Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror

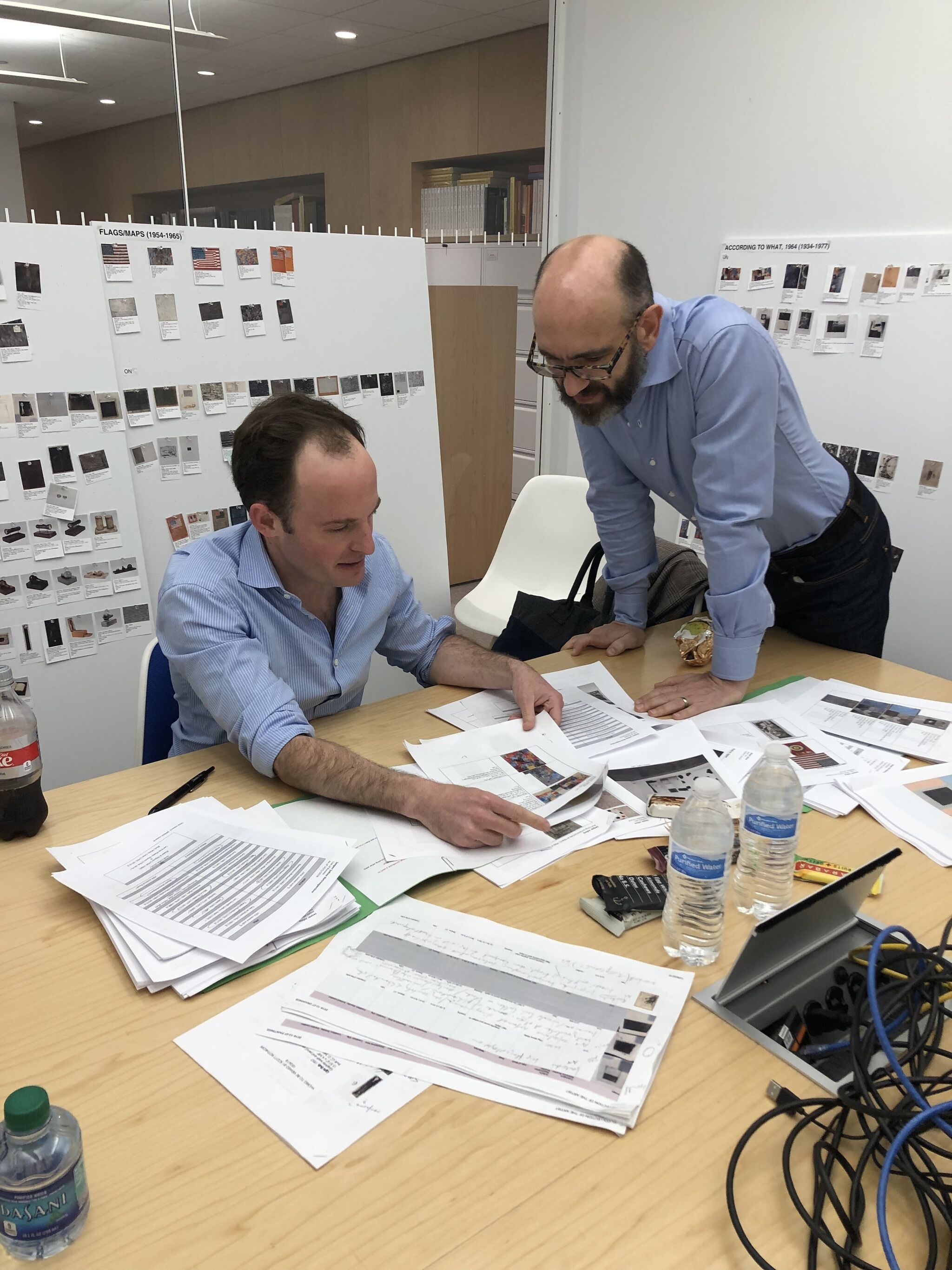

Scott Rothkopf, Senior Deputy Director and Nancy and Steve Crown Family Chief Curator

Related exhibition

The exhibition Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror is on view September 29, 2021 through February 13, 2022

