Beyond Documentation: Davarian Baldwin on Archibald Motley’s Gettin’ Religion

Mar 11, 2016

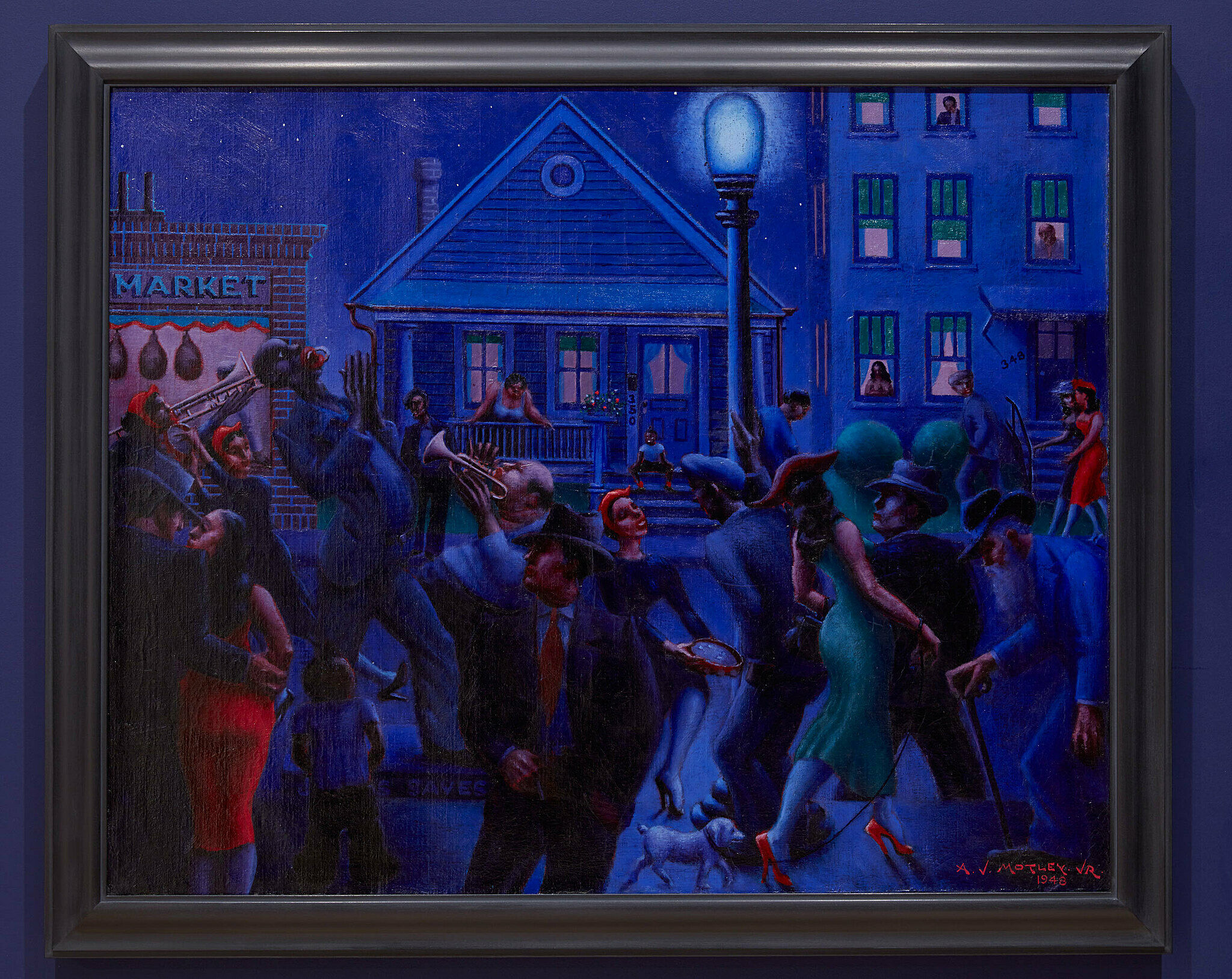

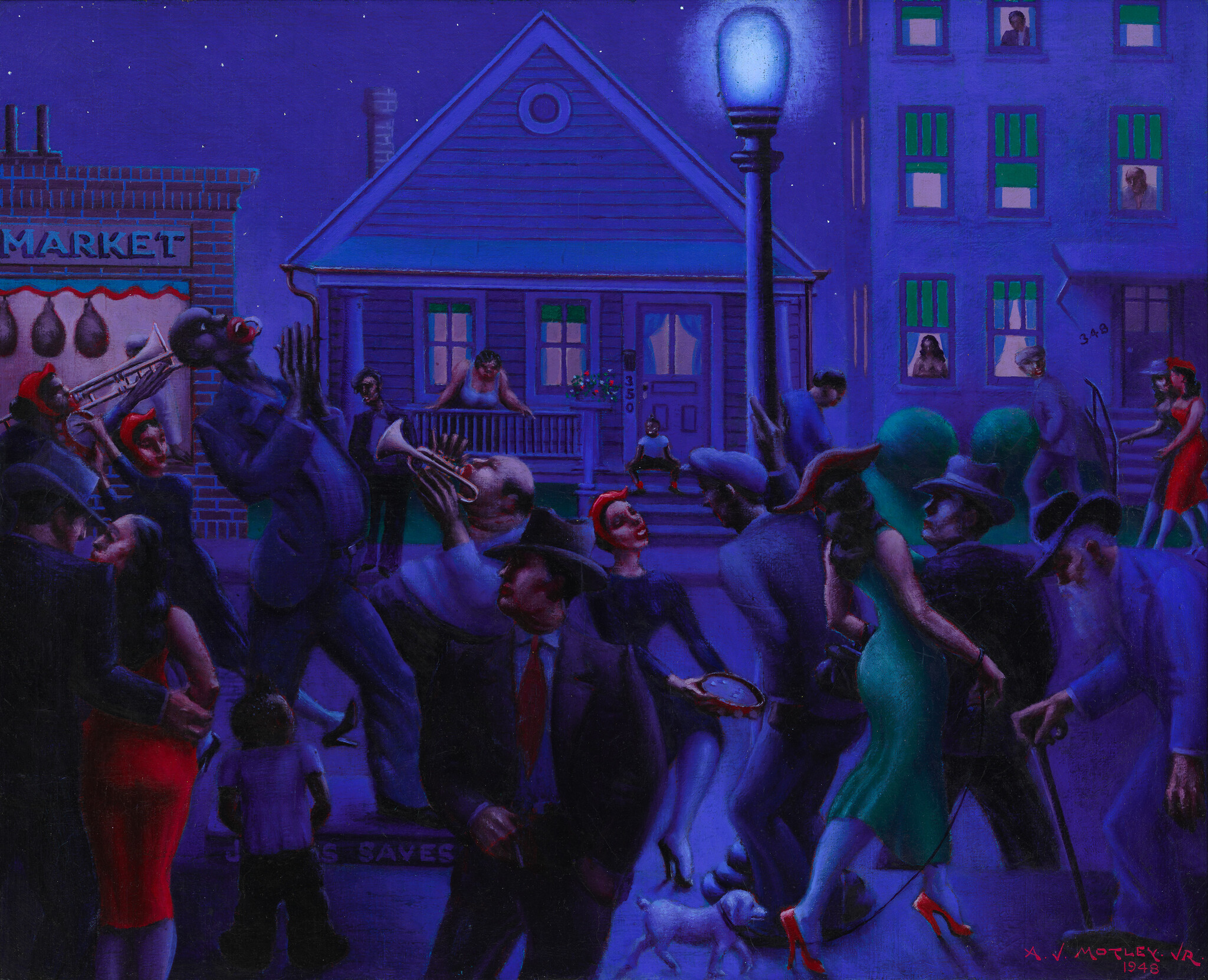

Gettin’ Religion (1948), acquired by the Whitney in January, is the first work by Archibald Motley to become part of the Museum’s permanent collection. Motley was the subject of the retrospective exhibition Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist, organized by the Nasher Museum at Duke University, which closed at the Whitney earlier this year. Described as a “crucial acquisition” by curator and director of the collection Dana Miller, this major work is currently on view on the Whitney’s seventh floor.

Davarian L. Baldwin is a scholar, historian, critic, and author of Chicago's New Negroes: Modernity, the Great Migration, and Black Urban Life, who consulted on the exhibition at the Nasher. In his essay for the exhibition catalogue, “‘Midnight was the day’: Strolling through Archibald Motley’s Bronzeville,” he describes the nighttime scenes Motley created, and situates them on “the Stroll,” the entertainment, leisure, and business district in Chicago’s Black Belt community after the First World War. In this interview, Baldwin discusses the work in detail, and considers Motley’s lasting legacy.

