She's Thinking about Romance

Harmony Holiday

Related exhibition

The exhibition Henry Taylor: B Side is on view October 4, 2023–January 28, 2024.

Black feminine interiority is often coopted rather garishly by those who need an oversimplified archetype to represent some harrowing blend of strength and servility, or diligence and decadence, or wit and intensity. Black womanhood becomes seductive as a high concept or expedient political accessory, a gloss—whereas actual Black women become regarded as more and more forbidden and mystifying while being denied the comforts and humanity attributed to them by the collective consciousness. On the one hand, this makes Black women magicians; on the other hand, it is a disappearing act. Attempts to revise or call out the misconception that Black women are so strong they don't need tenderness become hyperbolic, fawning, and phony. We are left to deal with both the problematic myth and the backlash of shattering it.

Romance is the only intervention we have not explored in our attempts to navigate the experiences of Black women. What if they possess romantic inner lives, uncomplicated by bitterness or rage, benevolence or tenacity, scandal or paranoia? Henry Taylor gives us occasion to envision Black romanticism. His yellow cap sunday (2016) conjures the image of a Black woman alone wearing a shade of yellow that resembles muted autumnal sunlight as dusk approaches and the sky flickers in the auburn trees; she's in a forest-green landscape that acts like a score, making her the center of a love song. Her skin is perfect, the deepening base her sunny garments are eager to adorn and reflect, and her expression is tart and skeptical. She's on the verge of either a grin or a sneer, as if taking in a shady sermon and awaiting its punchline, waiting to be rescued from another false prophet. She's a little entitled in her ambivalence, looking away moodily, not to contrive a rumor or piece of gossip about her surroundings, but to avoid becoming one. She looks away to retreat into herself, to take a moment to worship her own manner of thinking, or to recall it as armor against whatever she's hearing and seeing in her current role as a muse. She is thinking about romance, about being swept away from the mundane and into a dream sequence. She is the embodiment of romance, with a beauty that resents the attention it commands because staring and dissecting are the opposite of understanding.

