Visual description

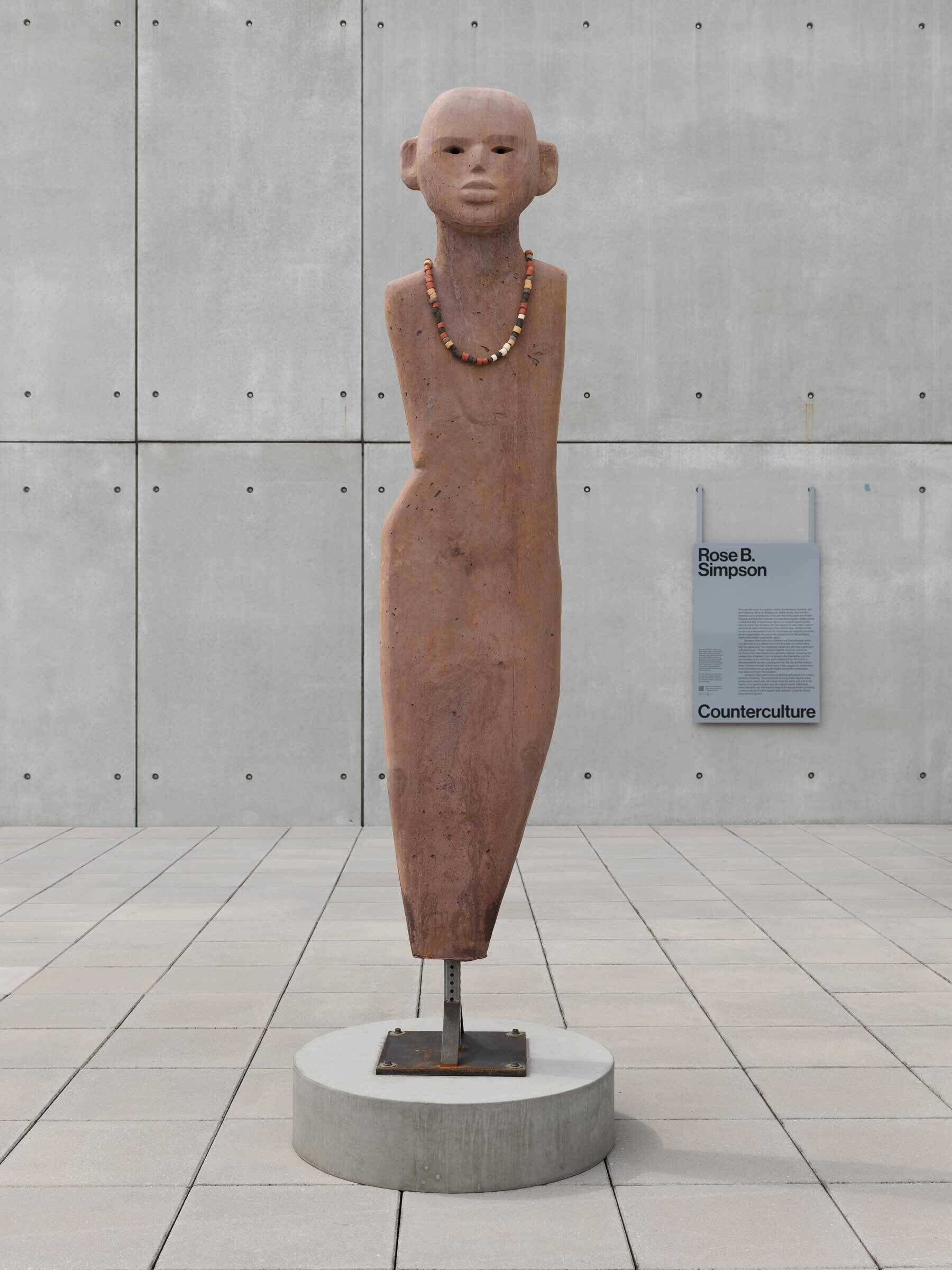

The installation of Counterculture on view at the Whitney is five of the original twelve large scale figurative works made of cast cement by Santa Clara Pueblo artist Rose B. Simpson. Each sculpture is reminiscent of the human form, but well beyond life-size, measuring over 10 feet in height, 2 feet in width and less than 1 foot in depth.

