Refigured

Mar 3–July 3, 2023

Refigured

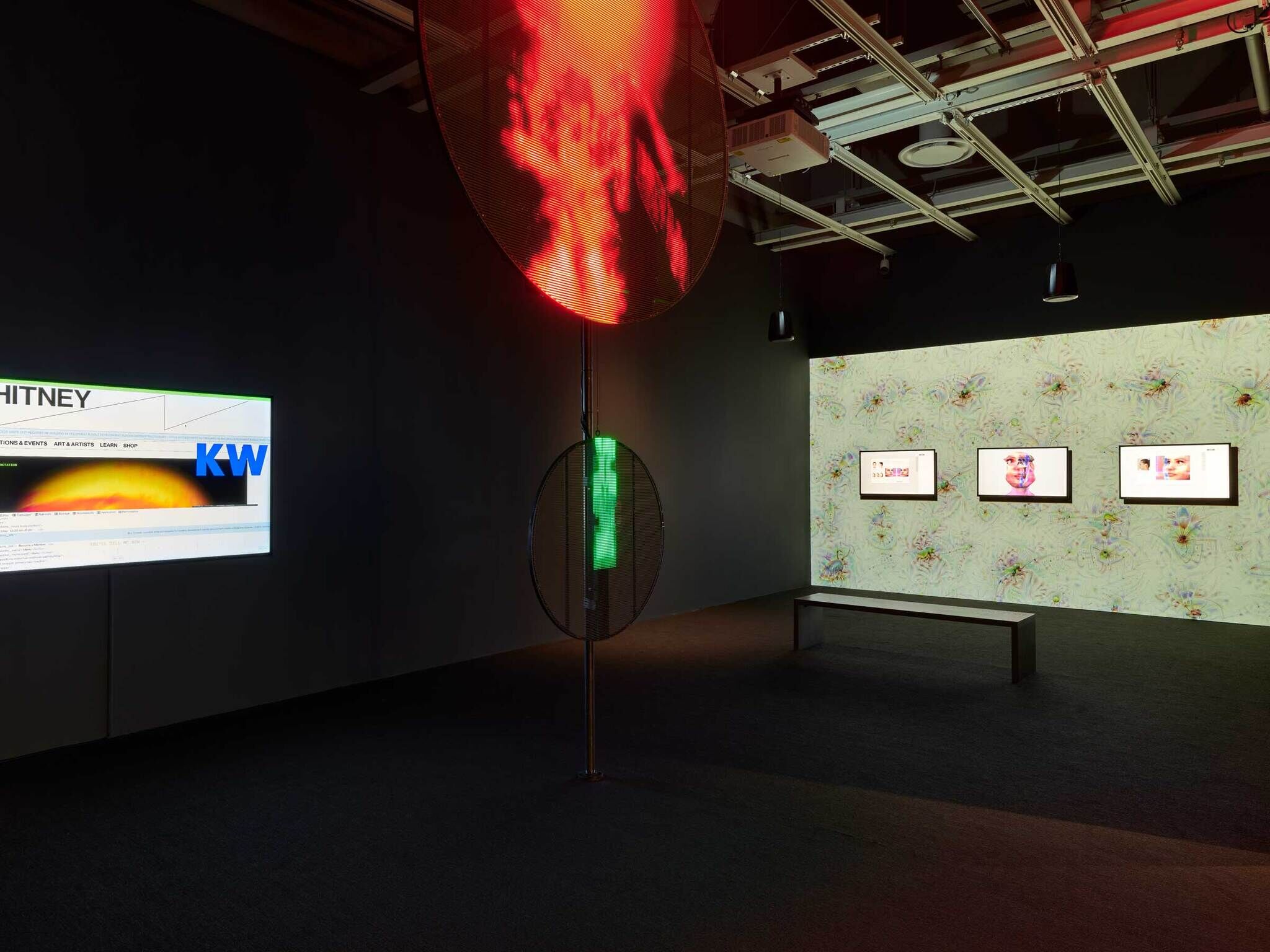

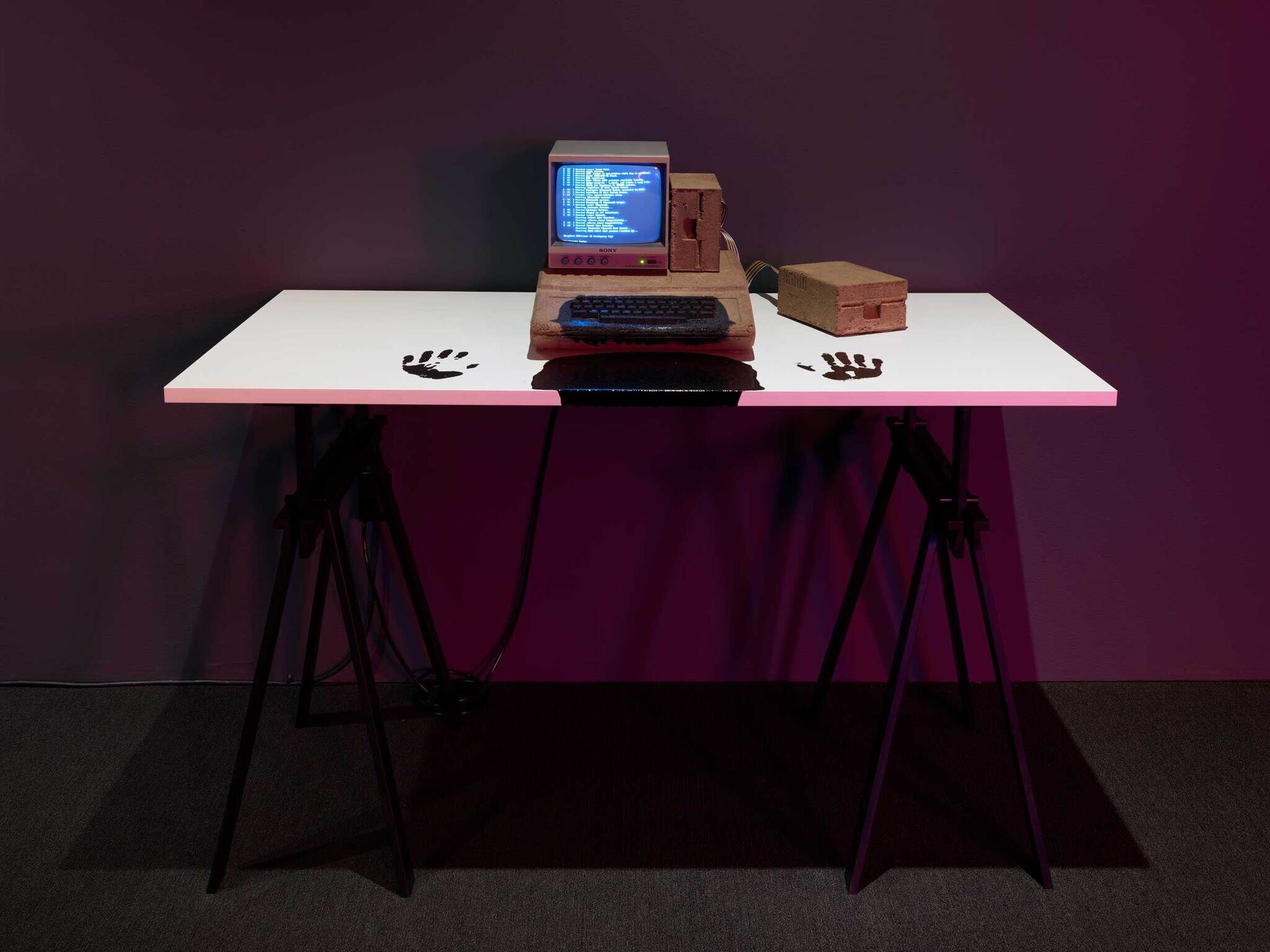

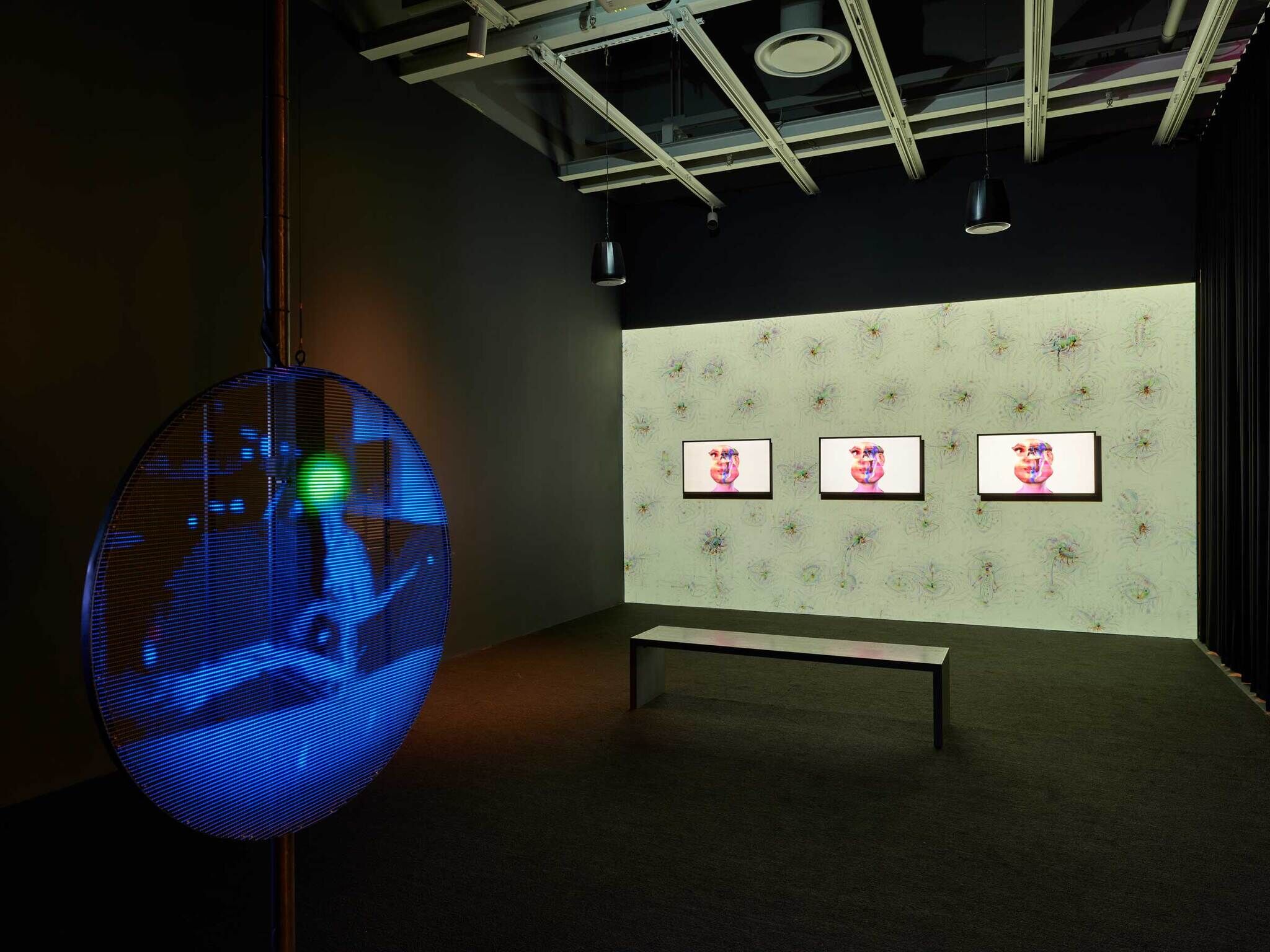

Drawn from the Whitney’s collection and including video, animation, sculpture, and augmented reality, the works in Refigured reflect on interactions between digital and physical materiality. Sculptures are simultaneously physical and virtual, while video and animation extend beyond screens and into the gallery. The exhibition brings together a group of artists—Morehshin Allahyari, American Artist, Zach Blas and Jemima Wyman, Auriea Harvey, and Rachel Rossin—who engage with the concept of “refiguring,” appropriating material forms and bodies to re-create and reinvent them. Refiguring becomes a process of imagining alternative worlds as a means for constructing identity.