Jasper Johns (b. 1930) has been making and showing his art for so long and so widely that it has come to seem like an immovable feature in a landscape against which contemporary life continues to unfold. At the time of this writing, Johns is nearly ninety-one years old and has been considered an important—if not the most important—living American artist for more than sixty years. This longevity is both easy to take for granted and hard to truly fathom, like the presence of subatomic particles or galaxies beyond our view. Few, if any, artists in history have existed in the shadow of such precocious achievement and influence for such a long time. Before turning thirty, Johns had made an indelible mark on the international art scene, and his ascent coincided with a growing and unprecedented international interest in contemporary art on the part of the press, museums, and an enthralled though sometimes skeptical public. By the time he reached fifty, he had been the subject of three New York museum retrospectives and landed on the front page of The New York Times for his record-setting prices, a dubious distinction in the annals of art if not the popular imagination. His work helped create the very conditions into which it was so smoothly assimilated—the conditions in which contemporary art and artists still largely exist today.

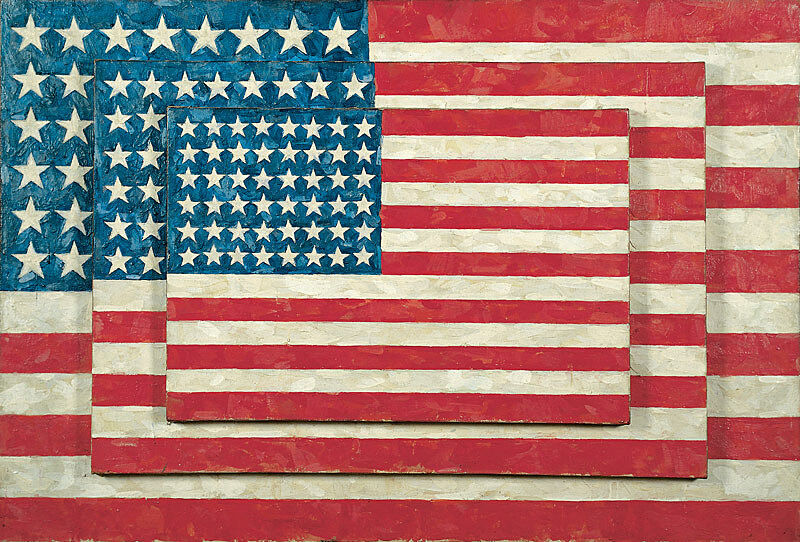

Johns gained immediate attention in the late 1950s for his paintings of flags, targets, and numbers, which remain the enduring emblems of his art. Yet nothing about these early paintings would predict the multifarious experiments of the decades that followed. Indeed, if one lined up the first five years of his work alongside random samples from the next sixty, an untrained eye might be hard-pressed to recognize them as the products of the same artist. Whatever the general conception of his work may be, Johns was surely not on autopilot. This was a point that curator Kirk Varnedoe argued in the catalogue of Johns’s fourth and, until now, most recent New York retrospective, at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1996–97.Kirk Varnedoe, “Fire: Johns’s Work as Seen and Used by American Artists,” in Jasper Johns: A Retrospective, ed. Kirk Varnedoe, exh. cat. (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1996), 93–115.He endeavored to pry loose Johns’s art from the restrictive and reductive amber that had calcified around it even then. Comparing Johns to the mythical figure of Prometheus, who stole fire from the gods, Varnedoe credited the artist with sparking countless new ideas. Just the first ten years of Johns’s mature work paved the way for Pop art, linguistically oriented Conceptualism, literalist painting and Minimalist sculpture, quasi-referential abstraction, process- and materials-based tendencies, and many more isms and trends that followed in his wake. Varnedoe’s account makes it difficult to imagine a modern artist who lit more fires faster, while continuing to blaze new trails of his own.

Despite Johns’s preternatural and protean impact, today his work can sometimes feel more rooted in the past than the present. Like an injection in art’s coursing vein, his hyperstimulating inventions were almost immediately absorbed and then outstripped by those of wilder progeny that now perhaps seem more of our time. Consider, the truculent, high-finish sculptures of Donald Judd or the omnivorous oeuvre of Andy Warhol, two artists who were born just before Johns and emerged just after him. Or take slightly younger figures such as Eva Hesse and David Hammons, whose work challenges traditional formats more obviously than Johns’s. As much as he shifted the course of art history, Johns has remained true to earlier modes of thinking and making—careful humanist inquiry, the easel picture, the graphite drawing, the canvas and the brush. Whether we see him as the last of a line, the first of one, or both is to a certain degree a matter of perspective, but he undeniably opened a door to our age. To trade one overreaching analogy for another, Johns might be less Prometheus than Moses, someone who led his people to the Promised Land but didn’t go inside.