The faces of the figures are wide and round, with sculpted lips and noses protruding outward from the face. Where the eyes would be are almond shaped holes, which have been created by drilling all the way through the figures’ faces; Simpson has noted these holes allow the figure to “stand as a witness and as a voice and as a way to bring consciousness to the stories of the past and the beings of all kinds”. Each neck is adorned with a necklace of handcrafted clay beads, leading into smooth, armless torsos and legs, with no indications of any anatomy. The figures do not have any feet. Each figure has no definitive gender. Simpson said about this gender-neutral presentation:

Most of my work is a self-portrait of sorts. As someone who is Two-Spirit or has always struggled with gender and trying to understand it, I feel like my story is best told from my own bodily experience. So I'm making myself in a sense, and this is how we empathize in the world, is when we see ourselves in something else.

While the figures are cast in cement, they have each been dyed a different warm, earthy tone, inspired by the colors of the earth, ground, and dirt that the artist is surrounded by in her native Southwest, as well as the clay that she typically works with. This choice in coloring was also partially inspired by the figures’ placement on the east coast; in the Southwest, where the landscape is characterized as earthy and warm, the figures could almost disappear into the landscape. However, on the east coast, the warm, earthy tones contrast intensely with the blues and grays of the landscape and city. In addition, you may be able to note fingerprints in the clay beads, relics of birds using the sculptures as a resting place, rust, or moss across the installation. These signifiers of interaction with the landscape and the artist are encouraged by Simpson, as they push the viewer to notice “how place begins to affect everything that we're trying to control.” With Counterculture, Simpson aims to foreground our collaboration with nature, rather than our dominion over it.

Not on view

Date

2022

Classification

Sculpture

Medium

Three dyed-concrete and steel sculptures with ceramic and braided steel cable adornments

Dimensions

Dimensions variable, see individual components

Accession number

2023.124a-c

Series

Counterculture

Credit line

Purchase, with funds from the Painting and Sculpture Committee and Bridgitt and Bruce Evans

Rights and reproductions

© Rose B. Simpson

Audio

-

0:00

Descripción verbal: Counterculture, 2022

0:00

Narrator: La instalación de Counterculture en exposición en el Whitney consiste en cinco de un total de doce figuras de hormigón colado construidas por la artista Rose B. Simpson del Pueblo de Santa Clara. Cada escultura es una reminiscencia de la forma humana, pero de un tamaño mayor que el real, ya que miden poco más de tres metros de altura, sesenta centímetros de ancho y menos de treinta centímetros de profundidad.

Los rostros de las figuras son anchos y redondos, con labios esculpidos y narices sobresalientes. En el lugar donde irían los ojos, hay orificios de forma almendrada, que son perforaciones que atraviesan la cabeza de cada figura; Simpson ha dicho que estos orificios les permiten a las figuras “erguirse como testigos, ser una voz y una manera de poner sobre la mesa estas historias del pasado y de los seres de todo tipo”. Los cuellos están adornados con collares de cuentas de arcilla hechas a mano, y cada uno cae sobre torsos sin brazos y piernas lisos, sin indicio de anatomía alguna. Las figuras tampoco tienen pies. Y ninguna de las figuras tiene un género definido. Acerca de su representación de un género neutro, Simpson ha dicho que “la mayor parte de mi obra funciona como un tipo de autorretrato”. Al ser una persona que es dos espíritus o que siempre ha disputado el género y ha intentado entenderlo, siento que la mejor manera de contar mi historia es a través de mi propia experiencia corporal. Así que me estoy haciendo a mí misma, por así decirlo, y así es como empatizamos con el mundo, cuando nos vemos a nosotros mismos por medio de algo más”.

