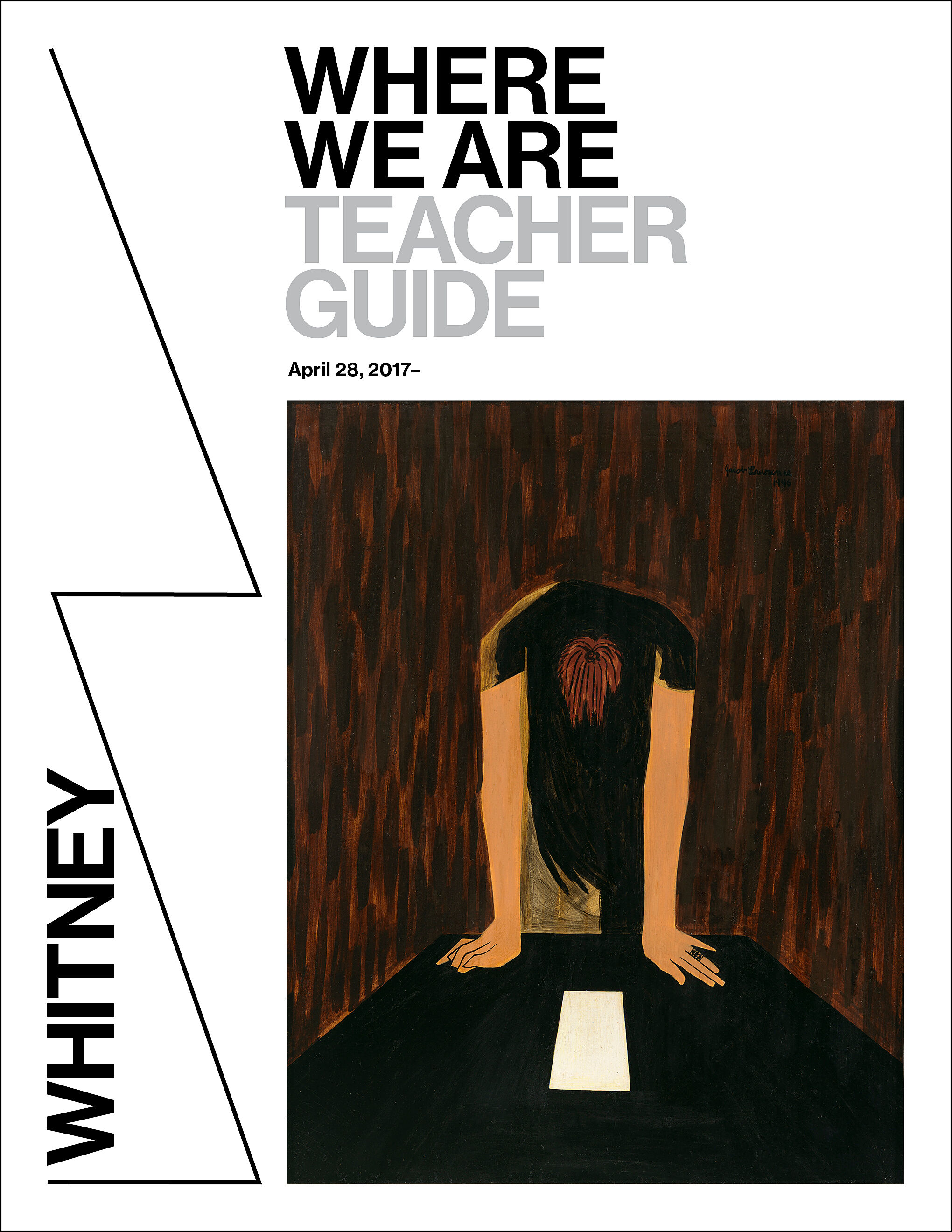

Teacher Guide:

Where We Are: Selections from the Whitney's Collection 1900–1960

May 26, 2017

Welcome to the Whitney!