This is one reason why Johns’s art presents such a pertinent and powerful model for reexamination: it helps us to understand an inflection point in history, to sense how we got from where we were to where we are. To appreciate this we cannot merely presume the disruptive impulse of his pictures, but rather we must envision them as the charged products of a moment and a mind. It can be hard to regain this spirit of discovery and éclat in objects that have assumed the patina and reverence of icons, yet to grasp fully Johns’s achievement we must try. This is one aim of Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror. My cocurator, Carlos Basualdo, and I have not approached this retrospective as a straightforward reconstruction of an oeuvre or a rote reaffirmation of its putative greatness. Rather, we have attempted to segment it into pointed, discontinuous chapters that rekindle a sense of brisk curiosity in both the works and their beholders. Our goal has been to make one of the best-known artists of the past century seem somewhat strange and unfamiliar, to make his older art feel as alive as when it was new and the new work equally crucial to his story. Johns still goes to the studio almost every day. In fickle times, his assiduousness and quiet evolution are scarce qualities from which we can learn a great deal.

We began work on this project in early 2016 at a time of concentrated interest in Johns’s work. The groundbreaking catalogues raisonnés of his paintings and sculptures and of his drawings, respectively, were nearing completion.Roberta Bernstein, Jasper Johns: Catalogue Raisonné of Painting and Sculpture, 5 vols. (New York: Wildenstein Plattner Institute, 2017); and Menil Collection, ed., Jasper Johns: Catalogue Raisonné of Drawing, 6 vols. (Houston: Menil Collection, 2018).The Broad in Los Angeles and the Royal Academy of Arts in London were preparing a traveling survey of his work that would reintroduce it to their audiences for the first time in many years.Roberta Bernstein, ed., Jasper Johns, exh. cat. (London and Los Angeles: Royal Academy of Arts in collaboration with the Broad, 2017).And Johns’s art, entering its seventh decade, was itself on the cusp of transition from the forlorn Regrets series to an even more mournful body of work centered on an image of James Farley, a grieving marine in Vietnam. All this auspicious energy galvanized Carlos and me to embark on the most comprehensive exhibition ever of Johns’s art, jointly organized by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art. Although Johns had been the subject of the 1996–97 retrospective at MoMA, the arc of his sedulous career had grown considerably since then, and we fixed on 2020 as an opportunity to celebrate the year he would turn ninety.

Each of us and our respective museums have had intimate relationships with Johns and his art, offering rich histories, expertise, and collections that would inform and support so ambitious a project. Our conjecture was that the unique contexts of the two institutions would shape a visitor’s experience in different ways. The Philadelphia Museum of Art is encyclopedic and historically inclined, positioning Johns in the near company of some of his most beloved European influences, including Paul Cézanne, Marcel Duchamp, and Pablo Picasso. The Whitney is more oriented toward younger artists, so that Johns’s work would be part of a lively dialogue with a new generation. But there remained a pressing obstacle: how the exhibition would unfold in time and space. Our two cities were too close—and the anticipated loans too dear—to imagine a show that traveled from one venue to the next over an extended duration. As a thought experiment, we wondered how a retrospective might play out simultaneously in two cities proximate enough that dedicated viewers could visit them both. Doubling the show in scale would allow for a much deeper investigation of a sprawling, labyrinthine oeuvre. We could look beyond greatest hits and paintings to surprising finds and in-depth treatments of Johns’s indispensable works on paper. More important, this doubling could foster our curatorial intent to revivify Johns’s art for both those familiar with it and for those encountering it with fresh eyes.

As soon as we decided to stage a single exhibition synchronously in two parts, the problem arose of how to make sense of the division. We recognized that the great majority of visitors would see only one of the presentations, so we needed to provide them with a coherent, self-sufficient narrative. But for those traveling between the two museums, the installations could not seem redundant. Why, after all, bother to mount two similar exhibitions at the same time? The sum of the experiences had to be greater than that of each part, and the novel structure had to convey conceptual integrity rather than caprice. One solution would have been to apportion Johns’s career chronologically or by medium between the museums, but that would give most visitors too partial an account. So instead we scoured Johns’s oeuvre for clues to an organizational framework that grew out of his art rather than one superimposed atop it. This bipartite structure would have to exploit the gap—in time and space—between the encounter in each city, creating the sense of a whole composed of two interrelated, echoing fragments. After nearly a year of research and debate, a compelling rubric emerged from Johns’s lifelong preoccupation with mirroring and doubling—crucial twin concepts that have served as both image and operation since the inception of his mature work.

