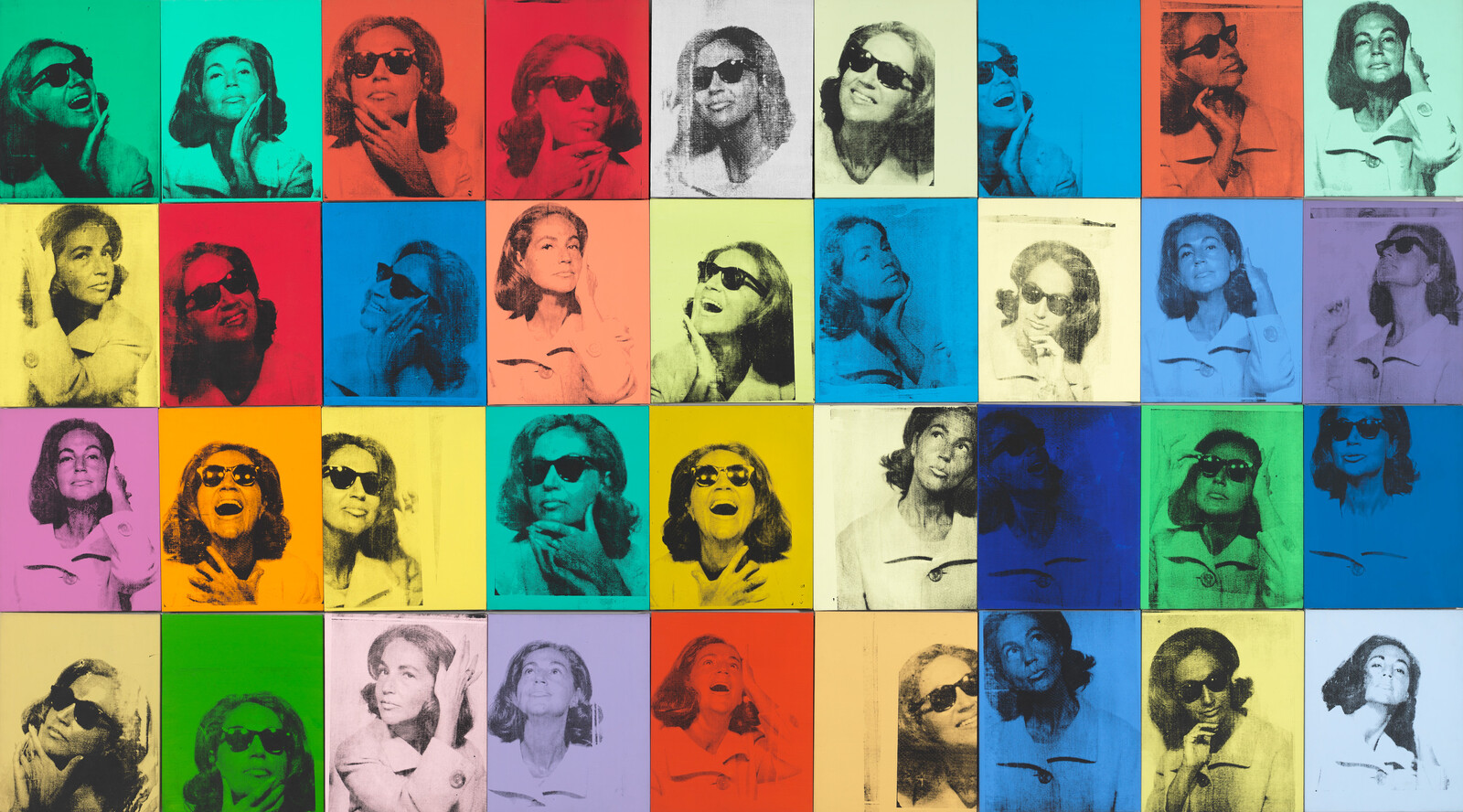

In 1964, Andy Warhol appropriated newspaper photographs of Jacqueline Kennedy for a series of dramatic paintings in which he depicted the moments before and after the assassination of her husband, President John F. Kennedy. The top row of Nine Jackies features a smiling Jackie, the President’s face barely visible to her left. This image stands in juxtaposition to the shot that appears in the painting’s middle row, taken during the ceremony in which Kennedy’s flag-draped coffin was carried to the Capitol, and to the bottom row picture, snapped as a grief-stricken Jackie stood by Lyndon B. Johnson’s side during his swearing-in ceremony. To produce this painting and the others in the series, Warhol photo-mechanically transferred the images of Jackie onto silkscreens, which were then printed onto canvas. The works combine two of his signature themes—celebrities and fatal disasters—yet these closely cropped, voyeuristic newspaper pictures differ from the glossy publicity stills that the artist typically used as the basis for his work. Now embedded in our national consciousness, the images of a bereft widow in the hours and days after her husband’s death reveal emotions that were then rarely seen in public. By using photographs from before and after the event, Warhol created a modern history painting in which the murder of a president is unseen yet tragically present.

Visual description

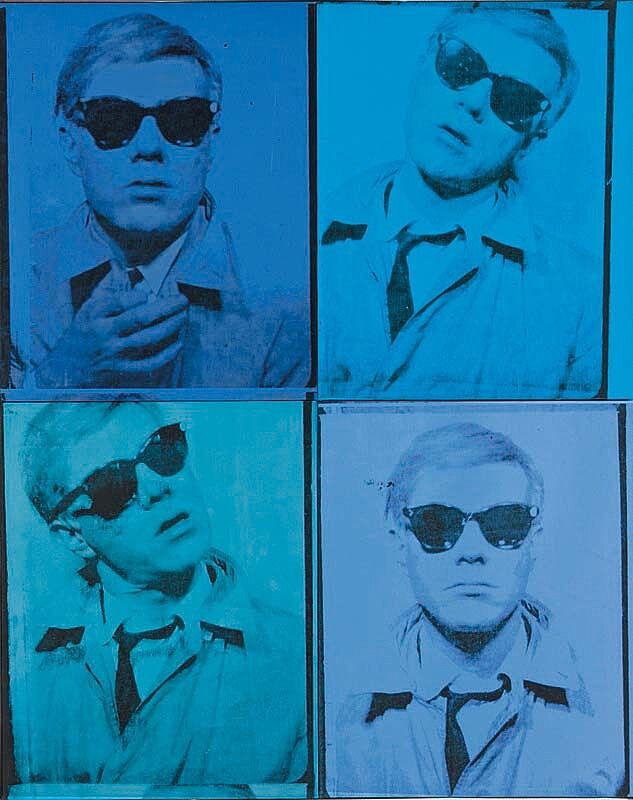

