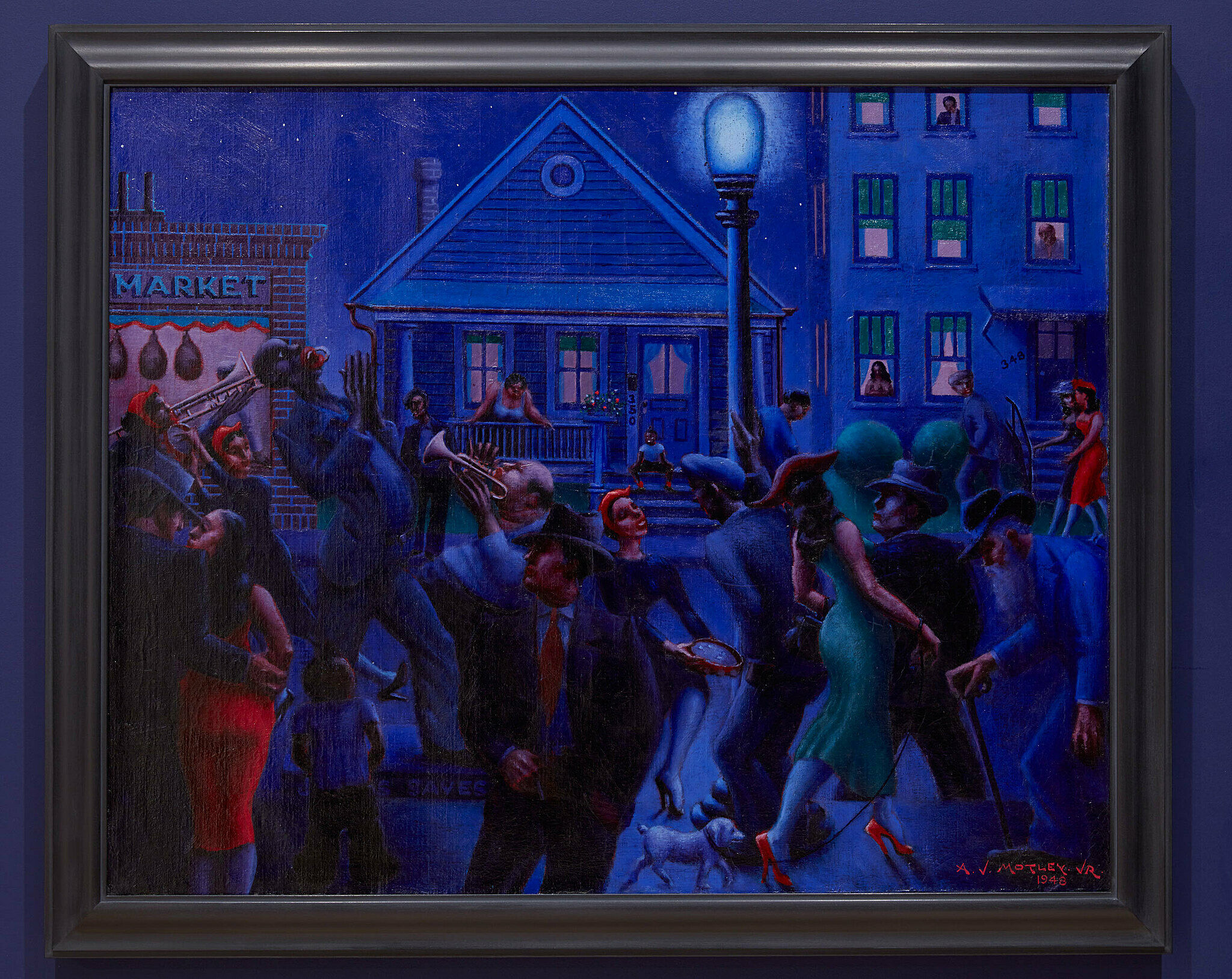

Archibald John Motley, Jr.

1891–1981

Introduction

Archibald John Motley, Jr. (October 7, 1891 – January 16, 1981), was an American visual artist. Motley is most famous for his colorful chronicling of the African-American experience in Chicago during the 1920s through 1940s, and is considered one of the major contributors to the Harlem Renaissance or New Negro Movement, a time in which African-American art reached new heights not just in New York but across America—its local expression is referred to as the Chicago Black Renaissance. Born in New Orleans and raised in Chicago, Motley studied painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago during the 1910s, graduating in 1918.

The New Negro Movement marked a period of renewed, flourishing black psyche. There was a newfound appreciation of black artistic and aesthetic culture. Consequently, many black artists felt a moral obligation to create works that would perpetuate a positive representation of black people. During this time, Alain Locke coined the idea of the "New Negro", which was focused on creating progressive and uplifting images of blacks within society. The synthesis of black representation and visual culture drove the basis of Motley's work as "a means of affirming racial respect and race pride." His use of color and varying visual representations of skin-tones, demonstrated his artistic portrayal of blackness as being multidimensional. Motley himself had mixed race ancestry, and often felt unsettled about his own racial identity. Thus, his art often demonstrated the complexities and multifaceted nature of black culture and life.

Wikidata identifier

Q4786462

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed January 31, 2026.