Boldness Knew No Limits: Women and the Emergence of American Abstraction

To be a woman abstract artist in the United States in the 1930s and 1940s was a radical endeavor. Men dominated the artistic profession—a dynamic reinforced by the era’s prescribed social norms—and realism was the prevailing style. American abstractionists were vastly outnumbered, maligned by critics, and largely ignored by museums and galleries. Faced with compound layers of bias, a significant number of women artists nevertheless embraced, and championed, abstraction. They understood themselves as artistic revolutionaries (along with their male counterparts) striving to create a visual language that reflected the advances of the twentieth century, and their efforts propelled the formal, technical, and conceptual evolution of abstract art in this country. With most conventional avenues closed to them, they forged a network of overlapping communities, organizations, and creative spaces to support one another, exchange ideas, and exhibit their work. Women were integral figures in these circles, often taking on leadership roles. They wrote and lectured about modern art, organized exhibitions, and advanced methods of making, particularly in print media. This essay seeks to illuminate what drove women to make abstract art during this period—and why so many of them remain overlooked today in spite of their critical contributions. It complements the Whitney Museum’s exhibition Labyrinth of Forms: Women and Abstraction, 1930–1950, which gathers an array of drawings and prints that exemplifies their aesthetic experimentation and innovation.

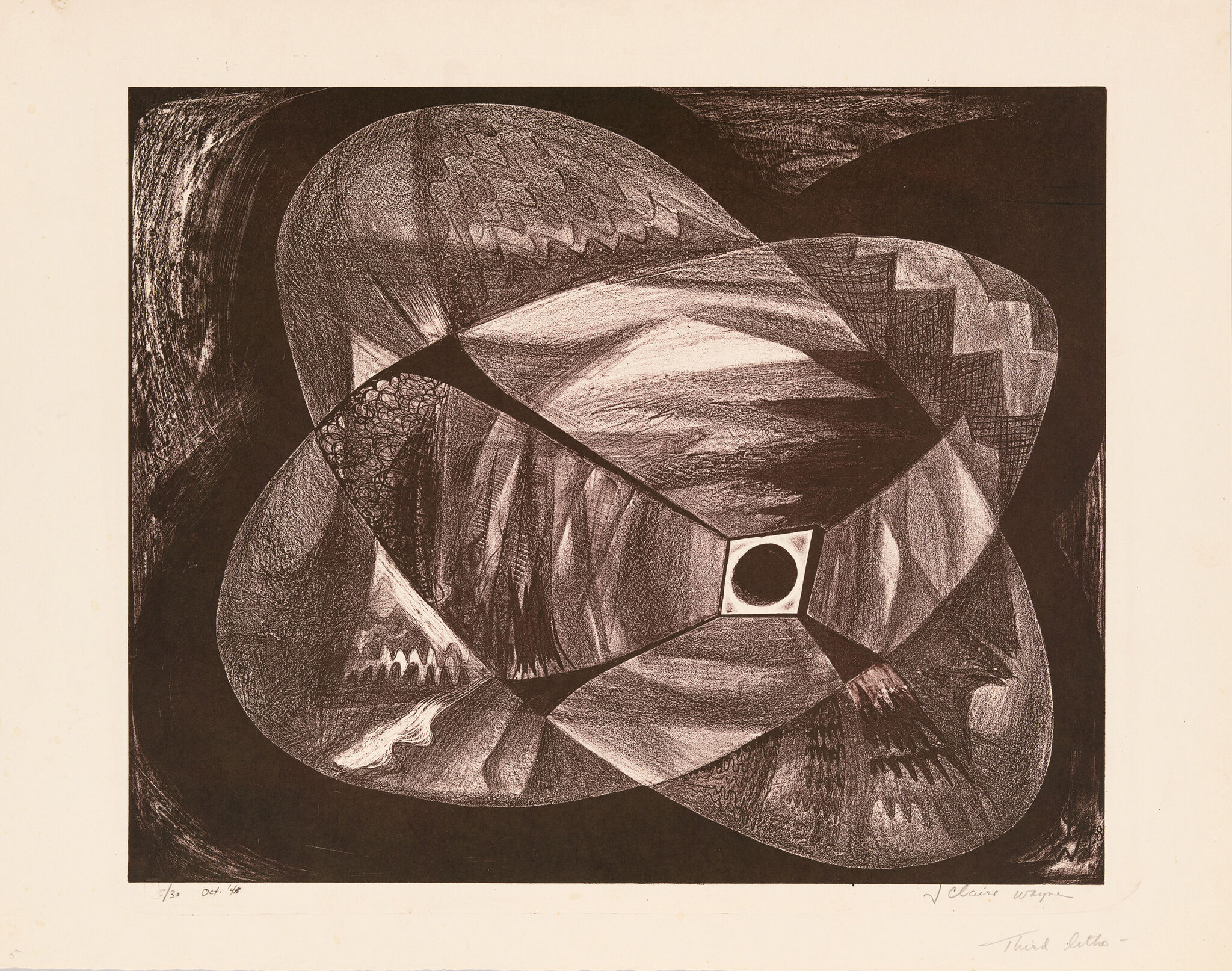

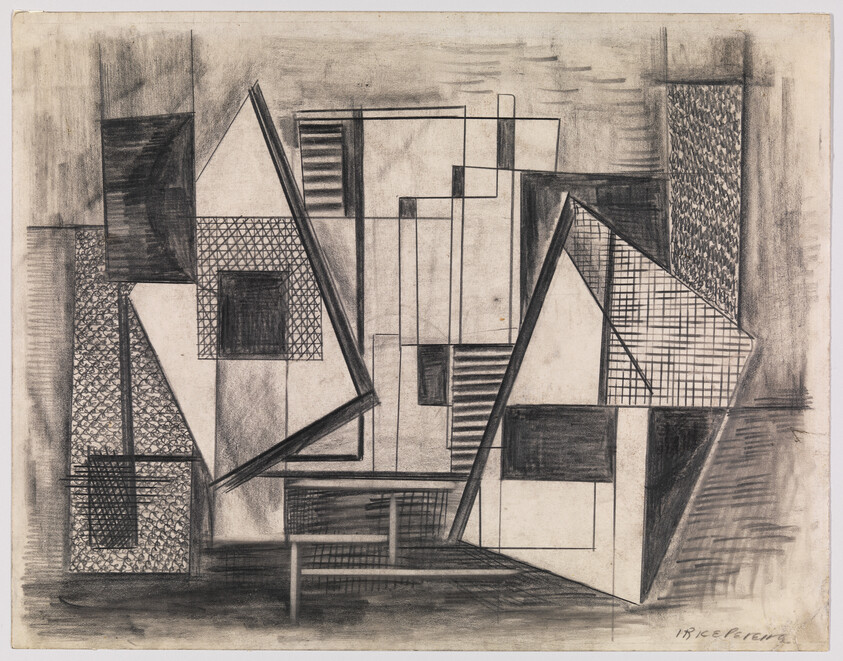

Women artists of this period contended with sexism regularly. Some—including a few whose work is on view in Labyrinth of Forms—attempted to circumvent such bias by exhibiting under names that disguised their gender identity: Irene Rice Pereira typically showed as I. Rice Pereira, and Dorr Bothwell legally changed her name from Doris because she believed that her obviously feminine name prevented her inclusion in exhibitions. Their concerns were well founded. Professionals in the field often expressed surprise when women created what they regarded as successful works of art. Artist and teacher Hans Hofmann described a drawing by his student Lee Krasner as “so good that you would not know it was done by a woman,” and in reviewing the work of Louise Nevelson, a critic declared, “We learned that the artist was a woman in time to check our enthusiasm.”Krasner recounted this incident on numerous occasions, but see for instance Cindy Nemser, “Lee Krasner,” in Art Talk: Conversations with 15 Women Artists, 2nd ed. (New York: Icon Editions, 1995), 85; see review of Louise Nevelson exhibition, Cue Magazine, October 4, 1941, quoted in Helen Langa, “Introduction: Challenges, Tensions, Accomplishments,” in American Women Artists, 1935–1970: Gender, Culture, and Politics, ed. Langa and Paula Wisotzki (London and New York: Routledge, 2016), 8.Women also grappled with powerfully gendered dynamics at home, where many confronted the tension