High Pressure Repairs: Restoring the Player Piano for Conlon Nancarrow

Jun 27, 2015

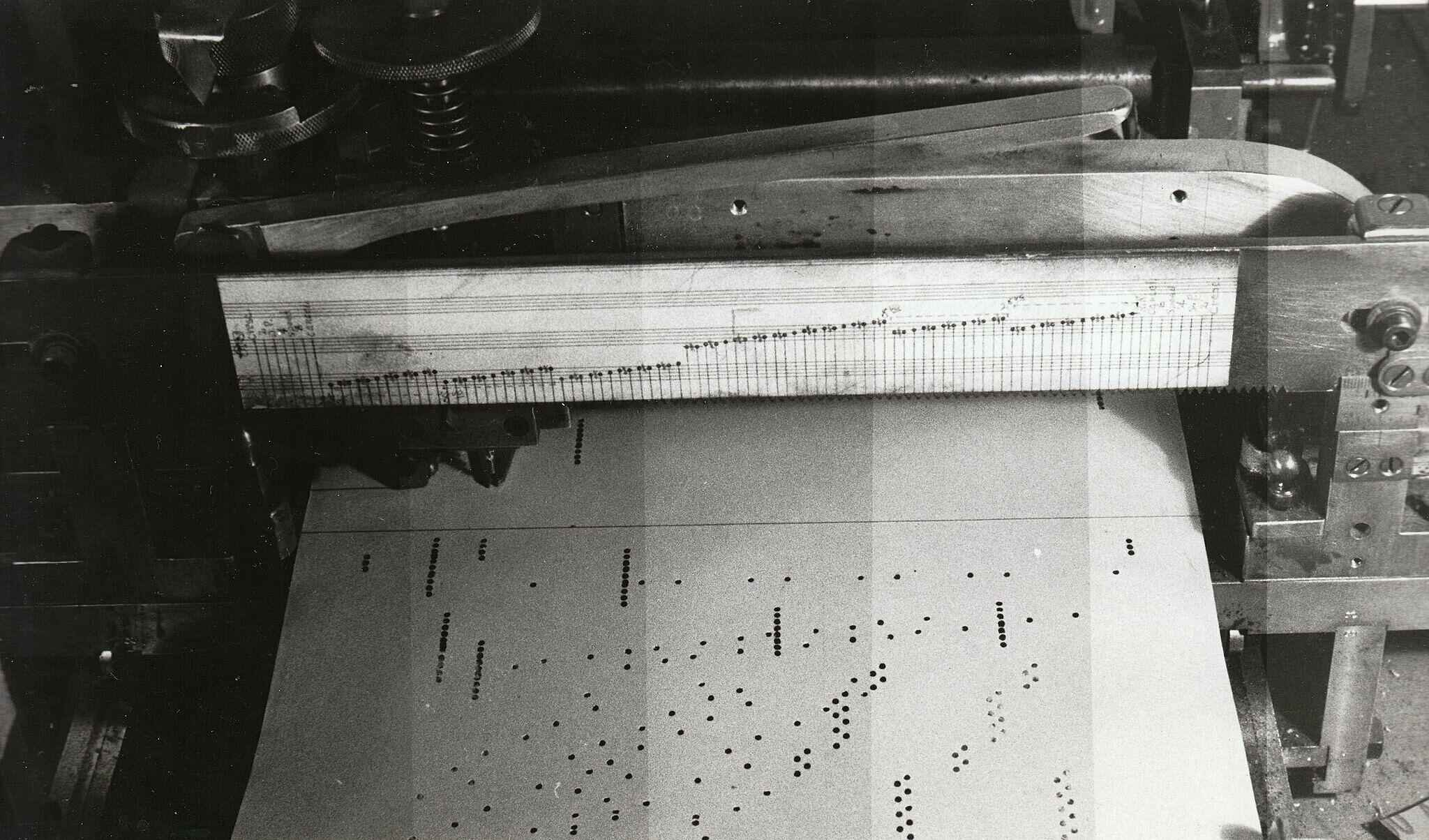

With their brittle materials—wood, rubber-coated fabric, and valves as fragile as eardrums—the few player pianos that have survived the last century are painstakingly difficult to restore. Preparing one to play a score by composer Conlon Nancarrow, whose whirlwind compositions are unmatched in speed and complexity, requires an unusual amount of mettle. While most pieces for player piano mimic a single performer, Nancarrow's Studies contain more notes in quick succession than three people sitting shoulder-to-shoulder could play at once. They are demanding to perform, even for a well-oiled machine.

Finding such a machine was one of the first challenges the Whitney faced in mounting the first United States retrospective of the composer’s work. Since their heyday in the 1920s player pianos have become increasingly rare, as have restorers capable of fixing them. After sourcing a 1921 Marshall and Wendell Ampico upright very similar to Nancarrow’s own and shipping it from Ohio to New York, the Whitney’s curatorial team reached out to restorers Terry Chamberlain and Mark Hennen of the Piano Technicians Guild to prepare the piano for what will be its most ambitious performance to date. On June 28, the last day of the festival, the Whitney will host a marathon, eight-hour concert featuring Nancarrow's fifty plus Studies.

Chamberlain attests that even routine adjustments frequently present surprises—and early on, it became clear that Nancarrow’s compositions called for a considerable overhaul. He described one of his first tests: after playing commercially-produced, stock rolls without issue, he loaded a Nancarrow roll. “We thought the piano was going to crash and burn. The whole thing was shaking.”

Nancarrow customized his machine so it could keep up with the barrage of perforations in his music rolls. Chamberlain and Hennen needed to match those changes. “We knew that Nancarrow modified his machine for speed, but the only thing we had to go on was an original recording of Study #36 from the 1970s,” said Chamberlain. “The recording was about four minutes and three seconds long, but when we first played it on this piano, it lasted five minutes and fourteen seconds.” When the restorers succeeded in bringing up the speed by more than twenty-five percent, they started to hear other problems. At that tempo, if one key released even a fraction of a second slower than another, the sound became muddy. Every key had to release at exactly the same rate.

To make the Whitney's renditions as accurate as possible, the restorers also needed to replicate changes Nancarrow made for sound quality. On an ordinary piano the high notes ring and overlap. Nancarrow added dampers to create clean tones, and also put in percussive brass tacks that produce, in Chamberlain's words, “a sharp, clacking, brilliant sound.” The standard tacks that Nancarrow likely used are no longer available, so Hennen designed a new set from scratch.

Though many of their adjustments were custom, some of the restorers' concerns were inherent to the instrument. The player piano is a vacuum-driven system, and maintaining high pressure is a common problem. If at any point the pressure is lost, so is the sound. While the abundant perforations in Nancarrow’s rolls invite air to seep out, here Chamberlain and Hennen encountered a bit of good luck. Nancarrow created his Studies in Mexico City, which is a mile high. “Fortunately,” said Chamberlain, “here in New York we’re at sea level. We'll get the highest volume and best percussive effects here—better than Nancarrow could have achieved at 7,000 feet."

Anywhere In Time: A Conlon Nancarrow Festival continues through tomorrow, June 28.