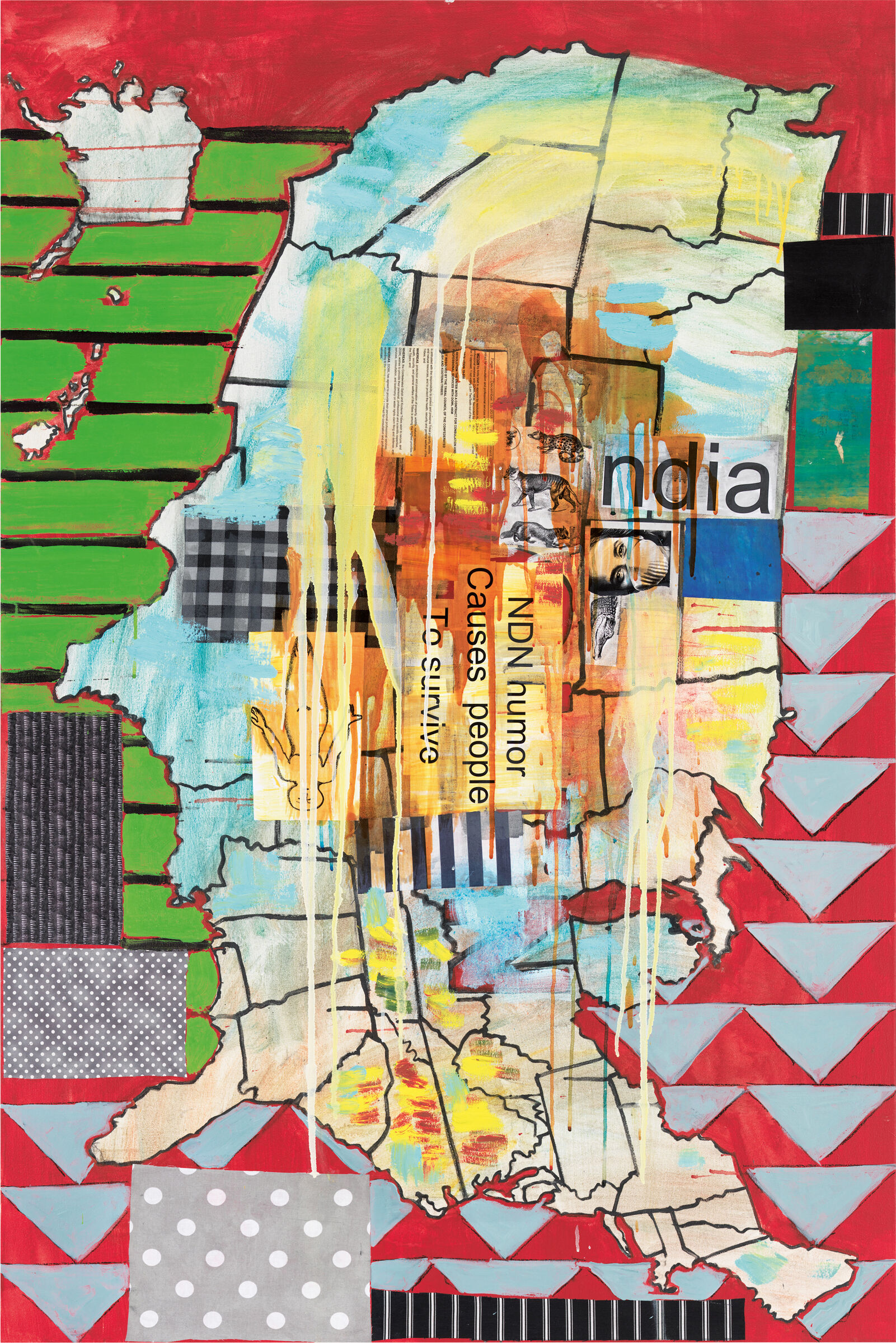

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, War is Heck, 2002. Lithograph, photolithograph and collage, sheet: 58 9/16 × 57 5/8 in. (148.7 × 146.4 cm). Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; gift of Dorothee Peiper-Riegraf and Hinrich Peiper 2006.287. Courtesy the artist and the Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