between their creative pursuits and expected domestic duties. Alice Trumbull Mason ceased her artistic practice altogether from 1930 to 1935 in order to focus on raising her children—a decision she lamented. As she wrote to her sister Margaret Jennings in 1934: “Maybe you think intellectual life is not the real thing—but dammit—just caring for babies isn’t either. I am chafing to get back to painting & of course it’s at least a couple of years away. . . . The babies are adorable and terribly interesting. I’m not saying anything against them, but I don’t want to—I can’t be just absorbed in them—even tho[ugh] they won’t be babies for very long.”See Marilyn R. Brown, “Life and Art,” in Alice Trumbull Mason: Pioneer of American Abstraction, ed. Elisa Wouk Almino (New York: Rizzoli Electa, 2020), 18.June Wayne similarly spoke of the difficulty of balancing her marriage and artmaking at the outset of her career.June Wayne said: “I found that whatever prominence I might accomplish as an artist must immediately be paid for in pain in the household. George [Wayne’s husband] couldn't tolerate for one reason or another the sense of my separate existence. . . . I was still trying somehow to accommodate to what was fundamentally impossible. . . . So (to me) my work, you see, was secret, private. Its existence was a heavy burden, of guilt; I had to pay for it with a ‘program’ in the household. And this stretched my capability for doing things well because I would do what I did during the day running the house or whatever in order to feel righteous about buying my own time at night. So it was a bad scene.” See Paul Cummings, oral history interview with June Wayne, August 4–6, 1970, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.Women who married fellow artists were not immune from such pressures. Many chose, or had to assume, a secondary status to their husbands. Rosalind Bengelsdorf gave up artmaking for teaching and writing after she married Byron Browne in 1940; Ray Kaiser’s art was largely forgotten and her contributions to the Eames Office disregarded in the shadow of her husband, Charles; and Krasner was infamously relegated to the role of “Mrs. Jackson Pollock.”Nemser, “Lee Krasner,” 94. Krasner referred to herself in this way in other interviews as well. Many authors have written about Krasner’s role as Pollock’s wife and this gendered dynamic, but see especially Anne M. Wagner, “Lee Krasner as L.K.,” Representations 25 (Winter 1989): 42–57.Yet abstraction granted women aesthetic liberty and mitigated some aspects of this ever-present sexism. Because it largely eliminated identifiable subject matter, abstract art was difficult to classify as obviously feminine or masculine. It also offered a reprieve from the chauvinistic nationalism that characterized much realist work of the period. And as a new approach to artmaking that broke defiantly with the past, abstraction offered opportunities free from what Perle Fine termed the “oppressive particularities” of realism and its potential for gendered readings.Kathleen L. Housley, Tranquil Power: The Art and Life of Perle Fine (New York: Midmarch Arts Press, 2005), 77.

