Timeless Form

It seems that we are always running out of time, languishing in pandemic time, rushing to be on time, or making time. We also understand that our perception of time is elastic, ever-changing, and ungraspable. Either it is time for a change, or we arrive just in the nick of time. Time seems to completely control us, yet we remain at a loss as to how to spend it or accept its inevitable progression forward. We are told to balance, manage, optimize. It is as if the more we try to fix time, the more it slips away.

Although it is a medium that is experienced by the viewer as static, photography is completely reliant upon time. At its most simplified, the two core operations of photography are light and time; how much light is let into the camera for how long determines the final image. It is natural then that artists engaging with a medium reliant on time probe these ideas, proposing a variety of ways to depict and imagine it—something so undeniable yet difficult to define. The exhibition Time Management Techniques spans the 1960s to today and includes works from the Whitney’s permanent collection by Blythe Bohnen, Shannon Ebner and David Reinfurt, Darrel Ellis, Muriel Hasbun, Corin Hewitt, EJ Hill, Sky Hopinka, Katherine Hubbard, Dawn Kasper, and Lew Thomas. These artists use a wide range of processes and formal and conceptual strategies to challenge the kind of time that so many of us feel subjected to, especially in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries: an optimized, forwardly progressing, regulated sense of time.

In an age when picture making is so common and automatic as to nearly be a habitual part of our contemporary existence, it requires some effort to remember that photography has not always been a digital act of quick capture. For much of its relatively short existence since its beginning in the nineteenth century, photography has often been a laborious process, requiring heavy, complicated equipment, precise conditions, and long exposures. These time-consuming processes required specific chemicals, repeated adjustments in light, skill, and some element of chance. Given the increased proliferation of digital technologies most of these steps have been automated and collapsed together: the impulse to document, frame, capture, and perceive is completed in seconds. In this contemporary moment, these modes are nearly indistinguishable from one another and, as such, signal a fundamental shift in the perception of what photography is and how we relate to it. This ubiquitous instantaneity obscures photography’s other registers, the ones that are slower and recursive. These eleven artists, all working during decades when photography was broadly accessible and not relegated to the realm of a professional, each arrive at this subject along a different path, but together they provide complex alternatives to thinking about how we experience time.

Process

Four of the artists in this exhibition use the camera to record their processes, inscribing their final works with the traces of how they were made. In doing so, these photographers forcefully work against the instantaneity implied by the medium, demonstrating its capacities to reflect a kind of patient, languid—and often systematic—experience of time unfolding.

