Balancing Acts

In the early 1980s, two decades into a career that has now spanned over sixty years, the artist Dorothea Rockburne began a series of stacked, shaped canvases. With these abstract compositions she aimed to “conceive of different dimensions,” and to investigate perspective in ways that pushed beyond the concept of painting as a flat space that offers a window into the three-dimensional world. While Rockburne had previously explored folding paper and linen surfaces to produce mathematically proportioned compositions, with this project she envisioned “an imagined, yet in a sense, actual transparency from [the] front canvas through to the back canvas.”Dorothea Rockburne, [artist’s statement], in Dorothea Rockburne: In My Mind’s Eye, by Alicia G. Longwell (Southampton, NY: Parrish Art Museum, 2011), 66.

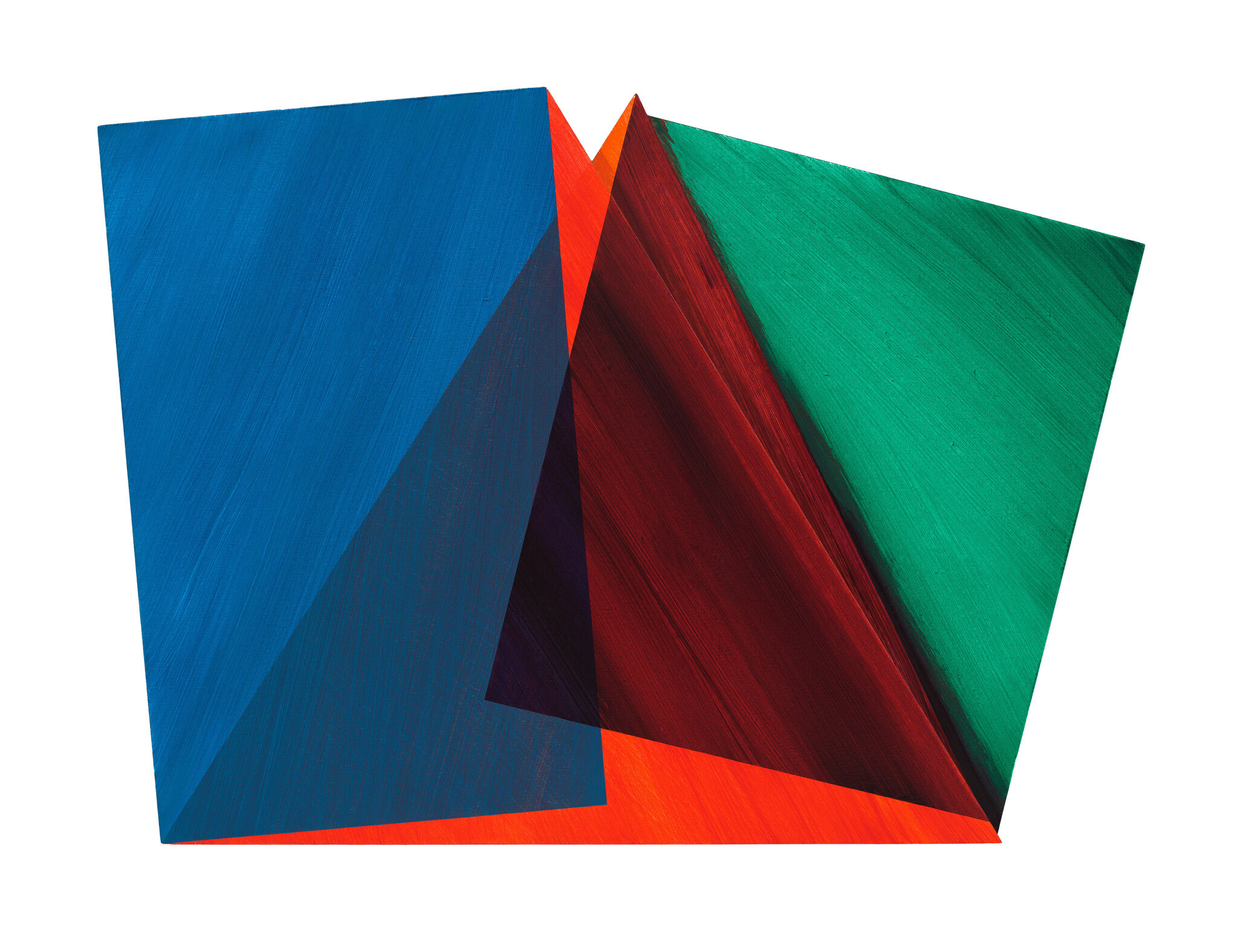

The exhibition In the Balance: Between Painting and Sculpture, 1965–1985, which brings together twelve predominantly abstract works from the Whitney’s collection that span this twenty-year period, takes its title from one such Rockburne painting, Balance, from 1985.