You’ve said that Gettin’ Religion is your favorite painting by Archibald Motley. Why is that?

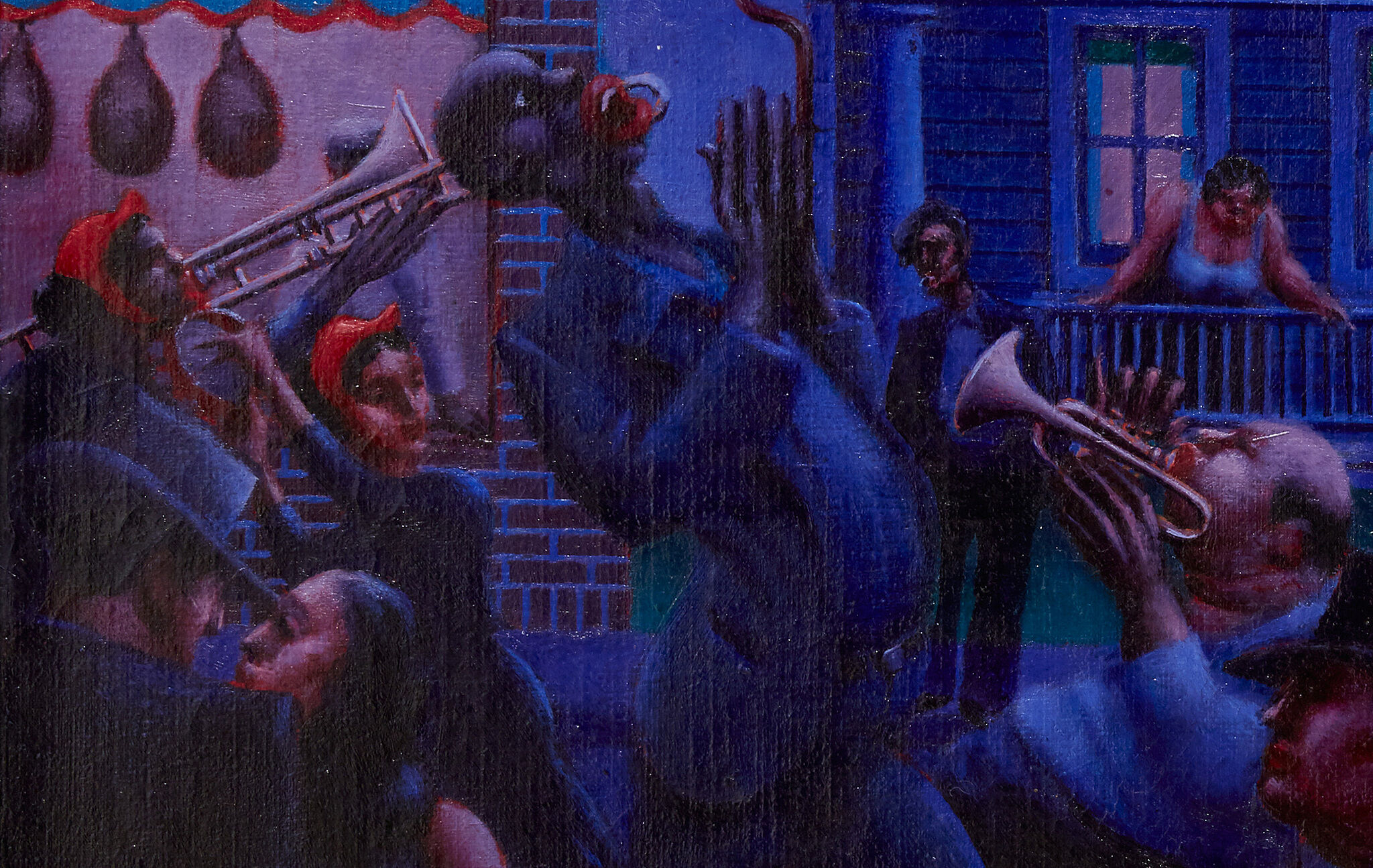

This piece gets at the full gamut of what I consider to be Black democratic possibility, from the sacred to the profane, offering visual cues for what Langston Hughes says happened on the Stroll: [Thirty-Fifth and State was crowded with] “theaters, restaurants and cabarets. And excitement from noon to noon. Midnight was like day. The street was full of workers and gamblers, prostitutes and pimps, church folks and sinners.” Langston Hughes’s writing about the Stroll is powerfully reflected and somehow surpassed by the visual expression that we see in a piece like Gettin’ Religion.