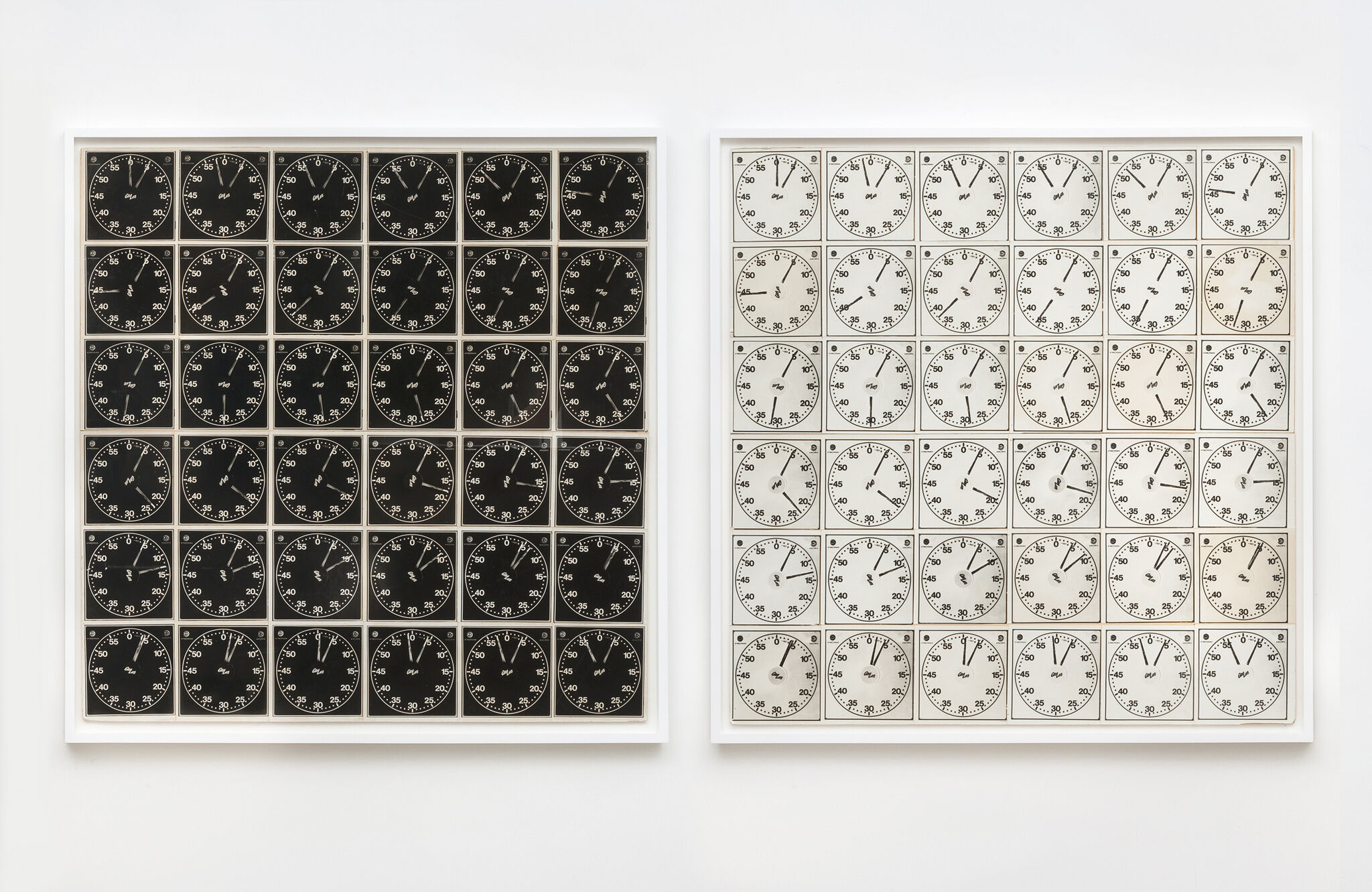

Blythe Bohnen and Lew Thomas both strip their processes of anything extraneous, breaking it apart to understand the most essential processes and aesthetic structures underlying their works. As Thomas said of his early explorations in the 1970s: “The work has no hidden messages. The work was physical and opaque, its object being nothing more than the systematic exploration of the photographic process and its corresponding structure.”Thomas Lew, Structural(ism) and Photography (San Francisco: NFS Press, 1978), 9. This led Thomas to repeatedly photograph the clock in his dark room, tracking its hands as the minutes passed. He explained: “Irrelevant details complicating the subject of Time were eliminated until I had reduced the process to a camera, a roll of film, and a lab clock. . . . I soon found procedure and process to be significant levels of construction indistinguishable from the content.”Lew, Structural(ism) and Photography, 9. For Thomas, subject and concept were one in the same as he attempted to depict this intangible force in works such as TIME EQUALS 36 EXPOSURES (positive and negative sections) (1971). Thomas slows down the photographic process, placing the clock that is crucial to developing film and printing photographs at the center of the work. In doing so, he reveals and reinforces the rigid and linear structures of measuring time.

In 1968 Bohnen was similarly attempting to strip her work of anything extraneous in order to point toward time’s other qualities. In the series Marking four points equidistant from a center and from each other, pencil on paper and time lapse photograph (1968), she marks four points on a blank sheet of paper with a pencil, using a camera to record the motions of her hand and pencil as they move together across the paper. In each diptych the four drawn marks are nearly identical, yet the shape that is captured by the camera is distinct, dependent on the path of her movements. As Bohnen described: “By coinciding, they go beyond sequential time to timeless form. By having the form circle to imitate form, I turn progression into a non-linear cycle. I never wanted to do progressions. Time is static—one goes in and out of levels of reality—not in progression, but simultaneous (or shifting) awareness.”Notebook, undated, personal archive of Blythe Bohen; emphasis in original.