The painted geometries (the blue rectangle, red triangles, and green square) of this work, whose title calls attention to the interplay between the artwork’s surface and substrate, are formed and informed by the shapes beneath them—a pair of irregular polygons, one overlapping the other and positioned in opposite directions. Balance creates a sense of harmoniousness, an effect derived from a desire for an equilibrium between what we can perceive and what we assume, what our brain fills in about how the composition was made. Sustained looking reveals that the translucently applied paint and the dimensionality of the canvases counterpoise each other; they need each other, and they have something to offer each other.

The interplay at work in Rockburne’s painting has a companion in a very different object, one conceived twenty years earlier: Judy Chicago’s Trinity, a three-part, painted sculpture from 1965 that was reimagined in 2019 as Trinity (Outdoor Version). Among the earliest works of Chicago’s career, Trinity is a total abstraction through which the artist explored repeating constructed geometric forms with uniformly applied colors.

Initially made from plywood that was covered with canvas and then spray-painted (a technique Chicago learned in auto body school), Trinity offers two interrelated explorations of gradation through both the increasing (or decreasing) size of the triangular forms and in the subtly changing shades (light to dark or dark to light) of closely related colors. These shifts—elements that are bigger or smaller, shades that are lighter or darker—cohere expressly because they operate in relationship with one another.See Jenni Sorkin, “Minimal/Liminal: Judy Chicago and Minimalism,” in Judy Chicago: Minimalism, 1965–1973 (Santa Fe, NM: LewAllen Contemporary, 2004), 2–16. By the early 1970s, Chicago turned toward more explicitly feminist iconography and other narrative forms.

Balance and Trinity (Outdoor Version)—both important recent acquisitions on view in the Whitney’s galleries for the first time—suggest that the seemingly distinct modes of painting and sculpture of the twenty-year timespan between the works’ creation in fact had a lot to offer each other: painters utilized supports, whether shaped canvases, the wall, or the floor, to deepen the possibilities of their medium, while sculptors took seriously the optical effects of color and surface. Exploring what is exchanged “between” painting and sculpture is not simply to slot these works into prevailing art historical categorizations of this period (geometric abstraction, minimalism, post-minimalism, process art, and feminist art are all movements that can provide context for the works gathered here). Instead, this essay and the exhibition it accompanies follow the prompt of Rockburne’s title and argue that the reciprocity among the works can be productively explored through valences of balance itself. Something always hangs in the balance for artists; something is always at stake, whether personally, artistically, or politically. In what follows, I offer four explorations of the term “balance,” each a subtle variation on the others, that can help deepen our understanding of the individual artworks and provide a connective tissue among them.

Balance as Considering Two Sides of Something, or Pondering

The preponderance of painters in this exhibition are deeply engaged in abstraction, a mode that by the mid-1960s was well-worn, deeply theorized, and even considered by some critics to be overdone (and therefore no longer radical). The prevailing discourse turned its attention to newer experimental practices, including those informed by performance, video technologies, conceptual frameworks, or media culture—approaches with which several of the artists in this exhibition were also explicitly involved.Katy Siegel advocates for this era of overlooked, experimental abstract painting in “Another History Is Possible,” High Times, Hard Times: New York Painting, 1967–1975, ed. Katy Siegel (New York: D.A.P./Distributed Art Publishers), 29–91.Despite this shifting terrain, abstract painting still felt alive to many artists, who remained deeply engaged in its possibilities and even pulled from the techniques and concerns of newer forms of making, resulting in reference-laden, nonrepresentational art. Artists such as Lynda Benglis, Alma Thomas, and Tishan Tsu have questioned how abstraction might offer other ways of seeing the world.

