Laura Owens

1970–

Since she began painting in the early 1990s, Laura Owens has had a profound interest in texture and unconventional subject matter. Working with found objects, images, and advertisements, she frequently incorporates figurative elements into otherwise abstract compositions, pushing the boundaries of gesture, surface, and layering. Such efforts often lead her to experiment with “unfamiliar formats” as seen in her recent use of digital processes. Owens has said of her expansive approach: “Painting does things, and why wouldn’t you use all the things it does?”

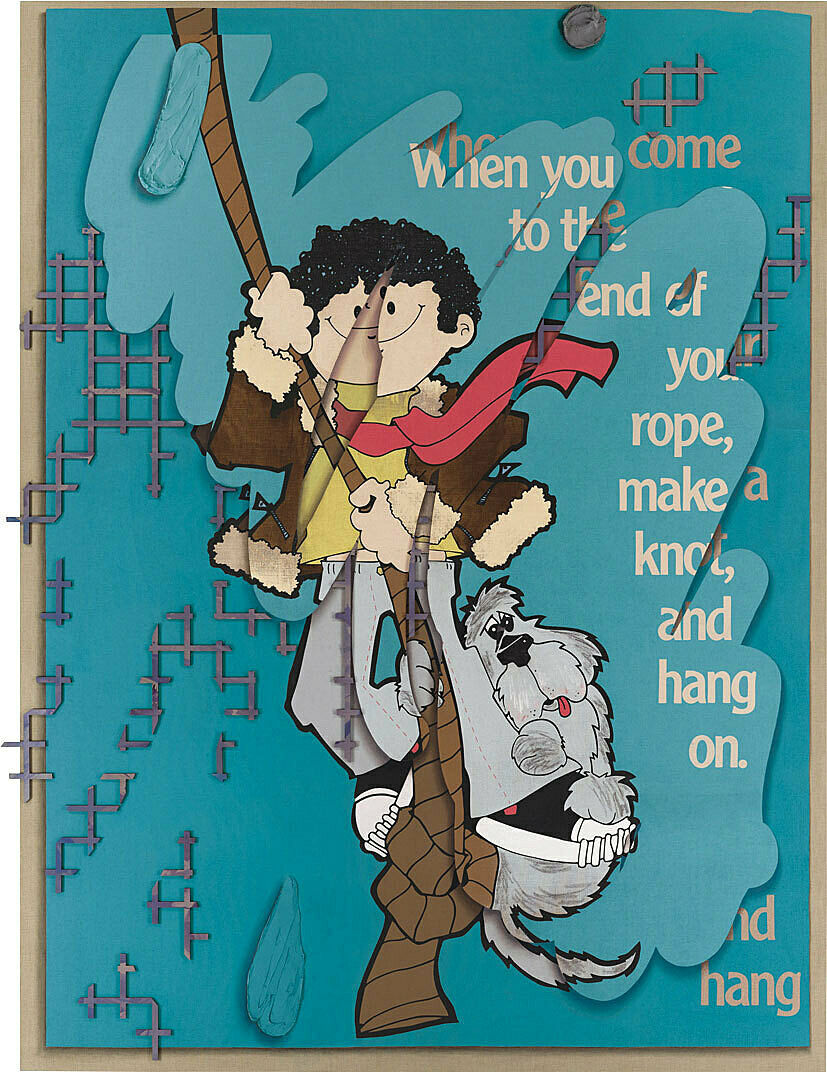

Untitled features digitally manipulated elements borrowed from a 1970s inspirational poster—including cartoonlike images of a boy and a dog along with the phrase: “When you come to the end of your rope, make a knot, and hang on.” Superimposed on the canvas and extending beyond its perimeter is a wood lattice that appears in fragments, as if partially erased. Installed on the wall behind the painting are a book and three additional, smaller paintings. Untitled can be shown as it is here with four of the works concealed or all five elements can be presented individually to form a small exhibition. By incorporating hidden elements that are integral to the work, Owens confounds what she calls the “idea of painting within a painting that runs throughout the history of art.”