Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables | Art & Artists

Mar 2–June 10, 2018

Grant Wood: American Gothic and Other Fables | Art & Artists

Portraits

3

By the late 1920s, Grant Wood had come to believe that the emergence of a rich American culture depended on artists breaking free of European influence and expressing the specific character of their own regions. For him, it was Iowa, whose rolling hills and harvested cornfields served as the background for his earliest mature portraits, those of his mother and Arnold Pyle. In Europe, he had admired Northern Renaissance painting by artists such as Hans Memling and Albrecht Dürer. By the time he painted American Gothic in 1930, he had concluded that the hard-edge precision and meticulous detail in their art could be used to convey a distinctly American quality, especially suggestive of the Midwest. Joined with Iowan subject matter, it became the basis of his signature style.

Wood felt that all painting, portraiture included, must suggest a narrative in order to engender the emotional and psychological engagement he associated with successful literature. Consequently, he included images that hinted at the life and character of the depicted subject, taking care to avoid anecdotal illustration by painting archetypes rather than individuals. He left the “props” in his portraits intentionally ambiguous, making the stories they intimate so enigmatic that they defy ready explanation; they are puzzles to be deciphered by viewers based on their individual attitudes and experiences. As a result, Wood’s portraits have historically invited multiple interpretations.

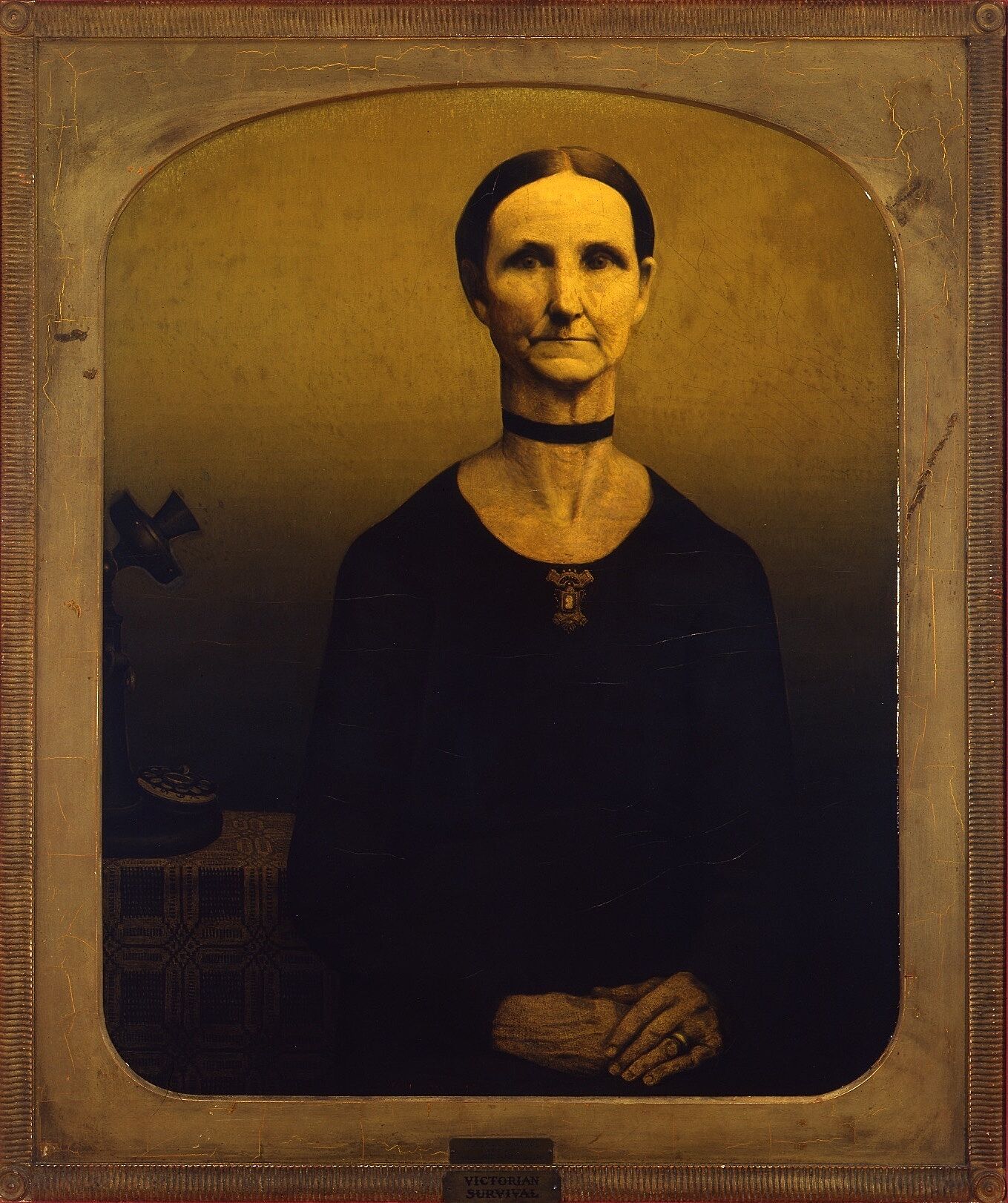

Victorian Survival, 1931

With its rounded edges, elaborate frame, and sepia tones, Victorian Survival purposely resembles the late-nineteenth-century tintype of Wood’s great aunt on which this work is modeled. With her stiff upright pose—accentuated by her long choker-bound neck—and tightly combed hair, the sitter’s old-fashioned demeanor contrasts sharply with the modern technology of the rotary dial phone. As always, Wood’s ambiguous symbolism inspires many interpretations. To some the contrast between the figure and the telephone is a humorous commentary on the trope of the gossipy spinster, while to others it has been interpreted as a clash between Victorian insularity and modernity.