Benglis’s Contraband (1969) serves as a telling example of this moment, as she later reflected: “I wasn’t breaking away from painting but trying to redefine what it was. I was also getting away from stain painting and the grain of the canvas, because they made the process too legible. I wasn’t interested in that, I was interested in illusion.”Lynda Benglis, “Artist’s Statement,” interview by Katy Siegel, in Siegel, High Times, Hard Times, 131.The swirling results of this so-called “spilled” painting is often discussed in terms of how it was made (Benglis opened large containers of colorful liquid latex and poured the contents onto the floor) instead of the ideas the artist aimed to further. Contraband is dense with references to the body, nature, mediated images, and personal history. “I thought about bodily emissions, blood, Vietnam, maps, seeing the Earth from space, the edges of land formations, cloud formations, weather, oil slicks on water, the bayou of Louisiana,” she explained.Benglis, quoted in Kirsten Swenson, review of Lynda Benglis, ed. Caroline Hancock, Franck Gautherot, and Seung-Duk Kim, caa.reviews (December 1, 2011), 10.3202/caa.reviews.2011.135.

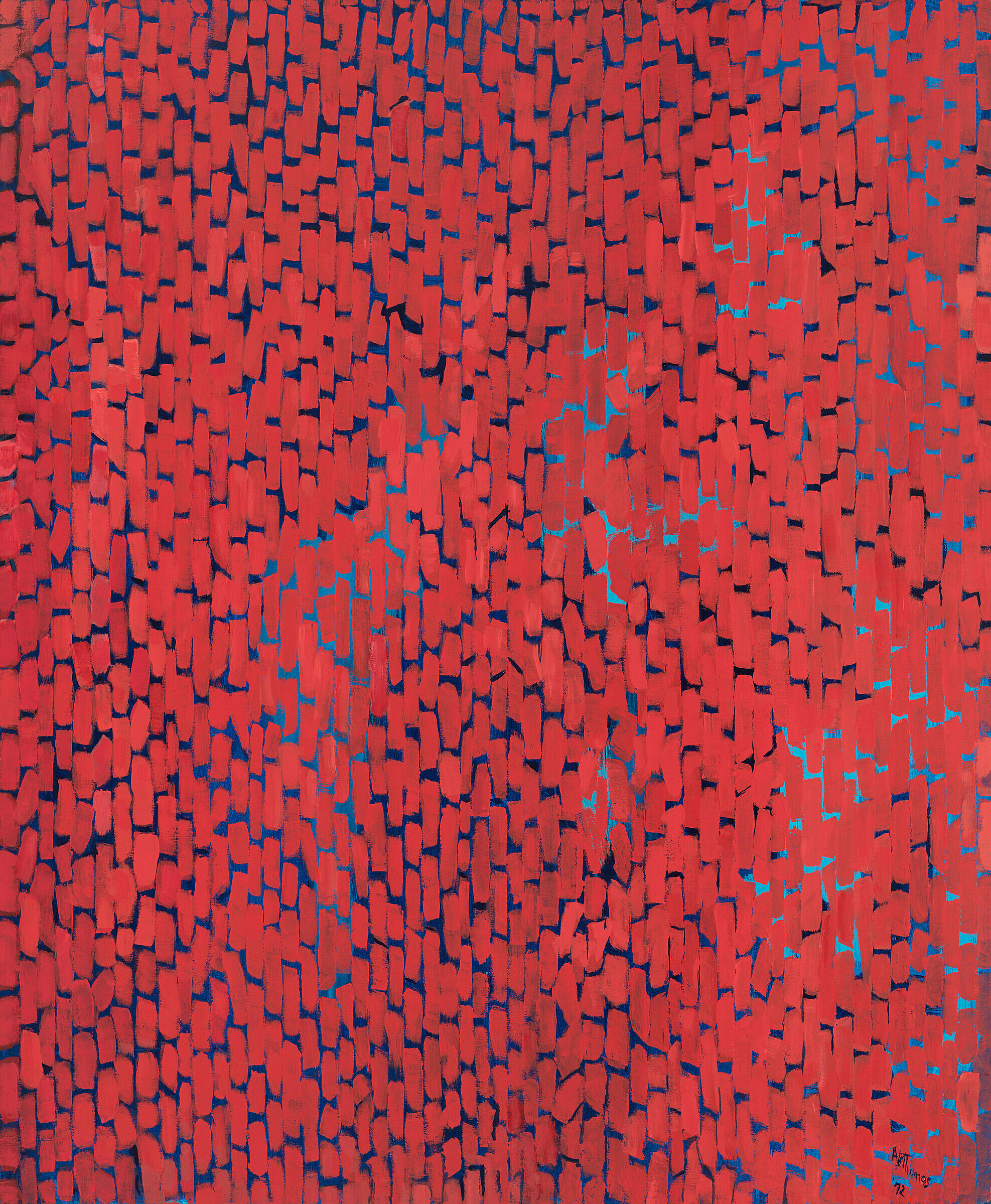

Thomas similarly converted her interest in the natural world (sources included flowers, gardens, and outer space) into colorful, abstract marks. In Mars Dust (1972), she interpreted NASA mission photographs of dust storms on Mars as repeating rectangular forms that rely on the interplay of positive and negative space. The compositional elements, which can be understood as depictions of dust (the red marks, the matter) suspended in outer space (the blue marks, the vastness of the solar system), are here rendered in terms of each other.

Many artists working in the decades spanning 1965 to 1985 shared Thomas’s fascination with the linkage between nature (in this instance space itself) and culture (here represented by scientists’ images of space). For Hsu, paintings such as Outer Banks of Memory (1984) are broadly concerned with technology, the shifting terrain of screen culture, and the topographies of media-saturated minds. His works restlessly seesaw between painting and dimensional objects on the wall, between organic forms and technological ones that help us see multiple perspectives in greater depth.

Literal Balance, or Seeking Equilibrium

Artists engaged in geometric abstraction or repetition of form, including Alvin Loving, Freddy Rodríguez, and Mary Ann Unger, reveal the precariousness of pursuing balance: once achieved, can it be maintained?

