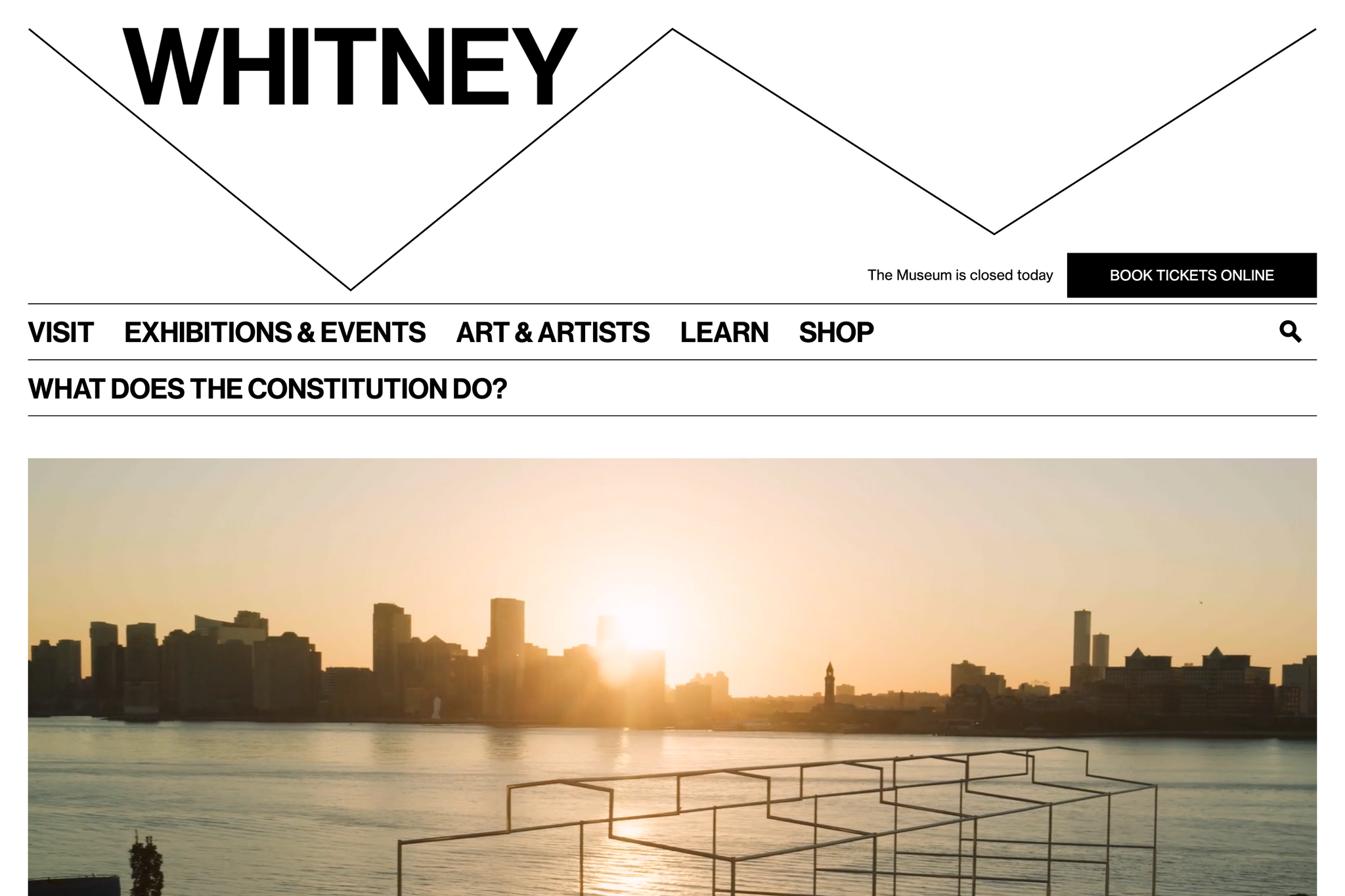

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept

Apr 6–Oct 16, 2022

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It’s Kept

The Whitney Biennial has surveyed the landscape of American art, reflecting and shaping the cultural conversation, since 1932. The eightieth edition of the landmark exhibition is co-curated by David Breslin, DeMartini Family Curator and Director of Curatorial Initiatives, and Adrienne Edwards, Engell Speyer Family Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs. Titled Quiet as It’s Kept, the 2022 Biennial features an intergenerational and interdisciplinary group of sixty-three artists and collectives whose dynamic works reflect the challenges, complexities, and possibilities of the American experience today.

