Teacher Guide:

2015 The Whitney’s Collection

Sep 28, 2015

Dear Teachers,

We are delighted to welcome you to the exhibition, The Whitney’s Collection, on view at the Museum through April 4, 2016. The exhibition represents selections from the Museum’s collection that trace the development of American modernism from 1912 to the mid-1960s.

The art on view elaborates some of the themes, ideas, beliefs, and passions that have galvanized American artists in their struggle to work within and against established conventions, often directly engaging their political and social contexts.

This teacher guide provides a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offers suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts.

We look forward to welcoming you and your students at the Museum.

Enjoy your visit!

The School and Educator Programs team at the Whitney

THE WHITNEY’S COLLECTION

Since the Whitney Museum first opened its doors in 1931, the collection has grown to more than 22,000 objects. The approximately one hundred works from the Whitney’s collection on view in this exhibition range in date from 1912 to 1965. Works of art across all mediums are displayed together, acknowledging the ways in which artists have engaged various modes of production and dissolved the boundaries between them. The presentation also underscores the difficulty of neatly defining the country’s ethos and inhabitants, a challenge that lies at the heart of the Museum’s commitment to and continually evolving understanding of American art.

Pre-visit Activities

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the exhibition. You may want to introduce students to at least one or two works of art in the exhibition. See the Images and Related Information section of this guide for examples of works that may have particular relevance to your classroom.

Objectives:

- Introduce students to the works of American artists and examine how they represented the world around them.

- Introduce students to the themes they may encounter on their museum visit.

- Explore how artists have interpreted America.

Artist as Observer

EARLY SUNDAY MORNING

a. View and discuss Hopper’s painting, Early Sunday Morning, 1930. Ask your students to imagine they are walking down the street in the painting. What do they notice? Where do they think this street might be? Why? What time of day do they think it is? How can they tell?

b. Writer John Stone wrote an evocative poem about Edward Hopper’s iconic painting, Early Sunday Morning, 1930. Read the poem with your students and compare their observations and thoughts about the painting with Stone’s. What did students notice about the painting that is different from Stone’s view?

http://english.emory.edu/classes/paintings&poems/sunday.html

c. Before making his paintings, Hopper started off with sketches. In his studio he combined them, often adding added things from his own imagination. For Hopper, it was more important to capture a feeling or mood than to represent the world exactly as it looked. What kind of mood do your students think he is expressing here? Ask your students to brainstorm words to describe the scene and the mood it evokes for them. Write the words on a board or “word wall.”

d. Have students think of their favorite street or place at a certain time of day or night. Ask them to come up with ten descriptive words for this place and write a short poem using their selected words.

