Preserving Privacy: On the State of Surveillance

Apr 29, 2016

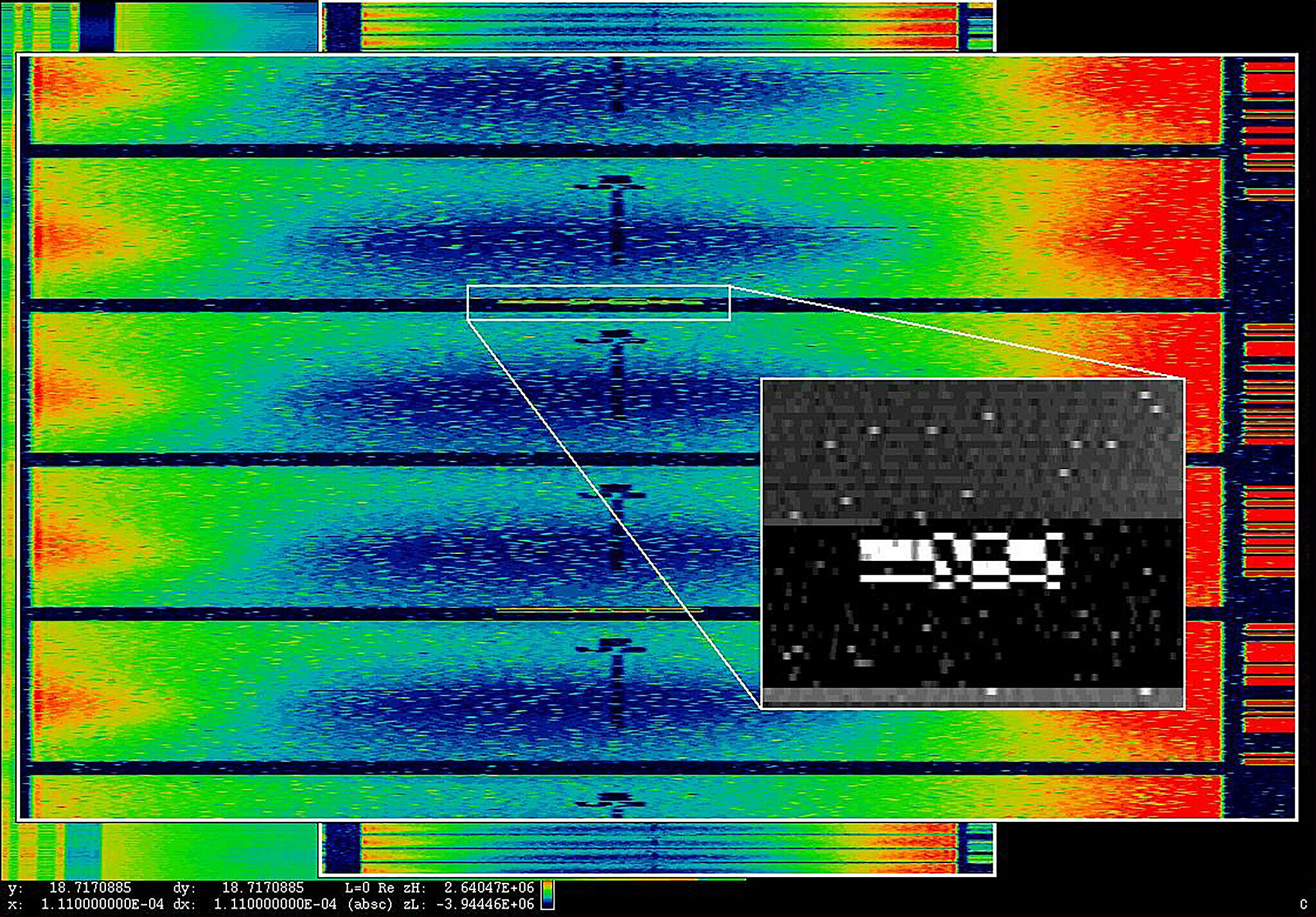

As part of the exhibition Laura Poitras: Astro Noise (February 5–May 1, 2016), the Whitney co-hosted a three-day series of events with the Freedom of the Press Foundation, expanding on ideas Laura Poitras explores in her work. Journalists and activists held a Cryptoparty, guided discussions on the Freedom of Information Act, and led tutorials on encryption tools such as TAILS, a privacy-preserving operating system.

