Minisode: Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the Last Gullah Islands

Dec 4, 2024

0:00

Minisode: Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe and the Last Gullah Islands

0:00

Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe: I am Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe, and I have been photographing since a little over fifty years now. I became interested in the Gullah culture when in college I did a six-month independent study from school on the west coast of Africa. And on my first morning walking out of the student hostel, coming out and looking to my right and looking to my left on the street, I just noticed all I saw were Black people. And that experience was one of, "Wow." It created for me an experience that immediately took me back to growing up in my own African-American culture and in my community that I connected immediately.

I'd always had an interest in showing the Black community, my community, in its joyful and celebratory and ritual communities that we are and how we celebrate our culture. And when I finally had an opportunity to go to the South Carolina and Georgia Sea Islands, that was in 1977, March of 1977, and I didn't know a lot about the Gullah Geechee culture except that I knew they were direct descendants of slaves.

And coming off of the training of being a street photographer at the school I attended and the teachers that I had at that time, who were remarkable teachers, Gary Winogrand, Joel Meyerowitz, Jay Maisel, Arnold Newman. That experience then made photographing on the South Carolina Sea Islands and the Georgia Sea Islands even more accessible to me because I had that experience of just walking on the street and photographing people.

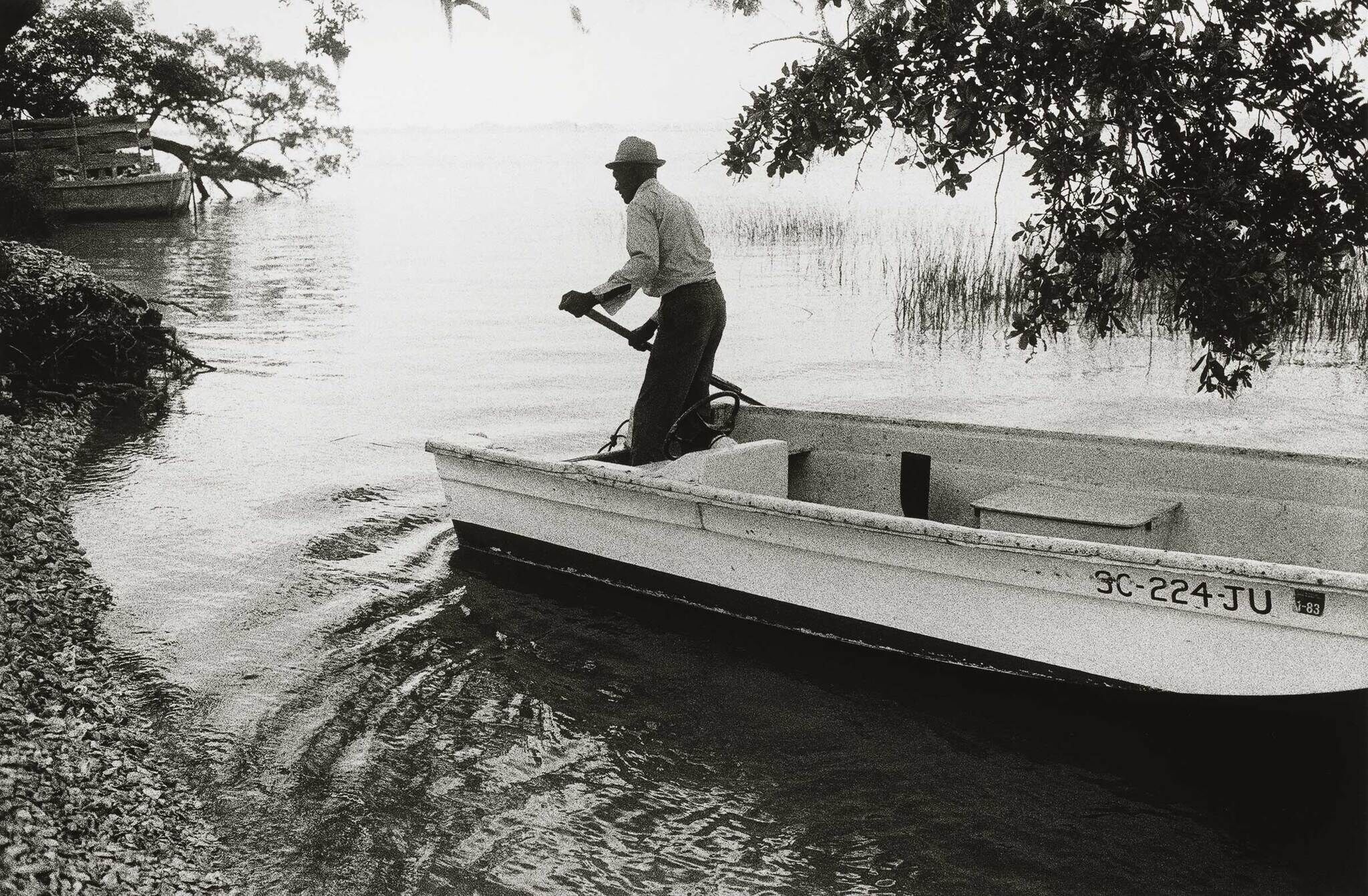

On islands like Edisto and Wadmalaw Island and Johns Island, you could visit these places by getting to the particular islands on a bridge.

But a friend of mine said, "Sounds like you had a great first trip to the Sea Islands. But you haven't been anywhere until you've gone to Daufuskie Island." Daufuskie. It sounded interesting. I did not know at the time that there was no bridge linking Daufuskie Island to the mainland, like all of the other islands I had visited. And when I discovered that, I knew this was going to be someplace special. So I did call her friend who has now become a lifelong friend of mine, and that's Dr. Emory Campbell. And Emory introduced me to a few people. And the one person he introduced me to was the lady that I eventually stayed with on all of my trips to Daufuskie. And the moment that I stepped on Daufuskie Island, I could hear on my very first trip, a language that was spoken that was quietly spoken in a way that maybe I wasn't really meant to hear this language, but it was spoken among the people on the island. But I still received a very warm reception.

And I knew that a lot of people didn't like my constantly taking pictures of them and they would often ask me, "Why are you taking a picture of that? You've already taken a picture of that. Why are you doing it again?"