Aunque todas las figuras están hechas de hormigón colado, la superficie de cada una está teñida con un tono cálido y terrenal diferente inspirado en los colores de la tierra, los suelos y el polvo que rodean a la artista en su lugar natal, el suroeste estadounidense, como también en la arcilla con la que trabaja habitualmente. La elección de teñir las figuras con estos colores también se inspiró, en parte, en la ubicación de las figuras en la costa este; en el suroeste, donde el paisaje se caracteriza por ser de un color cálido y terrenal, las figuras podrían fundirse con el paisaje circundante. En cambio, en la costa este, los tonos cálidos y terrenales marcan un claro contraste con los azules y grises de la ciudad. Por otro lado, a lo largo de la instalación, también puede notar huellas de dedos en las cuentas de arcilla, rastros de aves que usan las esculturas como lugar de descanso, óxido o incluso musgo. Estos significantes de interacción con el paisaje y la artista son deliberados, ya que, como expresa Simpson, invitan al espectador a notar “cómo un lugar comienza a afectar todo lo que estamos intentando controlar”. Con Counterculture, Simpson busca poner en primer plano nuestra convivencia con la naturaleza, en vez de nuestro dominio sobre ella.

Descripción verbal: Counterculture, 2022

In Rose B. Simpson: Counterculture (Spanish)

-

0:00

Counterculture, 2022

0:00

Rose B. Simpson: Me llamo Rose B. Simpson y soy del Pueblo de Santa Clara al norte de Nuevo México, donde vivo y trabajo en mis tierras ancestrales junto con mi hija de seis años.

Esta exposición de Counterculture comprende cinco de un total de 12 figuras originales de gran escala que fueron construidas para ver. Están hechas de hormigón colado y adornadas con cuentas de arcilla fabricadas a mano. Una de las características más importantes de estas obras es que los ojos son perforaciones que atraviesan toda la cabeza. Están de pie como testigos de lo inanimado. Observan, nos muestran, personifican y ponen cuerpo a lo inanimado que nuestra cultura moderna olvida que nos observa constantemente.

Puede ser el mundo natural, pueden ser seres ancestrales, pueden ser sucesos sobrenaturales. Puede ser el viento, pueden ser las nubes, puede ser el clima, pueden ser las partes de nuestro mundo que no necesariamente creemos que son conscientes de nuestros movimientos o decisiones como seres posmodernos.

En las perforaciones que atraviesan la cabeza en lugar de los ojos, puede ver el paso de la luz o sentir una pequeña corriente de aire. Creo que eso es algo importante. Mientras perforaba las cabezas, volaba polvillo alrededor. En cuanto la herramienta llegó al otro lado, una brisa sopló el polvillo hacia fuera, y lo sentí como un gran momento de concesión. Llegué al otro lado, y me sentí casi interdimensional.

Quizá note huellas de dedos en las cuentas de arcilla. Quizá note marcas de animales que entraron en contacto con las piezas; quizá hubo pájaros que encontraron un lugar donde anidar o descansar. Quizá veamos óxido, veamos musgo, o veamos momentos en los que las esculturas han ocupado un lugar y crecerán en relación al lugar y se transformarán a raíz del lugar. Y creo que empezamos a notar cómo un lugar comienza a afectar todo lo que estamos intentando controlar. En cierto sentido, interactuamos con la naturaleza; no la controlamos ni controlamos nuestra relación con ella.

He estado pensando mucho acerca del empoderamiento. En mi opinión, el empoderamiento en el pasado siempre giró alrededor del hombre, y tuve que recurrir a una mentalidad de guerrero para sentirme empoderada. Y más recientemente, en especial desde que soy madre, he encontrado mucho poder en lo femenino o en aquello que es consciente de sí mismo o que enaltece su propia apariencia; ponerse un collar o tomarse el tiempo de arreglarse con gracia es, en realidad, un sentido increíble de empoderamiento.

Por lo tanto, los collares no son adornos de guerra, sino objetos de empoderamiento que despliegan una imagen de respeto propio y un momento de reflexión estética, lo que, a su vez, manifiesta un sentido de poder que he estado buscando toda mi vida. Y ansío transformar mi poder agresivo en un poder lleno de gracia.

También creo que las formas se volvieron inherentemente femeninas de cierta manera. Siento que la mayor parte de mi obra funciona como un tipo de autorretrato. Al ser una persona que es dos espíritus o que siempre ha disputado el género y ha intentado entenderlo, siento que la mejor manera de contar mi historia es a través de mi propia experiencia corporal. Así que me estoy haciendo a mí misma por así decirlo, y así es como empatizamos con el mundo, cuando nos vemos a nosotros mismos por medio de algo más. Es fácil verse en otra persona, quizá del mismo género, la misma raza o la misma comunidad, y podemos obligarnos a empatizar con algo que no se parece a nosotros, ya sea una persona, un género o incluso un árbol, un ave o un animal, ¿o quizá también patrones climáticos o algún otro elemento que es parte de nuestro mundo natural?

