Minisode: Virginia Overton on Ruth Asawa

Dec 19, 2023

0:00

Minisode: Virginia Overton on Ruth Asawa

0:00

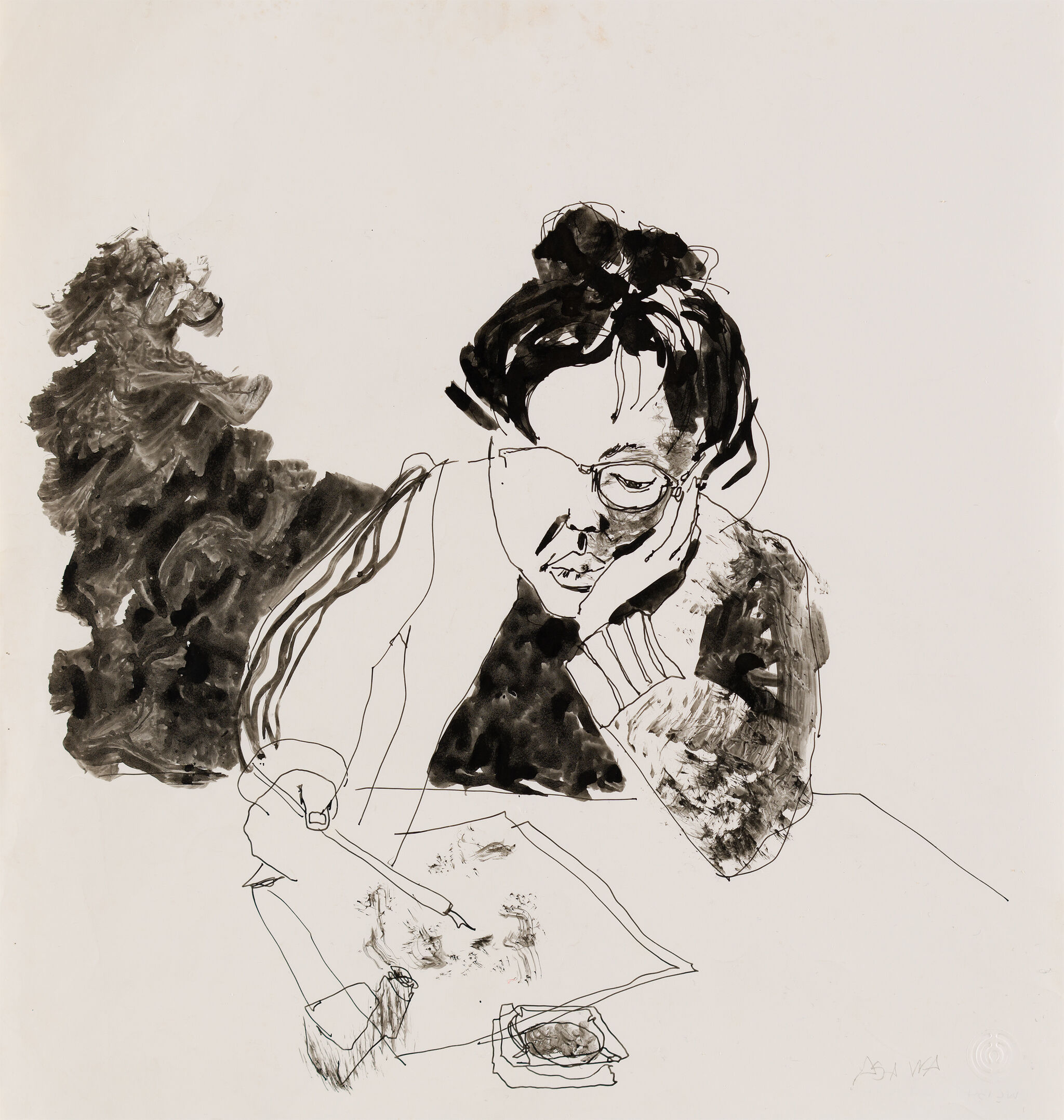

Narrator: Welcome to Artists Among Us Minisodes from the Whitney Museum of American Art. On the occasion of the exhibition Ruth Asawa Through Line, we sat down with artist Virginia Overton to hear about what she finds so interesting about Ruth Asawa’s work. Asawa is widely known for her wire sculptures but, in this exhibition, it’s her dreamy works on paper that take the spotlight. Overton speaks about three pieces. One is a print made from the body of a fish. The other two are ink drawings, one showing the cross-section of a redwood tree, and the other of the curly leaves of endive lettuce. Here is Overton on Asawa.