War is Heck, a lithograph, contains a medley of imagery and sources that reflects the cross-cultural experiences of its maker. Jaune Quick-To-See Smith’s paintings and prints fuse the aesthetic of traditional Native American art with the fractured forms of modern European and American artists such as Pablo Picasso, Paul Klee, and Robert Rauschenberg. Here, for example, an outline of a horse—a frequent subject of Smith’s, and one that alludes to her background—dominates, but images of a soldier, an American flag, and a newspaper headline about war expand the work’s referential scope. Smith’s technique reinforces her theme: the multilayered process of chine-collé functions as an allegory for the convergence of different cultures.

Visual description

War is Heck is a lithograph and photolithograph collage. The dimensions are nearly a square, about 58 inches high by 57 inches wide. The background is predominantly light beige and the most prominent image is a side profile view of a horse facing the left. It takes up most of the canvas, reaching close to the edges. It is drawn with a thick sketchy and painterly black outline. Shading and details are minimal except for straight angular lines across the horse’s body and neck. Behind and surrounding the horse is a “collage of converging cultures”, drawing on imagery from Indigenous, Mexican, and Colonial American visual cultures. A wash of blue drips from the top to bottom of the canvas layering beneath the horse’s body and above several faded details like bison printed postage stamps, a horizontal drawing of a pipe with a long handle, and bingo sheets.

Right below the tip of the horse’s back right hoof is a small image of a Mexican lotería card, El Soldado, depicting a soldier standing up straight holding a gun. The same lotería card is printed larger on the top left of the canvas by the horse’s head. Printed small beneath the horse’s snout is the text “The Stone Age, Up Close and Personal”. To the right is the newspaper headline “WAR IS HECK” printed large in all caps, overlapped by the horse’s chest. On the left edge of the canvas is a wash of red dripping down to the bottom of the canvas. Its streaks overlap a silhouette of cow imagery, which repeats in other parts of the painting, and a small lotería card, La Mano, which depicts a hand, palm facing towards us. The top right of the canvas has a small grid of four American flags directly above the lotería card, El Pajaro, depicting a bird perched on a branch.

The artist has long spoken out against the violence of war, but in 2002, when she made this work, she was responding to the imminent invasion of Iraq by the United States. She said in a later interview: “You know I always think this work is going to be obsolete. And then next year comes and things get worse, or another war starts, so this work stays ever present.”

Not on view

Date

2002

Classification

Prints

Medium

Lithograph, photolithograph and collage

Dimensions

Sheet: 58 9/16 × 57 5/8 in. (148.7 × 146.4 cm)

Accession number

2006.287

Edition

1/10 | 4 TPs, BAT

Publication

Printed and published by P.R.I.N.T. Press

Credit line

Gift of Dorothee Peiper-Riegraf and Hinrich Peiper

Rights and reproductions

Courtesy the artist and the Garth Greenan Gallery, New York

Audio

-

0:00

Verbal Description: War is Heck, 2002

0:00

Narrator: War is Heck is a lithograph and photolithograph collage. The dimensions are nearly a square, about 58 inches high by 57 inches wide. The background is predominantly light beige and the most prominent image is a side profile view of a horse facing the left. It takes up most of the canvas, reaching close to the edges. It is drawn with a thick sketchy and painterly black outline. Shading and details are minimal except for straight angular lines across the horse’s body and neck. Behind and surrounding the horse is a “collage of converging cultures”, drawing on imagery from Indigenous, Mexican, and Colonial American visual cultures. A wash of blue drips from the top to bottom of the canvas layering beneath the horse’s body and above several faded details like bison printed postage stamps, a horizontal drawing of a pipe with a long handle, and bingo sheets.

Right below the tip of the horse’s back right hoof is a small image of a Mexican lotería card, El Soldado, depicting a soldier standing up straight holding a gun. The same lotería card is printed larger on the top left of the canvas by the horse’s head. Printed small beneath the horse’s snout is the text “The Stone Age, Up Close and Personal”. To the right is the newspaper headline “WAR IS HECK” printed large in all caps, overlapped by the horse’s chest. On the left edge of the canvas is a wash of red dripping down to the bottom of the canvas. Its streaks overlap a silhouette of cow imagery, which repeats in other parts of the painting, and a small lotería card, La Mano, which depicts a hand, palm facing towards us. The top right of the canvas has a small grid of four American flags directly above the lotería card, El Pajaro, depicting a bird perched on a branch.

