Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018 | Art & Artists

Sept 28, 2018–Apr 14, 2019

Programmed: Rules, Codes, and Choreographies in Art, 1965–2018 | Art & Artists

Rule, Instruction, Algorithm:

Ideas as Form

1

Artists have long used instructions and abstract concepts to produce their work, employing mathematical principles, creating thought diagrams, or establishing rules for variations of color. Conceptual art—a movement that began in the late 1960s—went a step further, explicitly emphasizing the idea as the driving force behind the form of the work. In his “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art” (1967), Sol LeWitt wrote: “The plan would design the work. Some plans would require millions of variations, and some a limited number, but both are finite. Other plans imply infinity.” The works in this grouping—from Sol LeWitt’s large-scale wall drawing and Josef Albers’s series of nesting colored squares and rectangles to Lucinda Childs’s dances and Joan Truckenbrod’s computer drawings—all directly address the rules and instructions used in their creation. Essential to each is an underlying system that allows the artist to generate variable images and objects.

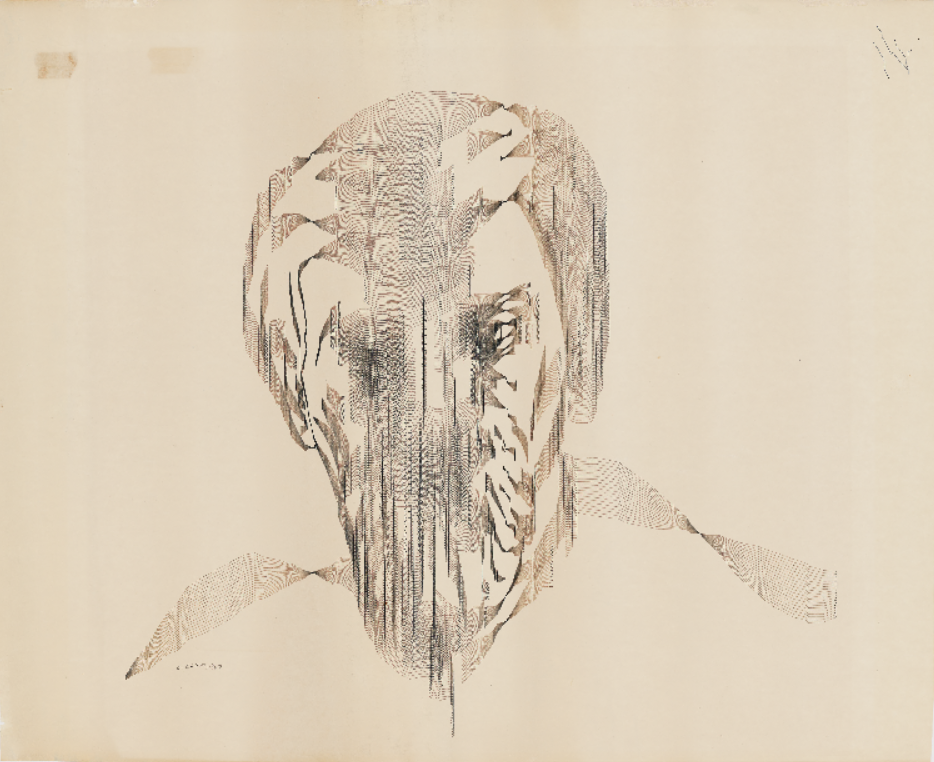

Charles Csuri, Sine Curve Man, 1967*

In 1967, Charles “Chuck” Csuri’s Sine Curve Man, created at Ohio State University in collaboration with programmer James Shaffer, stood out as one of the most complex figurative computer-generated images. As Csuri and Shaffer explained, to make the work, “a picture of a man was placed in the memory of an IBM 7094. Mathematical strategies were then applied to the original data.” Csuri and Shaffer’s code transformed the line drawing of the man by repeatedly vertically shifting an X or Y value of the given curve and letting the resulting drawings accumulate on top of each other. Csuri felt that peer artists working with technology at the time had tended to place more emphasis on materials and technical processes than the underlying scientific concepts creating those products. For Csuri, the computer brought the artist closer to the scientist, allowing him to directly work with basic scientific concepts and examine the laws creating physical reality.

*Installed as part of an earlier version of the exhibition.

Artists

- Josef Albers

- Cory Arcangel

- Tauba Auerbach

- Jonah Brucker-Cohen

- Jim Campbell

- Ian Cheng

- Lucinda Childs

- Charles Csuri

- Agnes Denes

- Alex Dodge

- Charles Gaines

- Philip Glass

- Frederick Hammersley

- Channa Horwitz

- Donald Judd

- Joseph Kosuth

- Shigeko Kubota

- Marc Lafia

- Barbara Lattanzi

- Lynn Hershman Leeson

- Sol LeWitt

- Fang-yu Lin

- Manfred Mohr

- Katherine Moriwaki

- Mendi + Keith Obadike

- Nam June Paik

- William Bradford Paley

- Paul Pfeiffer

- Casey Reas

- Earl Reiback

- Rafaël Rozendaal

- Lillian Schwartz

- James L. Seawright

- John F. Simon Jr.

- Steina

- Mika Tajima

- Tamiko Thiel

- Cheyney Thompson

- Joan Truckenbrod

- Siebren Versteeg

- Lawrence Weiner