Once identified, this principle proved omnipresent. Mirroring pervades numerous compositions based on bilateral symmetry, where the left and right halves of a work reflect each other. Some, such as Device (1961–62; p. 193, pl. 20) and Corpse and Mirror II (1974–75; pp. 178–79, pl. 2), play abstractly with the logic of similitude and difference, while the more recent Regrets and Farley series are impelled by a curiosity about how images metamorphose through a mirroring of their parts. In other works, key passages reflect one another across a horizontal seam, or Johns toys with mirror writing by reversing the letters in a title or his name, as in Mirror’s Edge (1992; p. 188, pl. 4). Pairs and doubles are even more ubiquitous. A single work often contains adjacent duplicate elements, such as flags or maps, or the uncanny pair of cast ale cans in the two editions of Painted Bronze (1960; p. 177, pl. 1; and p. 185, pl. 1). Later on, motifs often recur in less rigid arrangements within the same scene. Countless more works exist as cognates of one another, marked by shifts in scale, medium, or palette, as with the dozens of examples of an image executed in both color and black and white. Johns often pursues these experiments with matrices that aid in the reproduction (and, at times, reversal) of an image, such as stamps, silkscreens, and stencils, as well as the myriad tools of the printshop that have fueled his vast graphic corpus. Evident in all these instances and so many more, the mirror and the double thus suggested themselves as the devices—to borrow a typically Johnsian term—that would give the retrospective structure. They are not the exhibition’s theme but its organizational metaphor, a logic by which to articulate a single exhibition across two sites. But what then is reflected?

Early in our process, we decided that the chapters of the exhibition would not hew to given series or periods but would articulate Johns’s protean turns of mind. The aim would be to take viewers inside his work—if not quite his head—and give them various glimpses of the ideas, processes, moments, and themes that inform and animate his work. We ultimately selected ten discrete methodological lenses through which to consider his art. Some depend on long-standing readings of his work, such as a semiotic analysis of his use of common two-dimensional motifs, including flags and numbers. Others are less canonical and more expressive or essayistic—for example, a biographical reading of Johns’s art in relation to places in which he has lived and worked. Still others focus on key working methods, such as his abiding preoccupation with making suites of unique prints or his intermittent execution of large-scale paintings that anthologize previous works and inspire future ones. The title Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror speaks to the exhibition’s mirror structure and to its various reflections on the artist’s mind.

