Interview: Flawless Sabrina, Zackary Drucker, and Elisabeth Sherman

Oct 23, 2015

In She Gone Rogue, a film by 2014 Biennial artists Zackary Drucker and Rhys Ernst, a character named "Darling" (played by Drucker) encounters figures central to the history of transgender women. Among them is Flawless Sabrina (Jack Doroshow), an icon of drag performance whose longtime apartment on East 73rd Street has similarly become legendary as a transformative space and a hub. As part of their Biennial contribution, Drucker and Ernst invited Flawless Sabrina to hold tarot card readings in the apartment, which is situated just a couple blocks from the Whitney’s Marcel Breuer building on the Upper East Side. Over the course of the exhibition, Flawless Sabrina hosted over 100 Biennial visitors there.

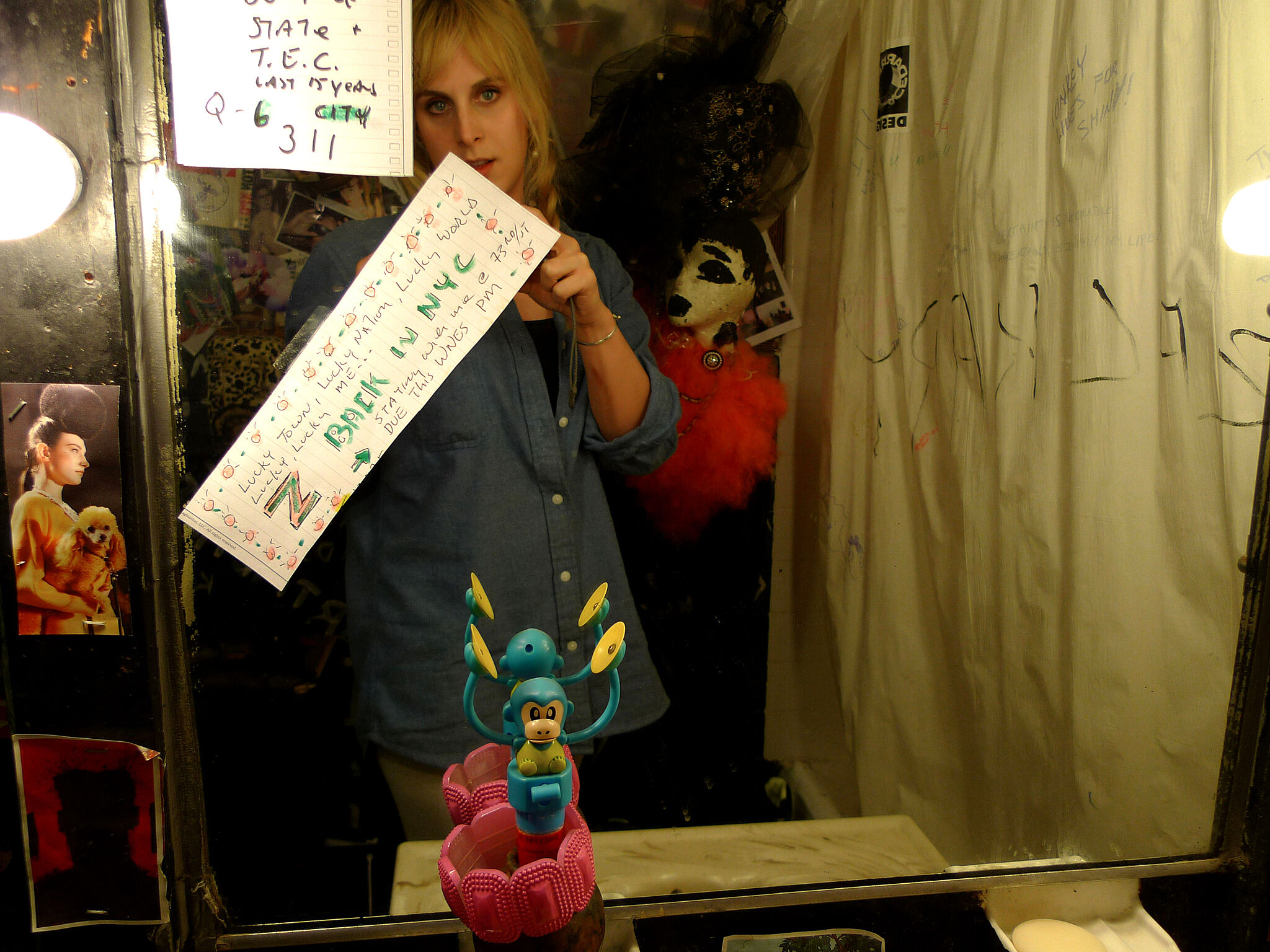

In this conversation, Flawless Sabrina, Zackary Drucker, and Elisabeth Sherman, Senior Curatorial Assistant at the Whitney, discuss the tarot card readings; the first drag contest Flawless Sabrina initiated in 1959; and the ever-changing landscape of New York City. The interview is illustrated by snapshots taken by Drucker inside the apartment.