Some individuals have asked me why I like the piece so much, because they have a hard time with what they consider to be the minstrel stereotypes embedded within it. You have this individual on a platform with exaggerated, wide eyes, and elongated, red lips. Many people are afraid to touch that. Given the history of race and caricature in American art and visual culture, that gentleman on the podium jumps out at you. [There’s a feeling of] not knowing what to do with him. And I think Motley does that purposefully. What’s interesting to me about this piece is that you have to be able to move from a documentary analysis to a more surreal one to really get at what Motley is doing here. What I find in that little segment of the piece is a lot of surreal, Motley-esque playfulness. This figure is taller, bigger than anyone else in the piece. He’s standing on a platform in the middle of the street, so you can't tell whether this is an actual person or a life-size statue. Why would a statue be in the middle of the street? What is Motley doing here?

The platform he’s standing on says “Jesus Saves.” It’s a phrase that we also find in his piece Holy Rollers. On one level, this could be Motley's critique, as a black Catholic, of the more Pentecostal, expressive, demonstrative religions; putting a Pentecostal holiness or black religious official on a platform of minstrel tropes might be Motley’s critique of that style of religion.

But it also could be this wonderful, interesting play with caricature stereotypes, and the in-betweenness of image and of meaning. This is a transient space, but these figures and who they are are equally transient. Is that an older black man in the bottom right-hand corner? Is it an orthodox Jew? Is the couple in the bottom left hand corner a sex worker and a john, or a loving couple on the Stroll?

In the back you have a home in the middle of what looks like a commercial street scene, a nuclear family situation with the mother and child on the porch. The woman is out on the porch with her shoulders bared, not wearing much clothing, and you wonder: Is she a church mother, a home mother? Is she the mother of a brothel? What is going on?

Gettin' Religion is again about playfulness—that blurry line between sin and salvation. At nighttime, you hear people screaming out “Oh, God!” for many reasons. [The painting] allows for blackness to breathe, even in the density. From the outside in, the possibilities of what this blackness could be are so constrained. He keeps it messy and indeterminate so that it can be both. Polar opposite possibilities can coexist in the same tight frame, in the same person.

What does it mean for this work to become part of the Whitney’s collection?

I think it's telling that when people want to find a Motley painting in New York, they have to go to the Schomberg Research Center at the New York Public Library. Motley was putting up these amazing canvases at a time when, in many of the great repositories of visual culture, many people understood black art as being folklore at best, or at worst, simply a sociological, visual record of a people. In the grand halls of art—including institutions like the Whitney—this work would not have been fondly embraced for its intellectual, creative, and even speculative qualities. Therefore, the fact that Gettin' Religion is now at the Whitney signals an important conceptual shift. It forces us to come to terms with this older aesthetic history, and challenges the ways in which we approach black art; to see it as simply documentary would miss so many of its other layers.

I think in order to legitimize Motley’s work as art, people first want to locate it with Edward Hopper, or other artists that they know—Reginald Marsh. I think that's true in one way, but this is not an aesthetic realist piece. It can't be constrained by social realist frame. I believe that when you see this piece, you have to come to terms with the aesthetic intent beyond documentary.