Curatorial statement

By David Breslin and Adrienne Edwards

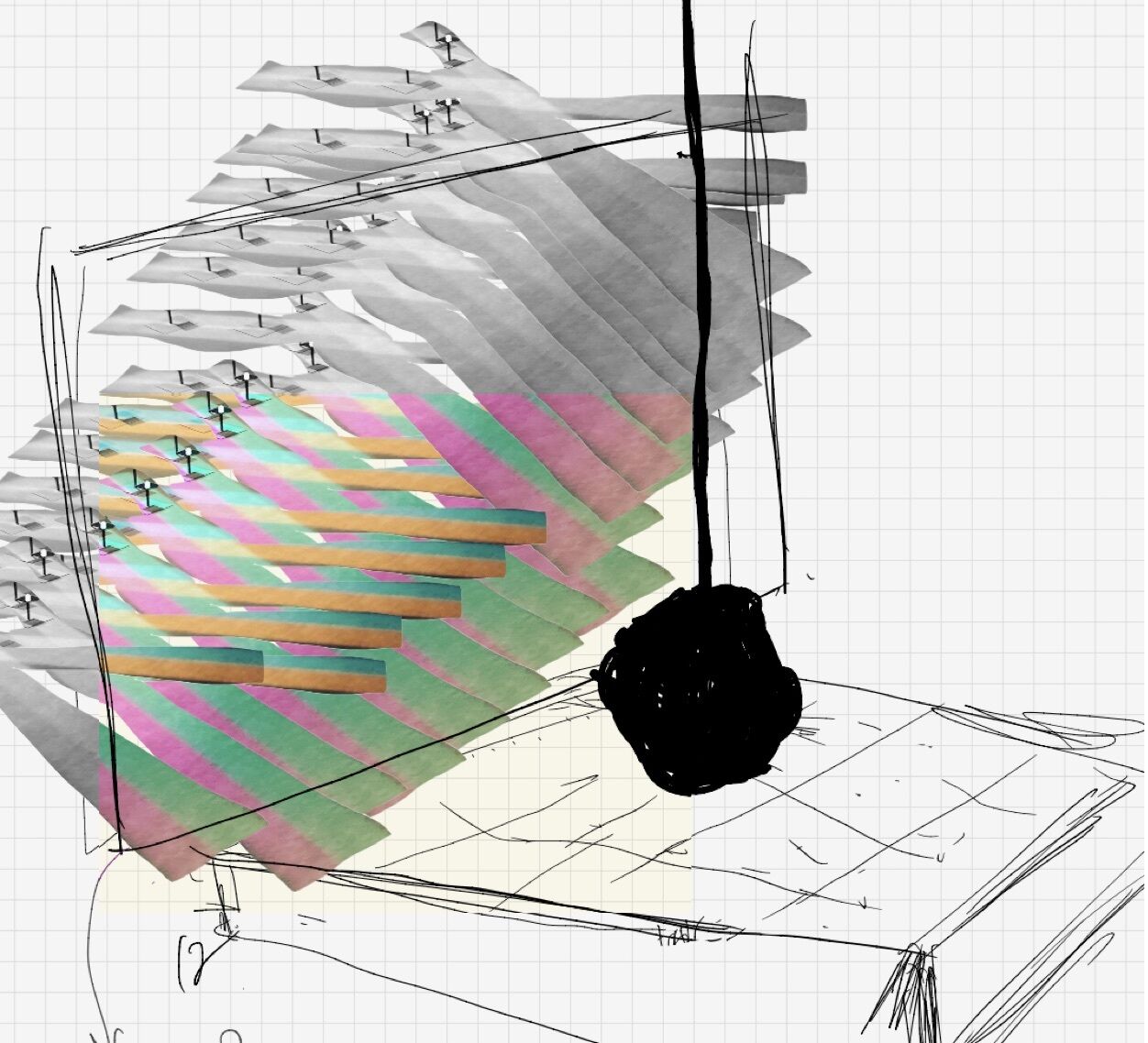

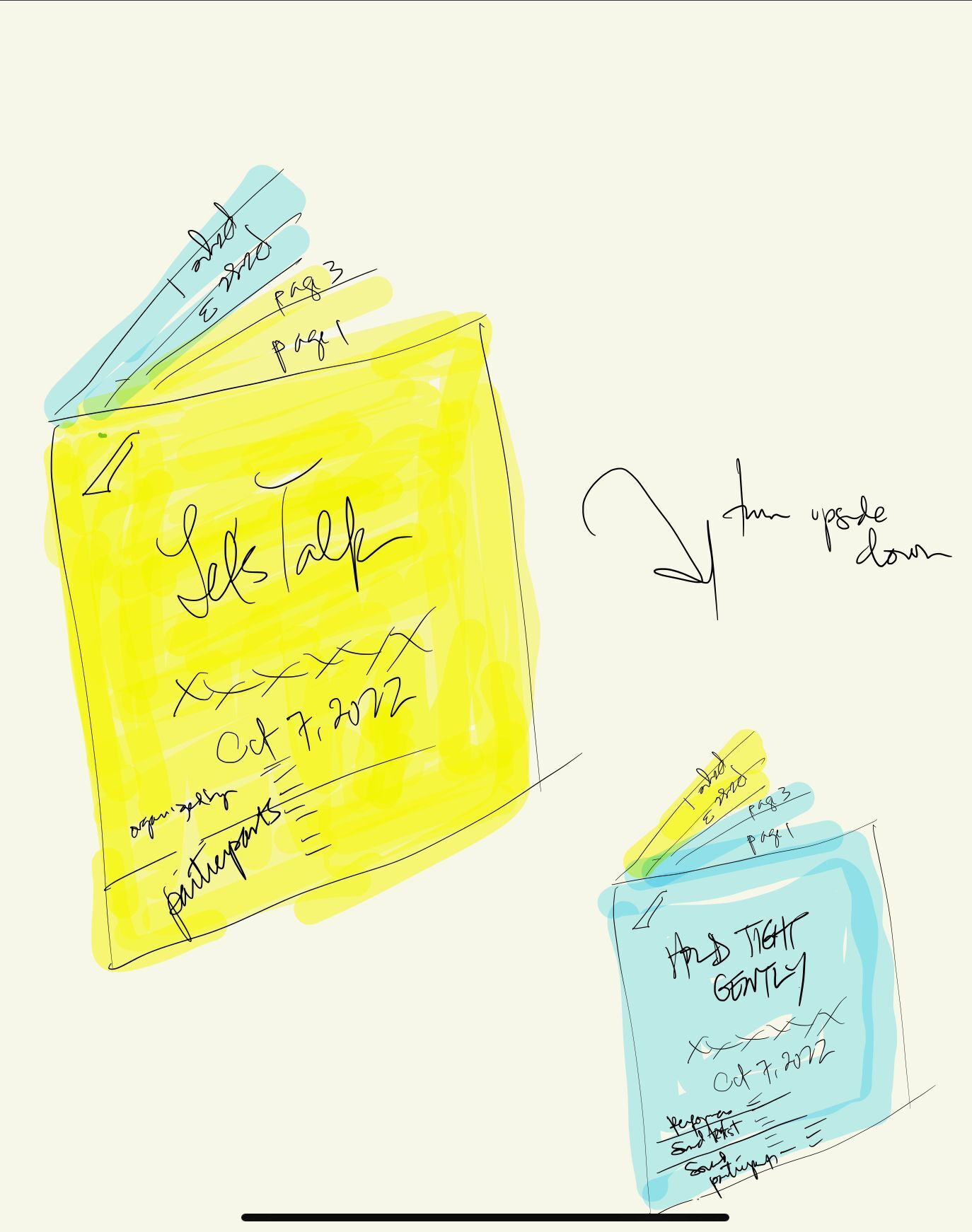

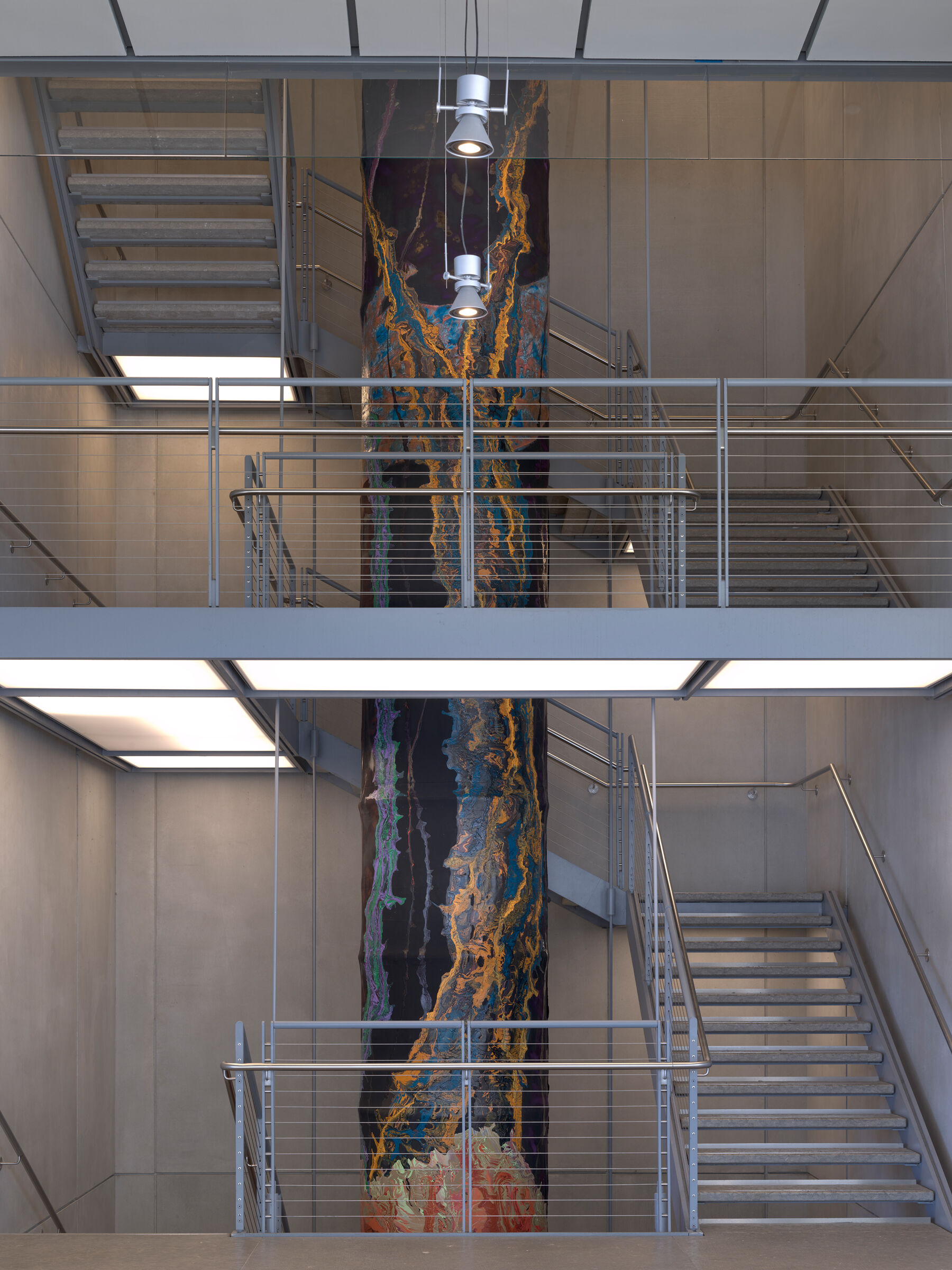

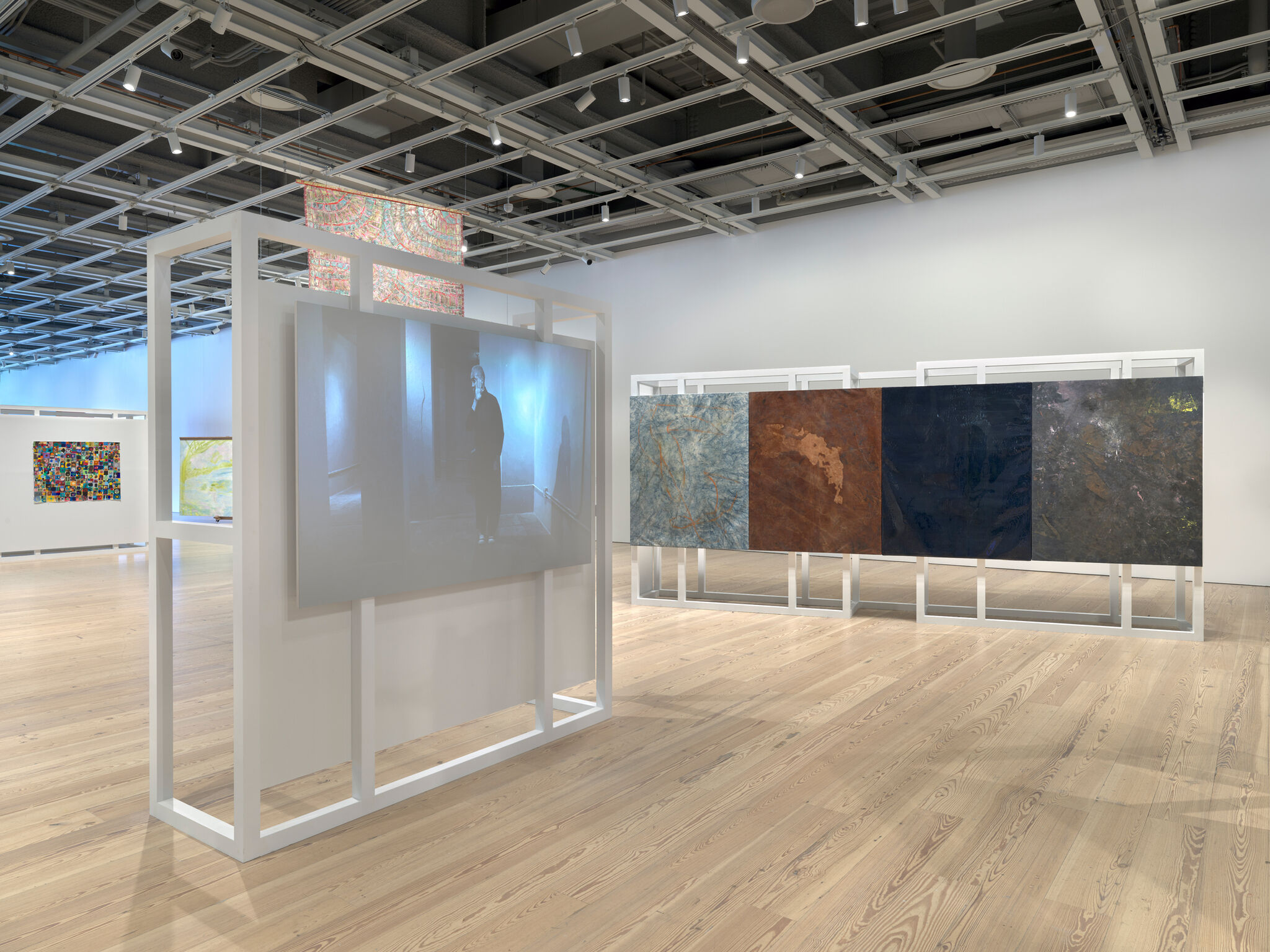

Since the start of the pandemic, time has expanded, contracted, suspended, and blurred—often in dizzying succession. We began planning this Biennial in late 2019: before Covid and its reeling effects, before the uprisings demanding racial justice, before the widespread questioning of institutions and their structures, before the 2020 presidential election. Although underlying conditions are not new, their overlap, their intensity, and their sheer ubiquity created a context in which past, present, and future folded into one another. We organized this Biennial to reflect these precarious and improvised times. Many artists’ contributions are dynamic, taking different forms during the course of the exhibition. Artworks change, walls move, and performances animate the galleries and surrounding objects. The spaces of the Biennial contrast significantly, acknowledging the acute polarity of our society. One floor is a labyrinth, a dark space of containment; another is a clearing, open and light filled.