ARTIST AS STORYTELLER

DEMPSEY AND FIRPO

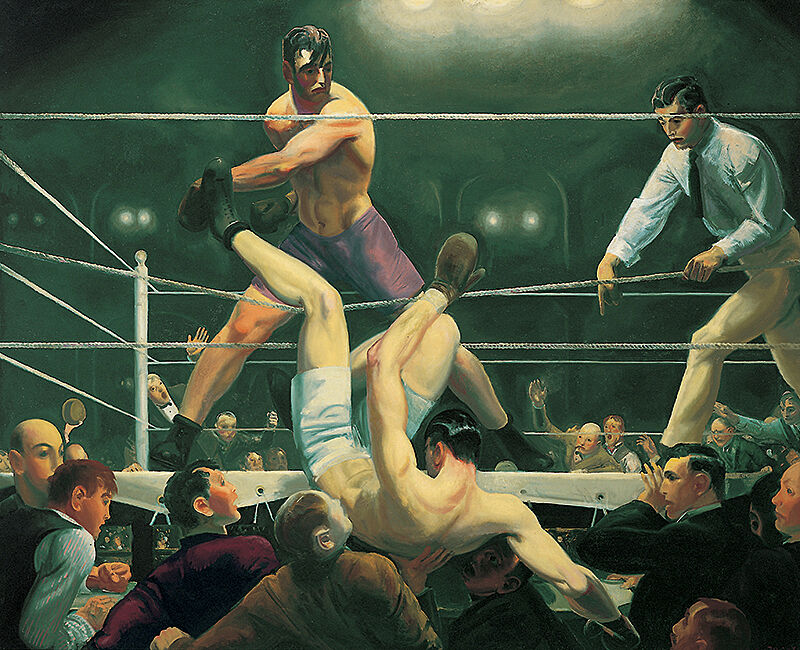

a. With your students, view and discuss George Bellows’s painting Dempsey and Firpo, 1924. Ask students to describe what is happening in this work. Where would they be if they were in the space of this painting? Have students follow the lines made by the people’s bodies and ropes. Where do they go? What shapes can they find when they follow the lines? Notice the absence of women in this scene, according to social conventions of the time.

b. Ask your students to create a narrative or story around the image. What is going on? What might have happened before the moment depicted? What might happen afterwards?

c. Watch historical film footage of Dempsey vs. Firpo, 1923: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9NN0vGHnCLo

How does the film differ from the painting? Is it similar? In what ways?

d. Ask students to think of a recent sports or entertainment event that they find interesting. For example, a concert, a performance, a football match, a television show, or a movie. Have them create a drawing or collage depicting one exciting moment of that event. Ask them to consider the following questions. What makes that moment exciting? How will they show the excitement of that moment? Whose point of view will they represent? Are students watching this event or are they involved as one of the players or characters? What details will they add so people know what the event is?

ARTIST AS STORYTELLER

THE ARTIST AND HIS MOTHER

a. Ask your students to look closely at Arshile Gorky’s painting, The Artist and His Mother, 1926-c.1936. Let them know that the painting is based on a photograph of Gorky and his mother from 1912. Gorky’s mother starved to death in 1919, during the Armenian genocide, and the next year, Gorky arrived in the United States as a refugee. The photograph was the only image of his mother that Gorky had, and therefore it was a treasured memory. The photograph can be found here: http://calitreview.com/5339/arshile-gorky-a-retrospective-at-the-philadelphia-museum-of-art/ Ask students to compare the painting with the photograph. What similarities and differences do they notice?

b. Ask your students to think of someone in their family or a close friend (who is not in the same class). Have them describe their features and clothing, a few objects, and a place they associate with that person. Have students make a drawing from memory or write a description of the person they selected.

c. Ask students to present and discuss their drawings or written descriptions. What did they find easy to remember? What was difficult to recall? Why? How did students choose to represent the person?

Post-visit Activities

Objectives

- Enable students to reflect upon and discuss some of the ideas and themes from the exhibition.

- Have students further explore some of the artist’s ideas through discussion and art-making activities.

Museum Visit Reflection

After your museum visit, ask students to take a few minutes to write about their experience. What new ideas did the exhibition give them? How did the exhibition change their ideas about what a painting can be? What other questions do they have? Ask students to share their thoughts with the class.

Artist as Observer

INSPIRATIONAL ARCHITECTURE

Artists Elsie Driggs and Joseph Stella were (respectively) inspired by steel mills in Pittsburgh and the Brooklyn Bridge—both architectural structures that were built for specific purposes and had particular effects on their surroundings. Ask your students to compare and discuss the paintings. How do the artists represent these structures? Why do students think the artists chose to paint these structures? Which parts were they most drawn to? What shapes, lines, and colors did they use to represent these parts?

a. Ask your students to take photographs or make drawings of a building or architectural structure that they admire in their city, town, or neighborhood. For example, a public building, a skyscraper, a bridge, a factory, or a house. If possible, have students research their selected site, including its history and original purpose.

b. Ask students to present and discuss their photographs, drawings, and findings. What did students choose to depict? Why? What did they discover about their selected sites? What are these buildings or structures used for today? What effect do they have on their surroundings? On people?