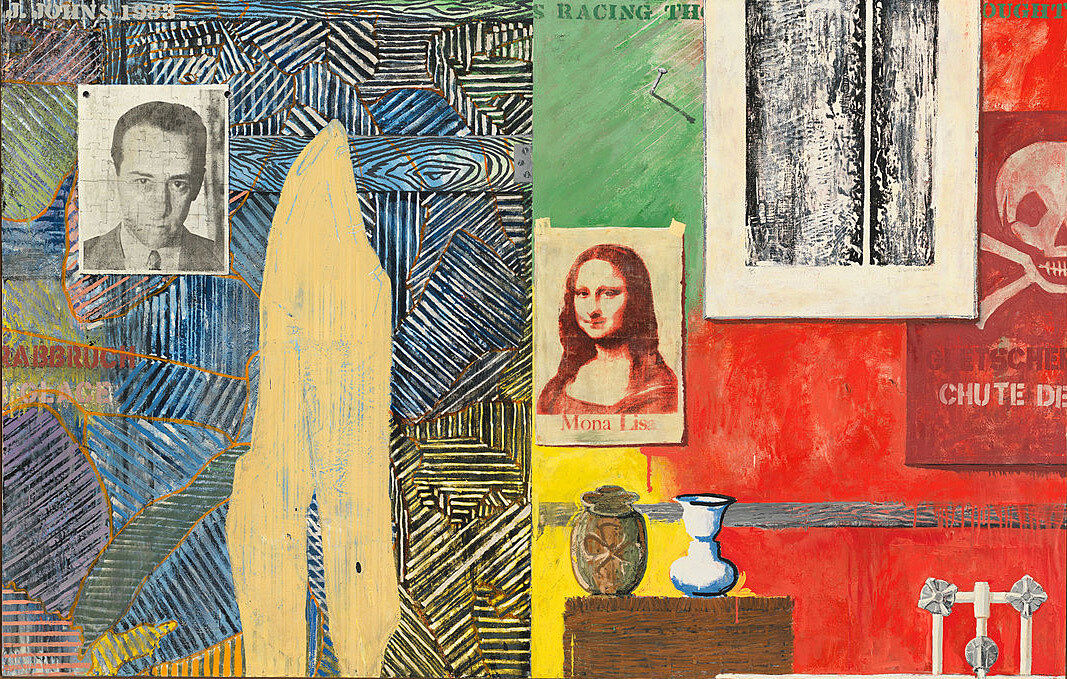

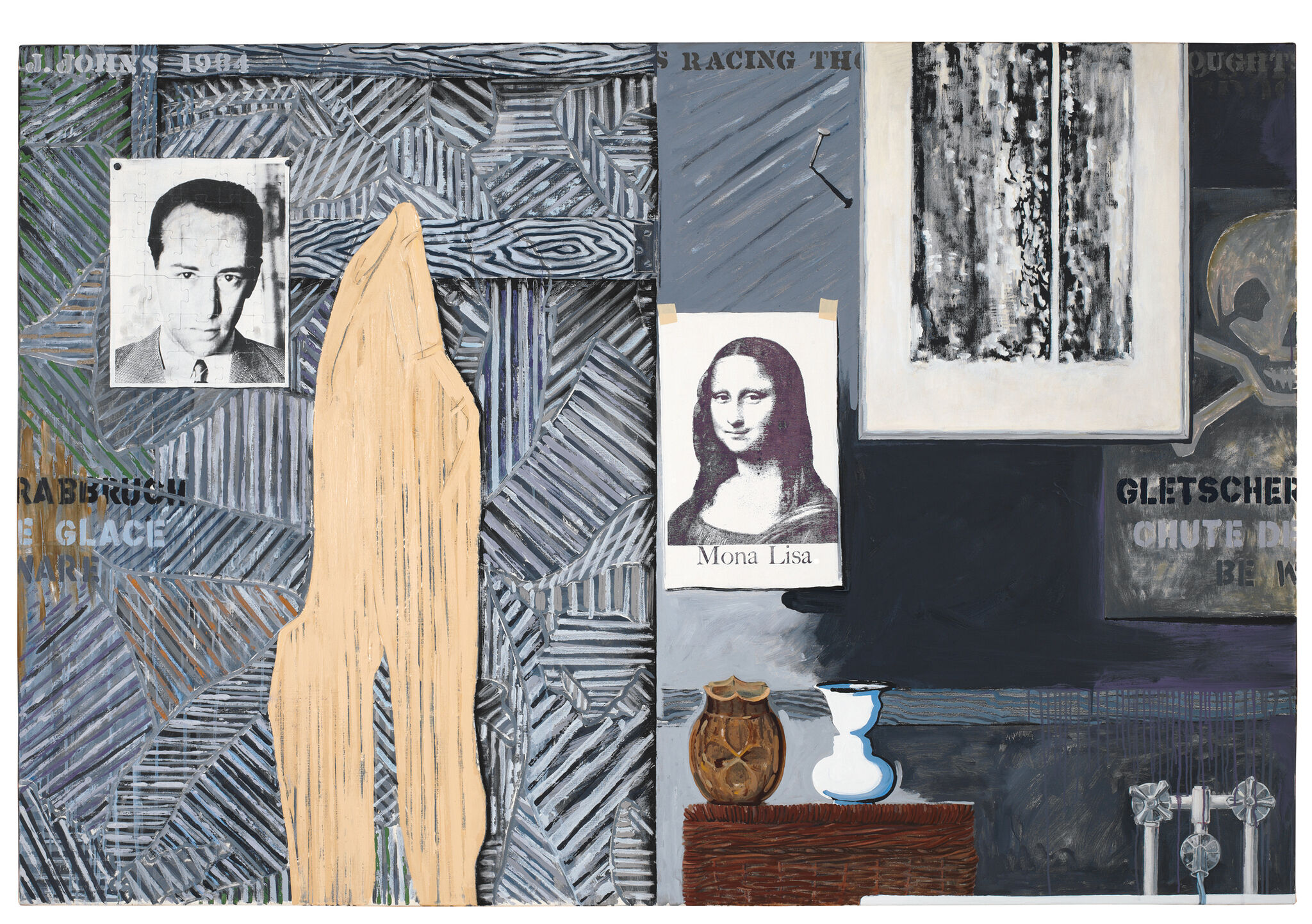

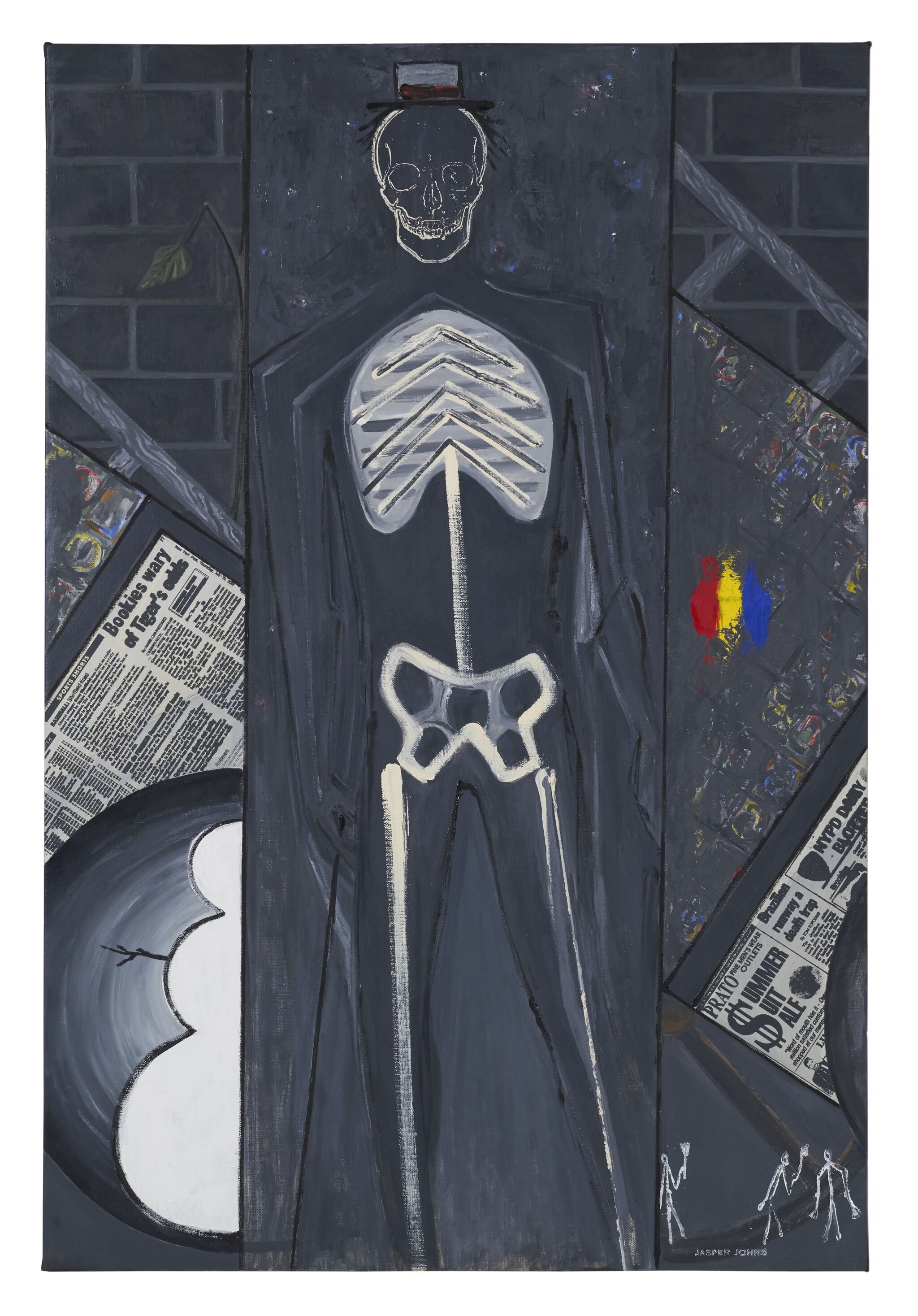

Each of these views on Johns’s art is articulated through two case studies presented, respectively, in Philadelphia and New York. Visitors to either venue encounter the same ten overarching ideas, but the supporting evidence through which these concepts are expressed differs completely at each site. So, for instance, at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the gallery exploring the importance of place probes deeply Johns’s relationship with Japan, while the one at the Whitney delves into South Carolina, where he grew up and later spent time as an adult. In New York, the gallery devoted to early motifs focuses on flags and maps; in Philadelphia, it envelops visitors in a profusion of numbers. In some cases, the cognate galleries each contain closely related works from the same series or vintage that are distinguished from one another through their contrasting emotional timbres. In Philadelphia, for example, Johns’s expressive turn to a surfeit of new imagery during the 1980s and 1990s takes on a nightmarish cast, while in New York many of the same subjects conjure a lighter, dreamy air. This yin-yang dynamic reverses in the subsequent galleries in each city, which concern Johns’s recent meditations on mortality. Pallid tones and an ethereal atmosphere predominate in the Philadelphia ensemble, while in New York agitated dusky surfaces evoke death and despair. In every case, we took pains not to privilege Johns’s “masterpieces” or rely solely on his most recognizable imagery but to mix them with less-known subjects and works on paper, some rarely or never before exhibited in public.