This painting, entitled Nine Jackies, was made by Andy Warhol in 1964. It examines the public persona of Jacqueline Kennedy before and after the assassination of her husband, President John F. Kennedy. To make it, Warhol pulled images of her directly from the newspaper, carefully cropping them to eliminate everything but Jackie’s image. The painting is hung vertically, measuring five feet tall by four feet wide. It is composed of nine individual screenprints on canvas, organized in three rows of three, each twenty inches tall by sixteen inches wide. Each of the rows of screenprints is a single image repeated three times, so while there are nine rectangles, there are only three different images.

The top row reveals a smiling, happy Jackie, cropped so that only her head and shoulders are visible. The image itself is made of black ink, and the background behind the images in this row is a bright, warm blue. The black ink is a bit blotchy, suggesting newsprint. Jackie looks straight into the camera, smiling broadly. She wears a small pillbox hat that tilts jauntily to the left, while her hair is bouncy and loose. Little can be seen of the background; there is a suggestion of someone standing next to her, possibly the president. This photograph was taken shortly before the assassination.

The second row of images are made up the same sketchy black ink, but the background color is a dull, somber gray. The First Lady appears in front of a man in military uniform; both gaze stoically to the right. This image comes from the president’s funeral; the figures are watching as his coffin was carried into the Capitol. The image reveals Jackie as a public figure very much controlling her emotions throughout this highly publicized ceremony.

