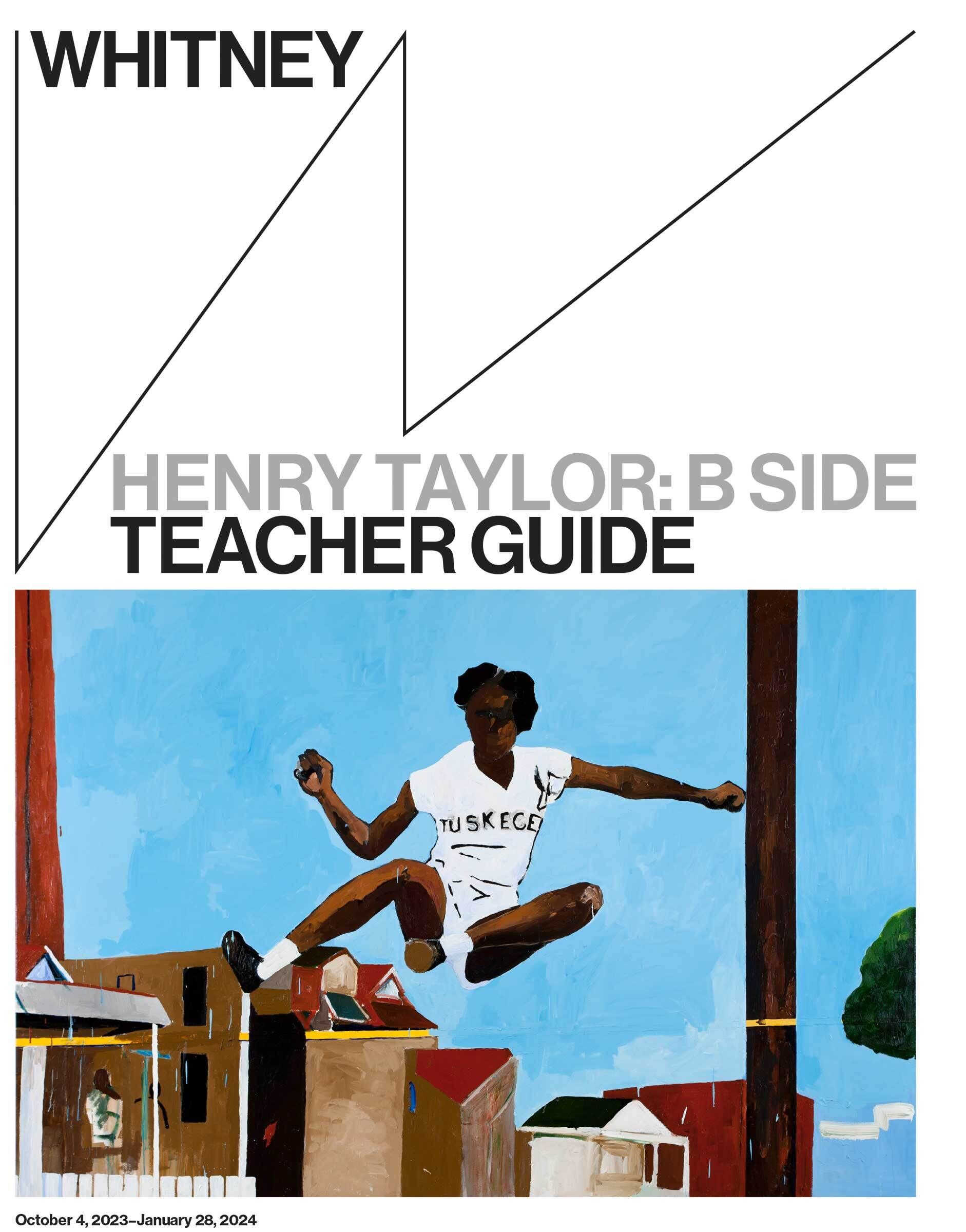

Henry Taylor

1958–

Introduction

Henry Taylor (born 1958) is an American artist and painter who lives and works in Los Angeles, California. He is best known for his acrylic paintings, mixed media sculptures, and installations.

Wikidata identifier

Q18343072

Information from Wikipedia, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License . Accessed February 12, 2026.

Country of birth

United States

Roles

Artist, painter

ULAN identifier

500333777

Names

Henry Taylor

Information from the Getty Research Institute's Union List of Artist Names ® (ULAN), made available under the ODC Attribution License. Accessed February 12, 2026.