A small number of American artists had begun to work abstractly in the 1910s, but most abandoned these endeavors in the 1920s in favor of more representational modes. By the end of that decade, though, a new generation began to be inspired by abstraction. Some encountered it in educational settings, including in New York the Grand Central School of Art, where Arshile Gorky taught from 1926 to 1931; and the Art Students League, where Vaclav Vytlacil, Jan Matulka, and Hans Hofmann all joined the faculty between 1928 and 1932. Hofmann, who had operated a successful art school in Munich before immigrating to the United States, also taught in California and Massachusetts before opening his own schools in New York in 1934 and Provincetown in 1935. Each teacher had a profound effect. Mason credited Gorky with having “really opened my eyes to abstract painting”; Dorothy Dehner described Matulka as a “very avant-garde figure” who gave his students “as broad a view as possible of the entire spectrum of art” and “had no qualms whatever about accepting a woman painter”; while Fine cited Hofmann as “an opening wedge” for her artistic aims.Brown, “Life and Art,” 17; Dorothy Dehner, “Memories of Jan Matulka,” in Jan Matulka, 1890–1972 (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1980), 78, 80; Housley, Tranquil Power, 33.The modernist influence of these teachers can be seen in works such as Krasner’s Still Life of 1938 (featured prominently in Labyrinth of Forms), a significant departure from the classical mode in which she had worked prior to Hofmann’s instruction. It reveals his emphasis on the importance of negative space, even as the work is far more radical than that which Hofmann was creating at the time.

Some American artists had more direct exposure to abstraction when they traveled abroad—especially to Paris—to formally study, interact with the avant-garde, and see exhibitions of European abstract art. Bothwell, for instance, saw Surrealist work in Paris for the first time in 1930 on what she described as “a day that my head was really turned around.”Dorr Bothwell, Dorr Bothwell: Straws in the Wind; An Artist’s Life as told to Bruce Levene (Mendocino, CA: Pacific Transcriptions, 2013). See also "The Archive of the Mendocino Heritage Artists," courtesy Bruce Levene.Crucially, though, by that time international travel was no longer required for viewing modern art. Katherine Dreier in 1920 had joined with Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray to form the Société Anonyme, which she described as “an international organization for the promotion of the study of the experimental in art.”Katherine S. Dreier, introduction to Catalogue of an International Exhibition of Modern Art Assembled by the Société Anonyme (Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum Press, 1926), n.p.Dreier, who was also a practicing artist, assumed full leadership of the group within a year of its founding. In addition to collecting modern art, delivering lectures, and authoring texts, she organized exhibitions, including a broad survey at the Brooklyn Museum in 1926, and in 1930 and 1931 shows at the Rand School of Social Science and the New School for Social Research, respectively. Both of the latter venues were located in Greenwich Village, home to many burgeoning abstractionists and to the Gallery of Living Art at New York University. Founded in 1927 by A. E. Gallatin, the space quickly became essential to artists. Rosalind Bengelsdorf remembered: “We went there all the time. . . . it was terribly important to us,” particularly since “there was so little going on at that time.”Susan Carol Larsen, “An Interview with Mrs. Rosalind Bengelsdorf Browne,” in “The American Abstract Artists Group: A History and Evaluation of Its Impact upon American Art” (PhD diss., Northwestern University, 1974), 541.Two years later, the Museum of Modern Art opened, providing even greater access to European modernism and showcasing a variety of artistic approaches.

American artists thus were exposed to decades’ worth of European modernism nearly simultaneously through art classes and exhibitions. The Société Anonyme’s Brooklyn Museum exhibition, for instance, included a wide range of artistic styles by more than one hundred artists from over twenty countries in a presentation that was not organized by formal art movements or nationalities. A similarly broad approach characterized academic environments at the time. Sue Fuller described the multifarious drawings produced in Hans Hofmann’s class: “Somebody was just beginning to draw the figure; someone else was starting cubism, another student, abstraction, still another minimal. I’d say the whole range of what could happen on a piece of paper took place there.”Rosalind [Bengelsdorf] Browne, “Sue Fuller: Threading Transparency,” Art International 16, no. 1 (January 20, 1972): 38.Such diversity of styles and conceptual underpinnings allowed Americans to interpret and borrow liberally from European examples in the 1930s and 1940s, and abstraction soon acquired an expansive definition in the United States. It encompassed myriad styles and ideas, from the geometric to the biomorphic to the expressionistic, and from that inspired by scientific advancements to that which was spiritually inflected—yet all conveyed a belief in abstraction as the best means of expressing the technological progress and mood of the new age.