In paintings such as Rational Irrationalism (1969), which depicts a set of interlocking, open cubes defined both by painted lines and by the boundaries of two shaped canvases, Loving demonstrated his engagement with sculptural concerns on painterly terms. He sought, in his words, “to make something that appeared three-dimensional, but couldn’t be built” and to think “about color as viable structure.”Alvin Loving, “Alvin Loving: Interview,” by Beryl White, The Appropriate Object: Maren Hassinger, Richard Hunt, Oliver Jackson, Alvin Loving, Betye Saar, Raymond Saunders, John Scott (Buffalo, NY: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, 1989), 45; and Loving, quoted in Frank Bowling, “It’s Not Enough to Say ‘Black Is Beautiful,’” Art News 70, no. 2 (April 1971): 84.Despite the immediate critical attention paid to the geometric rigor of this and similar paintings, Loving quickly felt “boxed in,” knocked off balance.In 1969 Loving became the first Black man to have a solo exhibition at the Whitney (Alvin Loving, December 19, 1969–January 25, 1970), the direct result of organizing efforts led by the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, whose members, including Benny Andrews and Henri Ghent, pressured the museum to vastly increase the inclusion of Black artists in their exhibition programming.By 1971, after seeing the exhibition Abstract Design in American Quilts at the Whitney, he cut up existing paintings into diamond shapes, learned to sew, and pieced the remnants of his former works into new flowing, unstretched constructions.See, for example, Loving’s Brownie, Sunny, Dave, and Al (1972) in the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC.

Rodríguez’s Y me quedé sin nombre (And I ran out of names) from 1974 features three striped, hard-edge polygons, stacked vertically. Although they are balanced one on top of the other, the forms—evocative of a body temporarily stilled—suggest instability. Likewise, the crispness of the artist’s painterly technique is visually distinct from the disequilibrium of a life interrupted by political turmoil in the Dominican Republic, from where the artist moved to the United States in 1963, at age eighteen. Rodríguez has reflected that geometric abstraction in particular offered him a way to channel internal calm: “You cannot drink a pint and then you start doing geometric paintings.”Freddy Rodríguez, “Artist Freddy Rodríguez in Conversation with Curator and Art Historian Dr. E. Carmen Ramos,” 2015, video, 4:59–5:03.

