Not on view

Date

2020

Classification

Drawings

Medium

Watercolor, ink, and graphite pencil on paper

Dimensions

Sheet: 23 1/2 × 28 1/8 in. (59.7 × 71.4 cm)

Accession number

2021.72

Credit line

Purchase, with funds from the Drawing and Print Committee

Rights and reproductions

© Kambui Olujimi

Audio

-

0:00

Minisode: Kambui Olujimi on two works made in quarantine

0:00

Narrator: Welcome to Artists Among Us Minisodes from the Whitney Museum of American Art. Today we hear from artist Kambui Olujimi who has two paintings currently on view at the Whitney. His works, Your King Is on Fire and Hart Island Crew, are included in the exhibition Inheritance, up through February.

Kambui Olujimi: My name is Kambui Olujimi, I'm from Bed-Stuy Brooklyn. I'm an interdisciplinary artist and I like to make things. These paintings are part of a collection of works that I'm calling the Quarantine series, because I made them when I was in quarantine during the lockdown of 2020. Both Your King Is on Fire, the triptych, and Hart Island Crew.

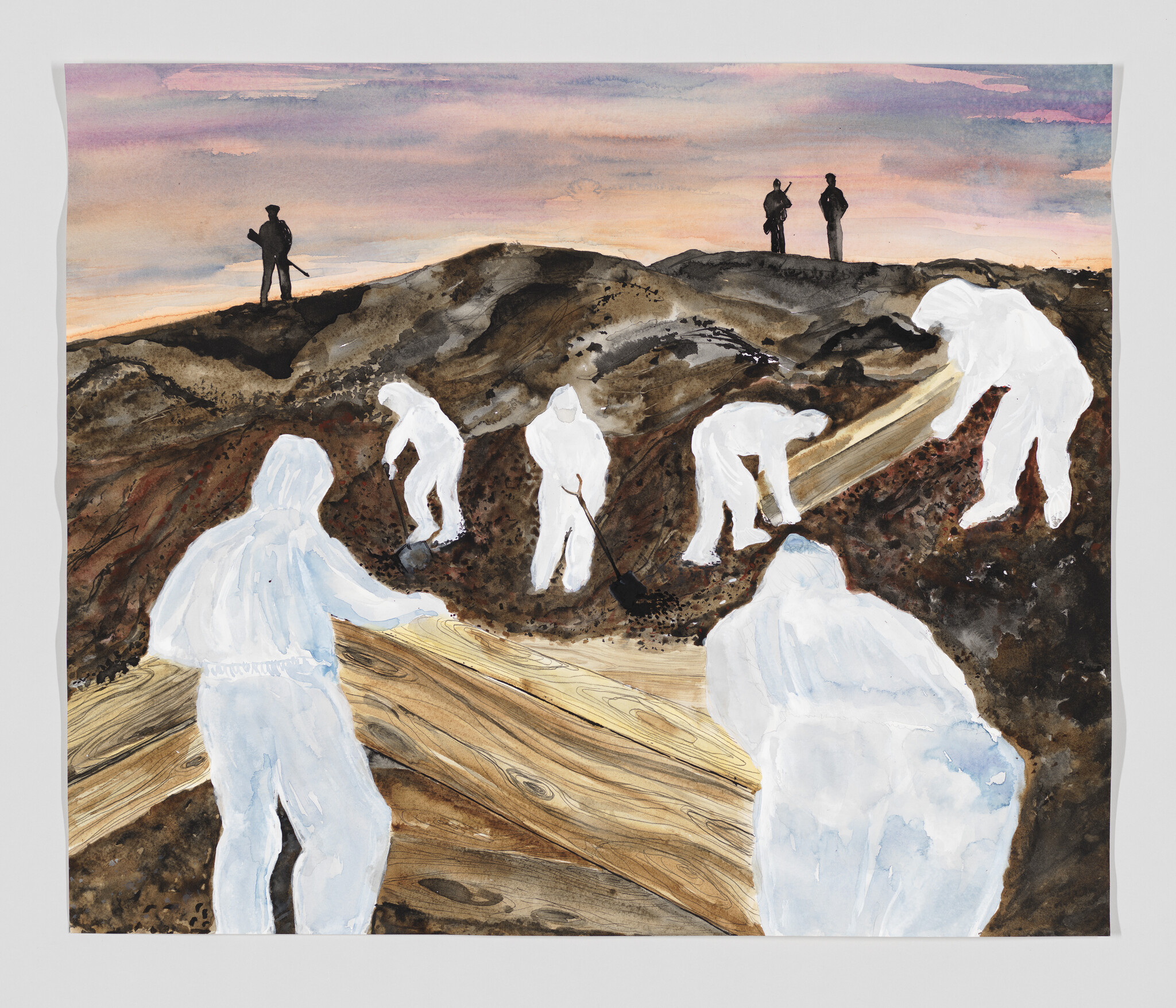

Hart Island is this little island right across from Rikers and for a little more than a century we've been burying the unclaimed dead there. This painting is a horizontal painting that has six figures dressed in white hazmat suits moving coffins around in a mass grave. The grave is open and the landscape is kind of hilly. In the distance, there are a few figures that are silhouetted. Two have guns and two have a kind of cap that reads as a correctional or law enforcement hat. Then in the distance you can see the sun setting over the hill.

So during the pandemic there were these refrigerated morgues that were mobile because New York City had so many fatalities. And so it made me start to think about all of the loss that we were going through and suffering through without having a real space to mourn or to grieve. People weren't allowed to gather. And so it led me to Hart Island because a lot of people were unclaimed. There was maybe not family, or family was in a place where they weren't reachable. And there's a place—pretty much everywhere there's a potter's field is what we call it—where you bury unclaimed dead.

And as I started to do some research on Hart Island, a lot of the labor that was done there was performed by incarcerated folks at Rikers. Over the years, the incarcerated were asked to absorb a lot of this grief. They're the only mourners for bodies that are buried there. So unclaimed dead from the AIDS epidemic, from just living in New York, from crack, from Covid, there are these waves of deaths that happen in any urban space. But in New York, and as a New Yorker in particular, this was my black hole. I feel some kind of way about New York. These are my folks that are unclaimed. And so it started to pick away at me or tap me on the shoulder a bunch.