The artist has long spoken out against the violence of war, but in 2002, when she made this work, she was responding to the imminent invasion of Iraq by the United States. She said in a later interview: “You know I always think this work is going to be obsolete. And then next year comes and things get worse, or another war starts, so this work stays ever present.”

Verbal Description: War is Heck, 2002

-

0:00

Verbal Description: Introduction

0:00

Narrator: When you exit the elevators, you will be confronted by two walls offset from the center. To the right is a darker painted wall with the Josh Kline exhibition information, and to the left is a soft white wall with a large painting by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, as well as the introductory information for the exhibition. This retrospective exhibition’s full title is Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map, and the large artwork featured alongside the information is Trade Canoe: Forty Days and Forty Nights, 2015. This piece spans three separate canvases which have all been connected; the two on the left and right are oriented horizontally, and the one in the middle is oriented vertically. The work measures sixty inches tall by one hundred inches long, and through various mediums, depicts a scene of a canoe filled up with many items and creatures, including flying skeletons with feathery wings, a buck head, a snake, a rabbit, a crying eye, and most notably, a tall, dark coyote figure oriented just right of center. This painting will have caution strips on the floor in front of it.

This first gallery space revolves around a large sculpture entitled Indian Madonna Enthroned, 1974, which is situated on a eight inch tall platform in the middle of the space. This sculpture depicts a human figure sitting sideways on a wooden chair: an American flag lies across her lap, a picture frame encases her face, and an ear of corn sits in the place of her heart. In one of her hands is a book titled God Is Red. The cradleboard on her back supports her baby, whose body is made out of sheepskin and whose face is also encased in a picture frame. This sculpture measures 52 inches by 34 inches by 20 inches. On either side of this sculpture against the wall are two works, Ronan Robe #2, 1977 and Ronan Robe #4, 1977. The Ronan Robe works include lodgepoles, or poles of pine, leaning against canvas hangings on the walls of the gallery. A strip of friction tape precedes them, but they are not secured to the wall, so please navigate around the perimeter of the room with care.

The exhibition was designed in collaboration with the artist to prioritize collectivity and a connection to outdoor spaces, informed by the artist’s own Native American ideology and values. With that in mind, the exhibition was designed not as a series of discrete galleries, but as one diffuse space where the placement of works on view are not predetermined by strict chronology or thematic elements, but a mix of both strategies. Open corners, offset walls, and large entryways between galleries encourage a cyclical and cross-pollinated approach to viewing and interacting with the work.

The center of the exhibition is a sort of segmented hallway created between the north and south sides of the whole exhibition space by the offset entrances to the galleries. Each section of wall is accented by a monumental painting, ferrying the visitor toward the wall of windows on the south side of the fifth floor. Throughout this exhibition, visitors are encouraged to reflect on their own position and the connective relationship to nature and the outdoors.

Throughout the galleries, you will find opportunities to commune with other visitors: large openings to each space and custom furniture designed to encourage conversation allow for a variety of ways to enjoy and be present in the galleries.

The first gallery space with Indian Madonna Enthroned is oriented around the earliest works of Smith’s career. The gallery opens at a forty-five degree angle into the larger exhibition space. It is not necessary, but if you would like to follow the narrative curatorial thread, you should proceed to the right after encountering Tongass Trade Canoe and work down the south side of the galleries first.