Virginia Overton: Gosh, I'm trying to remember when I first saw her work. It feels like such a part of art for me that I don't really remember when I first saw it in-person for sure. Of course, I'd seen it in books and publications prior to seeing it in-person. But part of what interests me is her dedication to process—a continued investigation, a very rigorous practice. Seemed like she was always doing something, making art, gardening, taking care of family, cooking. But it was always an integrated process for her, art making was part of life making.

So the fish print in the exhibition really intrigued me because twenty or thirty years ago, I made a fish print and it felt like there was a similar energy in her print and mine. Hers is obviously a print from a fresh whole fish that hasn't been scaled or fileted. Mine was actually a fish skeleton with the head still on, so it had been fileted. But in each case, it's like there's this immediacy of needing to get to print and there's no time to waste. And so the paper you see in her fish print is clearly rapidly gathered and taken to make this print rather than a very slow, steadied process. There's an urgency to it. And the fish print that I made was on a brown paper sack. It's all I had, and black porch paint. And so it was the combination of those two things that allowed me to get the print of this object— this fish—before it disintegrated back into the earth.

For Asawa I would imagine the pattern of the scales would be something she'd be very interested in. For me, it was like that too. But I was seeing the structure or the armature on which a fish is made essentially. So it's like a sculpture in that sense. There's an internal armature, and then these components that create the whole thing.

Being a sculptor, I'm looking around at the world and everything is potential material. Human-made materials, organic materials, new things, old things, detritus. I mean, everything is a potential material or a potential way to investigate an idea sculpturally. So maybe it's a temporary material that's going to disintegrate, but it still has potential for being a sculpture. I think with Asawa's work, she captures these things at a certain a moment in time.

So in this drawing, one of the things that struck me initially was whether it was a drawing of an actual slice of a tree or a drawing of the idea of a tree and what a tree is. And so looking at it, I could see it both ways. But it's interesting if it is the drawing of the idea of tree, it does such a succinct job of capturing that.

Asawa starts with a really small inner circle, and then she copies it over and over and over again until they fill the page so much that there's no more space to draw circles. And it was like she would draw until she couldn't draw anymore, until the end of the page ran out. I work with wood so much and seeing this drawing really evoked something emotional in me almost. I'm very familiar with and connected to all types of wood, and I remember seeing my first redwood in California when I was in my twenties. It was such a massive, massive tree, and it was just shocking to see something that was so old and still standing and still thriving.

So when I saw this drawing of Asawa's, the fact that it's 356 rings suggests quite an old tree, and then this convergence of her hand replicating that feeling of such age in a tree really captivated me. If you're capturing those rings at that moment, that's one snapshot. Or with a head of endive, it looks like that for a moment before it wilts. If you've picked it, and then it's sitting there, it has a certain look, but after some time, it will change and decay. So there's an urgency in her work. I mean, there's a rhythm that exists in her drawings and sculptures that I'm really attracted to as well. And I think that those mark living time in a way. So the drawings definitely feel like they record time. They definitely record her hand, pencil to paper, and I find that really intriguing.

That's the compulsion of being an artist is that you're always investigating, whether you're literally making art, physically drawing, or making a sculpture, or if you're just walking around in the world. All of these things become a sort of visual inventory that you can then draw from when you're making work.

In doing more research about her, I got really interested her, so I watched videos and looked at just everything I could find. There was one scene in one of the films that I watched where Buckminster Fuller comes over and they walk up to the front doors of her house and then you walk through her house and she's surrounded by her world, which is her family, her garden, her community, her art. I mean, just, it's all woven together like her sculptures are woven together.

Narrator: Artists Among Us Minisodes are produced at the Whitney Museum of American Art by Anne Byrd, Nora Gomez-Strauss, Sascha Peterfreund, Emma Quaytman, and Emily Stoller-Patterson.

"There's an urgency in her work. There's a rhythm that exists in her drawings and sculptures that I'm really attracted to as well." On the occasion of Ruth Asawa Through Line we chatted with Virginia Overton about what she finds so inspiring about Asawa's work. She speaks about two pieces: a print made from the body of a fish, and an ink drawing showing the cross-section of a redwood tree.