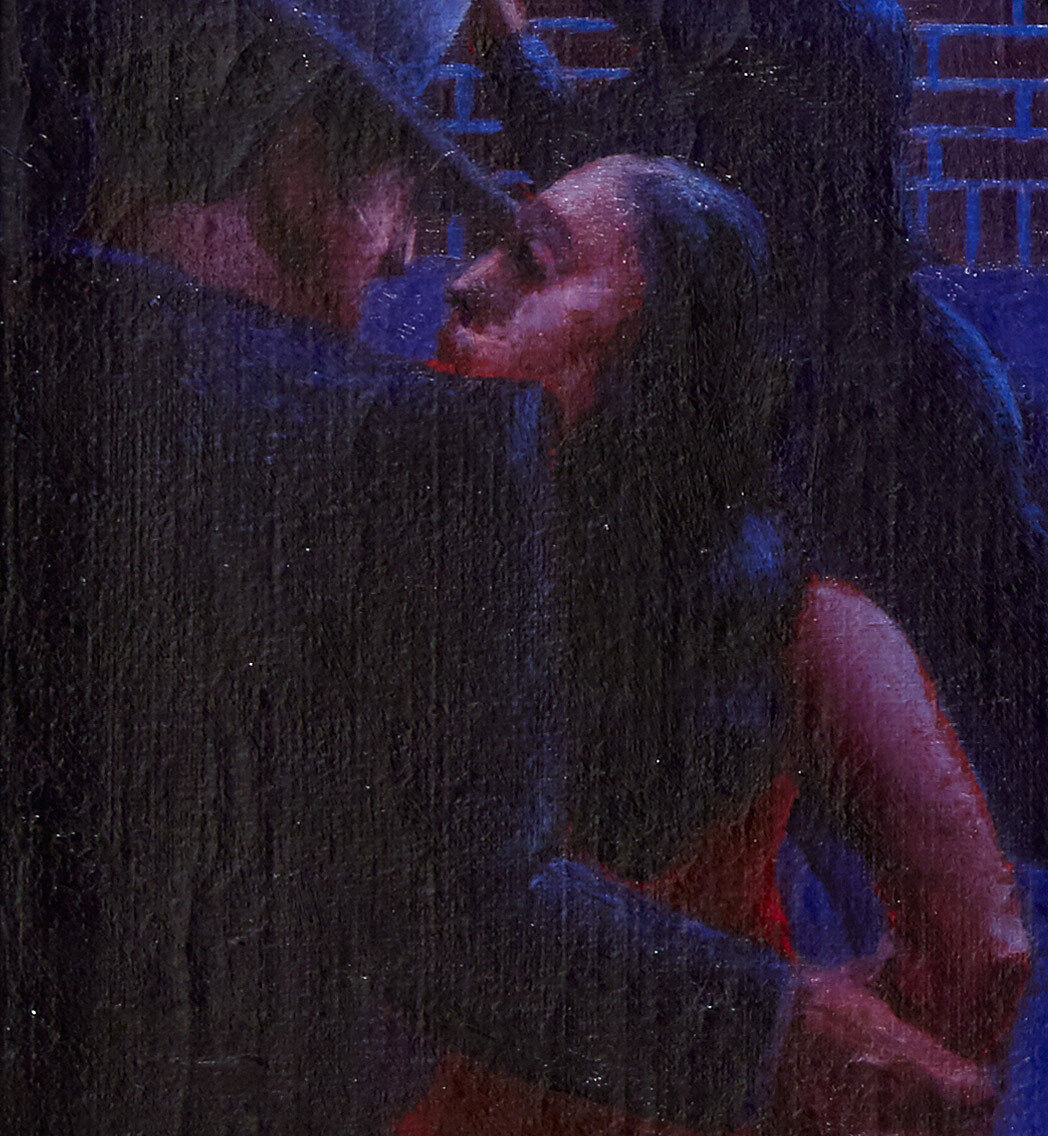

Did Motley put himself in this painting, as the figure that's just off center, wearing a hat?

Richard Powell, who curated the exhibition Archibald Motley: Jazz Age Modernist, has said with strength that you find a character like that in many of Motley's paintings, with the balding head and the large paunch. I'm not sure, but the fact that you have this similar character in multiple paintings is a convincing argument. He is kind of Motley’s doppelganger.

My take: [The other characters playing instruments] are all going to the right. But then, the so-called Motley character playing the trumpet or bugle is going in the opposite direction. At first glance you're thinking he’s a part of the prayer band. But on second notice, there is something different going on there.

How would you describe Motley’s significance as an artist?

I call Motley the painter laureate of the black modern cityscape. That’s my interpretation of who he is. What's powerful about Motley’s work and its arc is his wonderful, detailed attention to portraiture in the first part of his career. It doesn’t go away; it gets incorporated into these urban nocturnes, these composition pieces. There is a series of paintings, like Gettin’ Religion, Black Belt, Blues, Bronzeville at Night, that in their collective body offer a creative, speculative rendering—again, not simply documentary—of the physical and historical place that was the Stroll starting in the 1930s. I see these pieces as a collection of portraits, and as a collective portrait.