If this is the route you choose to take, you will find yourself first in the gallery containing some of Smith’s earliest maps and activism. You are invited to sit on the benches situated in the middle of this room. Moving east, the next space is focused on the early environmentalism of Smith’s Chief Seattle series, a slightly smaller gallery space. This opens into the large fourth room, featuring works made around the Columbian quincentenary. The large space has generous communal seating in the middle. The next space is oriented around the themes of imperialism and colonialism, and includes a number of works that the artist made in critique of war. If you continue east, you will find a large wall of windows, a few couches where you are invited to sit and view a cast bronze sculpture of a coyote head tilted Urban Trickster, 2021. If you loop around back toward the northside of the galleries, you’ll find yourself in a room focused on the theme of American capitalism and consumerism. In the center of this gallery, a pinewood lath and synthetic sinew canoe sculpture, titled Trade Canoe: Making Medicine, 2018, hangs suspended from the ceiling. A five inch tall platform sits below it on the ground. Continuing through the rest of the northwest galleries, you will experience two galleries subdivided by a floating wall. These spaces address the importance of Indigenous traditions and the leadership of Native American women. On the west side of the floating wall, a motorized, animatronic sculpture, titled Warrior for the 21st Century, periodically dances, moving up and down from the floor. You can find a full audio description for this piece on our mobile guide. The final gallery in this route returns to the idea of mapping with a focus on depictions of the U.S. map, and also has a view of the first gallery space with the earliest maps that were encountered in the beginning of this path. This vantage articulates the cyclical and overarching ideas that guide this exhibition.

The final gallery with work by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith on this floor is the Kaufman Gallery that can be accessed through the hallway that leads north. In the corridors as you approach the final gallery are drawings on paper, as well as a documentary video and some ephemera related to Smith’s curatorial organizing. There is a bench in this space to make watching the twenty-five minute video more comfortable. The final gallery in Kaufman is centered around the future and the environment.

It is important to note that moving south and looping around to the north is not a prescription for how you should navigate through the space. You are welcome to meander in and around through the offset entryways and exits to each gallery space. It is also important to note that while the primary exhibition is on the fifth and third floors, work by Jaune Quick-to-See Smith is also sprinkled throughout the Museum: including coyote drawings and paintings on the lower level floor with coat check, to the hallways on the sixth and seventh floor, and a coyote sculpture on the outdoor terrace on the eighth floor.

Verbal Description: Introduction

-

0:00

War is Heck, 2002

0:00

Narrator: In War is Heck, Smith used a printmaking technique called chine-collé to collage bits of paper onto the background. Throughout this work, the artist inserts references to war. In the upper left hand corner, you can find a card from the Mexican game of chance, lotería. It reads “El Soldado,” the soldier.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: It’s like the common people going to war, being led to slaughter. Because the dictators or the men in power, you know they always stay safe and the people wind up on the battlefield, or in their villages. And often it's the women and children.

Most of the time in the 2000s I was reacting to the issue of the Iraq War, or, you know, things that were going on in the Middle East, Afghanistan. You know I always think this work is going to be obsolete. “Oh, I'm making this now but, you know, next year this could be ended and we won't be dealing with this.” And then next year comes and things get worse, or another war starts, so this work stays ever present.

War is Heck, 2002

-

0:00

Introduction

0:00

Narrator: Welcome to Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map. Together we’ll explore five decades of Smith’s career, looking at paintings, prints, drawings and sculpture.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Most people will never have heard of me. And that’s not off-putting.

Narrator: Jaune Quick-to-See Smith.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: It’s that maybe it will start to crack this whole issue of Native Americans being invisible. Being Indigenous in making art means that you’re looking at the world through lenses that are curved or changed by your upbringing and by your worldview.

Narrator: For Smith, who is a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Nation, that worldview first began to form in the Pacific Northwest and western Montana. Today, Smith lives and works in New Mexico. Throughout her life and work, she has underscored the importance of the land and of Indigenous communities. As we move through the exhibition, we’ll look at the ways in which Smith addresses the traumas of Native American people with rigor, inventiveness, and critical humor.

You can use this guide to explore the works in any order you wish. As you go, you’ll be hearing not only from Smith but from writers and other artists including Neil Ambrose-Smith, Andrea Carlson, Jeffrey Gibson, G. Peter Jemison, Josie Lopez, and Marie Watt.

Introduction

Exhibitions

Installation photography

-

Installation view of Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, April 19-August 13, 2023). From left to right: War is Heck, 2002; The King of the Mountain, 2005; Imperialism, 2011. Photograph by Ron Amstutz

From the exhibition Jaune Quick-to-See Smith:

Memory Map