La capacidad de elaborar una respuesta empática creo que es la manera en que empezamos a crear comunidad y una relación con cosas que superan lo que nos enseñaron a hacer.

Cuando estoy en la ciudad de Nueva York, pienso seguido en la historia. Existen tantas capas de experiencia, de vida, de historia en un solo lugar. Se puede ver visceralmente en los edificios, que son capas y pilas concretas de historias. Pero pienso en la historia de los pueblos indígenas que alguna vez vivieron y tuvieron miles de años de historia propia, y también en todas las plantas, los animales y los paisajes que se han erradicado y han desaparecido de este lugar.

Por otro lado persiste el trauma de los pueblos esclavizados, quienes fueron utilizados para construir este país y la infraestructura de este país que ahora damos por sentado, ya sean pueblos africanos esclavizados, pueblos chinos esclavizados, pueblos indígenas esclavizados, además de las comunidades de inmigrantes de distintos países que fueron explotados y abusados. Y pienso que muchas de estas historias, a pesar de no ser honradas o comprendidas, o de que no han tenido los medios para expresarse, permanecen aquí. Todavía se cuestionan, todavía se preguntan qué sucedió y puede que todavía estén esperando la respuesta. Pienso en eso a cada lugar que voy.

Por eso creo que estas esculturas son testigos, una voz, una manera de poner sobre la mesa estas historias del pasado y de los seres de todo tipo que han existido y han sido, desde el genocidio hasta distintos modos de exterminación traumática, incluso de catástrofes ambientales. Y con respecto a la vida diaria, pienso en los pájaros que viven en la ciudad, el río que la atraviesa. Pienso en los árboles que están en estos cercos en la acera y que se elevan hacia el cielo intentando que estos edificios enormes no les quiten luz de sol. Pienso en estas historias y en cómo siguen presentes y todavía conservan un corazón para mantenerse vivas, y en cómo todos estamos relacionados, pero nos olvidamos de esta relación cuando nos movemos por el mundo, como si estuviéramos a cargo.

Counterculture, 2022

In Rose B. Simpson: Counterculture (Spanish)

-

0:00

Verbal Description: Counterculture, 2022

0:00

Narrator: The installation of Counterculture on view at the Whitney is five of the original twelve large scale figurative works made of cast cement by Santa Clara Pueblo artist Rose B. Simpson. Each sculpture is reminiscent of the human form, but well beyond life-size, measuring over 10 feet in height, 2 feet in width and less than 1 foot in depth.

The faces of the figures are wide and round, with sculpted lips and noses protruding outward from the face. Where the eyes would be are almond shaped holes, which have been created by drilling all the way through the figures’ faces; Simpson has noted these holes allow the figure to “stand as a witness and as a voice and as a way to bring consciousness to the stories of the past and the beings of all kinds”. Each neck is adorned with a necklace of handcrafted clay beads, leading into smooth, armless torsos and legs, with no indications of any anatomy. The figures do not have any feet. Each figure has no definitive gender. Simpson said about this gender-neutral presentation:

Rose B. Simpson: Most of my work is a self-portrait of sorts. As someone who is Two-Spirit or has always struggled with gender and trying to understand it, I feel like my story is best told from my own bodily experience. So I'm making myself in a sense, and this is how we empathize in the world, is when we see ourselves in something else.

Narrator: While the figures are cast in cement, they have each been dyed a different warm, earthy tone, inspired by the colors of the earth, ground, and dirt that the artist is surrounded by in her native Southwest, as well as the clay that she typically works with. This choice in coloring was also partially inspired by the figures’ placement on the east coast; in the Southwest, where the landscape is characterized as earthy and warm, the figures could almost disappear into the landscape. However, on the east coast, the warm, earthy tones contrast intensely with the blues and grays of the landscape and city. In addition, you may be able to note fingerprints in the clay beads, relics of birds using the sculptures as a resting place, rust, or moss across the installation. These signifiers of interaction with the landscape and the artist are encouraged by Simpson, as they push the viewer to notice “how place begins to affect everything that we're trying to control.” With Counterculture, Simpson aims to foreground our collaboration with nature, rather than our dominion over it.