American abstractionists still had few opportunities to exhibit in the 1930s, however. The aforementioned recently opened museums were dedicated primarily to European modernism. The Whitney Museum, which was founded in 1930 and opened to the public in 1931, was committed to American art but mostly exhibited and acquired work produced in a realist vein (indeed, the majority of the works in Labyrinth of Forms would not enter the collection until 1977 or later). Similarly, the few galleries that existed in the 1930s rarely showed American abstract art, convinced that it would not sell. Critics in the United States at the time also were highly dismissive, if not antagonistic, toward abstraction, particularly work made by Americans. While frustrated by the combined dearth of attention and outright hostility, in retrospect a number of artists understood the advantage of this lack of recognition and competition: a heady freedom to experiment. As June Wayne explained, “I, like the other artists, had ideas, not collectors. . . . Undistracted by the possibility of success, all attention was on the work and boldness knew no limits. To show my newest painting to another artist was like showing a griffin I had caught while hunting. There were no critics weighing it, no curators measuring and stuffing it. There were no other griffins to compare it to. Isolation made the griffin possible.”June Wayne, “Avant-Garde Mindset in the Artist’s Studio,” Women Artists News 11, no. 2 (Spring 1986): 27.

Abstract artists nevertheless recognized the pressing need to exhibit their work. Many had formed friendships with like-minded creators through art schools; others met through the Artists Union and the Works Progress Administration/Federal Art Project. The Project not only facilitated social networks but also enabled artists to fully recognize their own professional status. For women participants, who notably received the same pay as men, the Project delivered a double shot of esteem. In November 1936, these groups coalesced into the American Abstract Artists (AAA). As described by Rosalind Bengelsdorf, “The networks meshed and all roads led to the formation of the AAA.”Rosalind Bengelsdorf Browne, “The American Abstract Artists and the WPA Federal Art Project,” in The New Deal Art Projects: An Anthology of Memoirs, ed. Francis V. O’Connor (Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1972), 229.Operating with “a liberal interpretation upon the word ‘abstract,’” the cooperative saw strength in numbers and sought to unite American abstractionists working in different styles with the aims of exhibiting their work, promoting discussion, and increasing public awareness and acceptance.American Abstract Artists, general prospectus (1937), n.p.Within the group, women were treated as equals; they served as officers, participated on committees, wrote for publications, and organized programs.The female founding members of the AAA were Rosalind Bengelsdorf, Mercedes Carles, Anna Cohen, Gertrude Greene, Ray Kaiser, Marie Kennedy, Agnes Lyall, Alice Trumbull Mason, and Esphyr Slobodkina. Many other women participated in the group in subsequent years, including five featured in Labyrinth of Forms: Perle Fine, Lee Krasner, Louise Nevelson, Irene Rice Pereira, and Charmion von Wiegand. Among other significant organizational efforts, Mason, Slobodkina, and von Wiegand each served as president at various points.