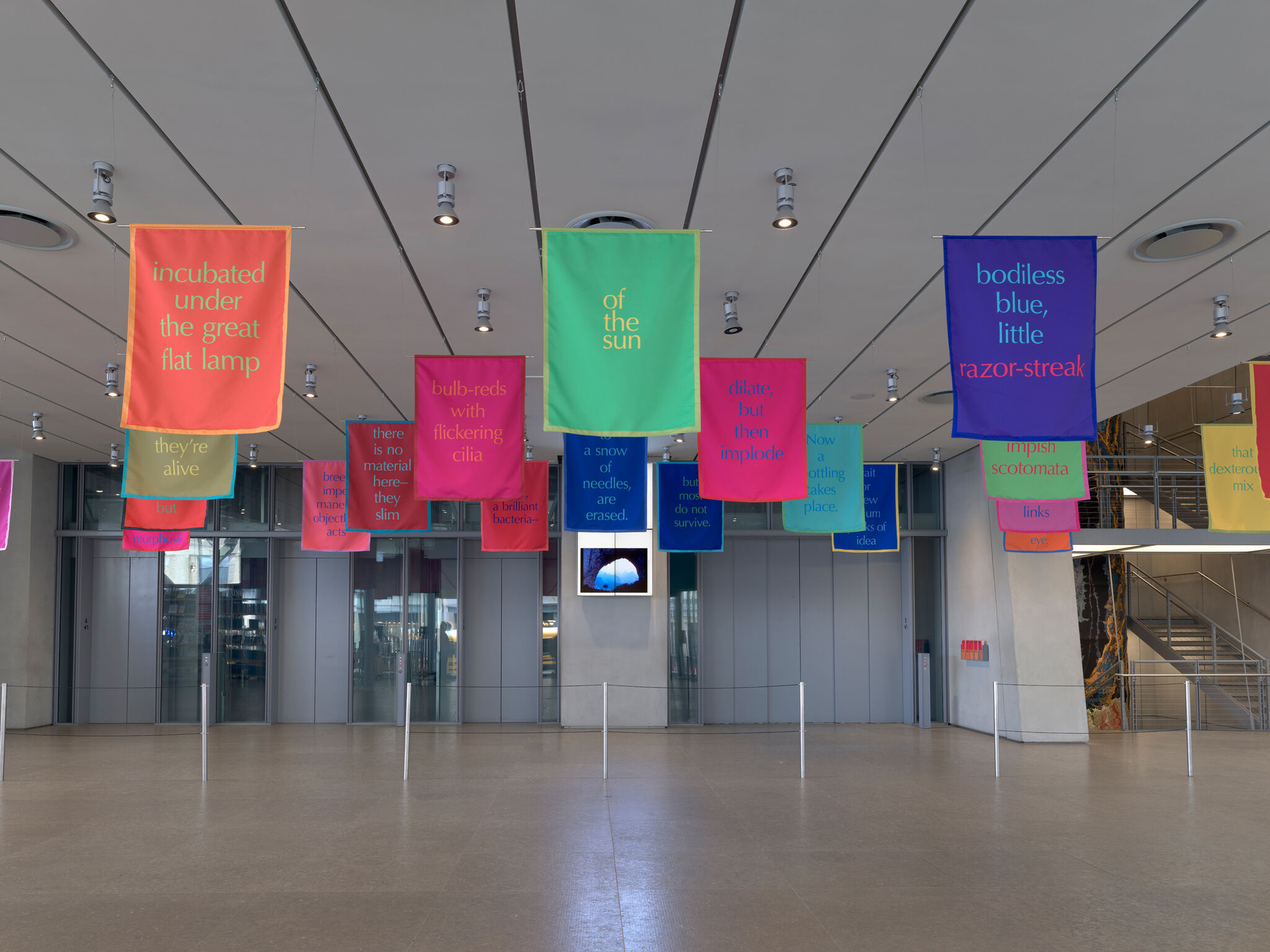

Rather than offering a unified theme, we pursue a series of hunches throughout the exhibition: that abstraction demonstrates a tremendous capacity to create, share, and sometimes withhold meaning; that research-driven conceptual art can combine the lushness of ideas and materiality; that personal narratives sifted through political, literary, and pop cultures can address larger social frameworks; that artworks can complicate the meaning of “American” by addressing the country’s physical and psychological boundaries; and that our present moment can be reimagined by engaging with under-recognized artistic models and artists we have lost. Deliberately intergenerational and interdisciplinary, this Biennial proposes that cultural, aesthetic, and political possibility begins with meaningful exchange and reciprocity.

The subtitle of this Biennial, Quiet as It’s Kept, is a colloquialism. We were inspired by the ways novelist Toni Morrison, jazz drummer Max Roach, and artist David Hammons have invoked it in their works. The phrase is typically said prior to something—often obvious—that should be kept secret. We also adorned the exhibition with a symbol, ) (, from a N. H. Pritchard poem, on view in the exhibition, as a gesture toward openness and interlude. All of the Whitney’s Biennials serve as forums for artists, and the works on view reflect their enigmas, the things that perplex them, and the important questions they are asking. But each of the Biennials also exists as an institutional statement, and every team of curators is entrusted with making an exhibition that resides within the Museum’s history, collection, and reputation. In its eightieth iteration, the Biennial continues to function as an ongoing experiment.

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It's Kept is co-organized by David Breslin, DeMartini Family Curator and Director of Curatorial Initiatives, and Adrienne Edwards, Engell Speyer Family Curator and Director of Curatorial Affairs, with Mia Matthias, Curatorial Assistant; Gabriel Almeida Baroja, Curatorial Project Assistant; and Margaret Kross, former Senior Curatorial Assistant.

Whitney Biennial 2022: Quiet as It's Kept is presented by

Generous support is provided by

Generous support is also provided by Judy Hart Angelo; The Brown Foundation, Inc., of Houston; Elaine Graham Weitzen Foundation for Fine Arts; Lise and Michael Evans; John R. Eckel, Jr. Foundation; Kevin and Rosemary McNeely, Manitou Fund; The Philip and Janice Levin Foundation; The Rosenkranz Foundation; Anne-Cecilie Engell Speyer and Robert Speyer; and the Whitney's National Committee.

Major support is provided by The Keith Haring Foundation Exhibition Fund, the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, and an anonymous donor.