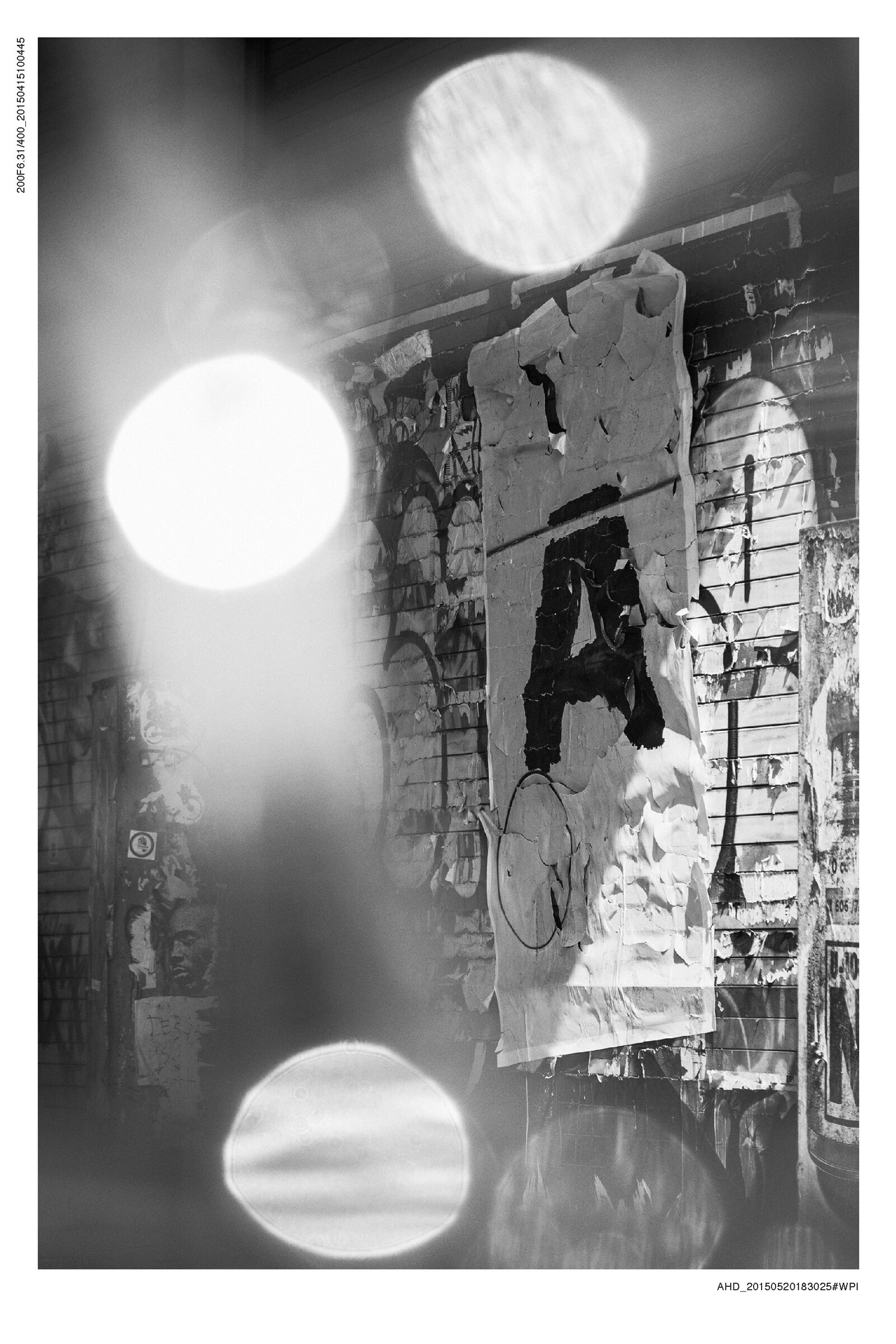

Shannon Ebner and David Reinfurt also use the camera to bear witness to the accrual of time. At the invitation of the High Line, they made posters using images from Ebner’s Black Box Collision A (2013– ), a long-running series of Ebner’s photographs of the letter A found on advertisements and signage. Returning this found typography to the kinds of public spaces in which it had originated, the artists hired a commercial wheat pasting company to hang the posters in the Manhattan neighborhoods of the Meatpacking District and Chelsea during the first week of every month. Before they were inevitably worn and destroyed by human and natural elements, Timothy Schenck, a frequent photographer of the High Line, documented the posters, capturing the original typography as well as its new surroundings. The series lasted a full year and resulted in twelve posters. Various registers of time course through this collaborative project, stitching together old and new work, numerous contributors, and neighborhoods undergoing rapid evolution.