Elisabeth Sherman: How did this idea [of the tarot card readings] come up?

Flawless Sabrina (a.k.a. Jack Doroshow): Well, I wouldn’t be doing this if it weren’t for my grandchild, Zackary Drucker. I learned tarot because my grandmother was a card reader. My dad died when I was six, and sometime between six and seven my grandmother said, “I need somebody to read my cards, so I’m going to show you how to do it.” As opposed to saying, “Do you want to learn?” She was so clever.

When push comes to shove, the cards are a device. It’s really about the communication between people, and the energy. The cards are the same way as your choices in clothing, or in language—a point of view. No more than you want sexuality to be brittle, neither with the cards. And if there’s going to be any flexibility, let it be toward positive energy. Let it be about encouragement. Let it be about something that will put wind in your sails.

ES: I’d like to hear about what the process has been like, and the kinds of people you’ve been meeting. Has there been a wide range?

FS: Not as broad a range as one might expect. I find [they’re] exemplary—very bright, aware, curious. Lots of workaholics. . . . It’s just been extremely informative. For myself I do cards, for my family and my friends, but except for charity things and rare occasions, I really haven’t had this sort of experience. I try to learn from everything.

ES: What are some of the memorable moments?

Zackary Drucker: A lot of crying, right?

FS: There has been, actually. But I think that’s been cleansing and useful, because that’s what [participants] say. I take their word for it. . . . Again, the cards may be some device, but I think in the main it’s really between the people. None of it has been negative. It has all, without exception, been very positive. And the kids themselves—it doesn’t take much to bring that positivity out.

. . .

ES: How do you two find your intergenerational relationship? It’s easy to say what wisdom brings to youth, but what has youth brought to wisdom?

FS: [Zackary’s] my mentor. . . . If she didn’t exist I’d have to invent her.

ES: And what about you, Zackary?

ZD: Flawless and I have known each other now for thirteen years. I was eighteen years old and I had just moved to New York. I met her at Wigstock and took a picture of her. She was totally done up and Victorian-garbed, with this big Marie Antoinette wig and huge dress, petticoat, the works. . . . And you said to me—

FS: I told you that you were on the wrong side of the camera—that’s what I said. And indeed you were.

ZD: And I hung that picture on my wall and continued to see [you] out in the clubs. I remember I saw you at Spa Club, which was on 13th street, between University and Broadway. . . . It’s now an expensive wine shop.

. . .

ES [to FS]: What brought you to this neighborhood?

FS: It was quiet, it was in the back of the building, and the fireplace worked. I come from Philadelphia, and I came to New York to make The Queen. It was again about the evaporation of a certain time in history.

. . .

ES: Do you think that [your understanding of and relationship to gender] would have been different, that you maybe would have identified differently, had you come of age now?

FS: Oh, of course, totally. . . . I got a lot of felonies from doing the contests. Believe it or not, cross-dressing is probably still on the books in a lot of places. It was basically a man in a conservative dress would find me guilty of a felony for being in a gaudy one. It’s a strange sort of dynamic [All laughing] . . . It took me a very long time in my life to get over being angry all the time. I mean, really angry. . . . It just made me furious. It not only seemed illogical; it was also so unkind. I didn’t go around pointing my finger at people, telling them how to live or what to do, or who to sleep with or how to dress. And I wasn’t teaching people to do that. I just was like a cork in the ocean, and by serendipity became involved in something, which in retrospect looks like pioneering, but I don’t think it was anything of the sort. It was just cultural change, and I happened to be in the right place at the right time—or the wrong place at the wrong time, depending on your point of view.

ZD: I was listening to a recording yesterday on the plane about the interconnectedness between people, and the way the collective unconscious works is that ultimately ideas are released simultaneously. You see that throughout time. Photography formed in different parts of the world at the same time: France, Britain, there’s even evidence that there were inventors in South America working on it . . . The telephone is the same way. Edison was just the first one make it to the patent office. Basically it was simultaneous.

