapes painted in rich seductive colors move in every which way across the crowded canvas. Here’s Maja Ruznic:

Maja Ruznic:

My name is Maja Ruznic and I'm a painter and I live in Placitas, New Mexico. I don't normally work in this horizontal orientation. Usually, my paintings are smaller than this kind of giant format. My palettes are colorful and I'm really in love with highly pigmented color. So having something like a cadmium red light right next to a cobalt green turquoise, it's supposed to make your eyes almost have a seizure. So I'm really interested in color level and how color can operate and have encoded meaning that is not available to our rational mind.

And I really believe that through our senses and when our body is really affected, great changes can happen. And I think that's why people like to go to cathedrals, even if you're not religious, or mosques, there's a sense of awe that can fill the body. And I know there's a lot of research about how awe is a very restorative and opening emotion and how we need it as a species and how it differentiates us from other species. So the kind of awe I like to create with color and form and figures like this female figure here who is both crying, but she's also in a way the most powerful. She's the only one confronting us.

I think my history has colored me in a certain way where I have certain preferences and I think sadness is the one thing that my body has remembered and I've learned to love. I find beauty in sadness and I do think that has a lot to do with my background. I don't know if I would have the same love for all things full of pathos if I had a different upbringing.

Narrator:

Ruznic grew up moving from country to country after she and her mother fled Bosnia when war broke out when she was a child in the 90s. Eventually, they landed in San Francisco.

Maja Ruznic:

When you think about a conflict, most wars that are fought are often trying to reconcile or undo some past injustice. So that's the war that I fled from. It was the Serbs trying to undo the injustices of the Ottoman Empire. And I think there's something so strange and absurd about the desire to cleanse the past by doing something now that is equally damaging. So there's this sense of constantly pulling the past in order to “fix” or to amend. But I think there's always something dark and violent that arises out of that desire to fix that we may not even be aware of at the time. We can only tell that in the future.

So this piece is really about that. It's thinking about how the past is being dragged and how there are victims of the present that are somehow being used to undo something from the past. Yet time is kind of always marching on. So I think of all the feet in this painting, and most of them are in profile. Some of them are moving to the left, a couple of them are moving to the right, and some of them are facing us. So that was me trying to fuse the sense of all times existing in this one plane, collapsing the sense of actual moving time, and freezing it in this moment.

I think my figures if you really look at their expressions they're quite sad and things have happened to them, but they're survivors. They're kind of these wounded healers who are only as powerful as they are because of the stuff they went through. In alchemy, they talk about the transmutation of materials. The alchemist works on that in their lab to get to the gold. In Jungian psychology, they talk about all the different stages that your psyche needs to go through in order to achieve this kind of unified state. And I think I as a person and I as a painter am working that out as I paint. I'm constantly trying to make something moving for others out of these sad little parts that are inside of me.

Narrator:

Artists Among Us Minisodes are produced at the Whitney Museum of American Art by Anne Byrd, Nora Gomez-Strauss, Kyla Mathis-Angress, Sascha Peterfreund, Emma Quaytman, and Emily Stoller-Patterson.

Minisode: Maja Ruznic on her 2024 Whitney Biennial Artworks

Cannupa Hanska Luger on his 2024 Whitney Biennial Artwork

Minisode 12

In this minisode, we hear from Cannupa Hanska Luger about his Biennial artwork that takes the form of a tipi inverted and hung from the ceiling of the gallery. But Luger lets us know that, "The tipi is not upside down. The tipi is actually in the right positioning, in right relationship, in a right way in the world if the world isn't as upside down as it is presently."

Released May 22, 2024

0:00

Minisode: Cannupa Hanska Luger on his 2024 Whitney Biennial Artwork

0:00

Narrator:

Welcome to Artists Among Us Minisodes from the Whitney Museum of American Art. For us, this spring and summer are all about the 2024 Whitney Biennial. Over the course of the exhibition, we’ll be sitting down with some of the Biennial artists to talk about their art and what it means to be making art in the present unfolding moment.

Today we hear from Cannupa Hanska Luger about his Biennial work. The piece takes the form of a tipi inverted and hung from the ceiling of the gallery. It's made of a translucent material in rich pinks and burgundies and looking up at it from below has a kaleidoscopic effect. He mentioned to us that he uses the word tipi both literally, and as an acronym for Transportable Intergenerational Protective Infrastructure. He coined the phrase but said that “the phrase has always been what a tipi is in one way or another.” Here’s Cannupa Hanska Luger:

Cannupa Hanska Luger:

My name is Cannupa Hanska Luger. I am Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, and Lakota. And an enrolled member of the Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold. And I'm a ceramic artist. I have a background in ceramics anyway, and I do a lot of mixed media material.

The piece is called Uŋziwoslal Wašičuta, a Lakota phrase that says, “the fat-takers world is upside down.” There are aspects of this piece that are embedded, there are aspects that are visually experienced, and then there are concepts that with Indigenous knowledge or upbringing there's a deeper understanding of some of the work. But what you physically see is a tipi, full-sized, constructed out of crinoline which is a mesh material. So it has a transparent aesthetic to it. The skin surface is a hot pink and a black. It has trim and structural components that are made out of nylon ribbon.