Artist as Experimenter

THE CIRCUS

a. Review & discuss calder’s Circus, 1926-31. Watch videos of calder performing his circus here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C8To4mp9HVw. Ask students to carefully observe how calder makes the circus characters move.

b. Ask your students to create their own wire sculptures. Have them consider how they can make parts move, rock, or swing, by bending, curling, twisting, and hooking the wire.

Artist as Experimenter

Abstraction

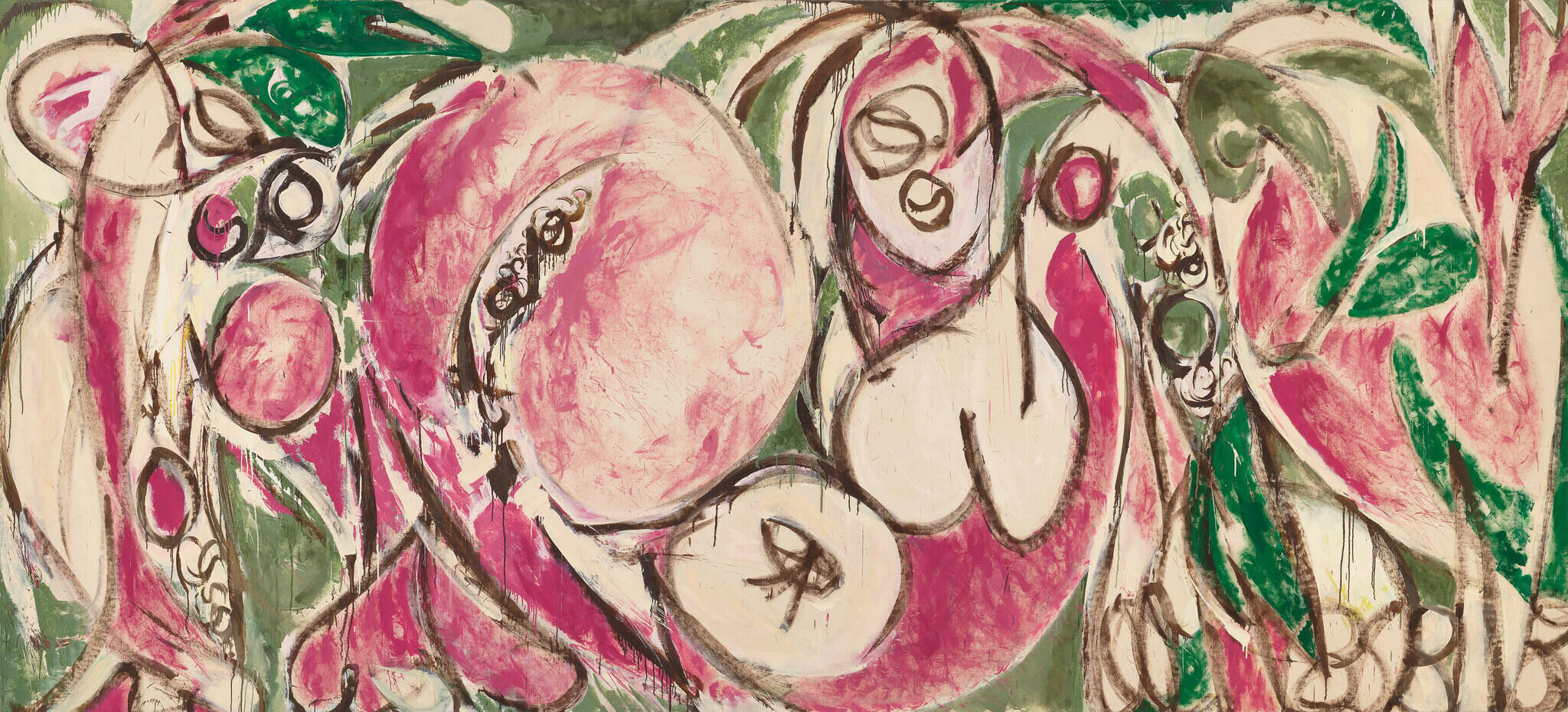

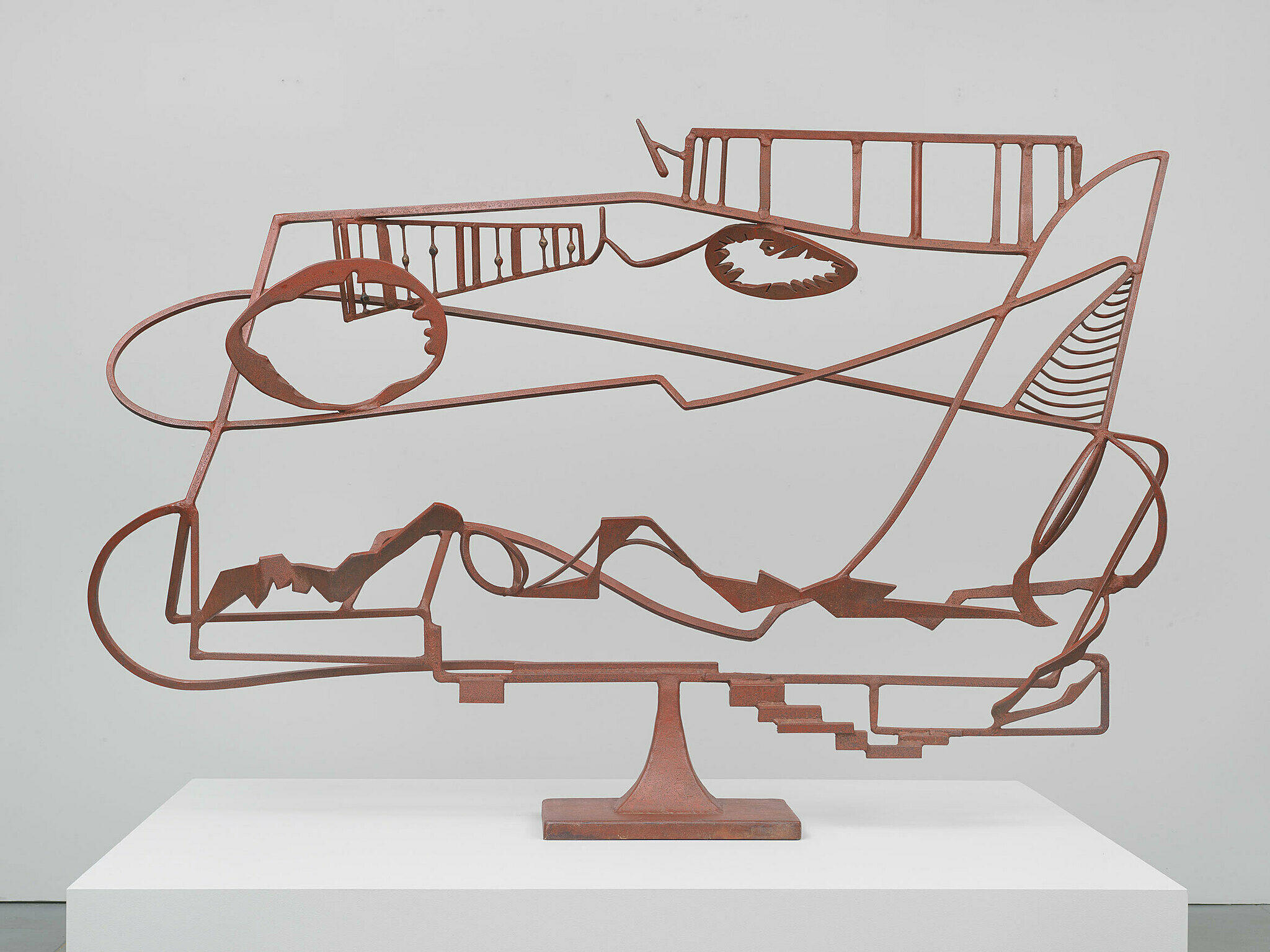

a. In The Seasons, 1957, Lee Krasner used abstract organic and plant forms to represent the cycles of nature. For Hudson River Landscape, 1951, David Smith welded pieces of found steel together, often maintaining their original shape and using their abstract forms to represent parts of the landscape, mountains, or train tracks along the river. Ask your students to look closely at these works. Can students identify shapes that might represent elements of nature or landscape?

b. Ask your students to think of a journey that they often make, such as to school, or to their home. Ask students to draw four different things they remember from that journey. Have them include both natural and manmade forms. Have students use simple outlines and shapes from their sketches and combine them into one drawing. Display and review students’ drawings. How did they combine their shapes?

Images and Related Information

GEORGE BELLOWS

DEMPSEY AND FIRPO, 1924

