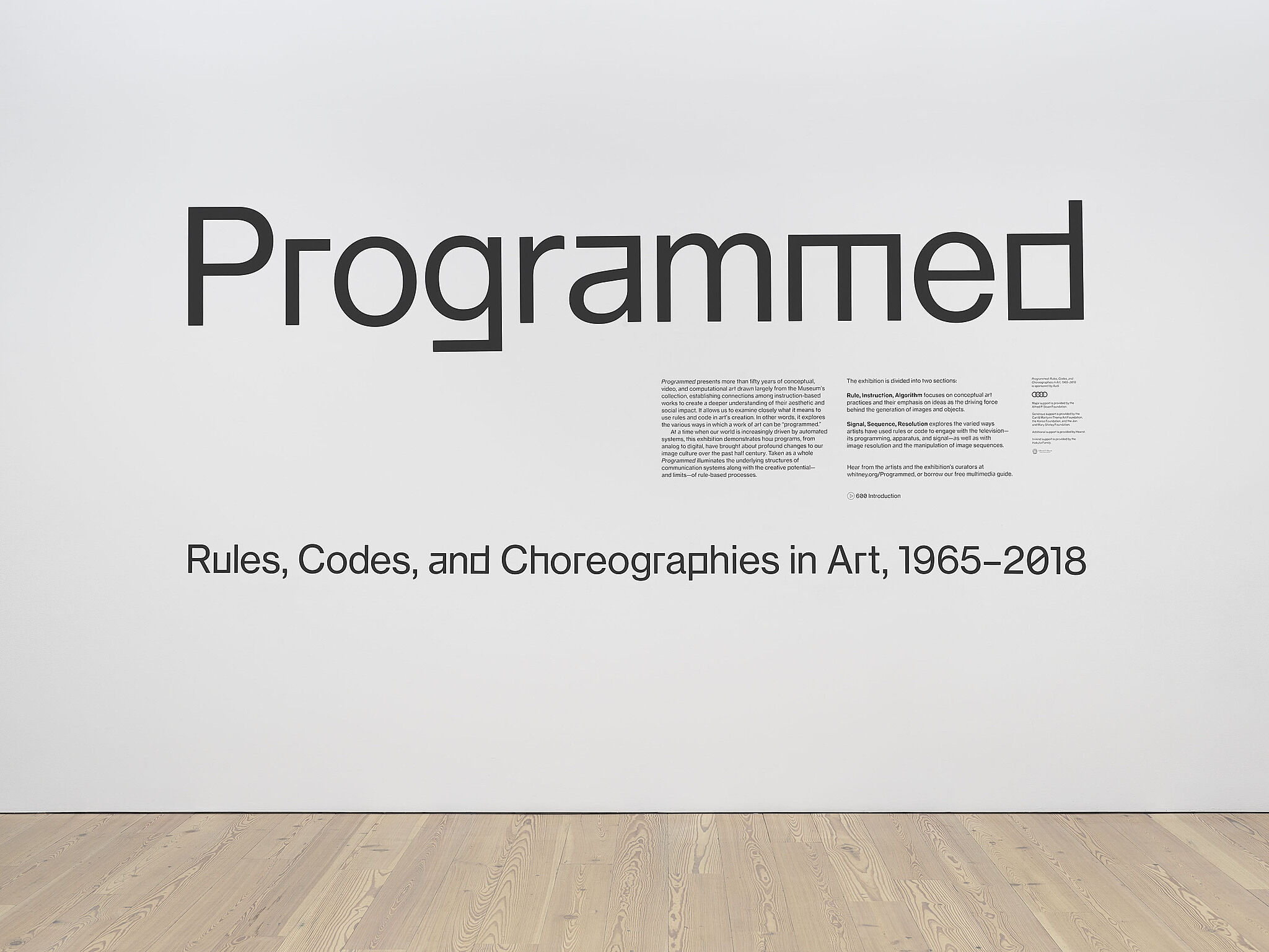

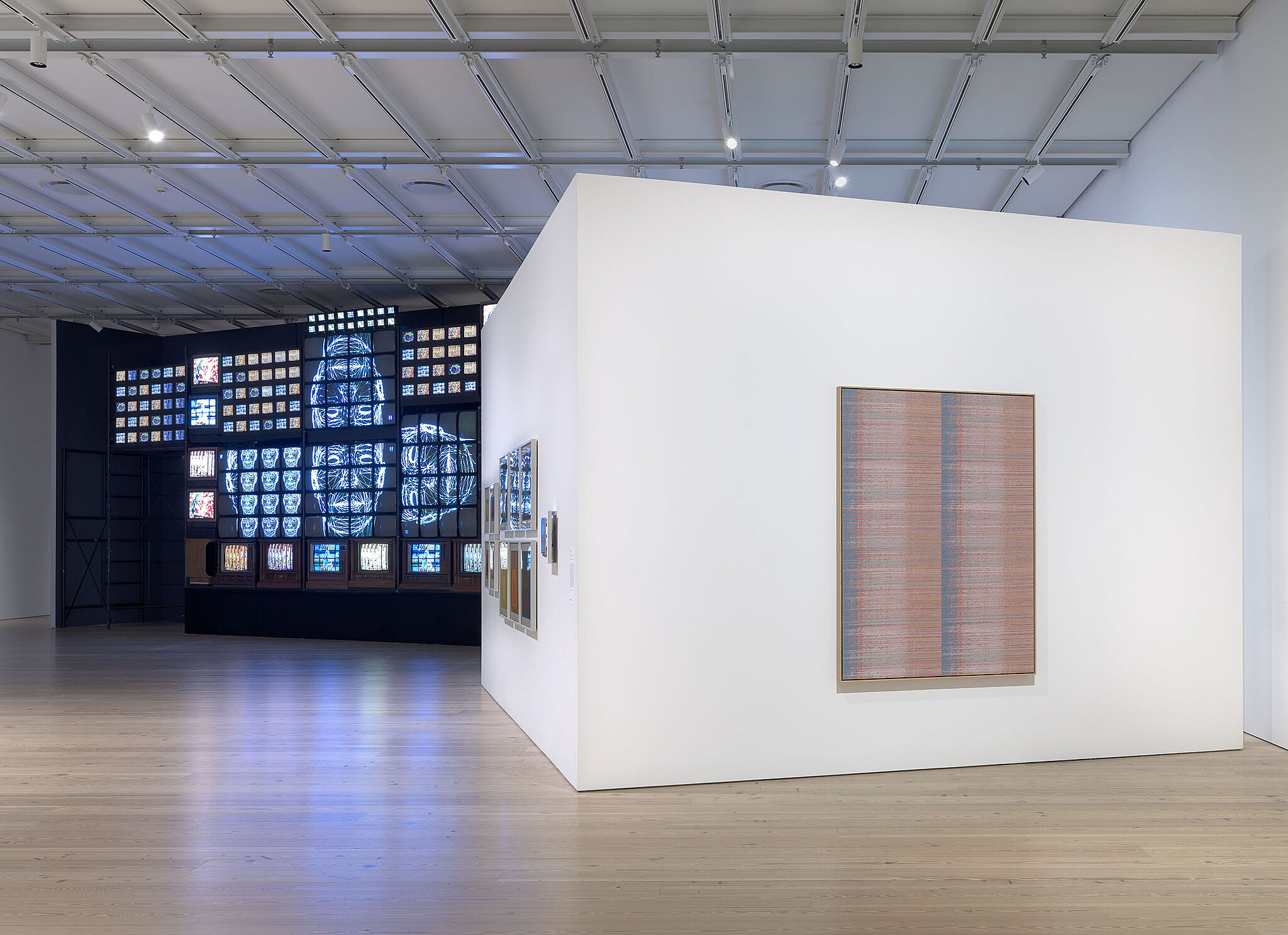

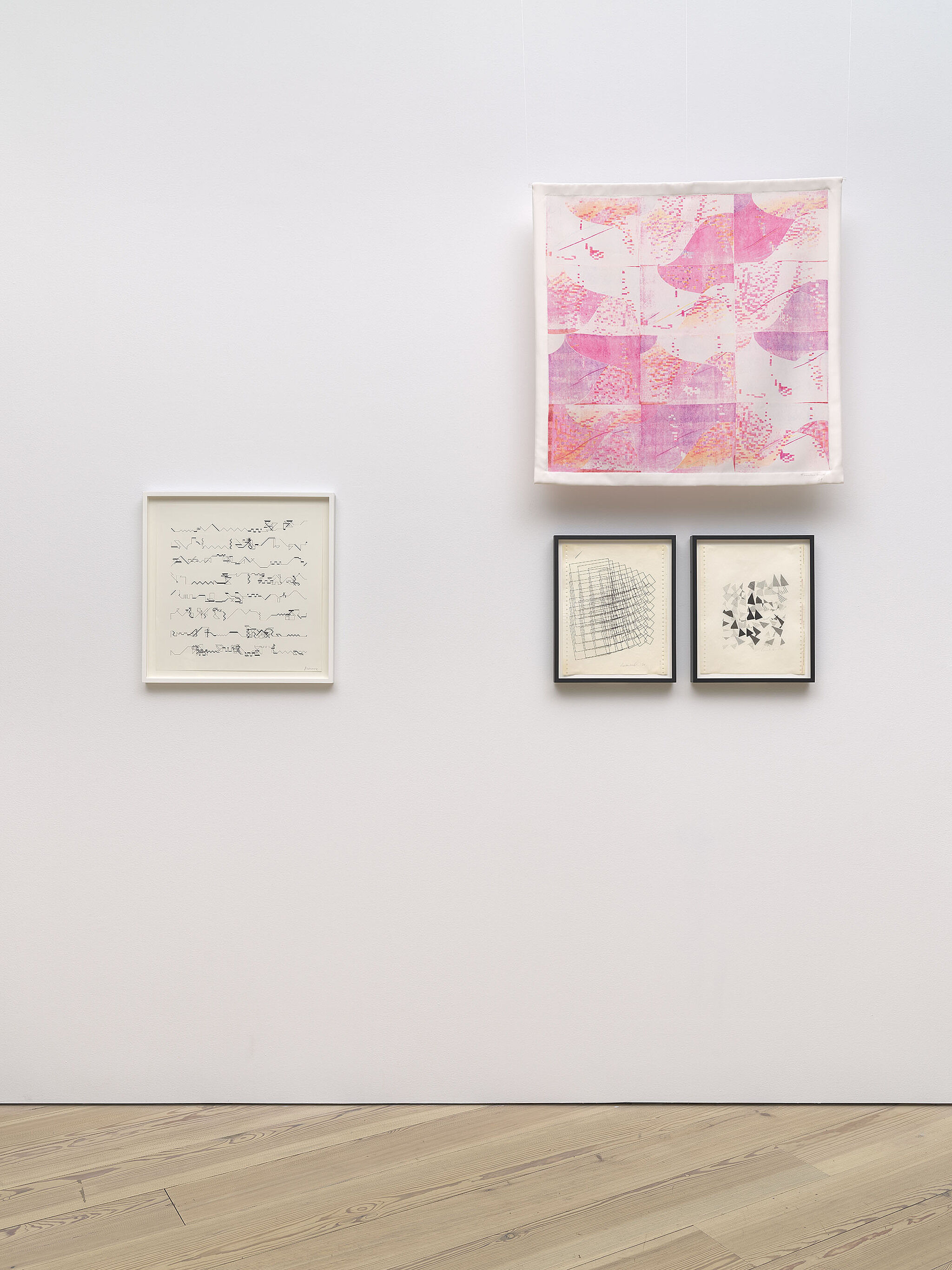

Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018

Sept 28, 2018–Apr 14, 2019

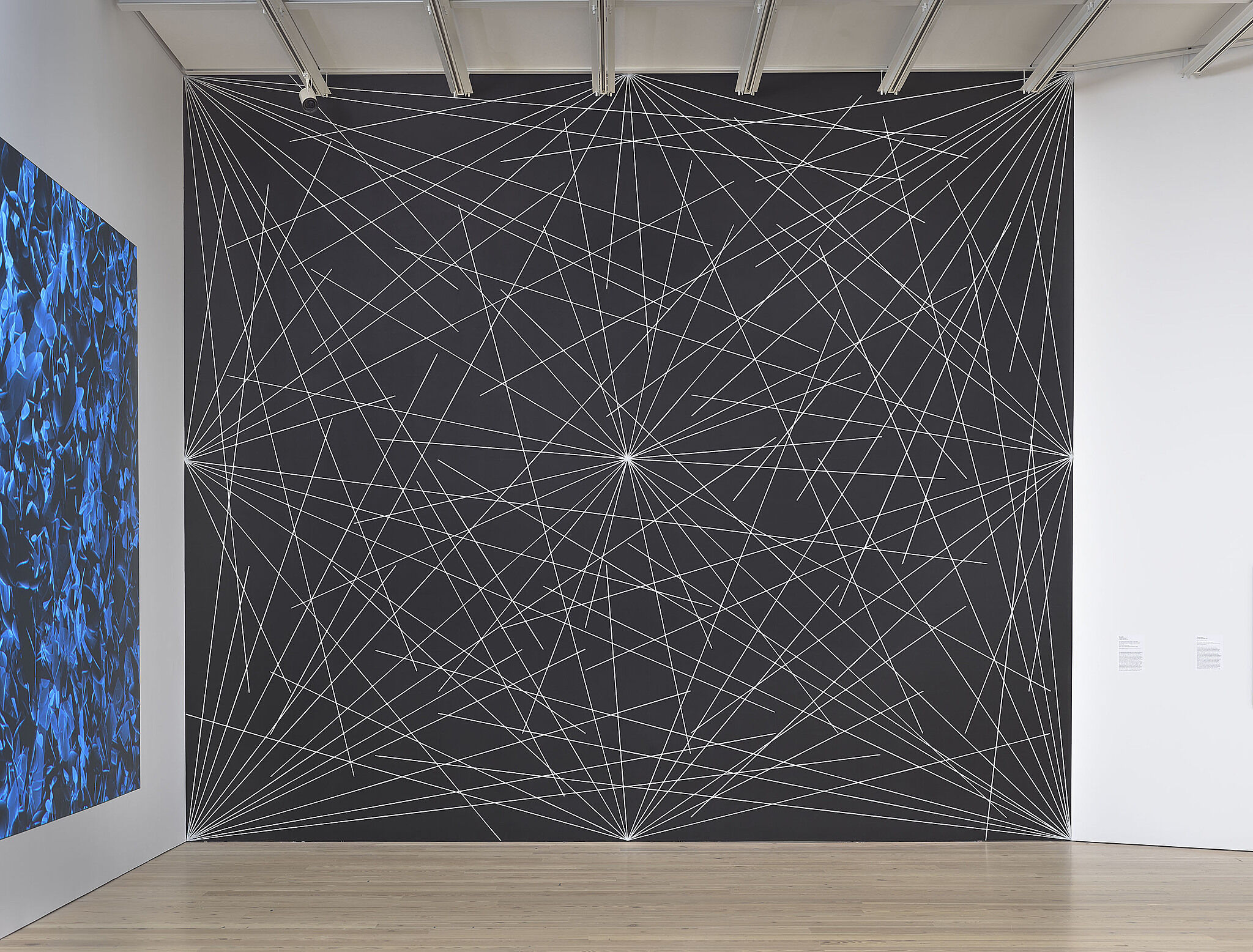

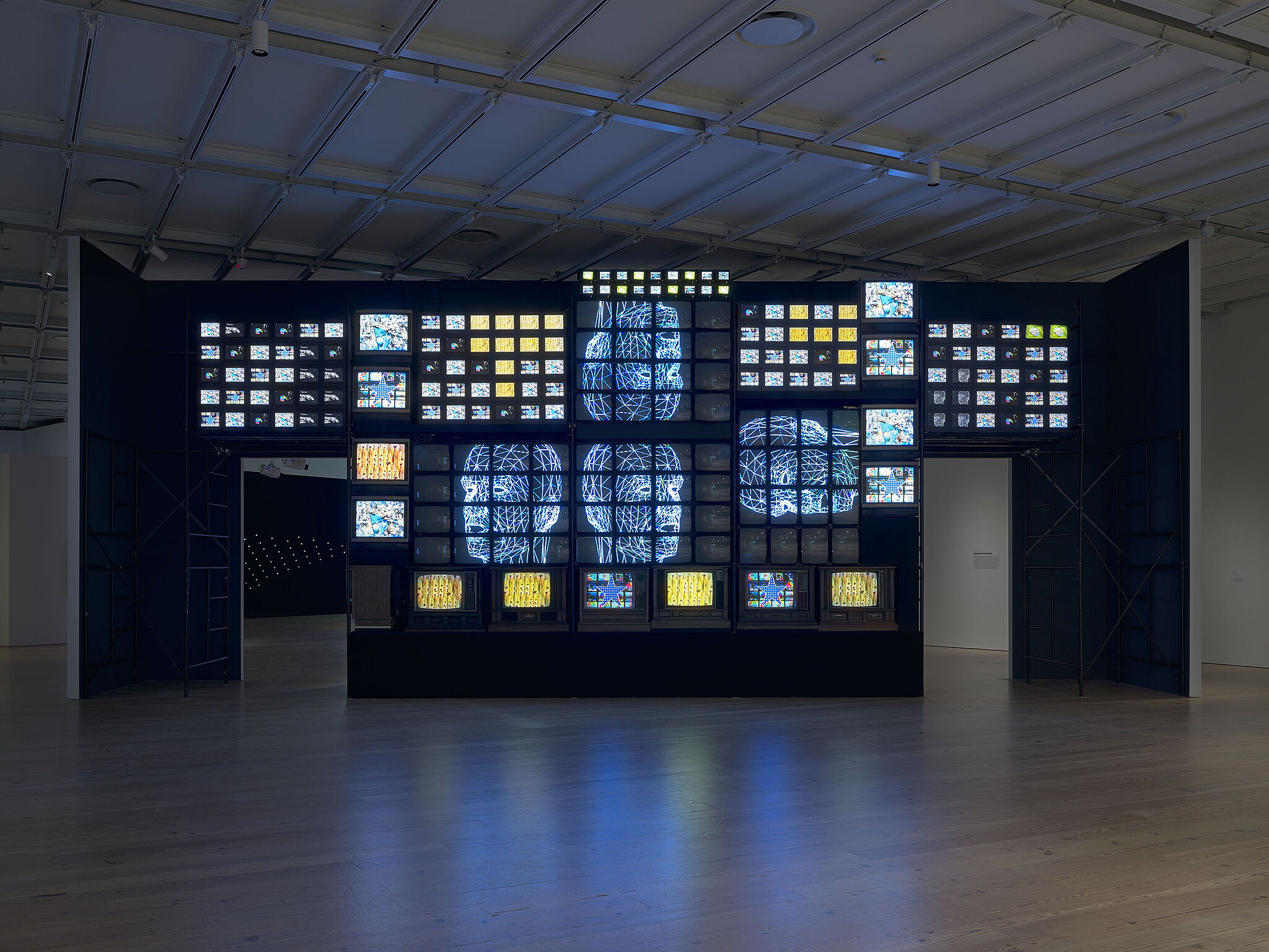

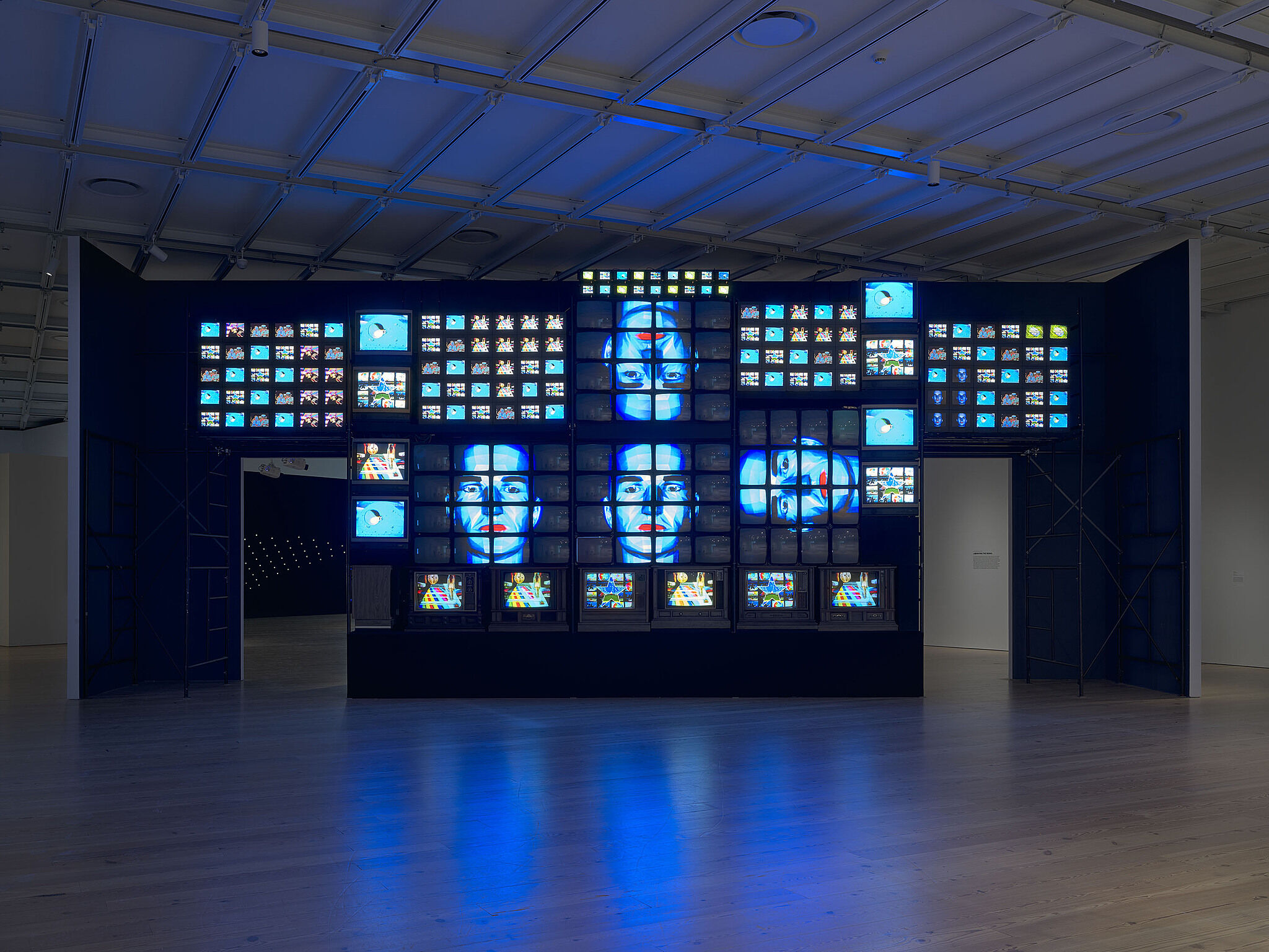

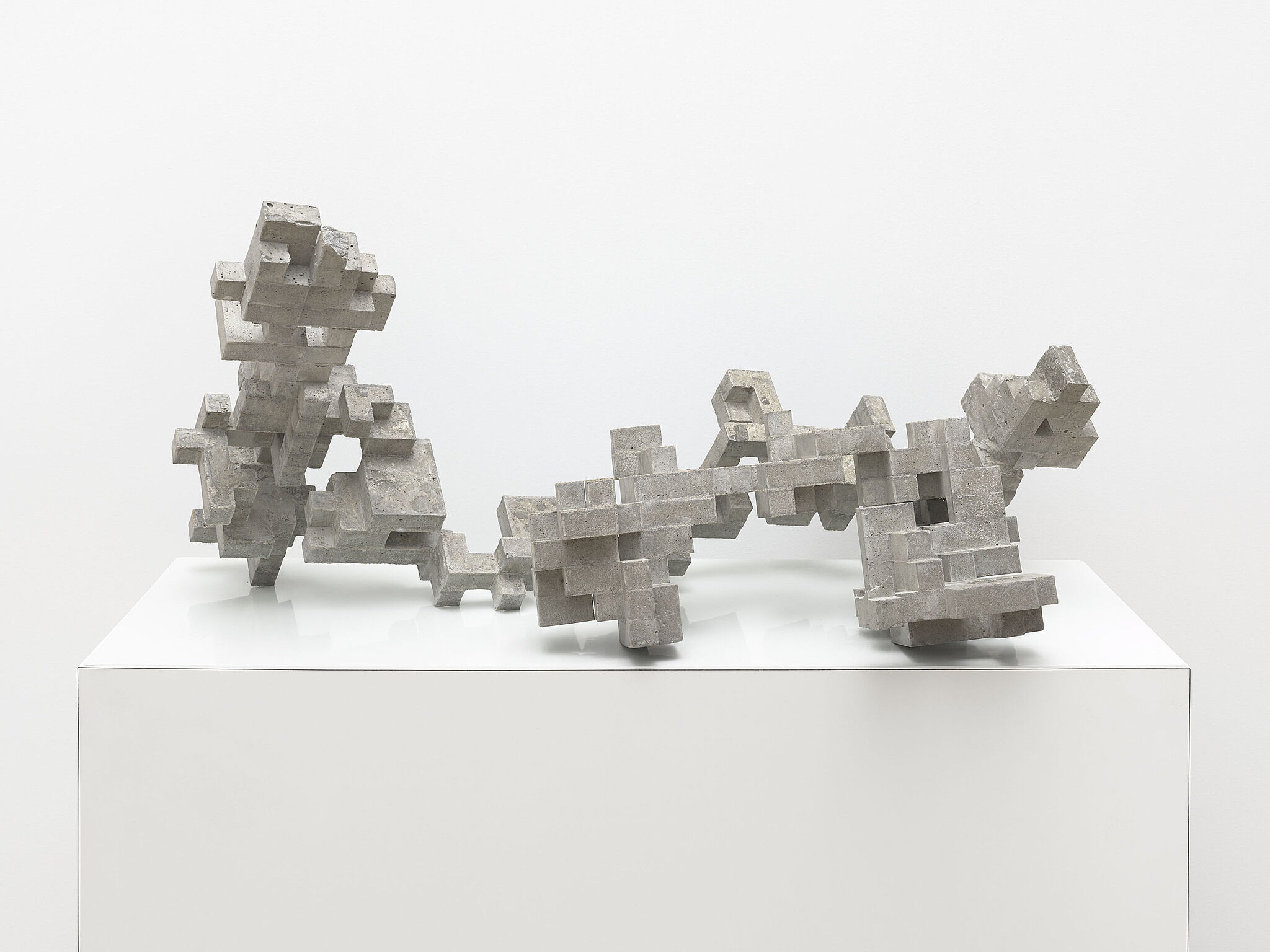

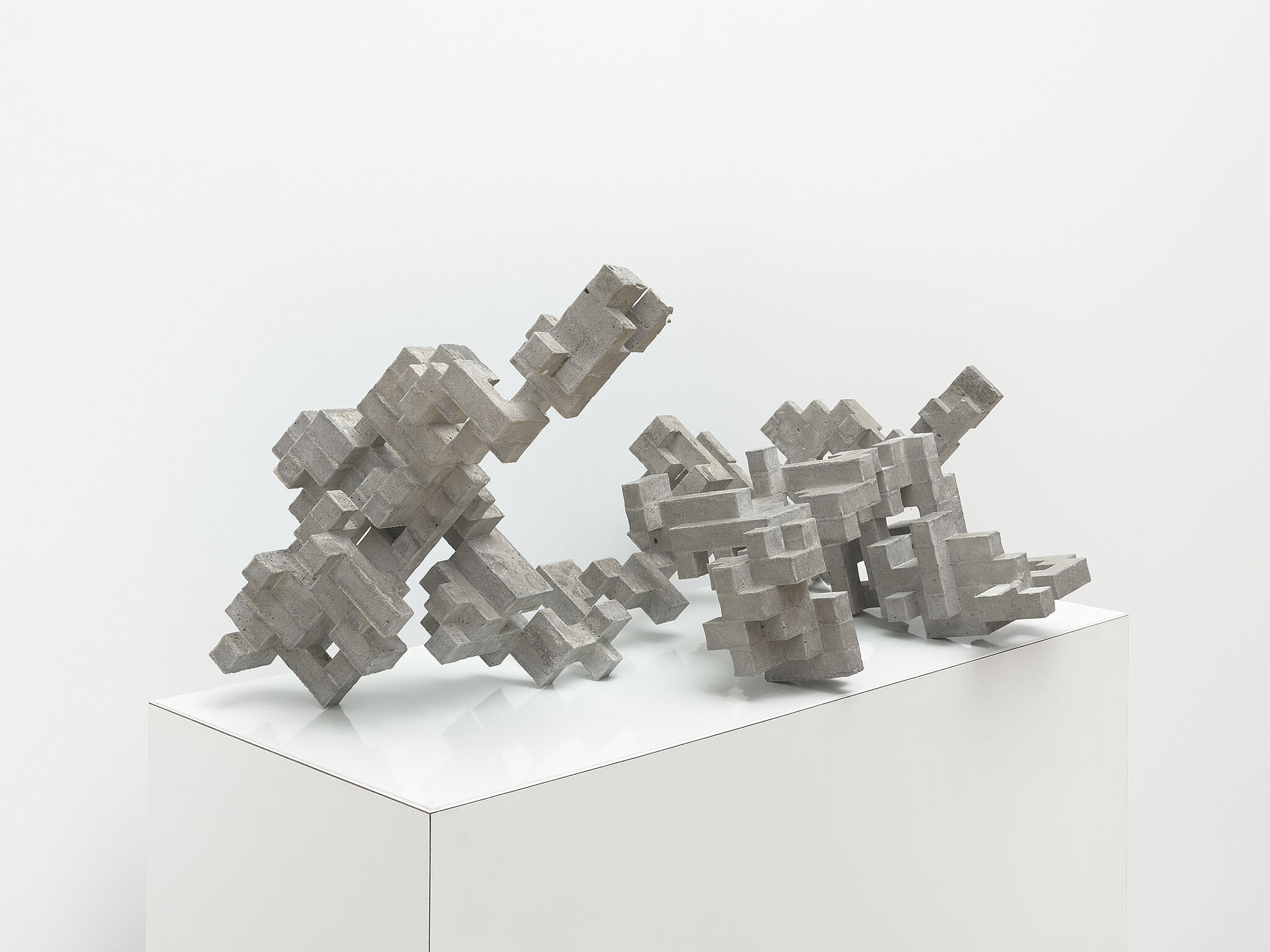

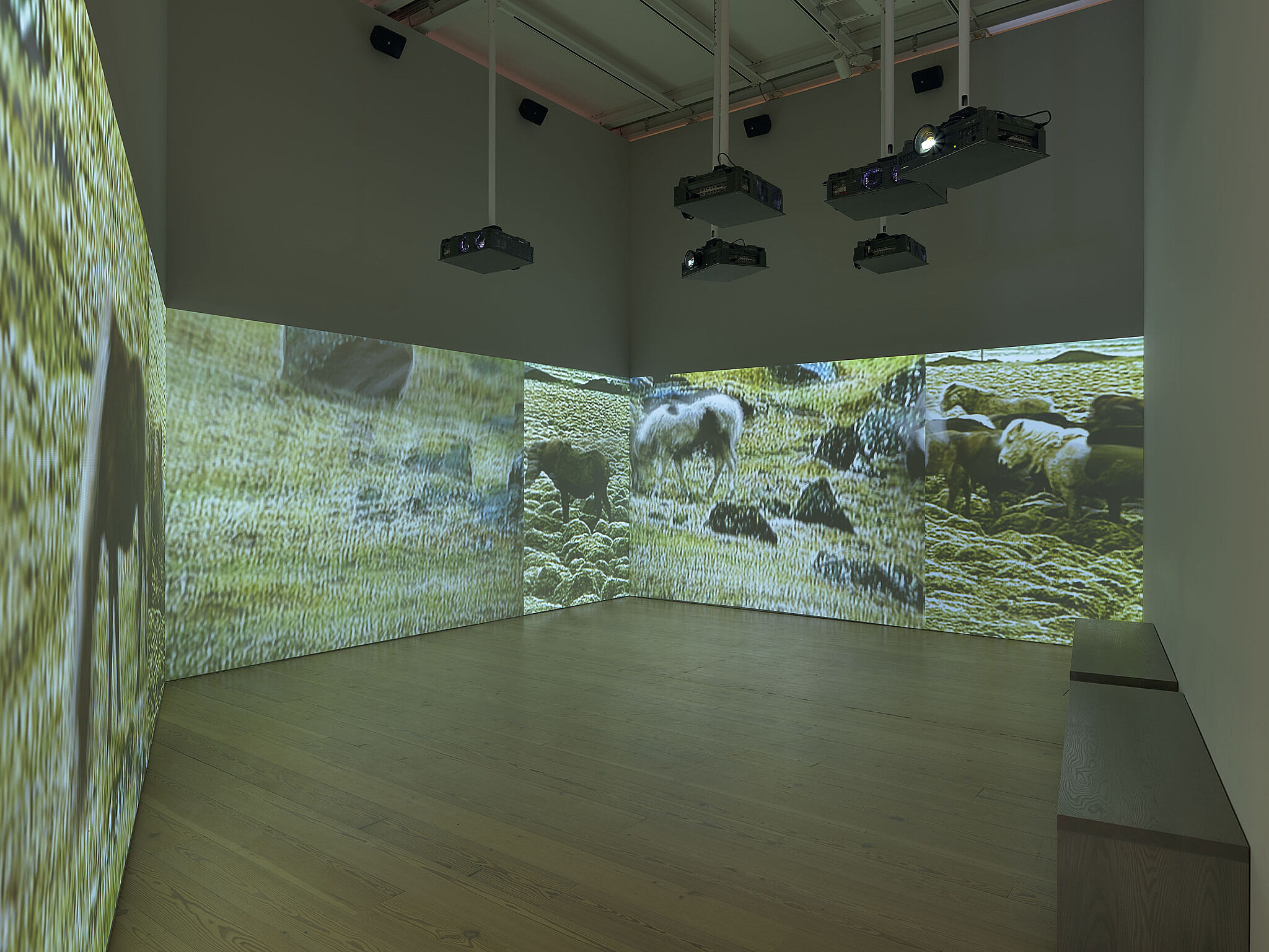

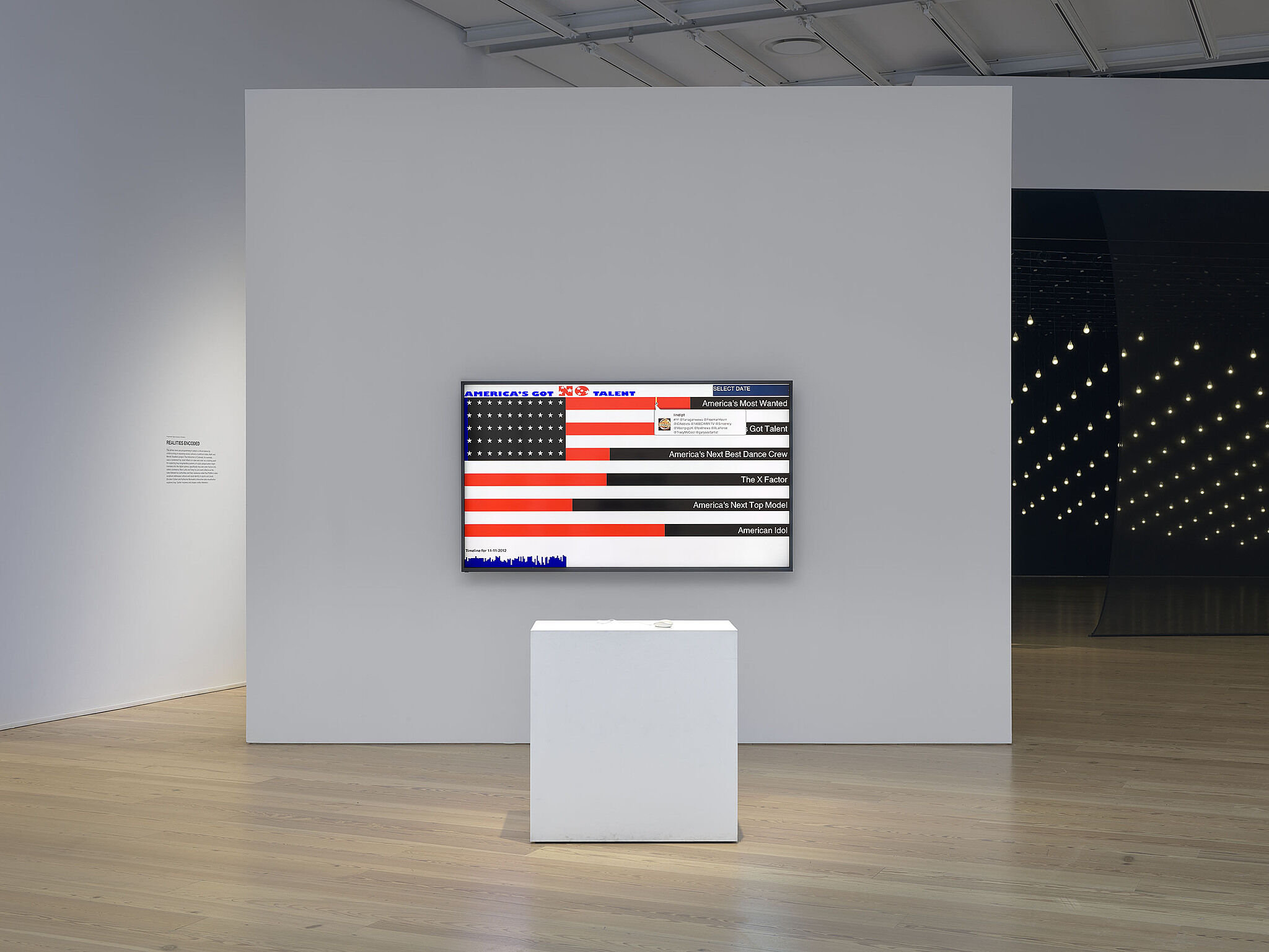

Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018 establishes connections between works of art based on instructions, spanning over fifty years of conceptual, video, and computational art. The pieces in the exhibition are all “programmed” using instructions, sets of rules, and code, but they also address the use of programming in their creation. The exhibition links two strands of artistic exploration: the first examines the program as instructions, rules, and algorithms with a focus on conceptual art practices and their emphasis on ideas as the driving force behind the art; the second strand engages with the use of instructions and algorithms to manipulate the TV program, its apparatus, and signals or image sequences. Featuring works drawn from the Whitney’s collection, Programmed looks back at predecessors of computational art and shows how the ideas addressed in those earlier works have evolved in contemporary artistic practices. At a time when our world is increasingly driven by automated systems, Programmed traces how rules and instructions in art have both responded to and been shaped by technologies, resulting in profound changes to our image culture.

The exhibition is organized by Christiane Paul, Adjunct Curator of Digital Art, and Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, Melva Bucksbaum Associate Director for Conservation and Research, with Clémence White, curatorial assistant.

Please be warned this exhibition includes video and projection with a flashing light effect.

Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018 is sponsored by Audi

Major support is provided by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Generous support is provided by the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Art Foundation, the Korea Foundation and the Jon and Mary Shirley Foundation.

Additional support is provided by Hearst.

In-kind support is provided by the Hakuta Family.

Signal, Sequence, Resolution:

Liberating the Signal

5

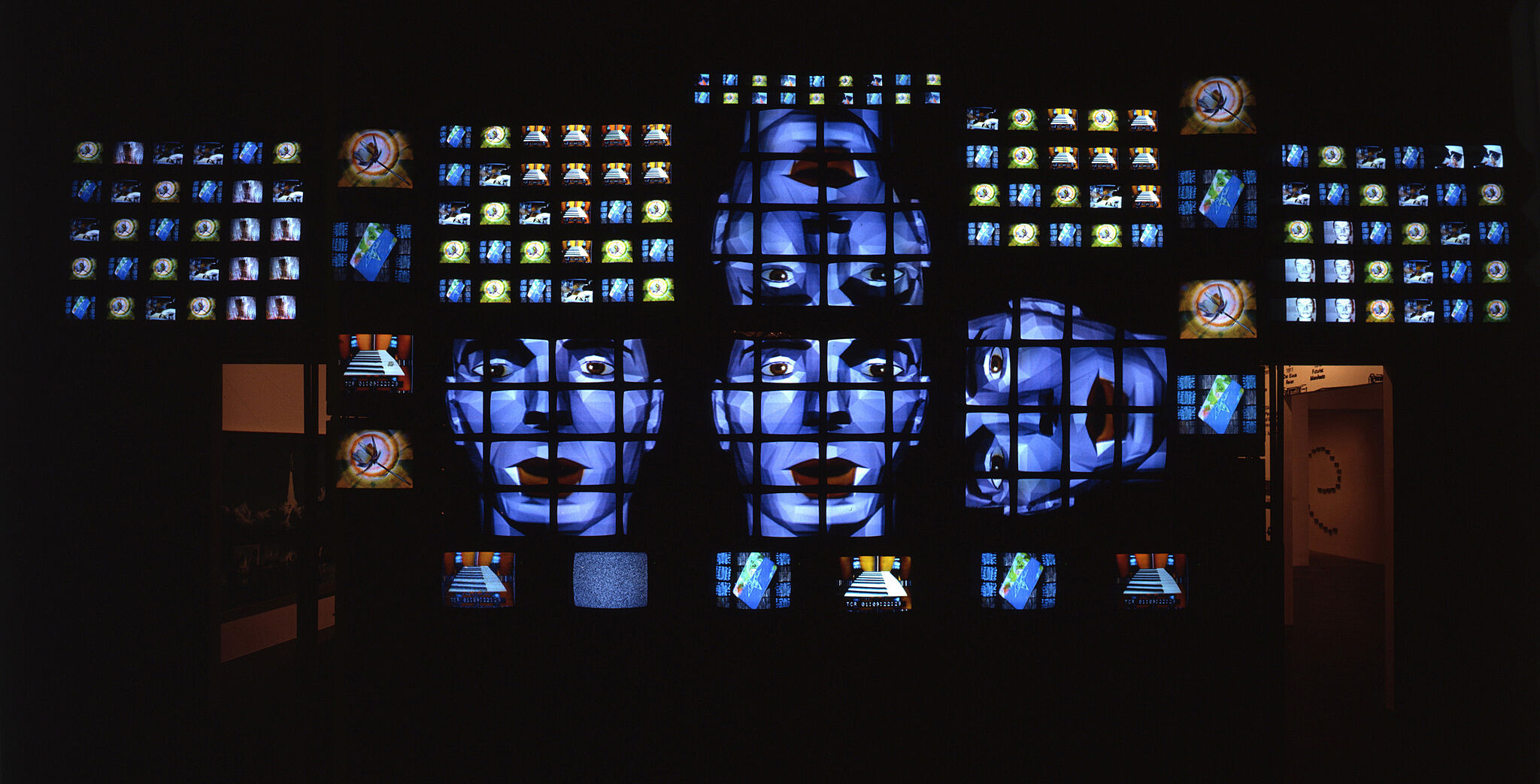

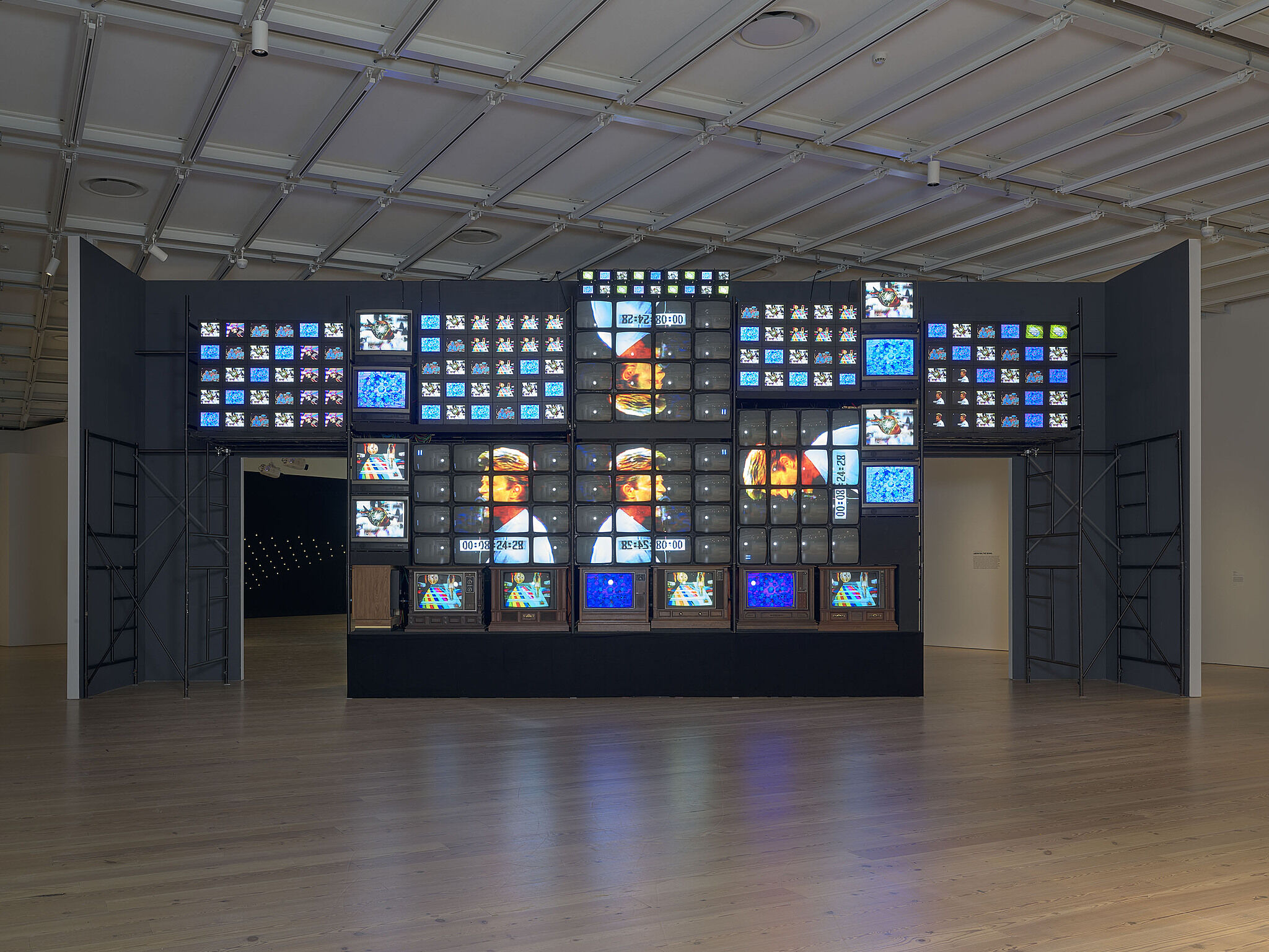

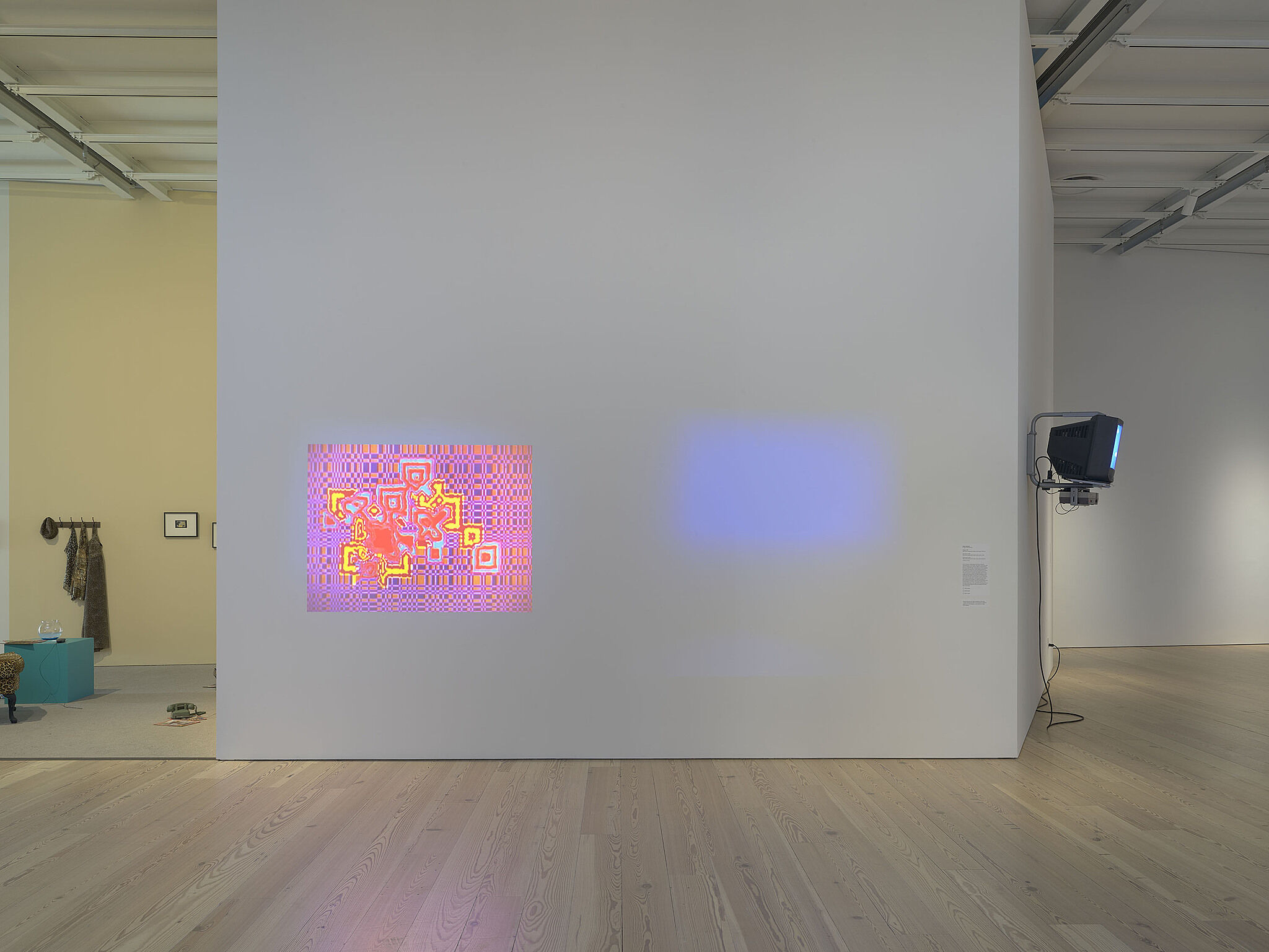

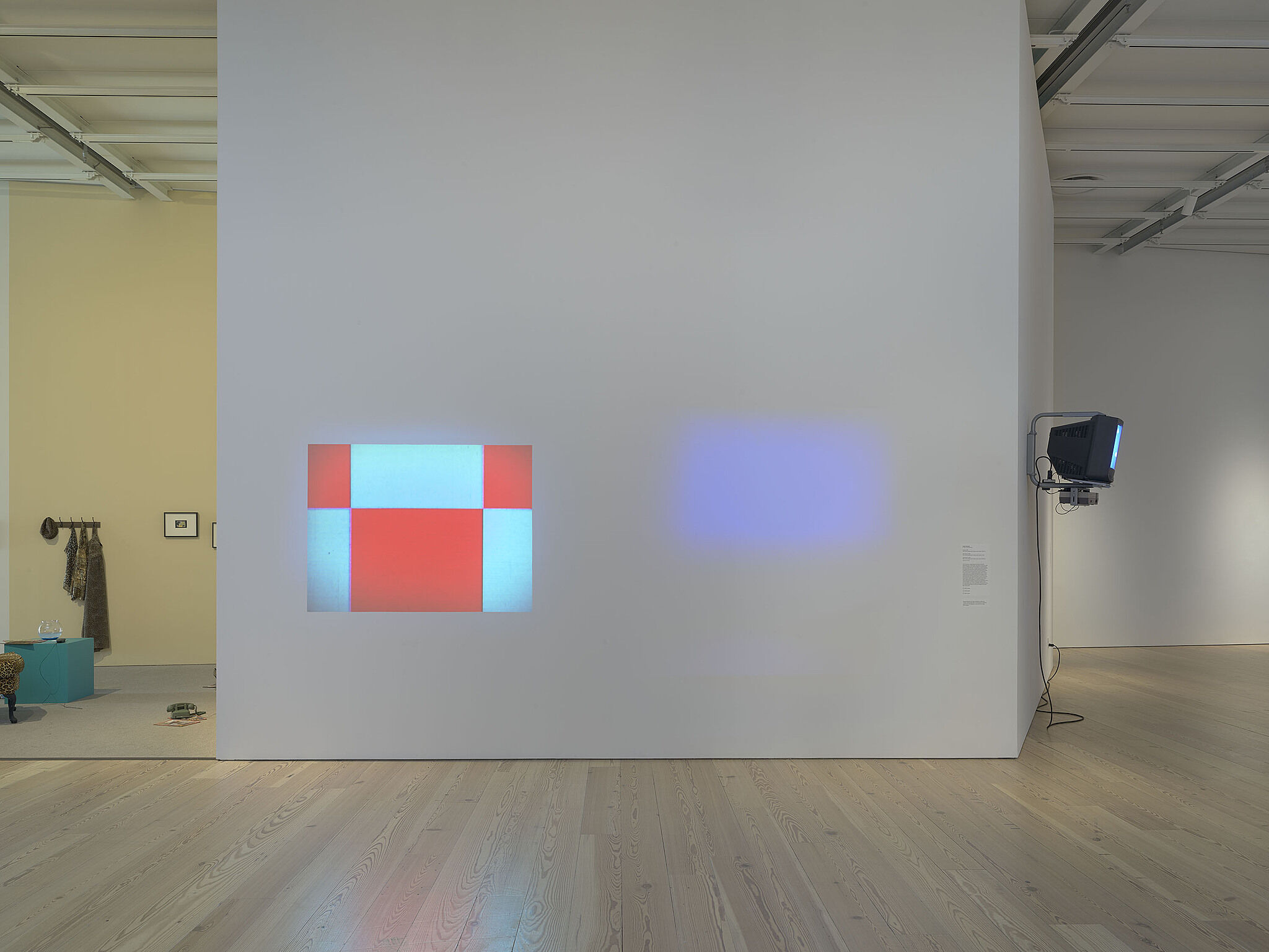

The artists in this grouping use electronic or digital signals as their material but subvert the signals’ intended function, thereby “liberating” them from their original purpose. In doing so, they draw attention to the potential for signals to be carriers of instructions and visual information. Nam June Paik’s Magnet TV creates visual effects by distorting a television’s electronic signal, while digitally manipulated signals are an element of Cory Arcangel’s Super Mario Clouds for which the artist reprogrammed a Nintendo cartridge to erase the sound and all visual elements except for the clouds from the iconic video game. Signal and image resolution are explored by Jim Campbell, who programs LEDs to create cinematic and spatial images in both a room-sized installation and screen-based works.

Earl Reiback, Thrust, 1969*

To make the works in his series of modified televisions, Earl Reiback detached and emptied the cathode-ray tube (CRT) monitor of a TV, scraped the light-emitting phosphorus from the inside of the screen, then inserted sculptural elements and added back the phosphorescent paint. The altered televisions become sculptural forms, drawing attention to the space of the monitor and the creation of images through electronic signals, and also playing with our perception of how images are projected.