The final row of images zooms in even closer to Jackie’s face, photographed at Lyndon B. Johnson’s swearing-in ceremony, shortly after Kennedy was pronounced dead. Once again, the image is printed in black ink, but the background color changes from rectangle to rectangle, from teal to blue and back again. Here her face appears in profile, her perfectly placed bangs obscuring her eyes. However, her hunched posture and slack mouth clearly indicate a moment of deep sadness. By juxtaposing different subtle moods Jackie displayed in the media, Warhol proposes that the viewer understand the national tragedy through the lens of her public persona.

Not on view

Date

1964

Classification

Paintings

Medium

Acrylic, oil, and screenprint on linen

Dimensions

Overall: 60 3/8 × 48 1/4 in. (153.4 × 122.6 cm)

Overall (each): 16 1/8 × 20 1/16 in. (41 × 51 cm)

Accession number

2002.273

Credit line

Gift of The American Contemporary Art Foundation, Inc., Leonard A. Lauder, President

Rights and reproductions

© The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Videos

-

Andy Warhol, Nine Jackies | Videos in American Sign Language

Audio

-

0:00

Nine Jackies, 1964

0:00

Narrator: John Hellmann es profesor de literatura inglesa en la Universidad del Estado de Ohio y autor de The Kennedy Obsession: The American Myth of J.F.K.

John Hellmann: John F. Kennedy se postuló a la presidencia en el año en que, por primera vez, según se supo, casi todos los hogares estadounidenses tenían un televisor en casa. Kennedy utilizó la fuerza de la imagen, y creo que Jackie Kennedy también la descubrió.

Narrator: Jacqueline Kennedy planeó cuidadosamente el funeral de su esposo, que fue difundido en innumerables hogares en todo el país.

John Hellmann: Un caballo negro avanzó en el funeral. No llevaba jinete para simbolizar al héroe caído. Asimismo, fue Jacqueline Kennedy quien propuso la llama eterna en la tumba de su esposo, llama que continúa ardiendo en la tumba en Washington DC.

Todos estos fueron elementos grandiosos y teatrales que dieron un significado especial y ceremonioso a la muerte de su esposo. Además, transformaron el significado de un hecho simplemente histórico y de ciencia política para insertarlo en el ámbito del arte y el mito. Considero que este es un aspecto que Andy Warhol destaca en la pintura Nine Jackies.

Nine Jackies, 1964

In Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again (Spanish)

-

0:00

Nine Jackies, 1964

0:00

Narrator: En esta pintura, Andy Warhol presenta nueve imágenes de Jacqueline Kennedy en los momentos anteriores y posteriores al asesinato de su esposo, el presidente John F. Kennedy. En la hilera superior, aparece Jacqueline Kennedy en Dallas, Texas, justo antes del asesinato. Se descubre una imagen velada del rostro de John F. Kennedy en el extremo de cada cuadro. En la hilera del centro, aparece la primera dama durante la procesión fúnebre de su esposo. En la hilera inferior, Warhol presenta un acercamiento de su rostro adolorido, tomado de una fotografía de la Sra. Kennedy de pie junto a Lyndon B. Johnson, cuando este presta juramento a bordo del Air Force One, el avión presidencial. En esta obra, Warhol destaca la manera en que los medios convirtieron a Jacqueline Kennedy en símbolo del duelo de una nación.

Warhol recortó estas imágenes de periódicos y después las pasó a serigrafía sobre lienzo. Mediante su repetición deliberada de las imágenes conmovedoras, Warhol plantea una pregunta importante: Cuando los medios nos bombardean con imágenes repetidas de una tragedia, ¿nos llevan a vivir de nuevo esos acontecimientos horrendos o nos anestesian paulatinamente frente al dolor?

Jacqueline Kennedy misma entendió la importancia de los medios y los usó de manera brillante. Para más información, por favor, continúe en la pista siguiente.