We've inverted the tipi and presented it from the ceiling pointed down. It's got a strong physical space, you get this tension of the tipi’s inversion overhead. And I think that imposes certain sorts of tensions that we have trouble describing presently. And really just thinking about the weight of Indigenous knowledge on our present culture, present community, our present world being inadequately described and demeaned through erasure and omission redaction from our history lessons. It allows the scale and the weight of that to impose the room in a way that we haven't been allotted presently.

There's a model in physics around the space-time continuum, and it's two cones that invert and it's like a geometric model of the space-time continuum that is embedded in the tipi and its form and its purpose from a long time ago. It is a lens. It's often times described as a lens that recognizes the entire universe and the place that we stand being the same.

I'm interested in how we present a future look that isn't saying, "This is the way the future is going to go,” but “this is a way that the future doesn't narrow into a point that it actually expands in the other direction.” So what we're imagining today potentially and probably will become our distant future realities. And so recognizing that trajectory, that gives you a little bit of agency in time. "What do I want to carry from my past thinking about ancestral knowledge? How do I reassert that in the present by imagining its application in the future?" So this allows me to imagine futures that I'm actively participating in its creation presently by gathering information from the past.

I also see the tipi being co-opted by Artsy and Etsy and all of these different components that diminish the actual importance and the power of the tipi where you can get tiny versions of it for your children. You can get tiny versions of it for your dog. There are all of these iterations of that form. It is a form that you see repeated across the globe in different ways. But I think it's really important to understand the wholeness of its design outside of its form. And that access to the tipi should be an exchange and a recognition of all of the context, then you enter a tipi with the same level of humbleness. So presenting the tipi in a way that you cannot access it is a part of that conversation. So as an artist, I'm like, "Well, how do you present this work? Share that knowledge, but not slip into providing total access?" And so presenting it with this crinoline material, it allows you to see into that space but never actually physically be inside of it.

But then by inverting it and putting it on the ceiling, I can express that the present we are in is upside down. The tipi is not upside down. The tipi is actually in the right positioning, in right relationship in a right way in the world if the world isn't as upside down as it is presently. And so it could be accessible, but we need to flip everything that we value and consider as value in our world. The leap that we need to experience is like, "Oh, the tipi is not upside down. I'm upside down. Everything here is upside down." That's actually in right relationship.

Narrator:

Artists Among Us Minisodes are produced at the Whitney Museum of American Art by Anne Byrd, Nora Gomez-Strauss, Kyla Mathis-Angress, Sascha Peterfreund, Emma Quaytman, and Emily Stoller-Patterson.

Minisode: Cannupa Hanska Luger on his 2024 Whitney Biennial Artwork

Dala Nasser on her 2024 Whitney Biennial Artwork

Minisode 11

In this minisode, we hear from 2024 Whitney Biennial artist Dala Nasser. Her work is titled Adonis River and she made it along the banks of that river, now called the Abraham River on Mount Lebanon north of Beirut. The work tells the ever-evolving story of that place and its namesake.

Released May 7, 2024

0:00

Minisode: Dala Nasser on her 2024 Whitney Biennial Artwork

0:00

Narrator:

Welcome to Artists Among Us Minisodes from the Whitney Museum of American Art. For us, this spring and summer are all about the 2024 Whitney Biennial. Over the course of the exhibition, we’ll be sitting down with some of the artists to talk about their art and what it means to be making art in the present unfolding moment.

Today we hear from Dala Nasser. Her work in the Biennial is titled Adonis River. The work is a space created from tall wooden structures—columns and cubes—draped with heavy fabric. The fabric is covered in rubbings taken from rocks at the Adonis Cave and Temple and then the material was dyed using iron-rich clay from the banks of the nearby Abraham River on Mount Lebanon, north of Beirut. Although it is now called the Abraham River, it was once called the Adonis River. Here is Dala Nasser.

Dala Nasser:

My name is Dala Nasser. I'm a material and process-based artist. Essentially the story of Adonis and Aphrodite is based on Sumerian history. So in ancient Sumerian tablets, there was a story of the goddess of fertility and her mortal lover and his untimely death and the mourning practices that developed throughout the region commemorating this sort of loss. And it moved on from Sumerian culture to Babylonian to Assyrian and to what you know now as Adonis and Aphrodite. So the names started to change as time moves by. So my interest in the story itself is how it's timeless and how it's morphing slowly and slowly.

And for me the interesting thing around this is the location of this tale in a cave in Mount Lebanon. Every spring as the snow melts off the top of Mount Lebanon, it goes through this cave and out into a river. The reason why they called it Adonis's River is that every spring, when the water would come gushing out as the snow melts, the water levels rise and mix with the very iron oxide-rich soil of the area. The river takes on a bit of a red hue. So the locals and everyone around the river would say that this river turns red with Adonis's blood.

I took fabric to the cave and the temple and I produced charcoal rubbings on site on the rocks of both of the locations. And after that, I dyed them with iron oxide-rich clay that's made out of the soil that surrounds the river. And the final step was I washed them in the river. When I started working the way that I work, which has now been, I don't know, over ten years now, it developed from just a very basic idea where I was sick of doing drawings and I knew exactly how I wanted them to end. And I thought to myself, how can I produce work that keeps changing beyond the artist's hand?