And then in 1979, Hurricane David came along and it blew down a couple of the structures that I had been photographing. One was an old praise house, a slave praise house, and it was completely blown apart. It was gone. And that's when people were coming to me and saying, "Ah, so that's why you're taking pictures." They began to understand what was happening to their island and what was happening over time. They allowed me the freedom and the generosity and the openness to allow me to come into their lives and photograph them.

So the story for I think many of the Daufuskians and development was as developers started to come onto the island, they were offering what people felt were large sums of money for their land because while the Daufuskians didn't have a lot of money, Daufuskians did have a lot of land. They were a land- rich people, and this is what developers were looking for.

Over a five-year period, I visited Daufuskie on and off the island many, many times, and I stayed with this woman that Emory had introduced me to, and her name was Susie Smith. And without Susie, I don't think I would ever have gotten under the good graces of Blossum, known as Lavinia Blossum Robinson. She was the matriarch of the island. So I was passing by Blossum's house walking on the island one day and walked up to her front porch and she was sitting on her porch, and I knocked on the door, and she invited me to come in, which I did. And I asked her how she was doing, and she was in a pretty good mood that day. So I came in and asked her if I could make a portrait of her. And she kind of shook her head and said, "You've made enough portraits of me." And I said, "But this is special. You're sitting on your front porch and I'd like to just get a portrait of you on your porch. Come on, Blossum."

So I had to coax her into this picture of Blossum's face with this warm smile. And I think the warm smile is saying, "I know you've had a picture of me before. You're taking another one?" But she smiled. She was surrounded on the screen porch by such beautiful light. The shadows, you can see just about all the details in the shadows. You can see the braids in her hair, and you can see the gray of her life and the markings on her face that tell you something about this woman who knew so much and who was so strongly rooted on this island born and died on Daufuskie, and this was her island, the island matriarch.

Blossum knew that change was going to be coming to Daufuskie. They had already started talking about putting in a spa on Daufuskie in a well-known hotel chain, and she was not going to have it. So Blossum was, along with many of the Daufuskians, she pretty much led that charge was very much against development at the time. When Blossum died, I got a phone call from the island to let me know that Blossum had died and I better get down because there's going to be a funeral and I should come. And I did. In a couple of days, I was down on Daufuskie and photographed Blossum's funeral, and people talked about how she would be standing at the dock with her fist in the air keeping the developers away. And having known Blossum, that's exactly what she would've done.