Like Ebner’s work, Katherine Hubbard’s series Bend the rays more sharply… (2016) relies on a rigid, progressive structure. In this work, Hubbard uses repetition to explore cyclical experiences of time. Produced inside her custom-fitted darkroom, Hubbard used specially designed apparatuses to freeze sheets of film inside of blocks of ice. The resulting photographs are unexpectedly lyrical and enigmatic, seemingly abstract even while they are documentations of ice, itself a fleeting substance.

Structure and system underpin all four of these artists’ projects, echoing the ways in which time is systematized, divided, and marked. Their results, however, are often skeptical rather than supportive of this analytical way of approaching time. The works are inconclusive, presenting the structures we associate with time while opening a door to other modes of perception and, ultimately, allowing for the beauty of unresolved questions.

Performance

Blythe Bohnen and Katherine Hubbard’s processes involve practiced choreography that puts their work in dialogue—intentionally in Hubbard’s case—with performance. Shannon Ebner’s durational engagement activates the street almost as a stage and passersby as the audience, while Hubbard’s repetitive and controlled movements in her darkroom echo the more public performances she includes as part of each of her projects. The relationship between photography and performance is a long one, although photography has often played a supportive role in performance-based practices. Frequently, artists use the tool to document their performances, either themselves or in collaboration with another photographer. These records are sometimes transformed into standalone works or, more frequently, exist as documentary material allowing these otherwise ephemeral works to have an archival presence.

The performance-based artists included in this exhibition use the camera to punctuate their durational performances, pointing to the unrepeatable and unrecordable expanses of time in which they undertake their live works, rather than attempting to create a record of the live events themselves. For three of these artists—Corin Hewitt, Dawn Kasper, and EJ Hill—the exhibitions they were invited to take part in served as the temporal container for their projects. Each of these artists took up residence at museums for the entire length of an exhibition, performing inside the spaces that they were allotted and the containers that they created; they also made photographs as a way of marking the time of their endeavors.

For Hewitt, photography was an intrinsic part of Seed Stage (2008–9), the end product of material manipulations with organic and inorganic materials. His installation, a self-contained, walled-off workspace inside of a small gallery in the Whitney’s former uptown location, was a workshop/science lab/kitchen/photo studio, filled to the brim with equipment and materials that Hewitt combined and recombined in often untraditional ways. He cooked, fermented, composted, photographed, sculpted, and more, which meant that otherwise incompatible undertakings—like making breakfast and perfecting works of art—bled into one another. Hewitt staged and photographed the results of these experiments, adding rejected prints to the compost pile and displaying others on the gallery walls surrounding his installation. These process-based images served as a kind of calendar for the performance.

Kasper and Hill’s photographs are much more loosely tethered to their original performances than Hewitt’s. They do not record for posterity the sites of their work or anything that they themselves produced. Kasper’s photographs record objects that she was given during the course of her residency at the Whitney Biennial in 2012; they act as stand-ins for the relationships she made during the twelve weeks of the exhibition. Titled to acknowledge the givers of these gifts, these humble objects are reproduced as large-scale images, indicating the importance of this interpersonal exchange to her project.