The five installations on view in this exhibition respond to the various forces that form identity, such as new modes of self-representation (via avatars) and even structures of oppression, from technological systems to colonialism. Some works explore how identity is embedded in the development of computer interfaces and artificial intelligence. Others address the refiguring of identity in both online environments and ancient cultural myths. Together, the works highlight the porous boundaries between today’s material and virtual realms, and the ways in which their interplay shapes our idea of selfhood.

This exhibition is organized by Christiane Paul, Curator of Digital Art at the Whitney Museum of American Art with David Lisbon, curatorial assistant.

Generous support for Refigured is provided by the John R. Eckel, Jr. Foundation.

artport: Internet art at the Whitney

artport is the Whitney Museum's portal to Internet art and an online gallery space for commissions of net art and new media art. Originally launched in 2001, artport provides access to original artworks commissioned specifically for artport by the Whitney. Many of the artworks in Refigured are artport commissions.

In the News

“The depth and complexity of each work…makes it a show in which one can linger, each of these five works proving absorbing and thought-provoking in its own way.” —The Guardian

“…plunges viewers into the digital now.” —The Wall Street Journal

“Sometimes refiguring means working anew with histories recent and long past; other times it means giving physical form to the digital.” —Artnet

“…probe into new modes of self-representation, while examining a number of structures that shape them…” —Hypebeast