David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night

July 13–Sept 30, 2018

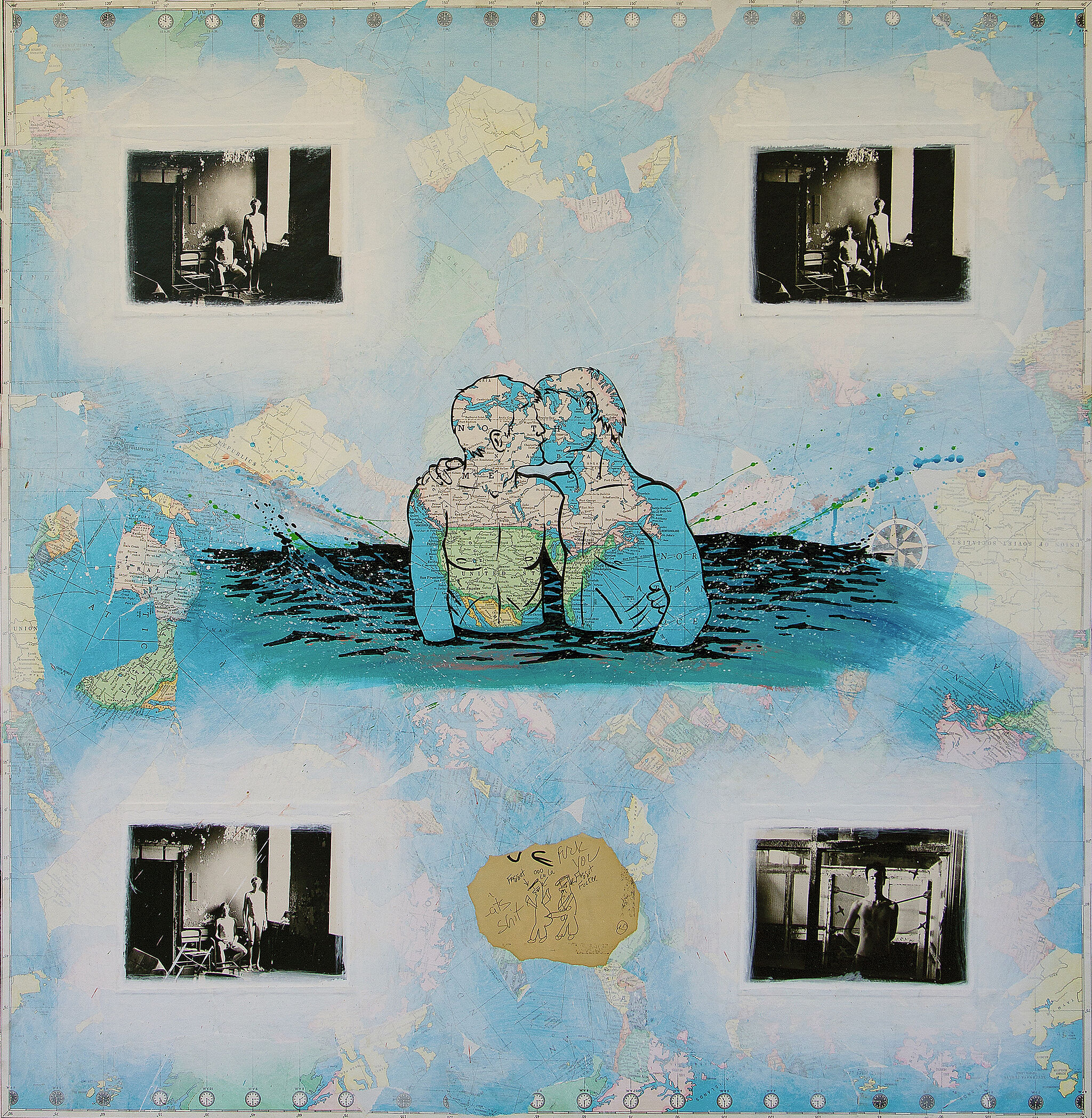

Beginning in the late 1970s, David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992) created a body of work that spanned photography, painting, music, film, sculpture, writing, and activism. Largely self-taught, he came to prominence in New York in the 1980s, a period marked by creative energy, financial precariousness, and profound cultural changes. Intersecting movements—graffiti, new and no wave music, conceptual photography, performance, and neo-expressionist painting—made New York a laboratory for innovation. Wojnarowicz refused a signature style, adopting a wide variety of techniques with an attitude of radical possibility. Distrustful of inherited structures—a feeling amplified by the resurgence of conservative politics—he varied his repertoire to better infiltrate the prevailing culture.

