Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables | Art & Artists

Mar 2–June 10, 2018

Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables | Art & Artists

Late Work

8

By 1935, Grant Wood began to streamline his landscape style, replacing the ornamental frills and mannerisms of his earlier work with broad, reductive shapes. He retained this stylistic simplification as he shifted to more patriotic subject matter in response to his worry that America had lost its will to defend itself against fascism, which was on the rise in Europe. He envisioned a series of paintings of American folktales, beginning with Parson Weems’s fictional account of George Washington as a child confessing to having chopped down his father’s cherry tree.

Faced with Nazi victories over the Allies in the first years of World War II, Wood turned his attention to depicting what he called the “simple, everyday things that make life significant to the average person” in order to awaken the country to what it stood to lose. He completed only two works in this second series—Spring in the Country and Spring in Town—before his death from pancreatic cancer on February 2, 1942, two hours before he would have turned fifty-one.

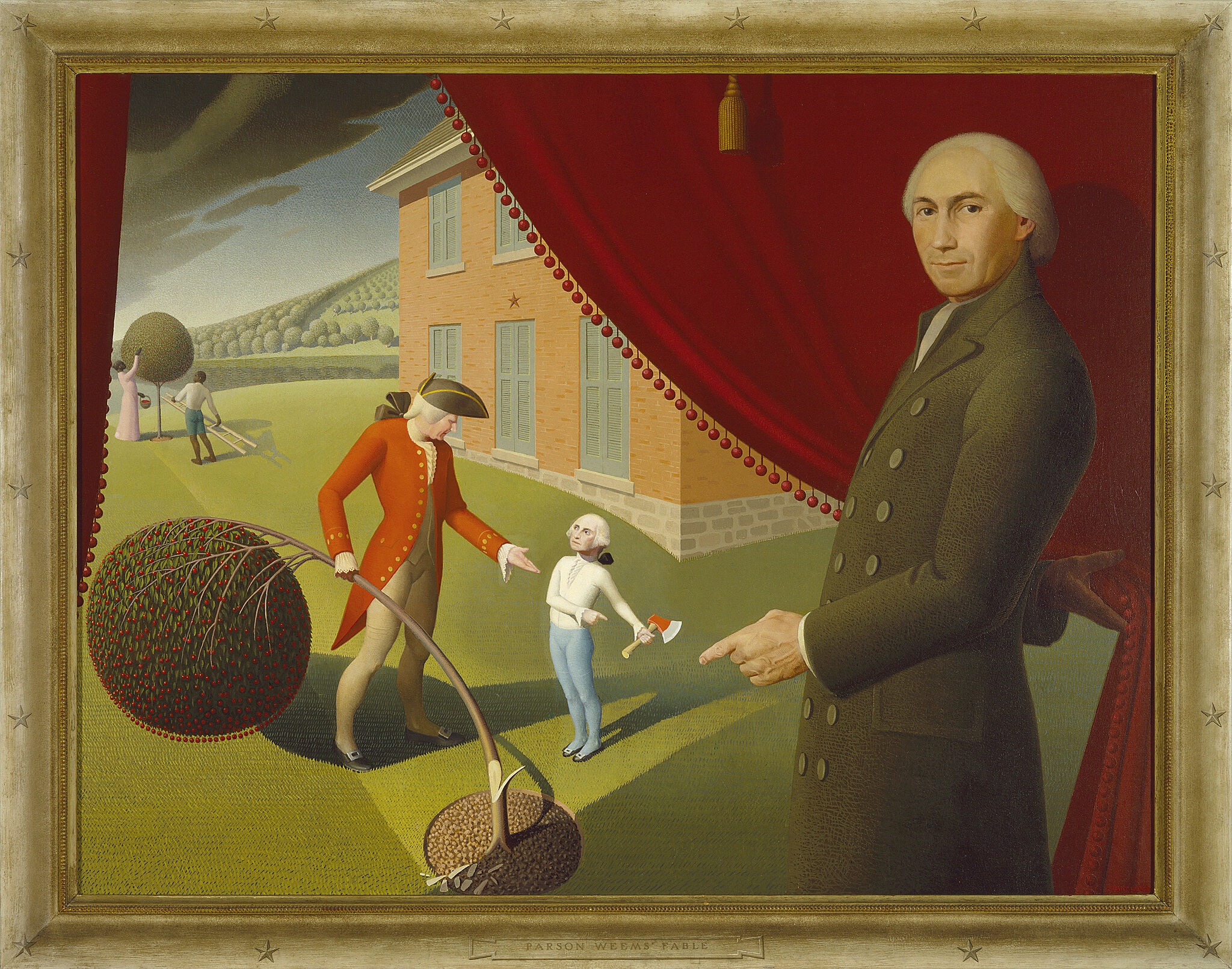

Parson Weems’ Fable, 1939

Wood intended this painting, which depicts Parson (Mason Locke) Weems’s 1806 fable of a young George Washington virtuously confessing to having cut down his father’s cherry tree, to inspire national pride. Setting up the image like a stage play, Wood portrayed Weems standing in the foreground, lifting a curtain to reveal the drama of the future president’s admission of guilt. By showing the story as fiction, Wood aimed to avoid the patriotic excess associated with fascist exploitation of national mythologies. Despite Wood’s optimistic intentions, the painting’s effect is unsettling. This feeling may arise in part from his depiction of a stern father admonishing a young Washington with the adult president’s head—an expression, perhaps, of his own powerful and occasionally conflicted memories of childhood.

From today’s perspective, the two black figures picking cherries in the background of a painting about Washington—who, like his father, was a slaveholder—serve as a reminder of slavery’s role in the making of the United States. Their presence undercuts the feeling of pride in the nation that the artist had hoped to elicit when he painted it in 1939.