The galleries at both museums proceed largely in chronological order, although not without some curatorial sleight of hand. Several cognate rooms marshal works from the same period to support their twin takes on a common interpretive idea. For example, the galleries treating early motifs—numbers in Philadelphia, flags and maps at the Whitney—come second in the narrative sequence of each show, while the light and dark views on the most recent works conclude the coeval stories. In other cases, the cognate galleries explore the same concept at two distinct moments in Johns’s career, as in the rooms that re-create his solo exhibitions at the Leo Castelli Gallery in New York in 1960 and 1968. To maintain the chronological flow at each venue, the restaging of the 1960 room comes earlier in the Philadelphia enfilade than the 1968 room does at the Whitney. And this, conversely, implies the flip-flopping of another pair, so that the gallery unpacking According to What (1964; pp. 150–51, pl. 2) in New York precedes the one devoted to Untitled (1972; pp. 158–59, pl. 2) in Philadelphia. Such structural inversions are wholly invisible to a visitor at either venue, but those interested in unpuzzling the exhibition’s parallel plots will discover that their mirroring is purposefully imperfect. Indeed, the two halves of the exhibition are at once complete and commensurate while also partial and asymmetrical.

The two strands of the exhibition come together in a third site: the catalogue. A kind of Rosetta stone or decoder ring for the project as a whole, this volume is the only place where one encounters side by side the ten sets of dual case studies. A curatorial text introduces each methodological lens—or turn of mind—and its pair of supporting examples, followed by related images for each venue. On every spread, the reproductions are arranged as intricate visual essays. Sometimes, they expound on and amplify specific interrelationships explored in the galleries, while in other instances they present new connections not necessarily evident in the physical spaces of the exhibition. Each of these sections concludes with texts by a wide