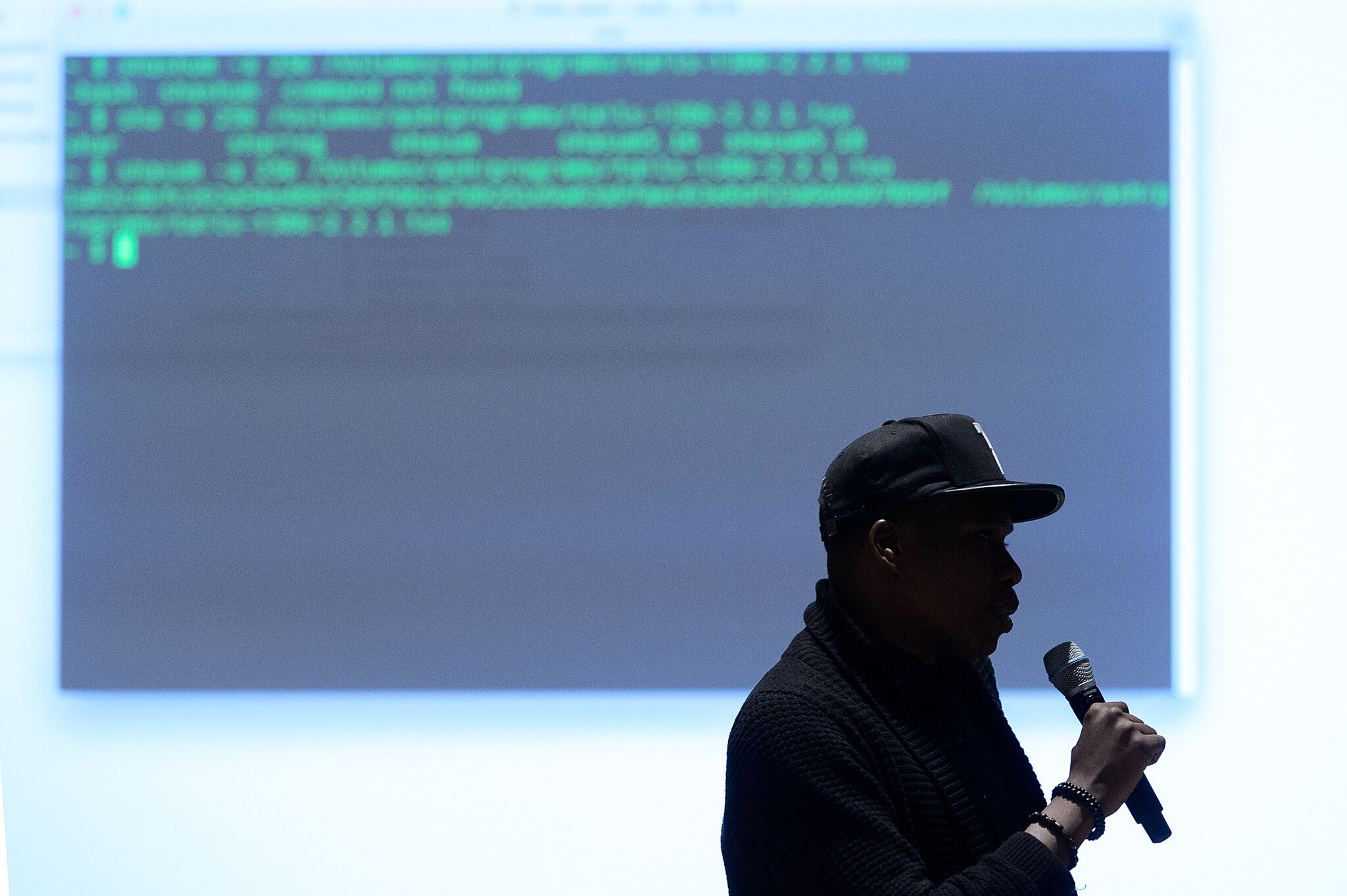

In the midst of this activity, participants and workshop leaders Allison Burtch, Harlo Holmes, David Huerta, and Mathew Mitchell paused to describe the role of surveillance in their own lives, and to offer thoughts on the work that still needs to be done around privacy today.