Dempsey and Firpo captures a dramatic moment in the September 14, 1923, prizefight between American heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey and his Argentine rival Luis Angel Firpo. Looking up from this composition’s low vantage point, we find ourselves among the spectators—including the artist, George Bellows, who inserted his own likeness as the balding man at the far left. Although Dempsey was the eventual victor, the artist chose to represent Firpo knocking his opponent out of the ring with a tremendous blow to the jaw. Bellows heightened the excitement of the fight by bathing the boxers in a lurid light and capturing the dark, smoke-filled atmosphere around the ring.

ALEXANDER calder

calder’S CIRCUS, 1926-31

Alexander calder originally trained as a mechanical engineer, but he was working as a newspaper illustrator in New York in 1925 when he was sent to make sketches of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus. His visit to the circus sparked a lifelong interest. When he moved to Paris in 1926, he began calder’s Circus, crafting dozens of small movable figures and props from wire and found objects. Adding acts over several years and transporting the miniature circus in several suitcases, he gave performances in his studios and at the homes of friends. calder acted as both stagehand and impresario: he constructed makeshift bleachers from wood crates and planks, handed out cymbals and other noisemakers, and cued up records on his gramophone. Narrating the acts in English and French, he manipulated acrobats, a bearded lady, a lion tamer and his lion, and other figures.

ELSIE DRIGGS

PITTSBURGH, 1927