Hill’s photographs of Los Angeles are seemingly the most loosely connected to his project at the Hammer Museum, taking place fully outside of the bounds of the performance itself. Of these three artists, Hill’s performance was the most circumscribed; he stood motionless on a gold-medal podium every hour the exhibition was open to the public. As he said about this performance: “This isn’t our game. We’re in this thing that wasn’t designed for us. It still grinds on us. . . . It’s hard being Black, brown, and queer. It’s hard to be alive in spaces that are designed to kill you. But there I am, still standing.”Carolina Miranda, “EJ Hill stood on a podium at the Hammer for 78 days in a work about race, art and winning,” Los Angeles Times, September 24, 2018 (accessed November 22, 2022). On his days off, the artist walked around the Los Angeles neighborhood where he grew up. The photographs that he took on these walks have a diaristic quality. They are beautiful and compelling yet ultimately withholding of the personal significance that they hold for Hill. As one critic wrote about his performance, “in late capitalist culture where we are trained to pursue and achieve and advance and consume and forget, stilling one’s life to make time to stand and remember is an act of ultimate resistance.”Litia Perta, “EJ Hill’s Art for Bodies that Refuse to Comply,” Hyperallergic, October 13, 2018 (accessed November 22, 2022).

These three performances and their resulting photographic companions all explore metamorphosis through repetition while asking viewers to consider how deep and expansive time can be even when it appears to be standing still.

Archive

Corin Hewitt, Dawn Kasper, and EJ Hill’s works all reflect on the changes that time can impart almost invisibly while circumstances appear to remain the same. Like many other artists in the show, they use these photographic reflections on their performances to reflect a kind of simultaneity of experience. Blythe Bohnen reflected on time’s quality of “simultaneous (or shifting) awareness,” and it is this element that Darrel Ellis, Muriel Hasbun, and Sky Hopinka are highlighting in their multivalent works. They engage directly with memory, exploring and exploiting its power as well as its fallibility.

Memory is our primary connection to our pasts, but it is neither static nor accurate. It skips and stutters, accrues and deletes. As it informs and morphs our experience of the present, it is also highly susceptible to outside influences such as the memories of others or family photographs. Ellis, Hasbun, and Hopinka are directly engaging with their familial histories and how the specificity of their stories necessarily intersects with the larger socio-political forces that shape and define how our stories unfold and are told.

