Artist Njideka Akunyili Crosby On Her Billboard Project, Before Now After

May 27, 2016

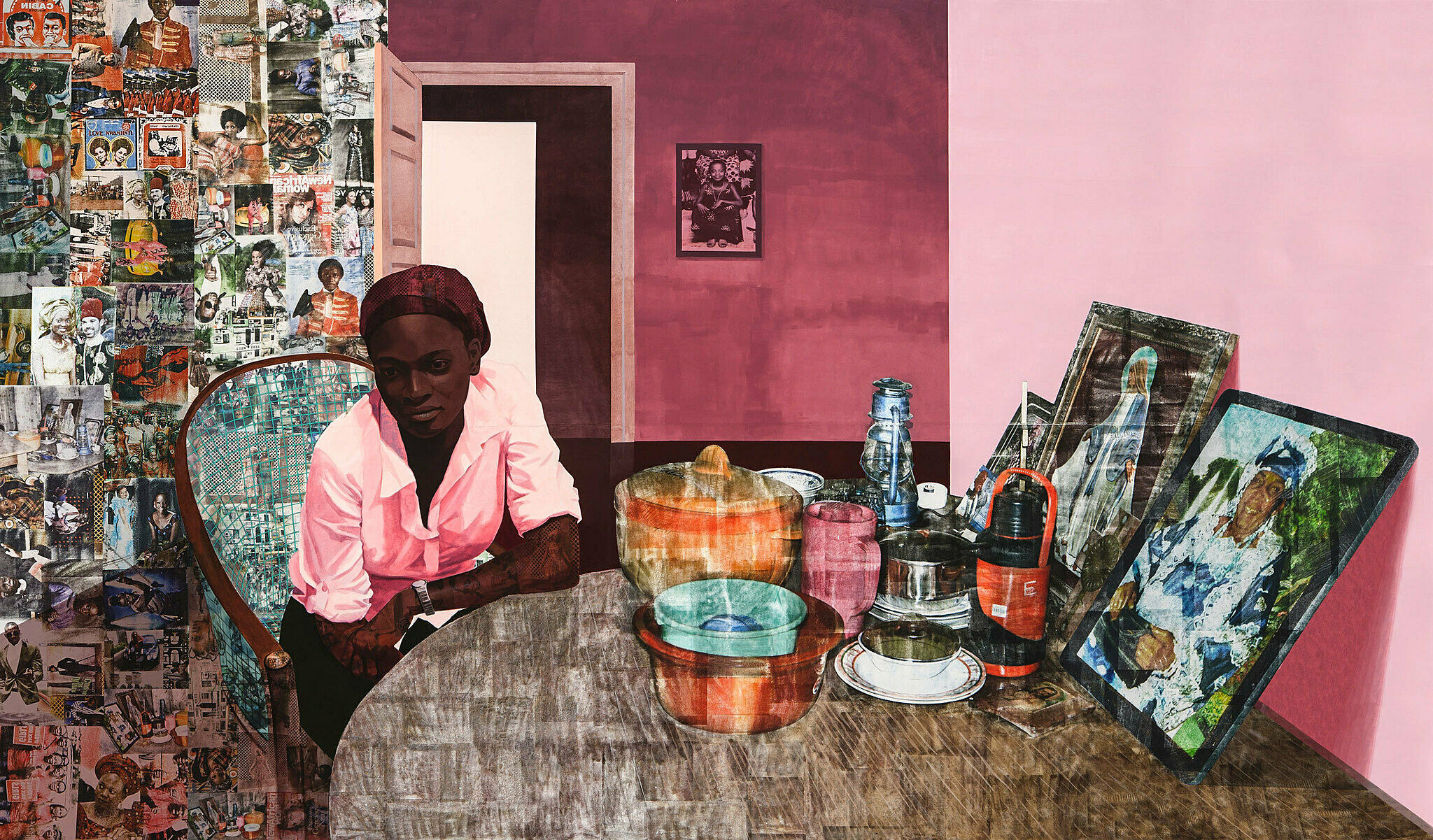

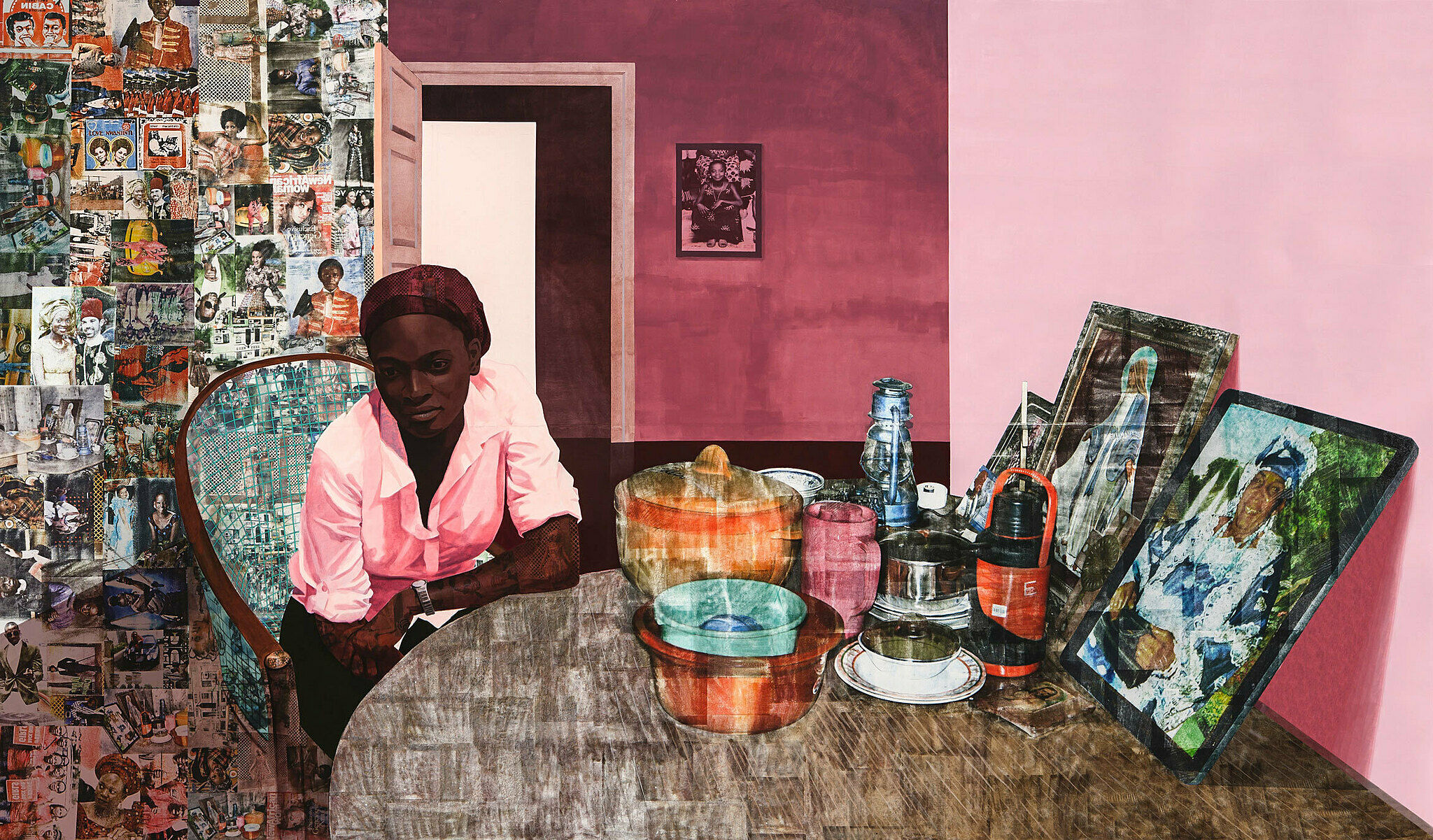

On a billboard across the street from the Whitney, Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s sister looks down toward the southern entrance of the High Line. The seven-by-eleven foot portrait is the third in a series of billboard projects that will be displayed on the facade of 95 Horatio Street over the next five years. For this display, which ends its six-month run on June 6, Crosby increased the scale of her 2014 painting Mama, Mummy and Mamma. In conversation with associate curator Jane Panetta, Crosby discusses the challenge and promise of adapting an intimate portrait to a public site, and reflects on what it means to be an American artist.

Jane Panetta: Will you talk a little bit about how we selected Mama, Mummy and Mamma for the billboard, and how you modified the work to suit the site?

Njideka Akunyili Crosby: When I got the exciting invitation to be part of the billboard series, I looked for something that fit the format. I had three works that were candidates, and Mama, Mummy and Mamma was my favorite. To make it fit the billboard I decided to extend each side instead of just stretching it out, which would make the image wonky.

Once I decided I had to extend it; the next question was how to extend it. I use Photoshop in my practice as a drawing tool, but all I know how to do is to select an area and flip through color options. I tried to do it by myself and it was horrible, but then I realized I live in Los Angeles—in the middle of Hollywood. I thought if a movie like Avatar can exist, then someone in this town can extend this painting and make it look seamless. So I talked to a few people and found this lovely guy Max, who is very well versed in Photoshop and digital technology. We went back and forth, and he was able to do it perfectly.