Nine Jackies, 1964

In Andy Warhol—From A to B and Back Again (Spanish)

-

0:00

Verbal Description: Nine Jackies, 1964

0:00

Narrator: This painting, entitled Nine Jackies, was made by Andy Warhol in 1964. It examines the public persona of Jacqueline Kennedy before and after the assassination of her husband, President John F. Kennedy. To make it, Warhol pulled images of her directly from the newspaper, carefully cropping them to eliminate everything but Jackie’s image. The painting is hung vertically, measuring five feet tall by four feet wide. It is composed of nine individual screenprints on canvas, organized in three rows of three, each twenty inches tall by sixteen inches wide. Each of the rows of screenprints is a single image repeated three times, so while there are nine rectangles, there are only three different images.

The top row reveals a smiling, happy Jackie, cropped so that only her head and shoulders are visible. The image itself is made of black ink, and the background behind the images in this row is a bright, warm blue. The black ink is a bit blotchy, suggesting newsprint. Jackie looks straight into the camera, smiling broadly. She wears a small pillbox hat that tilts jauntily to the left, while her hair is bouncy and loose. Little can be seen of the background; there is a suggestion of someone standing next to her, possibly the president. This photograph was taken shortly before the assassination.

The second row of images are made up the same sketchy black ink, but the background color is a dull, somber gray. The First Lady appears in front of a man in military uniform; both gaze stoically to the right. This image comes from the president’s funeral; the figures are watching as his coffin was carried into the Capitol. The image reveals Jackie as a public figure very much controlling her emotions throughout this highly publicized ceremony.

The final row of images zooms in even closer to Jackie’s face, photographed at Lyndon B. Johnson’s swearing-in ceremony, shortly after Kennedy was pronounced dead. Once again, the image is printed in black ink, but the background color changes from rectangle to rectangle, from teal to blue and back again. Here her face appears in profile, her perfectly placed bangs obscuring her eyes. However, her hunched posture and slack mouth clearly indicate a moment of deep sadness. By juxtaposing different subtle moods Jackie displayed in the media, Warhol proposes that the viewer understand the national tragedy through the lens of her public persona.

Verbal Description: Nine Jackies, 1964

-

0:00

Nine Jackies, 1964

0:00

Narrator: John Hellmann is a Professor of English at Ohio State University and the author of The Kennedy Obsession: The American Myth of J.F.K.

John Hellmann: John F. Kennedy ran for President precisely in the year where, for the first time, it was said, it was reported that virtually every American home had a television set. And he drew upon the power of film, and Jackie Kennedy I think, learned to do that as well.

Narrator: Jacqueline Kennedy carefully planned her husband’s funeral, which was broadcast into countless homes across the nation.

John Hellmann: There was a black horse in the funeral that walked along without a rider, and this was meant to symbolize the fallen hero. She also came up with the idea of the eternal flame at his grave and it still burns at his grave in Washington DC.

All these were grand, theatrical elements that gave a special, kind of ceremonious meaning to her husband’s death. And it transformed its meaning from simply history and political science into the realm of art and myth. I think that’s one of the things that Andy Warhol in the painting Nine Jackies, is drawing our attention to.

Nine Jackies, 1964

-

0:00

Nine Jackies, 1964

0:00

Narrator: In this painting, Andy Warhol presents nine images of Jacqueline Kennedy in the moments leading up to and following the assassination of her husband, President John F. Kennedy. In the top row, we see Jacqueline Kennedy in Dallas, Texas, just before the assassination. Notice the faint image of John F. Kennedy ‘s face at the edge of each frame. In the middle row, we see the First Lady during her husband’s funeral procession. And in the bottom row, Warhol presents a close-up of her grief-stricken face, taken from a photograph of Mrs. Kennedy standing next to Lyndon B. Johnson as he was sworn in aboard Air Force One. In this work, Warhol points out how the media turned Kennedy into a symbol of the grief of a nation.

Warhol took these images from newspaper photographs, which he cropped and then silkscreened onto canvas. By his deliberate repetition of the poignant images, Warhol poses an important question: When the media bombards us with repeated images of tragedy, does this make us relive and reenact these horrific events or does it gradually numb us to the pain?