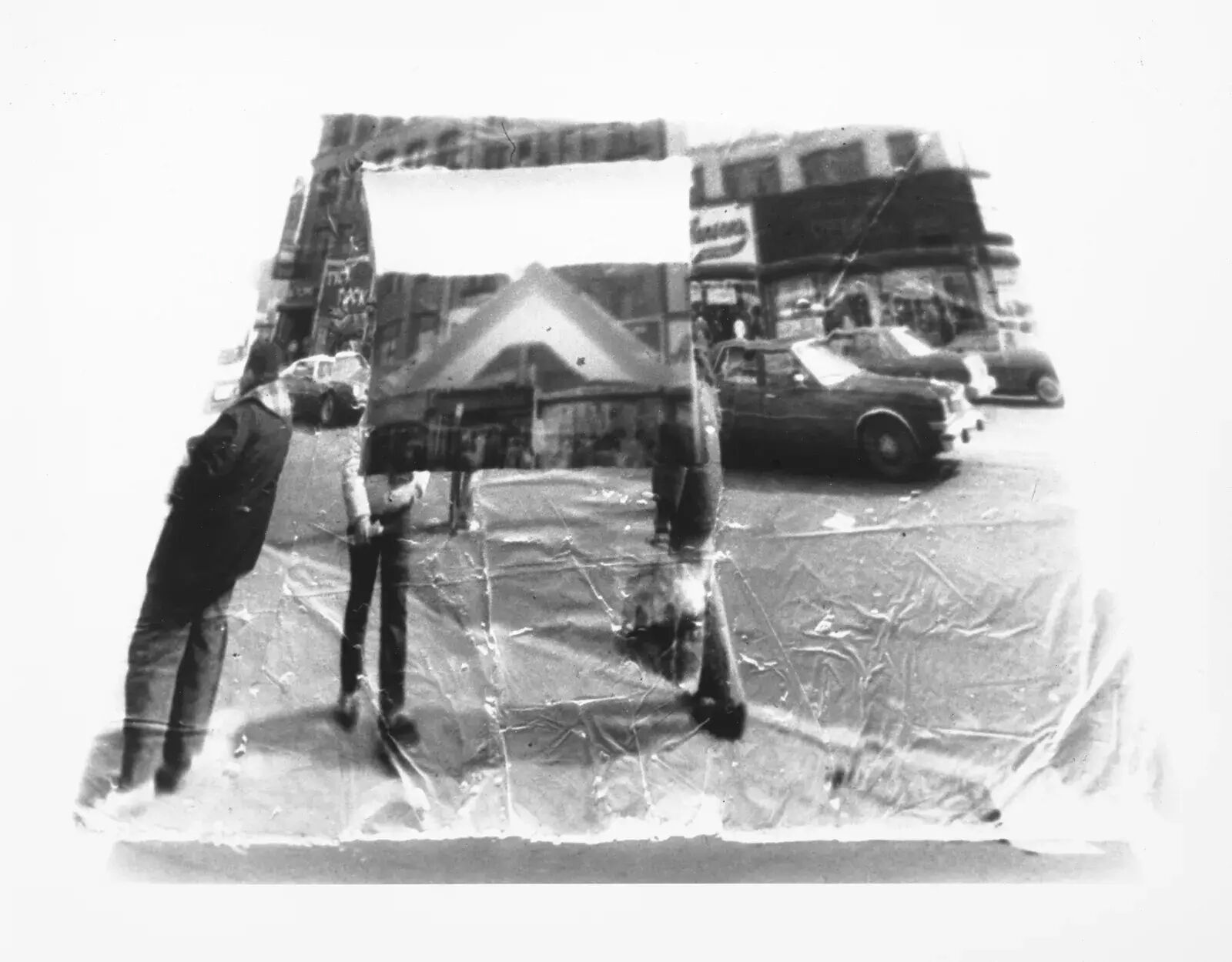

Ellis, who was working on the precipice of the massive shift to digital photography, used analogue film to prefigure the kinds of manipulation that this new technology would come to easily allow. Ellis’s father, Thomas Ellis, who died before his son was born, had been an avid photographer. When the younger Ellis was in art school, his mother gave him a trove of his father’s negatives, which he then turned to as the source material for an innovative process he developed. Using plaster sculptural forms onto which he projected his father’s negatives, Ellis produced a body of work that includes Untitled (Street Scene) (1987), in which he manipulated these images of the near-past—attempting to replicate something that is always just out of his grasp. The distortions and misregistration of this process seems to describe memory, itself an agent of time, and its spectacular capacity to warp and delete.

Hasbun similarly manipulates family photographs to try and visualize the experience of a lost past and distorted memory. She draws on her diasporic family history in her series Santos y sombras / Saints and Shadows (c. 1991–97). Born and raised in El Salvador, Hasbun is the daughter of Palestinian Christian and European Jewish immigrants. Generations of her family, Hasbun included, were exiled by war. The series includes family photographs and documents, dating back generations and across continents, which Hasbun then layers with her own, new images in order to create poetic, dreamy works that reflect the way that family stories are passed down. As she has said: “My photographic work . . . is a process of re-encounter, of synthesis, and of re-creation. Through it, past and present become interlaced in a renewed configuration; the Palestinian desert and Eastern European ash sift, shift and blend in the volcanic sands of El Salvador, to form the texture of the path on which I define and express my experience.”“Santos y sombras | Saints and Shadows,” Muriel Hasbun, accessed November 22, 2022.

A descendent of both the Ho-Chunk Nation and the Pechanga Band of Luiseño Indians, Hopinka draws on his personal identity and familial relationships to create a distancing effect from his source material, obscuring and removing the specificity of where his landscape photographs were made. His connection to various geographies and their shifting identifications through colonization informs how he explores the landscape through photograph and film in his work. For the series The Land Describes Itself (2019), he used his own photographs of landscapes in the Pacific Northwest, the Southwest, and the Great Lakes. Hopinka then layered this personal archive of images of “homelands of me and many different peoples, containing histories of many more” on a lightbox and photographed so that, in their recombination, they obscure while also creating a new, imagined space.

These three strands of approach—process, performance, and archive—are of course not as distinct as I have implied here. Our various techniques of managing time by breaking it down into comprehensible units imposes a kind of grammar on time. Yet the experience of time that these artists are reaching toward is more complex and more multivalent—it reaches past language. As a whole, the works included in this exhibition are acts of resistance. They push against the contemporary forces of their medium and reject revelation and conclusion. They challenge the limits of their materials. They are not intended to be all-revealing, nor didactic visualizations of alternative models to linear time; they veil as much as they describe.