Wojnarowicz saw the outsider as his true subject. Queer and later diagnosed as HIV-positive, he became an impassioned advocate for people with AIDS when an inconceivable number of friends, lovers, and strangers were dying due to government inaction. Wojnarowicz’s work documents and illuminates a desperate period of American history: that of the AIDS crisis and culture wars of the late 1980s and early 1990s. But his rightful place is also among the raging and haunting iconoclastic voices, from Walt Whitman to William S. Burroughs, who explore American myths, their perpetuation, their repercussions, and their violence. Like theirs, his work deals directly with the timeless subjects of sex, spirituality, love, and loss. Wojnarowicz, who was thirty-seven when he died from AIDS-related complications, wrote: “To make the private into something public is an action that has terrific ramifications.”

This exhibition is co-curated by David Kiehl, Curator Emeritus, and David Breslin, DeMartini Family Curator and Director of the Collection.

Major Support for David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night is provided by the Ford Foundation; The Thompson Family Foundation, Inc.; and The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts.

Significant support is provided by The Keith Haring Foundation Exhibition Fund, Brooke and Daniel Neidich, the Trellis Fund, and the Whitney’s National Committee.

Generous support is provided by Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons, Susan and John Hess, Nancy and Fred Poses, The Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation, and Fern and Lenard Tessler.

Additional support is provided by James E. Cottrell and Joseph F. Lovett, the Daniel W. Dietrich II Foundation, and Gregory R. Miller and Michael Wiener.