*Installed as part of an earlier version of the exhibition.

Artists

- Josef Albers

- Cory Arcangel

- Tauba Auerbach

- Jonah Brucker-Cohen

- Jim Campbell

- Ian Cheng

- Lucinda Childs

- Charles Csuri

- Agnes Denes

- Alex Dodge

- Charles Gaines

- Philip Glass

- Frederick Hammersley

- Channa Horwitz

- Donald Judd

- Joseph Kosuth

- Shigeko Kubota

- Marc Lafia

- Barbara Lattanzi

- Lynn Hershman Leeson

- Sol LeWitt

- Fang-yu Lin

- Manfred Mohr

- Katherine Moriwaki

- Mendi + Keith Obadike

- Nam June Paik

- William Bradford Paley

- Paul Pfeiffer

- Casey Reas

- Earl Reiback

- Rafaël Rozendaal

- Lillian Schwartz

- James L. Seawright

- John F. Simon Jr.

- Steina

- Mika Tajima

- Tamiko Thiel

- Cheyney Thompson

- Joan Truckenbrod

- Siebren Versteeg

- Lawrence Weiner

Events

View all-

Ethics of Looking

Repeats

Saturday, April 27, 2019

4:30 pm -

Whitney Signs: Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018

Saturday, April 6, 2019

4–6 pm -

Member Night

Thursday, March 28, 2019

7:30–10 pm -

Verbal Description and Touch Tour: Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018

Friday, March 22, 2019

10–11:30 am

Mobile guides

“The hope was for me as an artist to lose control, and to have my control exist at the level of setting up the experiment.” —Ian Cheng

Hear directly from artists and curators on selected works from Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018.

Explore works from this exhibition

in the Whitney's collection

View 67 works

In the News

"How Artists Made Code Their Paintbrush"

—Science Friday

"Tamiko Thiel’s 'Unexpected Growth' is an augmented reality installation on the future of oceans and climate change."

—Hyperallergic

"The exhibit uses the Whitney’s own collection to explore how computational art has evolved and changed over the decades based on technology."

—Smithsonian

"Is a particularly urgent, relevant exhibition and a perfect setting in which to consider some of the most pressing questions of our time.”

—Sotheby’s Museum Network

"Programmed explores the limits of code-based art, looking at past generations of computational art and illustrating how the ideas of earlier works have developed to form new contemporary styles.”

—SVA NYC

“From early mathematical works, to Generative art, to digital art in a variety of media, the works in Programmed take many forms.”

—Art and Object

"Artists play and experiment with algorithms and technology, working within limits but achieving effects greater than the sum of their codes or instructions. The duality at play in this exhibition is as separable as the wave and particle natures of light. To recognize only one explanation would be reductive; to see both is beautiful.”

—Scientific American

“Paik captured both the allure and the futility of following events that happen so quickly they don't register before they're outdated.”

—Forbes