Elsie Driggs was inspired to make this painting by a childhood memory of Pittsburgh’s steel mills. Returning twenty years later to capture the scene, she initially tried to paint it from inside the mills. But the owners thought the factory floor was no place for a woman, and management worried that she might be a labor agitator or industrial spy.

As much as the painting may seem to viewers today to be a warning about the dangers of industrial pollution, Driggs had no oppositional agenda. She ended up basing the work on drawings she made from a hill above her boardinghouse, later writing that she stared at the mills and told herself: “‘This shouldn’t be beautiful. But it is.’ And it was all I had, so I drew it.”

ARSHILE GORKY

THE ARTIST AND HIS MOTHER, 1926-C.1936

Arshile Gorky based this portrait of himself and his mother on a photograph taken in Armenia in 1912, when he was eight years old. His mother died in 1919 after years of deprivation during the Turkish Ottoman Empire’s ethnic cleansing of the Armenian population. The following year, Gorky arrived in the United States as a refugee of the genocide. As he established his career as an artist in his new homeland, he remained preoccupied with the photograph; it offered a potent symbol of a tragedy that had killed between one million and one and a half million Armenians. Gorky’s painting, made over a span of ten years, is not a precise replica of the camera’s image. Instead, he worked in broad areas of color and used dry brushwork to create a soft, blurred effect. He furthered this quality by leaving the hands undefined, at once suggesting the loss of physical connection between him and his mother and the fading of memories over time.