Everything you see [to the left of] the chair was digitally grafted to extend the painting. My grandmother is [pictured in] the very last frame on the right side of the table, wearing a blue and white lace dress. Her face and everything else you see to the right of it is added on. Max couldn’t just copy the photograph of my grandmother; it had to look like it was transferred, and it was, from another painting called The Twain Shall Meet. Max was able to reference my other work, cut out the transferred remainder of my grandmother’s face and the frame, and digitally seam it onto Mama, Mummy and Mamma. He painted in Photoshop with a lot of input from me to get the same tactility and paint quality that I get when I paint. I knew what I wanted to do, and Max had the skillset to do it, so it was a really nice back-and-forth. I consider this a different work from the original, which is why the title is Before Now After, which is after Mama, Mummy and Mamma.

JP: Who are the different figures in the painting?

NAC: The title of the original image is Mama, Mummy and Mamma. Mama was my grandmother, my father’s mother. Mummy is my mother, whose photograph is on the wall, in the back; it’s a photograph from when she was a child. The girl sitting down is my younger sister, who we all call Mamma. It’s a work about the three generations in my family, but also three generations of women. The title of the extended piece is Before Now After, extending this theme of time and generations.

The objects on the table are from my grandmother’s house in the village. I have very strong memories of the house from when I was young, because I used to spend my summers with her. There was no electricity and nothing to do for fun; at six o’clock everyone had gone to sleep. Of course, I was miserable, but as I grew older, I realized it was good. Nigerians call it training, or discipline.

When my grandmother died, the house was locked up. I have all of these memories of the house that I wanted to use, so I [went] back into the house to take pictures. She had couches with crocheted, lace patterns on the couch arm, which I’ve used before. The table was still set up as it was when she was living. I’ve been working with those pictures for a couple of years now, and at this point, they’re functioning as a stand-in for my grandmother, but also as a stand-in for that life in the village I experienced for some summers when I was young.

JP: Tell us about the composition of the scene, and how it relates to the site of the billboard at the end of the High Line?

NAC: I thought this was a good choice for the space at 95 Horatio Street because when you’re up on the High Line, you’re at eye-level with the objects on the table. You really get drawn in by the round table, which extends out into the space and implicates you. It’s a work that’s really welcoming if you think of the lines of the piece: the rounded edge of the table on the left-hand side and the lines at the bottom of the frame on the right-hand side are like a converging line.

The way you are drawn into the piece refers to someone, an artist I love and I look at fairly often: Vilhelm Hammershøi, the Scandinavian painter. A lot of his works are based on domestic spaces that are very intimate. The background with the dark, white-ish burgundy wall, and the open doorframe with another space opening to it—these compositional devices that invite you deeper into a space are something I borrowed from a Hammershøi painting.

JP: Do you think of yourself as an American artist? What is your relationship to American art as you see it?

NAC: I see myself as an American artist and simultaneously as a Nigerian artist. I carry both mantles at the same time. American art is so varied and kaleidoscopic that it really isn’t any one particular thing. [Thinking of this] country as an immigrant space ties to what I do in my work.

Also, all of my painting training happened in the United States. My first painting class was at the Community College of Philadelphia. When I think of the people who heavily influenced my work in my years of learning painting in the United States, a number of them are American artists, and also iconic. When I was at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, I studied with the Philadelphia based artist Sidney Goodman. You can see nods to Kerry James Marshall in my work, as well as people I studied with at Yale: Catherine Murphy, a beautiful painter who makes representational works that speak to abstraction at the same time, and one of my mentors in grad school, Mickalene Thomas. I’ve also been influenced by Alex Katz, who did the first billboard project [in this series].

JP: I like the playfulness of this being on a residential building. The domesticity of this space seemed like a good fit for the site. At the same time, the High Line is a public place; how did it feel to position this work on such a large scale, in public?

NAC: It’s so exciting for me to have a chance to present my work on a billboard at this scale. One fear I had was that the work might not translate in this format; if you see the works in real life, [there are] subtle shifts in texture from the transfers to the painted areas, [depending on] whether [paint is] rolled on or applied with a brush, or whether I mixed graphite, crushed steel, or crushed marble into the paint. All these alterations create different textures, so you move across the piece in a very slow way when you come up close to it. Even if just a little bit of that is lost, I think what makes the billboard project so successful is the scale; when you stand on the High Line looking out on this work, it expands beyond your periphery. You do end up taking that slow, deliberate journey through it that I’m excited by.

The reach of it is [also] something that’s very important for me, because I’m talking about a life I experienced in Nigeria that people don’t really know about here. People don’t really talk about cosmopolitan Nigeria, or village life. One of my early works is titled I Refuse to be Invisible. The title really came from feeling like I wasn’t being seen in this culture, and also [like I was] standing in for my experiences, or my country, as I knew it. I hold a quote by George Gerbner dear to my heart; he said that “representation in the fictional world signifies social existence; absence means symbolic annihilation.”1 Issues of representation matter. To have this work in such a public, visible place is everything I could ever dream of.

1. George Gerbner, “Violence in Television Drama: Trends and Symbolic Functions,” in Television and Social Behavior, Vol. 1, Content and Control, edited by G. A. Comstock and E. Rubinstein, 28-187 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1972).