Jacqueline Kennedy herself recognized the importance of the media and used it brilliantly. If you’d like to hear more, please go onto the next track.

Nine Jackies, 1964

-

0:00

Andy Warhol, Nine Jackies, 1964

0:00

Narrator: In this painting, Andy Warhol presents nine images of Jacqueline Kennedy in the moments leading up to and following the assassination of her husband, President John F. Kennedy. In the top row, we see Jacqueline Kennedy in Dallas, Texas, just before the assassination. Notice the faint image of John F. Kennedy ‘s face at the edge of each frame. In the middle row, we see the First Lady during her husband’s funeral procession. And in the bottom row, Warhol presents a close-up of her grief-stricken face, taken from a photograph of Mrs. Kennedy standing next to Lyndon B. Johnson as he was sworn in aboard Air Force One. In this work, Warhol points out how the media turned Kennedy into a symbol of the grief of a nation.

Warhol took these images from newspaper photographs, which he cropped and then silkscreened onto canvas. By his deliberate repetition of the poignant images, Warhol poses an important question: When the media bombards us with repeated images of tragedy, does this make us relive and reenact these horrific events or does it gradually numb us to the pain?

Jacqueline Kennedy herself recognized the importance of the media and used it brilliantly. To hear how, tap your screen.

Andy Warhol, Nine Jackies, 1964

-

0:00

Andy Warhol, Nine Jackies, 1964

0:00

Narrator: John Hellmann is a Professor of English at Ohio State University and the author of The Kennedy Obsession: The American Myth of J.F.K.

John Hellmann: John F. Kennedy ran for President precisely in the year where, for the first time, it was said, it was reported that virtually every American home had a television set. And he drew upon the power of film, and Jackie Kennedy I think, learned to do that as well.

Narrator: Jacqueline Kennedy carefully planned her husband’s funeral, which was broadcast into countless homes across the nation.

John Hellmann: There was a black horse in the funeral that walked along without a rider, and this was meant to symbolize the fallen hero. She also came up with the idea of the eternal flame at his grave and it still burns at his grave in Washington DC. All these were grand, theatrical elements that gave a special, kind of ceremonious meaning to her husband’s death. And it transformed its meaning from simply history and political science into the realm of art and myth. I think that’s one of the things that Andy Warhol in the painting Nine Jackies, is drawing our attention to.

Andy Warhol, Nine Jackies, 1964

Exhibitions

-

Andy Warhol—

From A to B and

Back AgainNov 12, 2018–Mar 31, 2019

-

Human Interest: Portraits from the Whitney’s Collection

Apr 2, 2016–Apr 2, 2017

-

Sinister Pop

Nov 15, 2012–Mar 31, 2013

-

Artists Making Photographs: Chamberlain, Rauschenberg, Ruscha, Samaras, Warhol

Jan 16–May 17, 2009

-

The Whitney’s Collection

Jan 30, 2008–Jan 3, 2010

-

Full House: Views of the Whitney’s Collection at 75

June 29–Sept 3, 2006

-

Pop/Concept: Highlights from the Permanent Collection

July 1–Oct 24, 2004

-

An American Legacy, A Gift to New York

Oct 24, 2002–Jan 26, 2003

-

De Kooning to Today: Highlights from the Permanent Collection (2nd floor–Oct 2002)

Oct 10, 2002–Mar 2, 2003

Installation photography

-

Installation view of Andy Warhol – From A to B and Back Again (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, November 12, 2018–March 31, 2019). From left to right: Orange Car Crash Fourteen Times, 1963; Nine Jackies, 1964; Saturday Disaster, 1964; Lavender Disaster, 1963. Photograph by Ron Amstutz. © 2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

From the exhibition Andy Warhol—

From A to B and

Back Again -

Installation view of Andy Warhol – From A to B and Back Again (Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, November 12, 2018–March 31, 2019). From left to right: Orange Car Crash Fourteen Times, 1963; Crowd, 1963; Nine Jackies, 1964; Saturday Disaster, 1964. Photograph by Ron Amstutz. © 2018 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

From the exhibition Andy Warhol—

From A to B and

Back Again