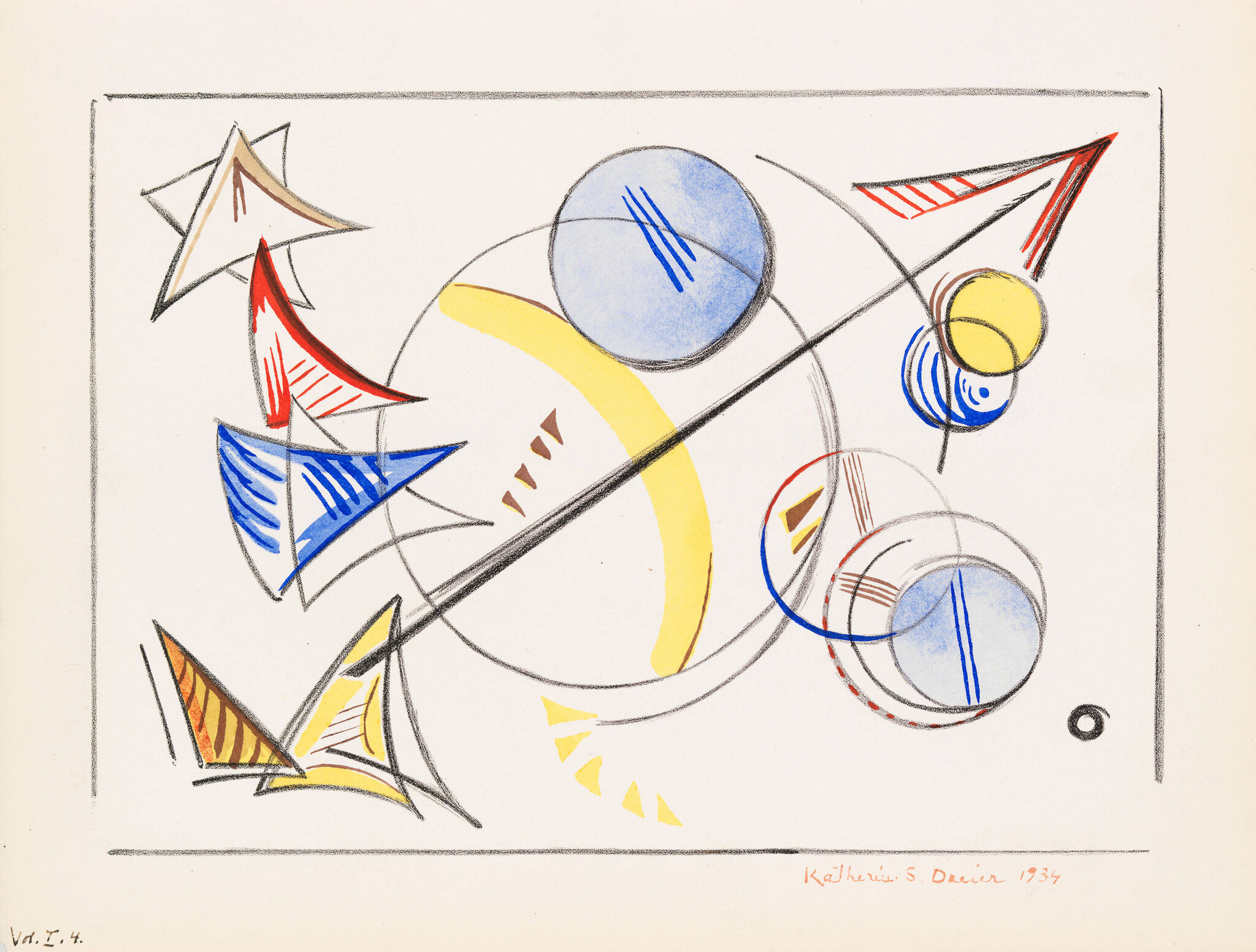

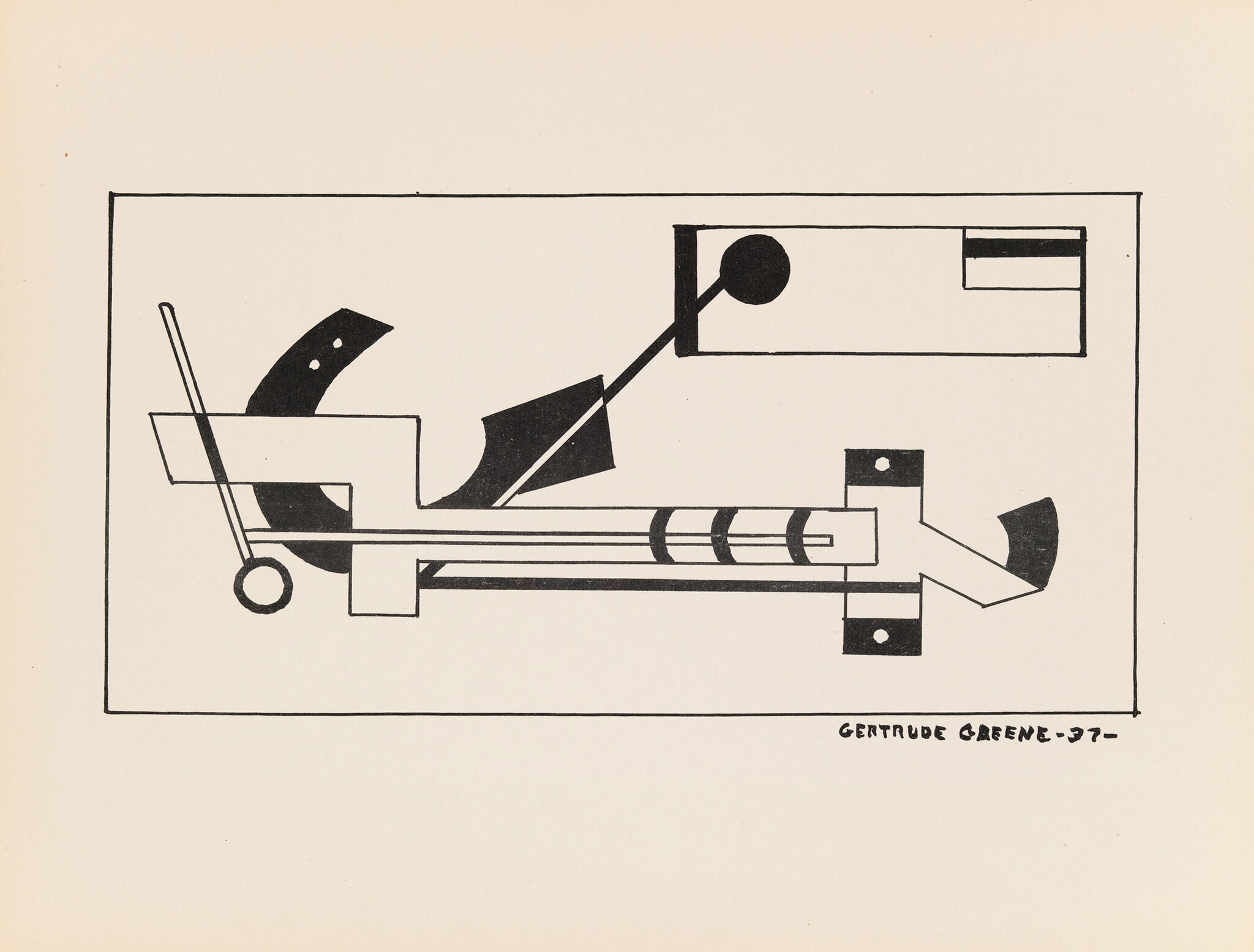

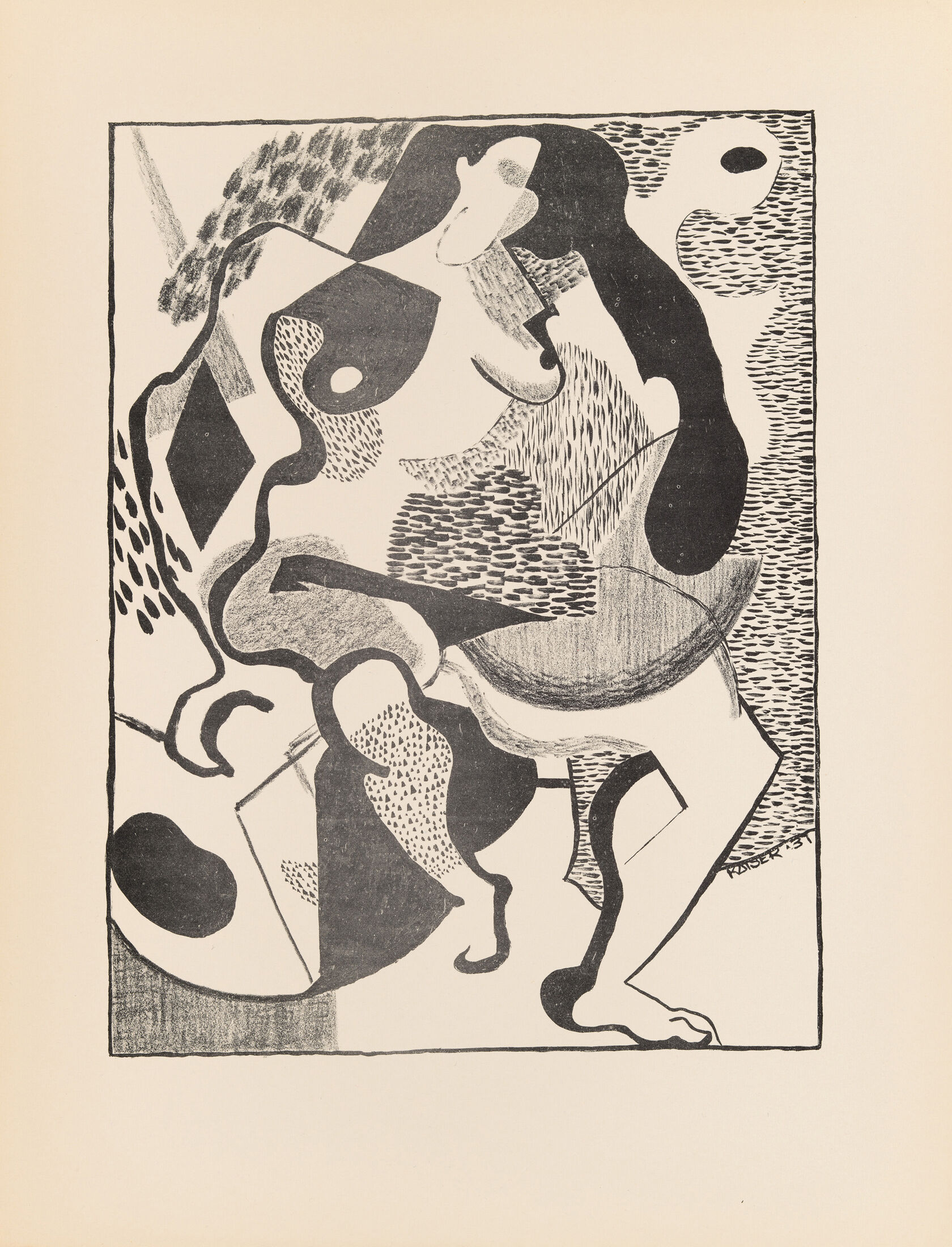

In April 1937 the AAA opened its first exhibition at the Squibb Galleries in midtown Manhattan, featuring work by its thirty-nine founding members, about a quarter of whom were women. The group considered the show a success: during its two-week run, over 1,500 people attended the exhibition and 500 editions were sold of a portfolio of members’ lithographs. Created as a means of sharing the group’s work broadly, raising revenue, and generating publicity, the portfolio contains a single print from thirty of the co-founders. Like the exhibition, the prints (seven of which are on view in Labyrinth of Forms) demonstrated the group’s catholic embrace of abstract approaches, as can be seen in comparing the entries from Gertrude Greene and Ray Kaiser, to cite just two examples. While the show was largely greeted with negative criticism typical of the time—reviewers charged the artists with being boring, decorative, derivative, and disconnected from reality—it still garnered significant press attention. Charmion von Wiegand, in a rare positive review, described the show as demonstrating the potential for this art to develop in the United States. An artist herself, von Wiegand became instrumental to the acceptance and understanding of abstraction in this country through her articles for New Masses and Art Front (among other publications), catalogue texts, and English translations of Piet Mondrian’s writings, along with exhibitions that she organized.Artist Harry Holtzman, who inherited Mondrian’s estate, published von Wiegand’s translations without giving her credit. As she wrote to her father, “The essays and translation I worked on with Mondrian have now been published by [Holtzman] . . . without giving me the slightest credit for months of labor. . . . My lawyer wanted me to sue, but it would have made an unpleasant situation and I might have been criticized. There was nothing to get out of a suit but a headache and annoyance.” Charmion von Wiegand to Karl von Wiegand, May 4, 1945, quoted in Jennifer Newton Hersh, “Abstraction, Spiritualism, and Social Justice: The Art and Writing of Charmion von Wiegand” (PhD diss., City University of New York, 1998), 260.