Motley's paintings are a visual correlative to a vital moment of imaginative renaming that was going on in Chicago’s black community. The black community in Chicago was called the Black Belt early on. Black Chicago in the 1930s renamed it Bronzeville, because they argued that Black Belt doesn't really express who we are—we're more bronze than we are black. At the same time, while most people were calling African Americans negros, Robert Abbott, a Chicago journalist and owner of The Chicago Defender said, "We aren’t negroes, we are The Race. We’re not a race, but The Race. So, you have the naming of the community in Bronzeville, the naming of the people, The Race, and Motley's wonderful visual representations of that whole process.

[The Bronzeville] community is extremely important because on one side it becomes this expression of segregation, and because of this segregation you find the physical containment of black people across class and other social differences in ways that other immigrant or migrant communities were not forced to do. On the other side, as the historian Earl Lewis says, it’s this moment in which African Americans of Chicago have turned segregation into congregation, which is precisely what you have going on in this piece. It's a moment of explicit black democratic possibility, where you have images of black life with the white world certainly around the edges, but far beyond the picture frame. There is a certain kind of white irrelevance here. That, for me, is extremely powerful, because of the democratic, diverse rendering of black life that we see in these paintings. There is always a sense of movement, of mobility, of force in these pieces, which is very powerful in the face of a reality of constraint that makes these worlds what they are. In the face of a desire to homogenize black life, you have an explicit rendering of diverse motivation, and diverse skin tone, and diverse physical bearing.

This work is not documenting the Stroll, but rendering that experience. That’s what’s powerful to me. We know factually that the Stroll is a space that was built out of segregation, existing and centered on Thirty-Fifth and State, and then moving down to Forty-Seventh and South Parkway in the 1930s. In the face of restrictions, it became a mecca of black businesses, black institutions—a black world, a city within a city. We know that factually. But we get the sentiment of that experience in these pieces, beyond the documentary.

You describe a need to look beyond the documentary when considering Motley’s work; is it even possible to site these works in a specific place in Chicago?

Motley has this 1934 piece called Black Belt. So that’s historical record; we know that's what it was called by the outside world. And then we have a piece rendered thirteen years later that's called Bronzeville at Night. We have a pretty good sense that these urban nocturne pieces circulate around what we call the Stroll, or later called the Promenade when it moved to Forty-Seventh and South Parkway.

But in certain ways, it doesn't matter that this is the actual Stroll or the actual Promenade. Because of the history of race and aesthetics, we want to see this as a one-to-one, simple reflection of an actual space and an actual people, which gets away from the surreality, expressiveness, and speculative nature of this work. [The painting is] rendering a sentiment of cohabitation, of activity, of black density, of black diversity that we find in those spaces—and that’s where I want to stay. I think that’s what made it possible for places like the Whitney to be able to see this work as art, not just as folklore, and why it's taken them so long to see that.

With details that are so specific, like the lettering on the market sign that's in the background, you want to know you can walk down the street in Chicago and say that’s the market in Motley’s painting. What I’m saying is instead of trying to find the actual market in this painting, find the spirit in it, find the energy, find the sense of what it would be like to be in such a space of black diversity and movement.

At her New Year's Eve performance, jazz performer and experimentalist Matana Roberts expressed a “distinct affinity” for Motley's work. How do you think Motley’s work might transcend generations?

These paintings come to not just represent a specific place, but to stand in for a visual expression of black urbanity. The actual buildings and activities don't speak to the present. But if you live in any urban, particularly black-oriented neighborhood, you can walk down a city block and it's still [populated] with this cast of characters. There are certain people that represent certain sentiments, certain qualities. It's literally a stage, and Motley captures that sense. The painting is depicting characters without being caricature, and yet there are caricatures here. So again, there is that messiness.

What do you hope will stand out to visitors about Gettin’ Religion among other works in the Whitney's collection?

At best, I hope that it leads people to understand that there is this entirely alternate world of aesthetic modernism, and to come to terms with how perhaps the frameworks they’ve learned about modernism don't necessarily work for this piece. I hope it leads them to further investigate the aesthetic rules, principles, and traditions of the modernism—the black modernism—from which this piece came, not so much as a surrogate of modernism, but a realm of artistic expression that runs parallel to and overlaps with mainstream modernism. There are other cues, other rules, other vernacular traditions from which this piece draws that cannot be fully understood within the traditional modernist framework of abstraction or particular artistic circles in New York. So I hope they grow to want to find out more about these traditions that shaped Motley’s vibrant color palette, his profound use of irony, and fine grain visualization of urban sound and movement.

Gettin’ Religion is on view on floor seven as part of The Whitney’s Collection.