A lot of the work that I was doing at the time was interior. I was in small spaces. I was thinking about small spaces, and this one is much more expansive. You can see the figures in the far distance, these silhouettes, ominous silhouettes, guards who are holding guns and forcing this process to happen or ensuring beyond choice that this process would happen. And the sky is a sunset, sort of romantic in a classic sense—a romantic sunset that is beautiful. When I was a kid, my mother was big on primary material. So we watched actual firsthand footage when my mother would talk to me and my siblings about history. And I remember being struck one time by footage from a concentration camp being liberated at the end of World War II. There were times when I was like, “but it's just so sunny.” It didn't seem like this could be a thing that could happen on such a beautiful day.

This painting is a tryptic titled Your King Is on Fire. It pictures a statue of King Leopold on fire. King Leopold was the king of Belgium. Belgium was a colonial power and colonized the Congo and did it most brutally. It's estimated that during this period up to fifteen million Congolese were murdered. There's not a lot globally in terms of the response for years around these actions. And it's only recently that it's beginning to be talked about in a wider context, a wider Western context. In Belgium, there have been protests around the sculptures of Leopold for some time.

And so, while in America we were having conversations around Confederate monuments and their removal, you see that this is not just happening with regards to Lee and Christopher Columbus, but also Rhodes and Leopold. And so the lockdown really collapsed space in a way where these struggles that were happening here were having shock waves throughout the globe. And the statue in Antwerp was set on fire and eventually removed.

There was a joy in seeing this sculpture removed for me. There's no way you could ask for redemption in light of these kinds of mutilations. And even as a young person, there's a doom that gets put on you. Because I'm not them, I'm not Belgium, I'm not Leopold, but we are human. And so as a kid, I was very much into space and the universe, and we can make all these artificial lines here on this planet, but you go anywhere in the universe, y'all all just humans. Just like I can talk about being from Brooklyn and how different that is from being from Queens and this and that. But I go to Senegal, I'm an American. I'm an American and they want to know why my country has gun violence on the level that it does. They want to know why my country…and I'm like, “they don't really listen to me like that.”

The further away from home you go, the more that home gets consolidated. And so that's a way of thinking of it now. But as a kid, I was just like, “we are all human and this is what humans be about,” and there's a doom to that. To see that there was a reconciliation, or at least steps towards that, or steps towards taking that myth of the monarch down or chipping away at it, and I mean this specific monarch, it was joyful.

