Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

1940–2025

Introduction

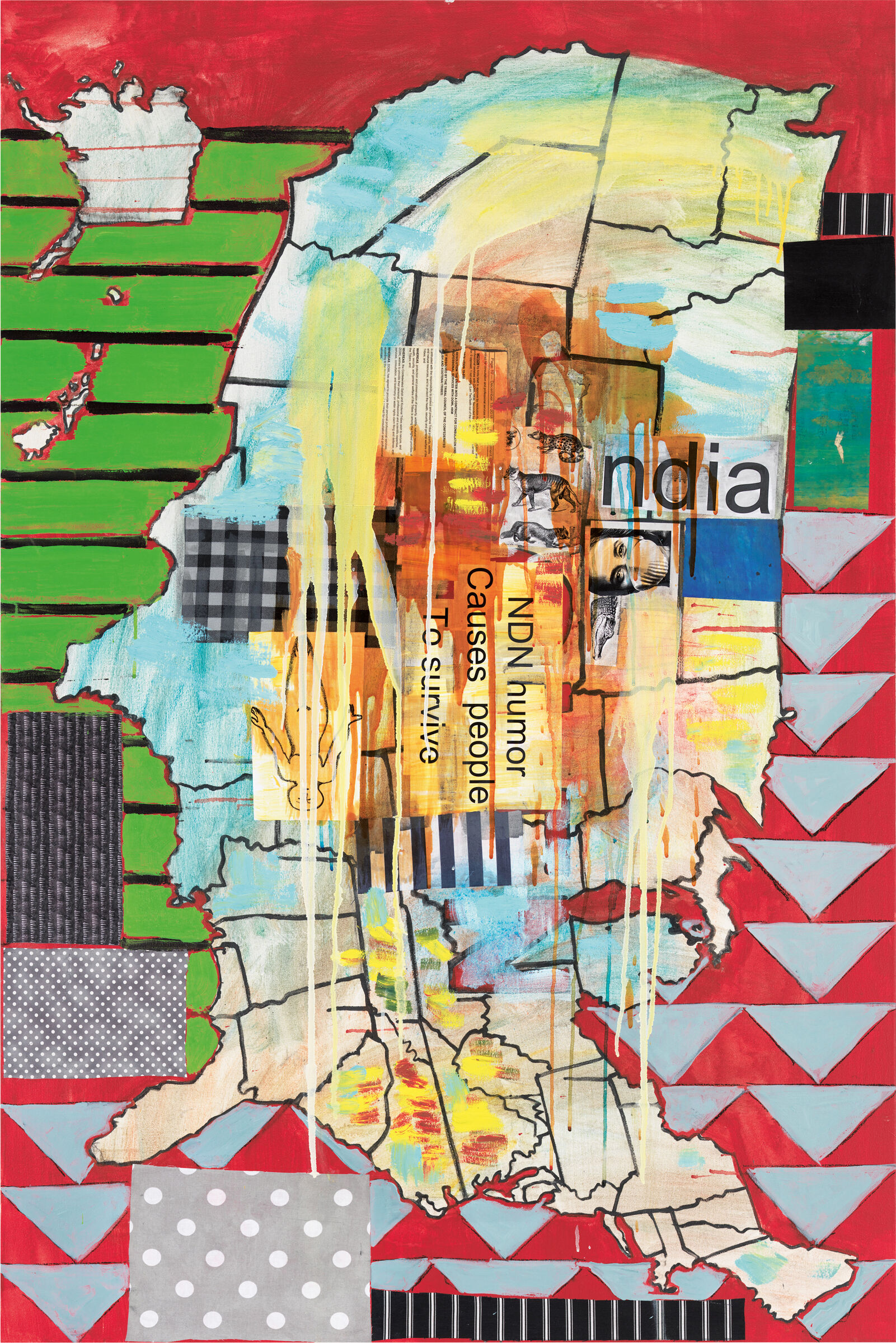

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (January 15, 1940 – January 24, 2025) was a Native American visual artist and curator. She was an enrolled citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and was also of Métis and Shoshone descent. She was an educator, storyteller, art advocate, and political activist. In her five-decades-long career, Smith gained a reputation for her prolific work, being featured in over 50 solo exhibitions and curating more than 30 exhibitions. Her work draws from a Native worldview and comments on American Indian identity, histories of oppression, and environmental issues.

In the mid-1970s, Smith gained prominence as a painter and printmaker, and later advanced her style with collage, drawing, and mixed media. Her works have been widely exhibited and many are in the permanent collections of prominent art museums including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Denver Art Museum, Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, and the Walker Art Center as well as the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the National Museum of Women in the Arts, both in the District of Columbia. Her work has also been collected by New Mexico Museum of Art (Santa Fe) and Albuquerque Museum, both located in a landscape that has continually served as one of her greatest sources of inspiration. In 2020, the National Gallery of Art bought her painting I See Red: Target (1992), which was the first painting on canvas by a Native American artist in the gallery.

Smith supported the Native arts community by organizing exhibitions and project collaborations, and she also participated in national commissions for public works. She lived in Corrales, New Mexico, near the Rio Grande, with her family. Smith was represented by the Garth Greenan Gallery in New York City.

Wikidata identifier

Q4415659

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed February 13, 2026.

Introduction

Smith was known from the 1970s for painting and printmaking, and later collaged works. She was the subject of a retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American art in 2023.

Country of birth

United States

Roles

Artist, designer, lithographer, mixed-media artist, painter, pastelist, sculptor, serigrapher

ULAN identifier

500092544

Names

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, Jaune Smith, Jaune Quick-to-see Smith, Jaune Quick-To-See Smith

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License. Accessed February 13, 2026.