Matthew Mitchell

Surveillance affects me and my community from the minute I wake up to the minute I go to sleep. I live in Harlem, and unlike everyone who uses surveillance as a theoretical device, it’s very real when you walk outside and almost every street corner has an NYPD surveillance camera, and every bodega has three or four small, cheap surveillance devices. There are SkyWatch towers, police boxes on legs that look like scary voltron robots, looking out onto the community. [The police] have mobile command centers on 125th and Lexington, permanently parked outside the grocery store with monitoring equipment and large antennas.

Harlem has one of the first and largest public WiFi networks in the city, but when you access it, you’re accessing a database that’s run by the state and the city. All your information is on there, available to hackers and also law enforcement. You throw in truancy police, and it’s a really strange environment. It’s like a lab for surveillance that will be common five or ten years from now in other communities.

The work to be done is education and advocacy. I have open office hours in my community, a three-hour window every month. I invite specialists, whether they’re security activists, researchers, hackers, or amazing developers, to talk to the community about what they can do to protect themselves: to be safe online with these new tools and technology.

Harlo Holmes

I’ve always been an "I don’t have anything to hide” person, and I still kind of feel that way. But even if I don’t have anything to hide, it should always be my choice: I should have the tools to decide who gets access to my information and data, when and why, and under what circumstances.

There are plenty of initiatives that use patron or user data to gain insights about an organization or city. Those initiatives are great when people opt into them; however, the question is about data retention: How long has that data been hanging around on servers? How is that data going to be framed, and what recourse do users or patrons have when that data falls into the wrong hands?

The Freedom of the Press Foundation has done a lot in terms of advocacy, on encrypted websites, for example, or websites that use https, over the past couple of years. Making sure people know to look at sites with the green [padlock] in the corner of their favorite web browser was a huge campaign that took a lot of work and coordination. Now we’re focusing on the other side of the coin; we have to make sure that services and websites that people use—like whitney.org or newspapers—provide encrypted services.

Allison Burtch

It’s cool that we should have these tools, but what are you trying to protect yourself from? Is it corporate surveillance? Political surveillance? Is it from your mom surveilling you? There are so many different types of surveillance, and broad strokes are difficult to talk about. [It becomes] a general, nebulous concept.

When you look at tools such as TAILS, or Tor [another fully-encrypted software program] that was created by the United States Navy, without looking at the political motivations of specific entities, then it can get really unclear. The U.S. government can operate through Tor, and at the same time activists can protect themselves with it.

What’s great about what Laura [Poitras] has done is that [surveillance] is not a nebulous concept. She did some very specific political things that offended this capitalist, hegemonic, imperialist state power.

David Huerta

I consider surveillance in terms of what it might look like in my lifetime. Somebody might believe they have nothing to hide in 2016, but a lot can change within the span of the rest of your life. And like diamonds, data doesn't die. It's forever.

It's something to consider as you're creating dossiers of yourself around different cloud services, social media, etc. Even though right now you might have nothing to hide, your future self might wish you could hit the undo button.

“Easy to use” and “cryptography” don't always go hand-in-hand. These tools are not made to be the biggest, next, new thing. They’re usually made by volunteers, and [supported] by weird sources of funding. We have developers volunteering their time, but we don't have all of the other people who are desperately needed to make good software. You need developers, but where are the designers? Where are the usability experts? Where are the quality assurance testers? Where's the marketing team? Things don't accidentally become popular. If you want to proliferate these tools, you have to do all of the things that other companies are doing.