Exhibition Catalogue

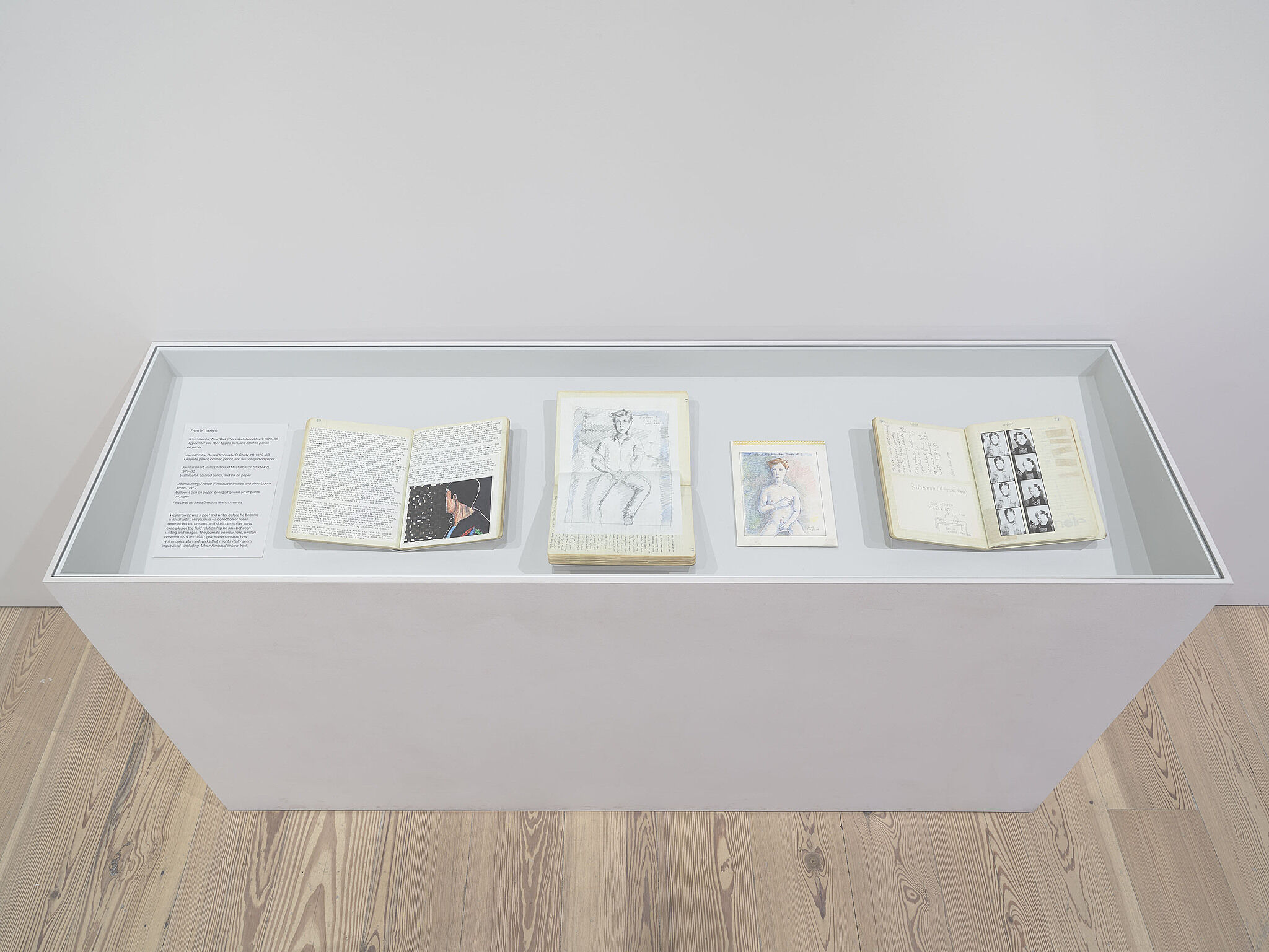

This richly illustrated book—the most definitive source on Wojnarowicz to date—is the first to comprehensively examine the artist’s life and work, pushing beyond the biographical focus that has characterized much previous scholarship. The excerpt featured here includes a selection from David Breslin’s overview essay as well as a preview of the plate section, which includes close examinations of groups of works by David Kiehl.

Gallery 11

11

Wojnarowicz’s work concerns itself with the mechanisms, politics, and manipulations of power that make some lives visible and others not. The will to make bodies present—the compulsion to clear a space for queer representations not commonly seen through language and image—was threaded throughout his work, exacerbated by the AIDS crisis, and crystallized in his work. Untitled (One Day This Kid . . . ) (1990–91) is perhaps Wojnarowicz’s best-known work. Black script shapes the boundary of a boy’s body—a boy whom we know, with his high forehead, prominent teeth, and electric eyes, is Wojnarowicz as a child. He sits for what we assume is a school picture, and he’s no older than eight. The text that surrounds him projects the child into a future scarred by abuse and homophobia. This artwork, like many by Wojnarowicz, has rightly come to embody the spirit of protest, struggle, and resistance. Wojnarowicz died on July 22, 1992. By the end of that year, 38,044 others in New York had died from AIDS-related complications. In his essay “Postcards from America: X Rays from Hell,” Wojnarowicz states what is equally true of art and protest: “With enough gestures we can deafen the satellites and lift the curtains surrounding the control room.”