Edward Hopper

EARLY SUNDAY MORNING, 1930

Edward Hopper described Early Sunday Morning as “almost a literal translation of Seventh Avenue,” but he left out many of the street’s details, making it difficult to identify as a New York City thoroughfare. The lettering in the signs is illegible and human presence is merely suggested by the variously arranged curtains adorning the windows of the second floor apartments. The long early morning shadows in the painting never appear on Seventh Avenue, which runs north-south. Yet these very contrasts of light and shadow, coupled with the composition’s series of verticals and horizontals, create the charged, almost theatrical atmosphere of an empty street at the beginning of the day.

LEE KRASNER

THE SEASONS, 1957

In The Seasons, Lee Krasner combined a traditional subject with a modern pictorial form, the all-over composition. Historically, the subject of the four seasons has offered artists the opportunity for allegorical meditations on the life cycle. Krasner’s version exemplifies the regenerative portion of that cycle, with boldly, almost garishly colored plant forms. This monumental painting offered Krasner an outlet during a time of deep personal sorrow. The year before, her husband, fellow artist Jackson Pollock, had died in a car accident. In the wake of this sudden loss, Krasner remarked about The Seasons, “the question came up whether one would continue painting at all, and I guess this was my answer.”

DAVID SMITH

HUDSON RIVER LANDSCAPE, 1951

David Smith based Hudson River Landscape on drawings he made while looking out the window on train rides between New York City and his home in Bolton Landing in upstate New York. The open frame, which suggests a window, positions us to look at the sculpture head-on, viewing its thin contour lines as a drawing in space. To make this work, Smith welded together pieces of found steel, often preserving their original shape to show parts of the landscape. He liked welding—a modern industrial process invented in the late nineteenth century—in part because it freed sculpture from the historical burden of such traditional techniques as carving and casting.

JOSEPH STELLA

THE BROOKLYN BRIDGE: VARIATION ON AN OLD THEME, 1939

For Joseph Stella, as for many of his contemporaries, the Brooklyn Bridge was the central icon of American cultural achievement. He first depicted the bridge in 1918 and returned to it throughout his career. Here, Stella portrays the bridge with a linear dynamism borrowed from Italian Futurism. He captures the dizzying height and awesome scale of the bridge from a series of fractured perspectives, combining dramatic views of radiating cables, stone masonry, cityscapes, and night sky. He saw the bridge in religious terms, as a “shrine containing all the efforts of the new civilization of AMERICA—the eloquent meeting of all the forces arising in a superb assertion of their powers, in APOTHEOSIS.” Fittingly, he depicted the bridge as a modern-day altar, its soaring cables and pointed Gothic arches reinforced by his palette of blues, reds, and blacks that alluded to light filtering through a stained-glass window.

Bibliography and links

Miller, Dana, Ed. Whitney Museum of American Art: Handbook of the Collection. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2015.

/exhibitions/the-whitneys-collection

The Whitney’s Collection exhibition information.

The Whitney’s collection.

The Whitney’s programs for teachers, teens, children, and families.

The Whitney’s online resources for K-12 teachers.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9NN0vGHnCLo

Film footage of Dempsey vs. Firpo, 1923.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources and Heather Maxson, Director of School, Youth, and Family Programs.

Education programs in the Laurie M. Tisch Education Center are supported by the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation; The Pierre & Tana Matisse Foundation; Jack and Susan Rudin in honor of Beth Rudin DeWoody; the Barker Welfare Foundation; Con Edison; public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council; and by members of the Whitney’s Education Committee.

Generous endowment support for education programs is provided by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Laurie M. Tisch, Steve Tisch, Krystyna O. Doerfler, Lise and Michael Evans, and Burton P. and Judith B. Resnick.

Free Guided Student Visits for New York City Public and Charter Schools endowed by the Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.

The Whitney’s Education Department was recently the recipient of a National Leadership Grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services.