Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018 | Art & Artists

Sept 28, 2018–Apr 14, 2019

Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018 | Art & Artists

Rule, Instruction, Algorithm:

Ideas as Form

1

Artists have long used instructions and abstract concepts to produce their work, employing mathematical principles, creating thought diagrams, or establishing rules for variations of color. Conceptual art—a movement that began in the late 1960s—went a step further, explicitly emphasizing the idea as the driving force behind the form of the work. In his “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” (1967), Sol LeWitt wrote: “The plan would design the work. Some plans would require millions of variations, and some a limited number, but both are finite. Other plans imply infinity.” The works in this grouping—from Sol LeWitt’s large-scale wall drawing and Josef Albers’s series of nesting colored squares and rectangles to Lucinda Childs’s dances and Joan Truckenbrod’s computer drawings—all directly address the rules and instructions used in their creation. Essential to each is an underlying system that allows the artist to generate variable images and objects.

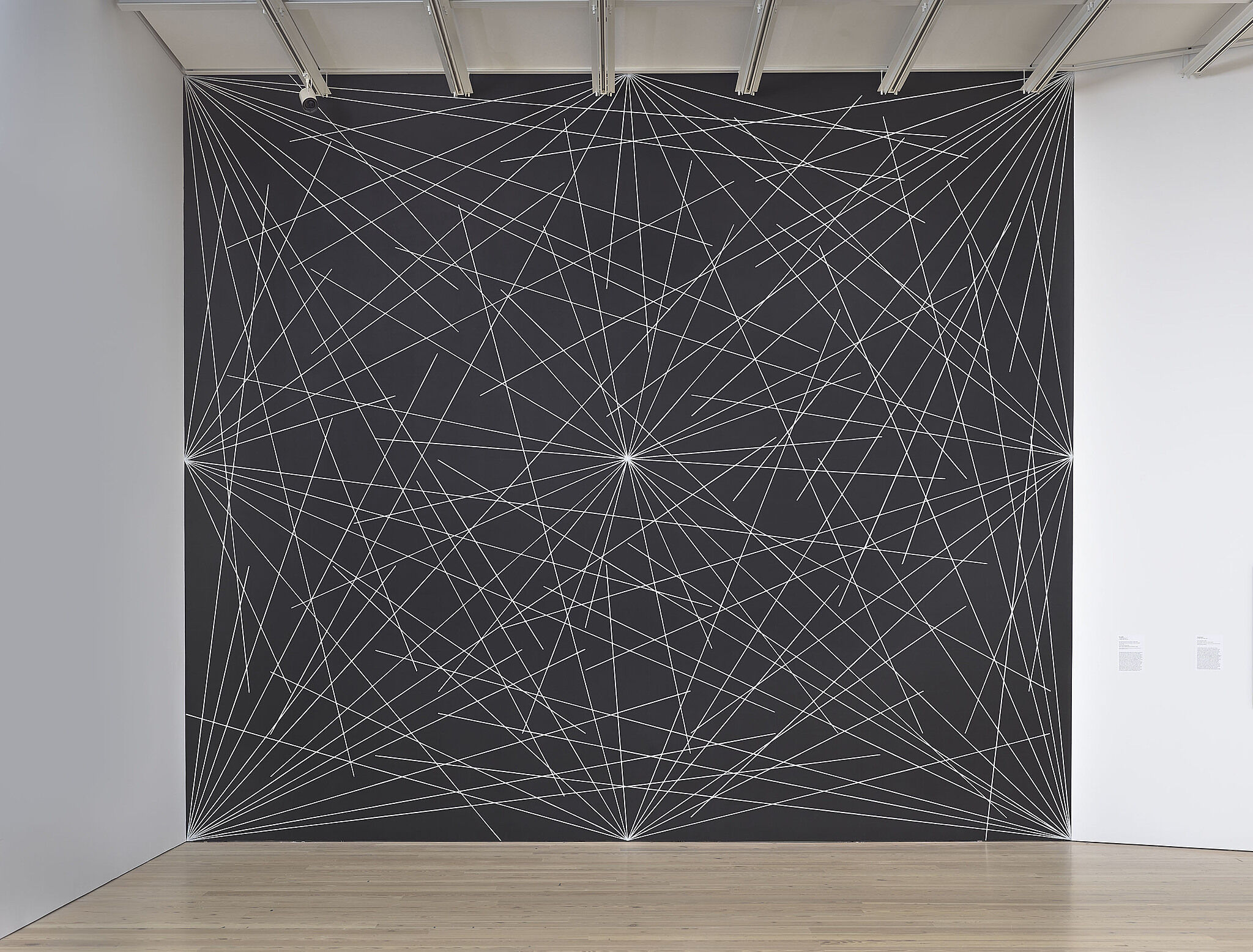

Sol LeWitt, Wall drawing #289, 1976

Encapsulating the artist’s idea that “the idea or concept is the most important aspect of the work,” Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings are actually sets of instructions that others execute when the work is to be exhibited. Wall Drawing #289, when implemented fully, covers four walls, of which only the fourth is on view here— a possibility LeWitt left open and that speaks to the work’s adaptability. The exact angle and length of the lines here—twenty-four from the center, twelve from the midpoint of each of the sides, and twelve from each corner—are determined by those who draw them, and the work may be adapted to fit a variety of architectural contexts. Consequently, the wall drawing is scalable and can differ significantly with each realization. Although it is executed by a human rather than a computer, its language-based instructions function as a program would in a digital work of art.

Artists

- Josef Albers

- Cory Arcangel

- Tauba Auerbach

- Jonah Brucker-Cohen

- Jim Campbell

- Ian Cheng

- Lucinda Childs

- Charles Csuri

- Agnes Denes

- Alex Dodge

- Charles Gaines

- Philip Glass

- Frederick Hammersley

- Channa Horwitz

- Donald Judd

- Joseph Kosuth

- Shigeko Kubota

- Marc Lafia

- Barbara Lattanzi

- Lynn Hershman Leeson

- Sol LeWitt

- Fang-yu Lin

- Manfred Mohr

- Katherine Moriwaki

- Mendi + Keith Obadike

- Nam June Paik

- William Bradford Paley

- Paul Pfeiffer

- Casey Reas

- Earl Reiback

- Rafaël Rozendaal

- Lillian Schwartz

- James L. Seawright

- John F. Simon Jr.

- Steina

- Mika Tajima

- Tamiko Thiel

- Cheyney Thompson

- Joan Truckenbrod

- Siebren Versteeg

- Lawrence Weiner