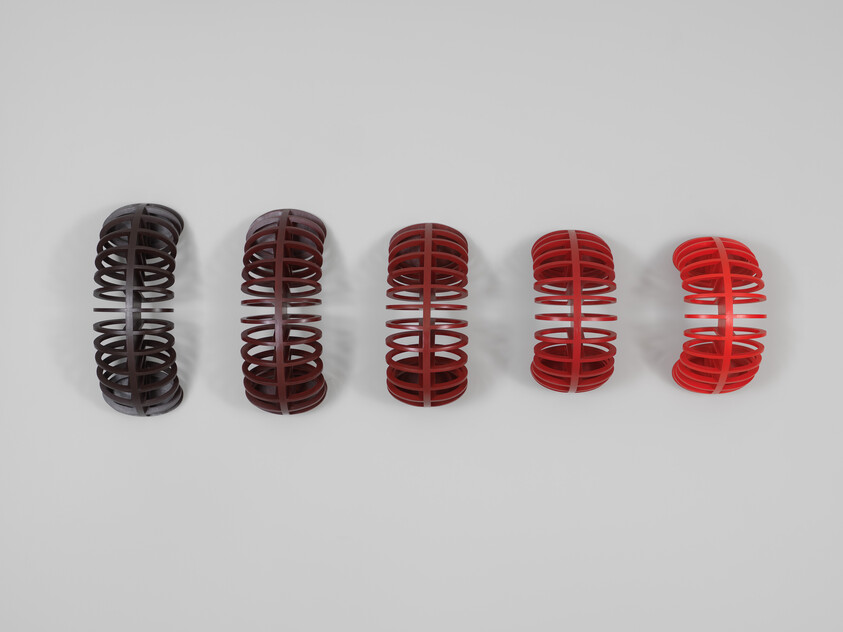

This practical quip offers a reminder that imbalance is always close at hand, a state of being that Unger echoes in her Vertebrae series from the early 1980s. Inspired by the physical and psychological experience of pregnancy, Unger hand-sanded jigsaw-cut plywood constructions and painted them in bright, acrylic colors. Their shapes evoke spines, ribcages, and the bodily changes required for building new human beings; the surprising bendability of plywood is akin to corporeal elasticity.

In Red Vertebrae (1980), the tonal gradations perhaps suggest the passage of time, as the body seeks an ultimately impossible equilibrium between a previously existing and newly forming life.See Horace D. Ballard, ed., Mary Ann Unger: To Shape a Moon from Bone (Williamstown, MA: Williams College Museum of Art, 2022), 37–38.For Water Spout (1980–81), Unger positioned three nestling, curved forms between the wall and the floor. In their dependency on those architectural elements, they evoke the precarious interdependence of family units.

Making Up for (Lost Time)/Balancing Out

Many of the women artists featured in this exhibition—including Thomas, Edna Andrade, and Kay WalkingStick—share a common refrain: the struggle to maintain their artistic aspirations amid familial and professional obligations and societal limitations. Thomas turned to abstraction in the late 1950s, only a few years prior to retiring from teaching at a junior high school in Washington, DC (where she had studied at Howard University and was active in the local art scene), after thirty-five years of working in the same classroom. It was then, at age seventy-one, that her full-time career as an artist began. Her story is often framed by this so-called late start, at times to the point of romanticization. How could someone in her seventies develop a new artistic vocabulary, critics seemed to wonder? As she reflected, “Most everyone is surprised at the way that I paint. And I think that is what has made me outstanding, is my age. And being a woman. They’re surprised that a woman would be that creative at my age.”Alma Thomas, [unidentified broadcast about Alma Thomas including an autobiographical account], Alma Thomas papers, c. 1894–2000, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC. Reproduced in Ian Berry and Lauren Haynes, eds., Alma Thomas (New York: Prestel, 2016), 218.Thomas understood that her stylistic innovations resulted because of, not in spite of, the factors that delayed her critical reception.