The American Abstract Artists contributed significantly to the slow-growing acceptance of abstraction in the United States in the early 1940s, a fact often overlooked by histories of Abstract Expressionism. The group’s annual exhibitions helped accustom viewers to American abstraction, and the yearbooks that accompanied the 1938 and 1939 exhibitions—the former featuring essays by Mason and Bengelsdorf—were among the crucial texts that provided a theoretical framework for understanding this art. As the decade turned, many critics remained skeptical of American abstraction but applauded these artists’ devotion to it. Edward Alden Jewell of the New York Times conceded that “modern abstraction is not just a flash in the pan” and “appears to have come to stay.”Edward Alden Jewell, “Abstraction Once More to the Fore,” New York Times, February 16, 1941.Younger writers were more accepting, with Clement Greenberg heralding the AAA’s 1942 annual presentation as signaling the “future of abstract art in this country.”Clement Greenberg, “Abstract Art,” Art section, The Nation, May 2, 1942, 526.His review also noted a host of other exhibitions of abstract art concurrently on view, and indeed a number of spaces receptive to it opened in the late 1930s and 1940s, including the Guggenheim Foundation’s Museum of Non-Objective Painting, Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of This Century, Nierendorf Gallery, Pinacotheca (later the Rose Fried Gallery), Willard Gallery, Betty Parsons Gallery, and Wittenborn & Schultz, which was an important venue for modern prints. While male artists received more solo shows than their female counterparts, a few American women abstractionists did have individual exhibitions at these spaces and others in the 1940s. They participated regularly in group shows as well, and Peggy Guggenheim even devoted exhibitions specifically to women artists in 1943 and 1945.

Although greater opportunity to exhibit benefited American abstraction as a whole, the relevance of the AAA waned over the course of the 1940s. The outbreak of World War II and the arrival of European refugee artists further dimmed the group’s influence. Mondrian, László Moholy-Nagy, and Fernand Léger all became exhibiting members of the American Abstract Artists but did not advocate strongly for the organization—nor did they draw attention from other European art celebrities, particularly the Surrealists, who had an immediate aesthetic and social impact in New York. Additionally, a number of members, including founders Bengelsdorf and Kaiser, left the cooperative in the 1940s in part because of the well-substantiated perception that it had abandoned a broad interpretation of abstraction in favor of strictly geometric work.