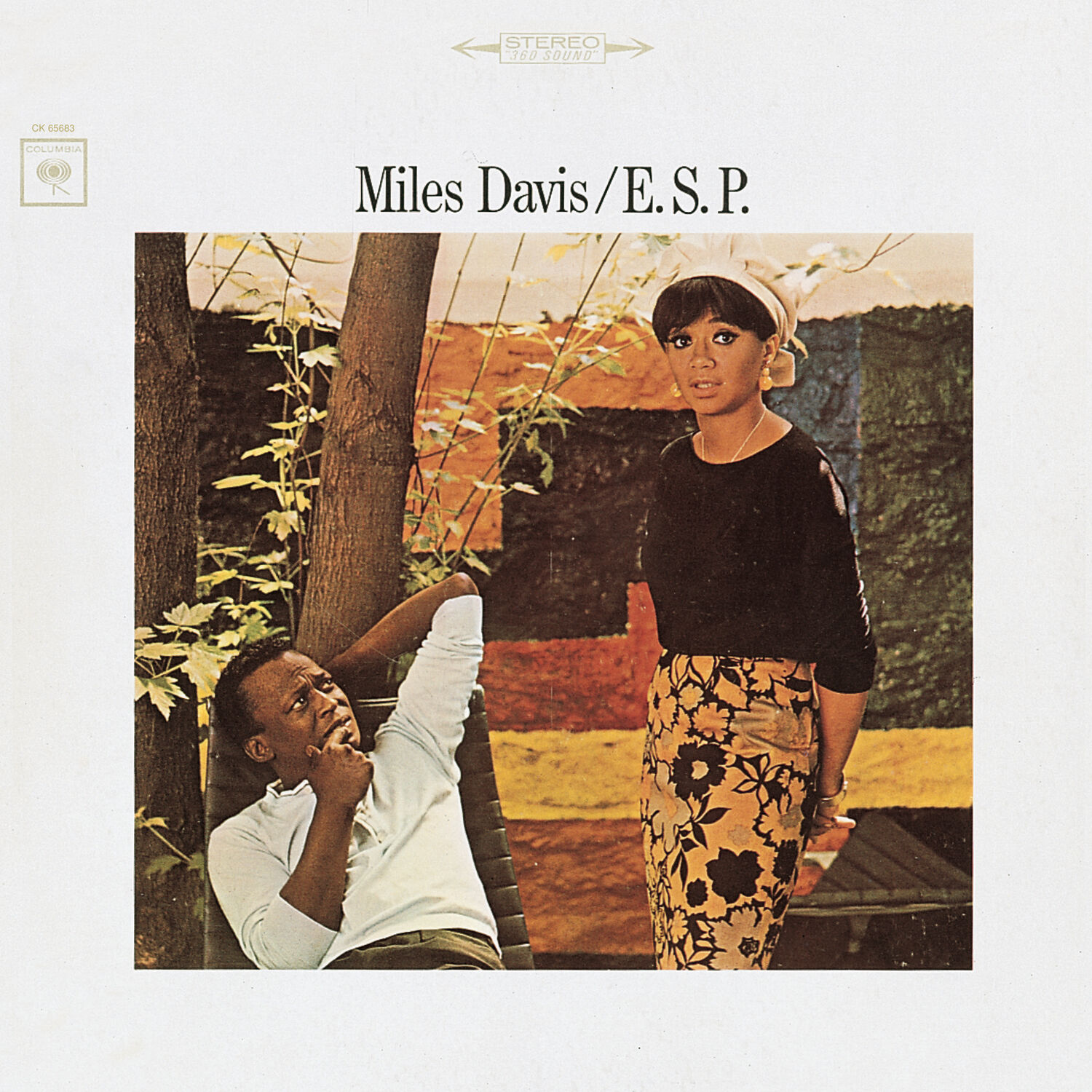

To understand her you would have to be far less concerned with her image; you would have to know what's behind her eyes so intently that you become Miles Davis and compose the song "Mood" (1965) from his album E.S.P., tiptoeing into the mind of an object of desire and embracing every demon there. His then-wife Frances is pictured on the cover of E.S.P. with him, wearing black and yellow and a vaguely forced expression. He stares at her, desperate for a way inside as she gazes directly at the camera. The photograph was taken the day before she ran out of the house naked to escape one of his beatings and never returned. She loved him and he loved her—at the beginning it was romantic, and sometimes even terrible endings grow romantic in hindsight, the pain and wounds becoming attached to the ego and objectified like movie scenes. They almost forget the reality of it while the drama of chase and charge take over until they are characters in their own lived past, the Black woman's romance offered and revoked by the same scene, the same song, and the same long yellow stroke blotched with streaks and screeches, moans, giggles, and screams.

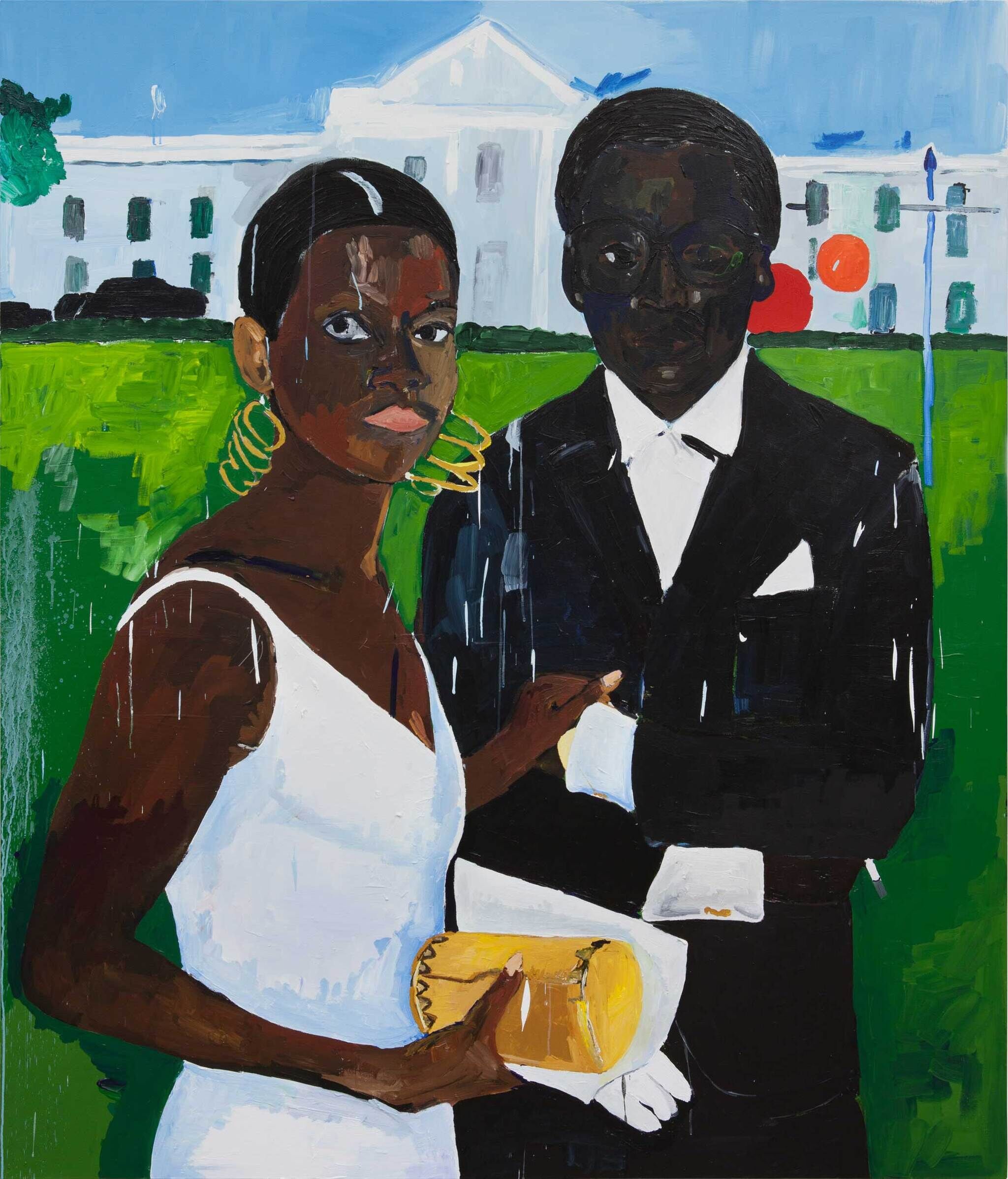

Taylor's painting, Cicely and Miles Visit the Obamas (2017) enters the next phase of Black romance—redemption. Cicely Tyson grips a yellow spherical purse and looks nervous and a little frigid, guarding her man and her own poise. Miles Davis appears vulnerable and reluctant, arms crossed, deliberately unreachable with clenched fists; Cicely awkwardly holds his cuff to express their union. It's solemn Black romanticism, cold but eternal and a little militant about itself. Returning to yellow cap sunday we realize that the woman in the painting could be a version of Frances or Cicely, looking away from the man she loves, or the God she loves in an effort to salvage some romance between them in a world that asks her to pretend that she doesn't need fantasies. Do we still want a Sunday kind of love?

The artworks referenced here are not included in the Whitney's presentation of Henry Taylor: B Side.

This essay is republished from the exhibition catalogue, Henry Taylor: B Side.