Significant support is provided by 2022 Biennial Committee Co-Chairs: Jill Bikoff, Beth Rudin DeWoody, Barbara and Michael Gamson, Miyoung Lee, Bernard Lumpkin, Julie Mehretu, Fred Wilson; 2022 Biennial Committee Members: Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons, Sarah Arison and Thomas Wilhelm, Candy and Michael Barasch, James Keith (JK) Brown and Eric Diefenbach, Eleanor and Bobby Cayre, Alexandre and Lori Chemla, Suzanne and Bob Cochran, Jenny Brorsen and Richard DeMartini, Fairfax Dorn and Marc Glimcher, Stephen Dull, Martin and Rebecca Eisenberg, Melanie Shorin and Greg S. Feldman, Jeffrey & Leslie Fischer Family Foundation, Cindy and Mark Galant, Christy and Bill Gautreaux, Debra and Jeffrey Geller Family Foundation, Aline and Gregory Gooding, Janet and Paul Hobby, Harry Hu, Peter H. Kahng, Michèle Gerber Klein, Ashley Leeds and Christopher Harland, Dawn and David Lenhardt, Jason Li, Marjorie Mayrock, Stacey and Robert Morse, Daniel Nadler, Opatrny Family Foundation, Orentreich Family Foundation, Nancy and Fred Poses, Marylin Prince, Eleanor Heyman Propp, George Wells and Manfred Rantner, Martha Records and Richard Rainaldi, Katie and Amnon Rodan, Jonathan M. Rozoff, Linda and Andrew Safran, Subhadra and Rohit Sahni, Erica and Joseph Samuels, Carol and Lawrence Saper, Allison Wiener and Jeffrey Schackner, Jack Shear, Annette and Paul Smith, the Stanley and Joyce Black Family Foundation, Robert Stilin, Rob and Eric Thomas-Suwall, and Patricia Villareal and Tom Leatherbury; as well as the Alex Katz Foundation, Further Forward Foundation, the Kapadia Equity Fund, Gloria H. Spivak, and an anonymous donor.

Funding is also provided by special Biennial endowments created by Melva Bucksbaum, Emily Fisher Landau, Leonard A. Lauder, and Fern and Lenard Tessler.

Curatorial research and travel for this exhibition were funded by an endowment established by Rosina Lee Yue and Bert A. Lies, Jr., MD.

New York magazine is the exclusive media sponsor.

In the News

"After three years of soul-rattling history, this year’s survey at the Whitney Museum of American Art is reflective and adult-thinking."—The New York Times

". . . the exhibition offers a mix of styles, practices and perspectives that invite contemplation, conversation and return engagements."—Gothamist

". . . a tender, understated survey of the American art scene as it stands right now that also acts as a means of processing the grief of the last two years."—ARTnews

". . . if this Biennial doesn’t feel quite like it can let itself go fully wild, there is also a quiet weirdness to it that sincerely reflects the disorienting headspace of the present, and that is worth the trip."—Artnet News

"Delayed for a year by the pandemic, the show is exciting without being especially pleasurable—it’s geared toward thought."—The New Yorker

". . . the show feels serious and thoughtful throughout, as if dire times require us to forgo old strategies of confrontation and performative anger and get down to the hard work of understanding the world."—The Washington Post

"Revelling in difference—not just of opinion but of style, focus, and approach, it pushes for meaningful exchanges between objects and viewers alike."—Ocula

"An ambitious survey of American art that locates both hope and precarity in the mutability of the present moment."—4Columns

"The 63 artists’ works interact with one another, offering alinear, yet continuous conversation through the psyche and also the pits of our stomachs."—Flaunt

"The exhibition mimics the range of emotions we felt during the past two years, from fear and pain to joy and hope, and everything in between."—Time Out New York

". . . this year’s offering, even with the inclusion of deceased artists, radiates with the power of now."—Vulture

More from this series

Learn more about the Whitney Biennial, the longest-running survey of American art.