Narrator: Artists Among Us Minisodes are produced at the Whitney Museum of American Art by Anne Byrd, Nora Gomez-Strauss, Sascha Peterfreund, Emma Quaytman, and Emily Stoller-Patterson.

Minisode: Kambui Olujimi on two works made in quarantine

-

0:00

Kambui Olujimi, Hart Island Crew, 2020

0:00

Kambui Olujimi: Mi nombre es Kambui Olujimi.

La Isla Hart es una pequeña isla al otro lado de la Isla Rikers. Muchas personas se olvidan de que Nueva York son muchas islas juntas, un archipiélago. Una de ellas es la Isla Hart, y durante más de un siglo, este ha sido el lugar de entierro para los cuerpos que nadie reclama.

Comencé a investigar acerca de la Isla Hart y descubrí que gran parte del trabajo era realizado por prisioneros de Rikers. A lo largo de los años, los prisioneros de Rikers recibían centavos de un dólar, si es que recibían algo, y tenían la carga de absorber emocionalmente todo este dolor. Son los únicos que duelan a los millones de cuerpos que están enterrados en ese lugar. Cuerpos que nadie reclamó de personas que murieron durante la epidemia del sida, o simplemente por vivir en Nueva York, por consumir crack, de COVID. Son estas oleadas de muerte que suceden en cualquier espacio urbano. Pero en Nueva York, y lo digo como neoyorquino, este fue mi agujero negro. A veces siento este tipo de cosas por la ciudad. Estos son compañeros míos por los que nadie preguntó.

Narrator: Olujimi pintó esta obra en el verano de 2020, durante la cuarentena.

Kambui Olujimi: El hecho de que tengan puestos trajes de protección biológica me da una sensación fantasmagórica. Tienen puestos estos trajes y parece todo muy clínico. Durante la epidemia, se vivió una falta de conexión.

Quería incluir el paisaje para que, como espectador, pudiera sentir que estoy ahí, que me involucro, que puedo sentir las fosas. Y eran muchas las tumbas que se estaban cavando. Fueron tantas durante la pandemia que tuvieron que hacerlas con topadoras, y son fosas comunes en general. Entra esta maquinaria pesada, y no es solo una persona, sino muchas, y llegan y quizá cavan un pozo y luego lo tapan. Transforman la tierra. En definitiva, el paisaje era importante para mí. Además de una sensación de escala y espacio abierto.

Kambui Olujimi, Hart Island Crew, 2020

In Inheritance (Spanish)

-

0:00

Kambui Olujimi, Hart Island Crew, 2020

0:00

Kambui Olujimi: My name is Kambui Olujimi.

Hart Island is this little island right across from Rikers. A lot of people forget, New York is just a bunch of islands, it's a little archipelago. And so, one of them is Hart Island and for a little more than a century, we've been burying the unclaimed dead there.

And as I started to look at some research on Hart Island, a lot of the labor that was done there was performed by incarcerated folks at Rikers. Over the years, the incarcerated were paid pennies, and asked to absorb a lot of this grief in an emotional way. They're the only mourners for bodies that are buried there. So unclaimed dead from the AIDS epidemic, from just living in New York, from crack, from Covid, there're these waves of deaths that happen in any urban space. But in New York, and as a New Yorker in particular, this was my black hole, I feel some kinds of way about New York. These are my folks that are unclaimed.

Narrator: Olujimi made this painting in the summer of 2020, during lockdown.

Kambui Olujimi: There's something really ghostly about it for me in that they're wearing these hazmat suits. It's so clinical, so much of the epidemic was about a loss of touch.

I wanted to include the landscape so that as a viewer, I felt like I was there, that I'm engaged, that I can feel the sort of pits. There were so many graves being dug during the pandemic that there were bulldozers, and they're mass graves in general. So this heavy machinery, it's not just one person, but then people come in and they might shape it or cover it back. But it's real terraforming. So the landscape was important to me. Also, a sense of scale and openness.

Kambui Olujimi, Hart Island Crew, 2020

In Inheritance

Exhibitions

Installation photography

-

Installation view of Inheritance (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, June 28, 2023—February, 2024). From left to right: Kevin Beasley, The Road, 2019; Cameron Rowland, Lynch Law in America, 2021; Cameron Rowland, Life and Property, 2021; Andrea Carlson, Red Exit, 2020; Kambui Olujimi, Hart Island Crew, 2020. Photograph by Ron Amstutz

From the exhibition Inheritance