range of authors, from long-standing art-historical authorities on Johns’s work to artists, poets, and philosophers, most of whom are writing about his art for the first time. Their essays more or less obliquely expound on the curatorial theses and works in the paired galleries, often refracting them further through new contextual and interpretive prisms. The final, eleventh bipartite section points back to the exhibition’s actual sites at the Whitney and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Here, archival materials tell parallel histories of Johns’s deep and intimate relationship with each institution. Glimpses behind the backstage curtain, they thread the two venues directly into the site of the book. A coda on Johns’s sketchbooks provides another window into his mind and art.

Originally scheduled to appear in 2020, the exhibition arrives in 2021, having been postponed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It no longer celebrates Johns’s ninetieth birthday, and much has happened since then. Yet despite the upheavals of the intervening year, Johns’s example feels no less timely, nor does its study demand so pat an occasion. His constancy and patient dedication bracingly remind us of the importance of longer timelines, a life in the world and in art that carries on through many seasons. I remember an early conversation about the exhibition with Johns, in which I pointed out that when the show opened he would be ninety. I stumbled over whether to use the simple future or conditional tense. He paused before answering with his usual precision, “The possibility of my future existence has nothing to do with this show.” He was right, of course. It’s the art that lives on.

This essay is excerpted from Jasper Johns: Mind/Mirror, edited by Carlos Basualdo and Scott Rothkopf, published by the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art in association with Yale University Press © 2021.