Verbal Description: Counterculture, 2022

-

0:00

Minisode: Rose B. Simpson on Counterculture, 2022

0:00

Rose B. Simpson: My name is Rose B. Simpson, and I'm from Santa Clara Pueblo in Northern New Mexico, where I live and work on my ancestral homelands with my six-year-old daughter.

This iteration of Counterculture is five of the original twelve large-scale figurative pieces that are made to witness. They're made out of cast cement and they actually have handmade clay beads. And one of the most important features about these pieces is that they have eyes that are drilled all the way through the head. And so, they are standing as witnesses for the inanimate. They are watching, they show us, they embody, they personify the inanimate that our modern culture often forgets is constantly witnessing us.

It could be the natural world, it could be ancestral beings, it could be supernatural things. It could be the wind, it could be clouds, it could be weather, it could be the parts of our world that we don't necessarily consider conscious and aware of our movement and decisions as post-modern beings.

The holes that go through the heads where the eyes are, you might notice light coming through, you might see the wind pass through. I think that's an important thing. When I was drilling the holes through the head, the dust was blowing. As soon as the bit went through to the other side, the wind would come and the dust would blow out, and it was this incredible moment of allowing. I broke through to the other side, feeling almost inter-dimensionally.

You might notice fingerprints in the clay beads. You might notice relics of animal interaction with the pieces, maybe birds have found a place to perch or rest. We might see rust, we might see moss, we might see moments where the pieces have been in place and will grow in relationship to place and transform because of place. And I think we begin to notice how place begins to affect everything that we're trying to control. In a sense, we're in collaboration with and not in a controlling state of nature and our relationship to it.

I've been thinking a lot about empowerment. Empowerment in the past has always been very masculine centered for me, and I've looked towards a warrior mentality to feel empowered. And more recently, especially since becoming a parent, I have found a lot of power in the feminine or that which is self-aware and self-adorned, and that putting a necklace on or taking a moment to adorn oneself with grace is actually an incredible sense of empowerment.

And so, the necklaces are not warrior-making, but they're objects of empowerment and that they give a sense of self-respect and a moment of aesthetic consideration, which gives it a sense of power that I have been looking for in my life. And I look forward to transforming my power from aggression to grace.

I also think that the forms became sort of inherently feminine. And I think that most of my work is a self-portrait of sorts. As someone who is two-spirit or has always struggled with gender and trying to understand it, I feel like my story is best told from my own bodily experience. So I'm making myself in a sense, and this is how we empathize in the world, is when we see ourselves in something else. It's easy to see oneself in another person, maybe of the same gender or the same race or the same community, and can we push ourselves to begin empathizing with something that doesn't look like us, be it a person, a gender, or even something like a tree or a bird or an animal, or even weather patterns or something that's part of our natural world?

That capacity to build an empathetic response, I believe, is how we begin to build community and a relationship with things bigger than what we are taught to do.

When I'm in New York City, I think often about history. There's so many layers of experience, of life, of stories that exist in every single place. I mean, you see that so viscerally in the buildings that are actual layers and piles of stories. But I think about the history of the Indigenous peoples that once lived and had thousands of years of history in place, and also of all the plants and animals and landscape features that are now obscured and gone from this place.

There's also the trauma of communities of enslaved peoples, who were used to build this country and the infrastructure of the country that we now take for granted, that being enslaved African people, enslaved Chinese people, enslaved Indigenous people, and also the communities of migrants from different countries that have been exploited and abused. And I think a lot of those stories, when they're not honored or understood or haven't had the means to tell that story, they're still there. They're still questioning, they're still wondering what happened and they might still be watching. I think about that everywhere I go.

And so, these beings I think stand as a witness and as a voice and as a way to bring consciousness to the stories of the past and the beings of all kinds that have existed and have been from genocide to different types of traumatic extermination, even environmental catastrophe. And then to our daily life, I think about the birds that live in the city, the river that flows through. I think about the trees that have these little holes in the concrete and they reach up towards the sky trying to compete with these large buildings for sunlight. I think about their stories and how they maintain and still have this heart to be and how we're still in relationship and we forget we're in relationship when we navigate the world, like we're the ones in charge.

Minisode: Rose B. Simpson on Counterculture, 2022