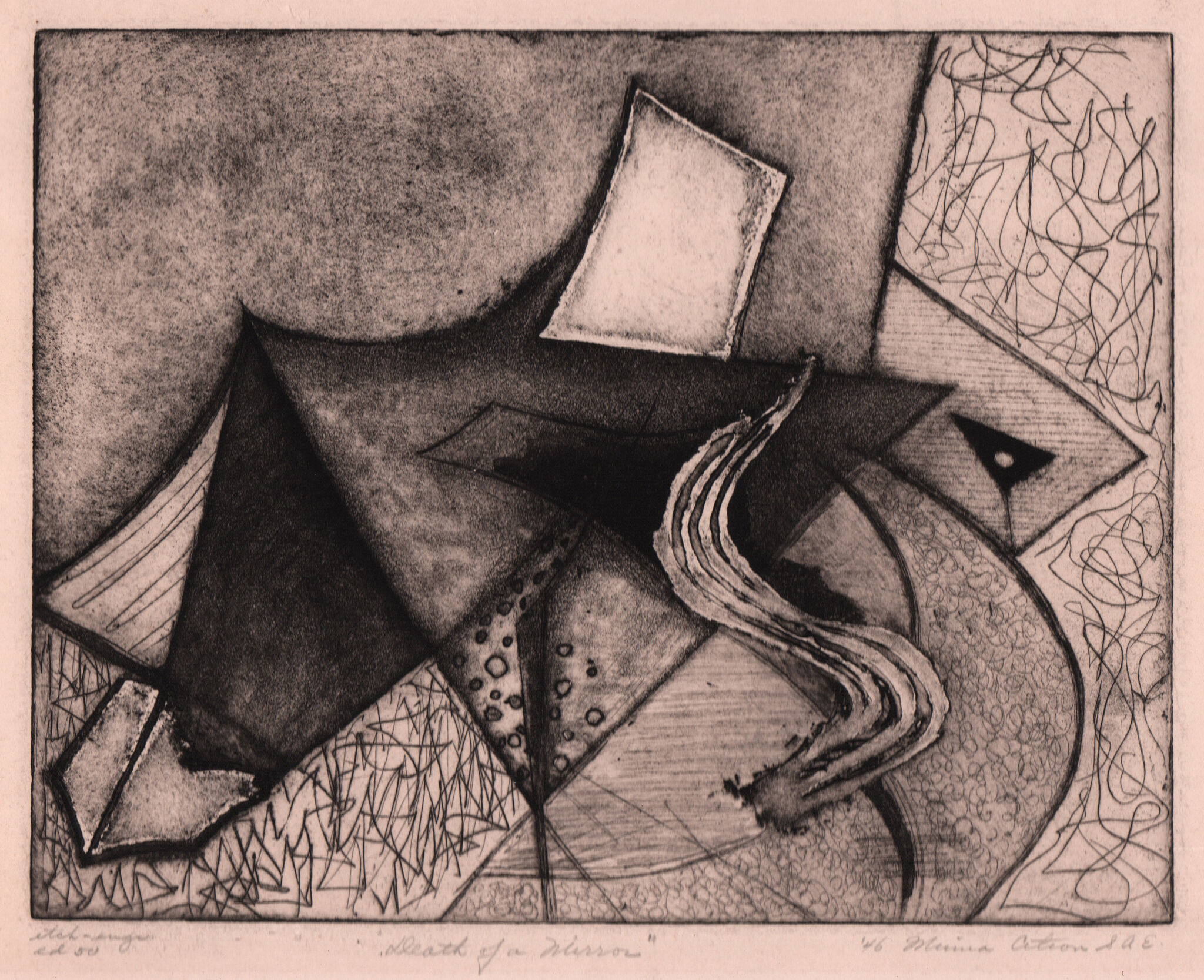

The larger community of American abstractionists remained committed to pursuing divergent styles and innovative methods throughout the 1940s, however. In New York, another mutually supportive avant-garde community developed at Atelier 17, a printshop founded in Paris by Stanley William Hayter that moved to the United States in 1940. The studio, described by Sue Fuller as “the cell of a revolution,” encouraged technical and formal invention, a marriage that produced truly modern artworks.Christina Weyl, The Women of Atelier 17: Modernist Printmaking in Midcentury New York (New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 2019), 25.A democratic spirit pervaded and, with a limited market for both abstract works and modern prints, competition among artists was minimal. Well-established European émigrés worked alongside emerging American artists, collaboration and idea-sharing were guiding principles, and some 40 percent of the artists who worked at Atelier 17 in New York were women—including current and former members of the AAA. Their work and methods earned respect, and some, like Fuller and Terry Haass, took on leadership roles.Fuller was a studio monitor and master printer at Atelier 17 and Haass became the studio’s co-director in 1950 when Hayter returned to Paris. Christina Weyl has conducted extensive research on the role of women at Atelier 17, including determining the number of women participants. I am grateful to her for discussing this topic with me during the early stages of this project. For further reading see Weyl, The Women of Atelier 17. Several women who produced prints at Atelier 17 in New York have work featured in Labyrinth of Forms, including Minna Citron, Dorothy Dehner, Perle Fine, Teresa d’Amico Fourpome, Sue Fuller, Terry Haass, Alice Trumbull Mason, Norma Morgan, Louise Nevelson, Irene Rice Pereira, and Anne Ryan. Barbara Olmsted, whose work is also on view in the exhibition, worked at Atelier 17 in Paris before it moved to the United States.The workshop specialized in intaglio—a printmaking process in which lines and shapes are incised into metal plates—and artists there revived, expanded, and invented techniques within the field. Atelier 17’s artists are credited with a broader use of soft-ground etching, innovating new methods for color printing, exploring the sculptural applications of embossing, and rediscovering sugar-lift etching, which Fuller managed through a combination of art historical research and experiments in her kitchen. Many works produced at the printshop employed a number of strategies in one object, as in Minna Citron’s Death of a Mirror. The contributions women made to printmaking at Atelier 17 were paralleled across the country in California, where Dorr Bothwell became an early advocate for fine art screenprinting and Elise and June Wayne—working with printmaker Lynton Kistler—produced early examples of fine art lithography, with Wayne in particular pushing Kistler toward technical innovation.

Some artists who worked at Atelier 17 would come to be identified with Abstract Expressionism, including Perle Fine, as well as the marquee figures Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, and Mark Rothko. These individuals were among the many artists working in a variety of abstract approaches in the 1940s, but by 1950 Abstract Expressionism solidified into an identifiable, marketable, and highly masculine movement. Male artists in 1949 had formed the Club—which initially prohibited women—and the art world’s social culture began to revolve around alcohol. As artist Virginia Admiral described it, the 1930s did not have a “cult of men” but “the macho drinking scene began in the 1940s, and of course, it was worse in the 1950s.”Siobhan M. Conaty, “Art of This Century: A Transitional Space for Women,” in American Women Artists, 1935–1970, ed. Langa and Wisotzki, 35.Museums and writers embraced this group, with articles in the popular press appearing as early as 1947. Such seals of approval spurred a new wave of collectors to buy contemporary American art, resulting in an increasingly commercialized and competitive business that ignored other (and earlier) modes of American abstraction and devalued art made by women. If they had gallery representation, women artists often felt unsupported by male colleagues—and sometimes even by female dealers: gallerist Samuel Kootz once said he would not show women because “they were too much trouble.”In 1991 in a recorded session at the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, Clement Greenberg recounted Samuel Kootz making this remark. See Ann Eden Gibson, Abstract Expressionism: Other Politics (New Haven, CT, and London: Yale University Press, 1997), 202n17.Within this environment, a plurality of styles was tacitly discouraged, gender bias was enforced, and the mechanisms for artistic recognition—exhibitions, critical and historical writing, and institutional sales—all but disappeared for most women, resulting in sustained marginalization. With their work overlooked contemporaneously, the subsequent understanding of it in art history was diminished. Since the 1970s, feminist art historians, curators, and gallerists have worked to correct this oversight, leading to the reevaluation of many women artists’ output and careers. Certain figures—like Louise Nevelson and Lee Krasner—have been the subject of important scholarly texts and monographic exhibitions, securing their places in the canon. Critical reexaminations of Abstract Expressionism have asserted a broader history of the movement that is more inclusive of women (and people of color). Recent exhibitions like the Denver Art Museum’s Women of Abstract Expressionism (2016) and books such as Mary Gabriel’s Ninth Street Women (2018) have built on the work of art historians like Ann Eden Gibson, Griselda Pollock, and Anne M. Wagner, among others, to popular acclaim. Christina Weyl’s research and writing on female printmakers has also added importantly to scholarly reassessments. However, the role of women in the foundational years of American abstraction, particularly before 1945, remains under-studied, in no small part because of art historical norms that privilege painting and sculpture over works on paper and perpetuate a division between prewar and postwar modernism. More work remains to be done, but Labyrinth of Forms: Women and Abstraction, 1930–1950 and this essay are steps toward expanding and correcting the historical record—and toward introducing new generations to the breadth and complexity of modern drawings and prints.