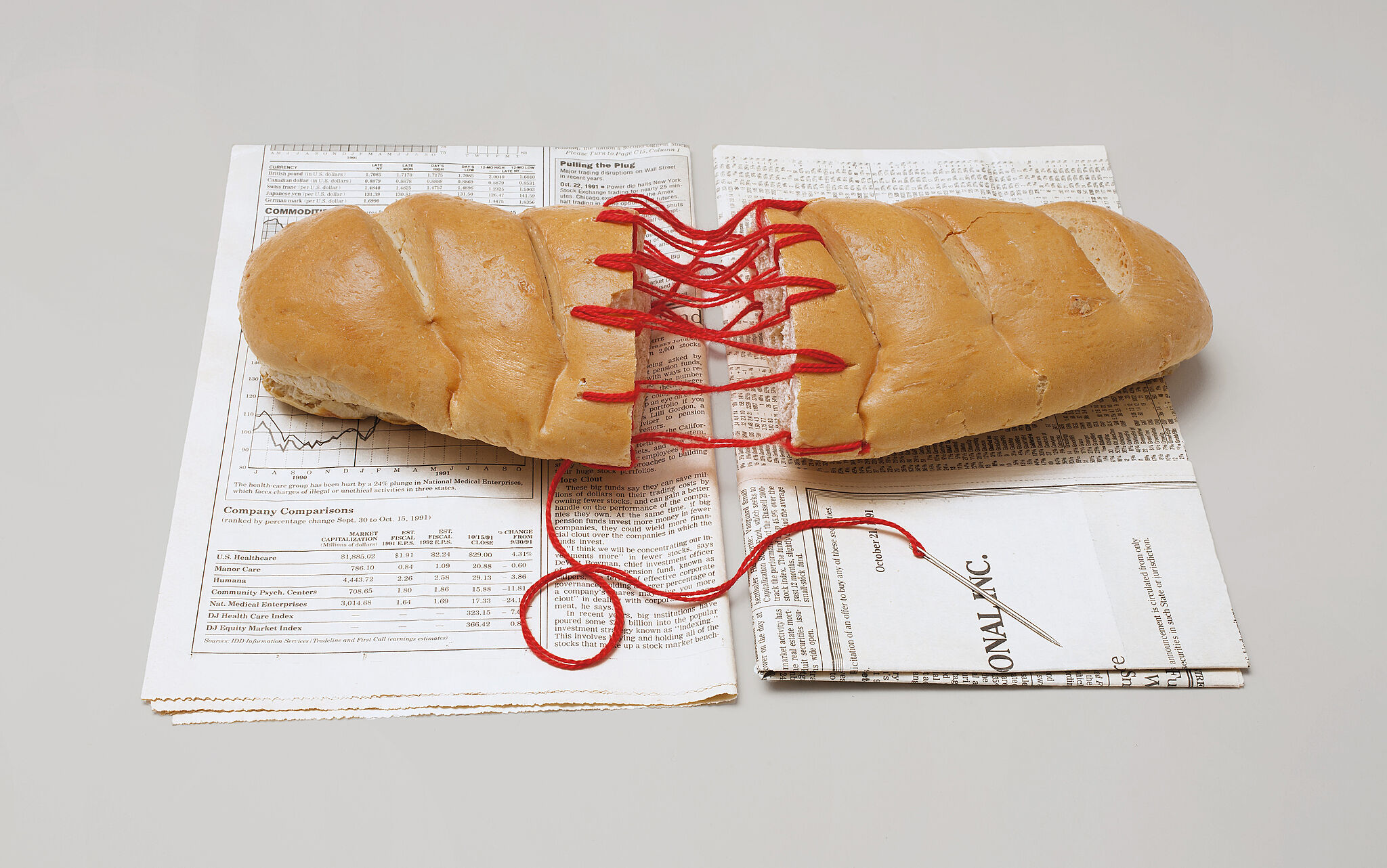

David Wojnarowicz (1954–1992), Bread Sculpture, 1988–89

Wojnarowicz used red string as a material throughout his practice. From his early supermarket posters to the flower paintings, he stitched red string into the surface of his compositions to suggest the seams and irreconcilable breaks in culture. In his unfinished film A Fire in My Belly (1986–87), Wojnarowicz included footage of the stitching together of a broken loaf of bread. This sculpture is a physical manifestation of that earlier idea. The film also included footage of what appeared to be a man’s lips being sewn together. A version of that image by Andreas Sterzing—picturing Wojnarowicz himself—would become one of the most galvanizing images to come out of the AIDS crisis.

Events

View all-

Reception and Talk: Remapping the Pre-Invented World

Saturday, September 29, 2018

1–2:30 pm -

Weekend Early Admission for Members

Repeats

Saturday, September 29, 2018

10–10:30 am -

Forever in Transition: Reconsidering Art and Politics of the 1980s

Friday, September 28, 2018

6:30 pm -

Member Night

Wednesday, September 26, 2018

7:30–10 pm

Perspectives

Mobile guides

Learn more about selected works from artists and curators.

View guide

Explore works from this exhibition

in the Whitney's collection

View 32 works

In the News

“There is a sense that he was working against time to depict the humanity of AIDS victims, to show the meaning of his own suffering to a country that didn’t seem to care.”

—The New Yorker

“The current showcasing of Wojnarowicz’s work, however, isn’t about an artist whose work has been isolated in time, so much as it’s about an artist whose voice, artwork, and thinking have transcended time.”

—The Quietus

“At a retrospective at the Whitney Museum, the life and work of the artist and AIDS activist are a model for making art out of political anger.”

—The New York Times

"A terrifyingly timely retrospective from one of the most articulate voices to emerge from the AIDS crisis.”

—Them

“David Wojnarowicz was there when we needed him politically 30-plus years ago. Now we need him again, and he’s back in a big, rich retrospective.”

—The New York Times

“It is an astonishingly relevant, urgently important retrospective. Miss it, and you miss transcendental levels of incredulity, indignation, vulnerability, lamentation, fighting back — ultimately, what it means to be human in a time of encroaching political darkness.”

—Vulture

“The retrospective, as many have noted, could not be more timely, arriving in a charged political moment not unlike the one from which Wojnarowicz emerged as a voice of searing honesty.”

—The Guardian

“A retrospective of an artists’ artist displays the wrathful gorgeousness of queer art as AIDS approached.”

—Garage

“The show discovers the qualities that make his work universal and meaningful in any age where hate, fear, and ignorance jostle with understanding and acceptance.”

—The Art Newspaper

“The retrospective allows us to finally glimpse Wojnarowicz whole; it is a must-see event for anyone who believes in the necessity of love, empathy, and moral rightness.”

—WNYC

“Rarely has an artist’s life been as intricately entwined with the objects on view — a visual life story.”

—The Village Voice

“’David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night’ gathers works spanning fourteen years of a short but prolific career, and crafts a compelling narrative of the artistic and political development of an exceptional and yet quintessentially American figure."

—Art in America

“The most powerful moments of the exhibition have a moral grandeur rare in contemporary art, as it becomes clear that not only was Wojnarowicz fully cognizant of the tools being used against him, he made the onslaught the subject of his work.”

—The Washington Post