ES: We’re all conduits for the history of the time we’re living in. But it also goes back to marketing. Whether or not you’re the first—you could be the fifth—you’re the one who hits on a way of communicating with the public that the general public can be receptive of.

FS: To me, technology and magic are indistinguishable, when it’s genuinely about an advancement. In the same ways it happens in technology, so [it happens] with society and social concepts. And hopefully we’re flexible. It’s not necessarily that we are always learning, because I think a lot of it is probably false starts, and a lot of it probably is parlor tricks.

ZD: Going back to 1959, the first year you ran a drag contest, what was happening in the collective consciousness at that point?

FS: The first drag contest I saw was in New York at the Manhattan Center. Some friends of mine from my school and I were at the Sloane House YMCA, and there were a couple guys getting in drag down the hall. One of my friends had never seen anything like that before, and I’m always curious. I still remember to this day, they called themselves Betty Grable and Estelle. They were from Pittsburgh. So I convince my friends. It was $5 a head to get in. We sat up in the balcony, always trying to figure out how to get rich. We looked at this thing, and the place was packed.

At the first contest we did in Philadelphia, the only out homosexual that we knew [performed], and [we had our] advance person start a phone tree because there was no advertising. . . . After the contest, [my friends’ parents] said, “lay down with pigs—smell like garbage.” My mother said, “How much did you make?” I said “$600.” She said, “You go girl.”

ZD: $600 in 1959—

FS: It was like $6,000, in one night. It was a fortune. Up to that point I was working in the hospital at school and as a car hop on roller skates, and between the two jobs I was lucky to make $60 a week. To make $600 in one night? That was beyond human comprehension. I was a slum kid! We emceed that first show, not in drag. The audience hated us. I had no idea where these people came from. I didn’t understand any of it.

ZD: Where did the contestants come from?

FS: No idea, [laughing], word of mouth. We put together a phone tree, and five or six queens made 10 calls a day. . . . Our most successful contest was in Atlanta, and a lot of the queens had come from Savannah. We went to this little sleepy town, and we [held a] runoff for three days to try to limit it down to smaller [groups]. And even then, I think the contest lasted for 20 hours. It was endless—coming out of the woodwork with hoop skirts and sausage curls and, “Darling, get me a cocktail!”

[All laughing]

FS: It was a learning experience. Very much like life itself.

ES: I was thinking as you were talking that as much as things change is how much they stay the same. Based on my limited knowledge of community building in L.A., it seems like it arises the same way. People find like-minded people, and it’s word-of-mouth, and eventually attention is paid from the outside.

ZD: I totally agree. And I think in Los Angeles that still happens in an organic way.

ES [to FS]: You’re so New York, a part of the history of this place. How is New York today in comparison to L.A.?

FS: Until this show at the Whitney, I thought this place was as dead as Kelsey’s nuts. I was jealous of Los Angeles for supporting its artists and actually reflecting contemporary creativity. Gender-centric is my point of view, so that aspect was certainly pertinent, but . . . artists have to have space. And to have [The Whitney], this exquisite space, right across the street . . . to afford the space for this brilliance—yes please.

The Whitney’s always been sort of a marker for me; when I first moved to New York in 1967, I saw Yoko Ono jump into a big thing of mud and get it all over the investors. And I took my mom to the Bill Viola show just before she died. And now I’ve lived long enough to see my baby there—

But I think that this neighborhood has become so brittle. The spontaneity evaporated. That’s why the moving of the Whitney is so important. I think the Whitney is going where the town is young again. The Whitney should move into the future. That’s where it belongs. That’s what it’s about.

. . .

ES: I’ve been thinking a lot about politics and art, the idea of a spoon full of sugar. When do we want to soften the blow, and when is it appropriate or beneficial for art to be as aggressive and difficult as the issues it’s grappling with?

FS: Art is politics, isn’t it? It’s the only currency. The framers [of the Constitution] required [provocation]. In order to have a democracy, you have to question. Art provokes questioning. Art should be about putting a stick into a hornet’s nest. But I like getting jam, and you know I like giving jam, so I don’t find it appealing to aggravate people. If I’m doing the best I can, I have to give the other person license that maybe they’re doing the best that they can, as well. People have completely opposing points of view, and listening to them, I learn a lot where I had previously closed off. Because I had totally disagreed with the premise, I didn’t really hear them out. You have to allow for that sway, and the less brittle the better. For our system of government to work, there has to be that sway there. Otherwise we’re doomed. We have to question: maybe it’s this way; maybe it’s that way; probably it’s a bit of both. There’s some good in all bad. There’s some bad in all good.