American Artist: So the earliest computer interfaces always had blackness as a basis of what could be done on a computer.

My name is American Artist. That is not the name I was born with. I changed my name in 2013. I grew up in Southern California, but I moved to New York around the time that I changed my name and I've been living here ever since. I'm an artist and an educator.

This work is a functional computer that is made out of dirt. It has this material of asphalt that's been poured onto it and it's dripping and sticky with this black material. And it's on this standard desk. What you see on the monitor of the computer is white text on a black interface.

The shape of the computer is modeled after the Apple II, which was the last commercial personal computer that used this all black interface. So the earliest computer interfaces always had blackness as a basis of what could be done on a computer. I wanted to make a computer that was really rooted in this moment where blackness served as the basis of what could be done in virtual space.

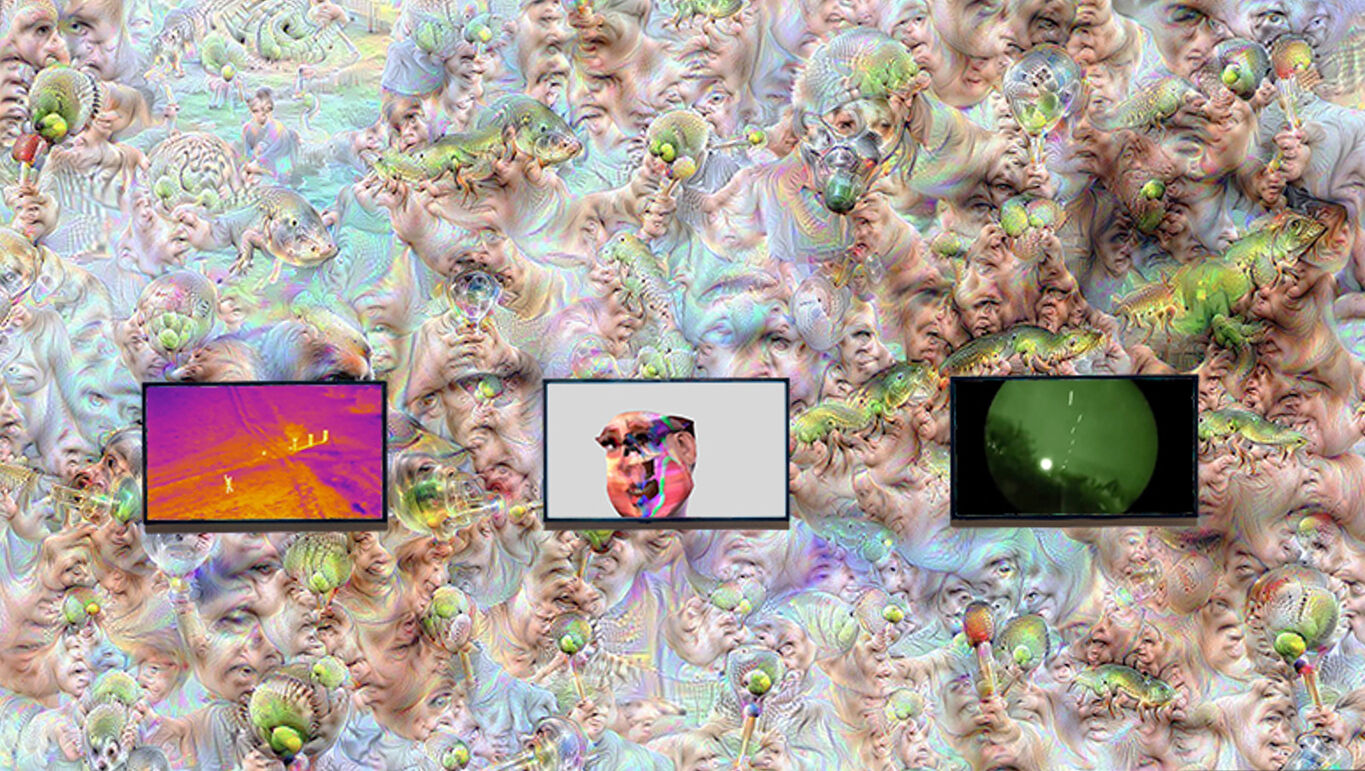

This work is called Mother of All Demos. The name is based off of an event that's pretty well known in the computer science field. This moment in 1969 when Doug Engelbart gave a first demonstration of this new computer interface that he had created alongside the use of a mouse and being able to click around.

Doug Engelbart worked for Stanford Research Institute and he led a lot of innovations around computer technology and interfacing and how they were networked. He pioneered a lot of ideas that were central to the development of Silicon Valley.

And in that moment across the industry, computers began to use this white background as the backdrop for a computer interface. Prior to that, all computer interfaces just used text based languages and you would just type code into a computer screen. When interfaces were text based, they always had this black background on them.

And so whiteness pushed blackness aside as the original background of the interface to bring in this new era of computation. And in that moment it was said, blackness on the computer, it's bad for reading, it's not good for your eyes. And yet nowadays, we see a lot of that formal language of the black aesthetic coming back into computation.

I was thinking about the beginnings of the computer interface and ways in which anti-Black racism had been present in the decisions around what an interface would look like. This piece is part of the series Black Gooey Universe. There's hand prints next to where the keyboard of the computer would be. It appears that someone has just used this computer and they've touched the sticky surface and gotten their hands covered in this black material.

This word gooey is a way of saying this acronym GUI, which means graphical user interface. And that is a type of interface where you have windows and folders, and a mouse and a cursor, and you can click around. And so the Black Gooey was really about thinking about what a computation rooted in Blackness could look like and what kind of material manifestations it might have.

It was a return to that moment, but also wanting to rethink all of the values that we associate with computing that things need to be fast or pristine or mimic an office space—wanting to question what that idea of use even means and for who. For who are these things productive? Is productivity the only desired outcome of a device like this?

I do imagine someone having just used this computer, not someone that actually exists. It's a speculative person for whom this looks like a very inviting computer. This is a type of computer that represents their values and understanding of computation. And what I was really trying to do was make something that for anyone entering the gallery this would look uninviting.

I wanted to make something that felt dirty, sticky, things that you wouldn't necessarily want to touch, but then to show that someone actually is using this thing. And that was really about showing how much different computer technology could be if someone else had been in the room deciding what these different visual and formal design strategies would be.

And so if, let's say, a group of straight cis white men in the 1960s designed this office space device to mimic what they saw as a average way that someone might engage with information and visual information, what does it mean for that to then inform the way that everyone will engage with it from that point forward in perpetuity?

This work very much does feel like a thought experiment because it's pulling together these different histories and trying to flip them on their head and get us to really question how we even relate to computer technology. So much of what I'm trying to do in art doesn't really feel like how most people think about art, but it feels like it's trying to do a lot more in terms of shifting culture, raising consciousness about different political issues, and trying to use these formal and visual strategies as much as possible to really embed all of these deep thoughts into a material object.

Mother of All Demos is providing an alternative that is not necessarily attempting to resolve an issue. It's just provoking. It's saying, what if this computer is almost not useful? What if use isn't the main goal or deliverable of this object? But rather, it's merely intent on expressing different ways to exist or communicate that fall outside of everything we understand a computer to be able to do.