Andrade cited numerous influences—including the writings of Josef Albers, folk art, vernacular practices such as quilt making, and ancient sources like tiling and mosaics—that led her to pursue opticality as a primary subject in abstract paintings such as Cool Wave (1974). But she was also refreshingly open about the practical elements behind her stylistic choices: in 1959, when she was forty-two years old, Andrade supported herself by teaching at the Philadelphia Museum College of Art (now the University of the Arts), where she focused on problems of perception in her class assignments. She discovered that due to her schedule she “had a very limited amount of time to work” and felt that she had to “have a programmed way of working. . . . you would have a plan of operation that you could lay out as though you were doing embroidery or something, and pick it up when you have a little bit of time, and not have to be in the state of grace you have to be in if you’re an expressionist painter.”Edna Andrade, oral history interview by Patricia Likos, April 1–29, 1987, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.The need to consider practicality and creativity directly informed Andrade’s artistic output.

In 1973, at the age of thirty-eight and as the mother of two children, Kay WalkingStick went back to school for her master’s degree, commuting to the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn from her home in suburban New Jersey.See Kate Morris, “What Lies Beneath: Sacred Geometries, 1970–83,” in Kay WalkingStick: An American Artist, ed. Kathleen Ash-Milby and David W. Penney (Washington, DC: National Museum of the American Indian, 2015), 56.Soon after, she began a series of paintings of seemingly unassuming aprons suspended from three points as if splayed against a wall.

In Gray Apron (1974) and related works, her subject becomes a stand-in for an invisibilized body. WalkingStick wrote several unpublished short poems inspired by these paintings that elucidate her associations between the garment and the complexity of her multiple roles:

“Love Poem on my Birthday” 3-1-74 the eve of my birthday

Pregnant apron heavy with use,

decadently beautiful in your usedness,

Dirty, but colorful, like a certain middle-aged lady I know.

Although you never hang (around) in a kitchen,

You live in one place and I live in two.

Is it for your perversity or my diversity,

that I love you?Kay WalkingStick, “Love Poem on my Birthday” (unpublished, March 1, 1974), © Kay WalkingStick, reproduced here with permission of the artist.

The ordinary apron becomes a loaded emblem of protection from the mess (literal, psychological) of both domestic and studio life.

These artists’ balancing acts help refute the notion that abstraction is somehow neutral or devoid of gender, and reveal that the lived, bodily experience (for artists, for us all) is a politicized one.

Balance as Assessing the Remainder

Artworks exist in relationship to themselves, to other works, and to the space or site in which they are installed. For this last valence of balance, the interaction of objects with physical space is akin to a bank account. What is left over (the walls, the floors) is just as essential as what is spent (the paintings and sculptures on view).

David Novros has consistently resisted situating his wall-based works, such as his untitled painting from 1969, in direct conversation with sculpture. For Novros, the fiberglass units—each molded into an L shape and coated in various colors of automotive paint—are definitively “wall paintings,” or even “portable murals,” an apt description for an artist deeply invested in fresco. “My strategies,” he explained, “came by way of making shapes that would move along a wall, and allow a viewer to move along the wall. So you’re having kind of a kinesthetic experience, not simply standing in front of a rectangle waiting for it to do something to you.”David Novros, oral history interview with Michael Brennan, October 22–27, 2008, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.The wall has a crucial part to play. It is not simply the place where the painting hangs; its support allows the painted forms to lead the viewer through the physical space of the gallery.

Jane Kaufman’s Untitled of 1969 consists of shaped canvases in two parts that are to be installed one above the other with a strip of blank wall left visible in between them. The barely perceptible, subtle modulations of sprayed pastel colors shift as the viewer’s eye travels across the canvases’ undulating surfaces. The optical outcome is atmospheric; visual fields that are both decidedly present and on the verge of disappearing call attention to the wall on which the canvases hang, or even seemingly float along. Kaufman offered little direct commentary on this and related works, insisting only that her paintings are not objects but rather “states of being.”Jane Kaufman, quoted in Marcia Tucker, Jane Kaufman: Recent Paintings (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1971), n.p.They are not this specific thing, but not its lack or absence, either. Instead, Kaufman asks us to experience what she has made and also what remains in between and all around them.

The balancing acts on display in these works—grouped here under the loose definitions of pondering two sides, seeking equilibrium, making up for lost time, and assessing what remains—gesture toward how we might consider artworks of this twenty-year period in ways other than as part of entrenched historical accounts. In doing so, it becomes apparent there is more in the balance to consider.