Dear Teachers,

We are delighted to welcome you to the exhibition, Where We Are, on view at the Museum through Spring 2018. The exhibition presents selections from the Museum’s collection. Focusing on works made from 1900 to 1960, Where We Are traces how artists have approached the relationships, institutions, and activities that shape our lives.

This teacher guide provides a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offer suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts.

We look forward to welcoming you and your students at the Museum.

Enjoy your visit!

The School and Educator Programs team

Where We Are: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1900–1960

Focusing on works made from 1900 to 1960, Where We Are traces how artists have approached the relationships, institutions, and activities that shape our lives. Drawn entirely from the Whitney’s holdings, the exhibition is organized around five themes: family and community, work, home, the spiritual, and the nation. During the six decades covered in the exhibition, the United States participated in two world wars, experienced economic collapse, and faced social discord. Where We Are, as well as each of its sections, is titled after a phrase in W. H. Auden’s poem “September 1, 1939.” Auden, who was raised in England, wrote the poem in New York shortly after his immigration to the United States and at the very outset of World War II. The title of the poem marks the date Germany invaded Poland. While its subject is the beginning of the war, Auden’s true theme is how the shadow of a global emergency reaches into the far corners of everyday life. The poem’s tone remains mournful but concludes by pointing to the individual’s capacity to “show an affirming flame.” Where We Are shares Auden’s guarded optimism, gathering a constellation of artists whose light might lead us forward.

More information about the exhibition

W.H. Auden, "September 1, 1939"

September 1, 1939. Poem from Another Time by W. H. Auden, published by Random House. Copyright © 1940 W. H. Auden, renewed by the Estate of W. H. Auden.

Pre-visit Activities

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the exhibition. We have included some selected images from the exhibition, along with relevant information that you may want to use before or after your Museum visit. You can print out the images or project them in your classroom.

Pre-visit Objectives:

- Introduce students to the artists and works in the exhibition.

- Examine themes students may encounter on their museum visit.

- Explore how artists interpreted American life in the early to mid-twentieth century.

CHARLES HENRY ALSTONTHE FAMILY, 1955

Charles Henry Alston created this family portrait in bold blocks of color and lines that he carved into the paint with a palette knife—a tool with a blunt steel blade that artists often use for mixing or applying paint. Alston wrote that this painting was ". . . an attempt to express the security, stability, and human fulfillment which the ideal family represents. Artistically my problem was to find the painterly equivalents for these qualities, as well as tell the story. Such a theme calls for a compact, well organized design with subtle harmonies and discords and a certain solid, monumental quality."

LOUISE BOURGEOISQUARANTANIA, 1941

After emigrating from Paris to New York in 1938, Louise Bourgeois soon embarked on a series of carved and painted wood sculptures, which she called “Personages,” that evoked the upright human form. The sculptures, she explained, were a way of recreating all the people she had left behind in her homeland. Quarantania, an early example from this series, consists of five elongated forms huddled on a pedestal, in a “duel,” as she put it, “between the isolated individual and the shared awareness of the group.” She alluded in part to her own childhood; Bourgeois came from a family of five and the group in Quarantania not only resembles human figures, but also sewing needles or weaving shuttles, the tools of her family’s tapestry restoration trade.

Artist as ObserverNO ONE EXISTS ALONE

American artists have often depicted their families and communities. Louise Bourgeois explored the relationship of the individual to the group and of the child to the family. The family was also a recurring theme in Charles Henry Alston’s paintings. Bourgeois carved the abstracted forms of Quarantania, 1941 out of wood. In The Family, 1955, Alston used a palette knife to carve into the paint.

a. View and discuss these works with your students. What do students notice? Have students describe the relationship between the subjects in each of the works. Consider the figures’ facial expressions in Alston’s painting as well as the body language and grouping of the figures in both works. How does each artist show connections between the figures? Do these families seem happy? Sad? Ask students if they’ve ever posed for or drawn a family portrait. What expression did they have on their faces?

b. Charles Alston made decisions about the furniture, background, and objects in his portrait, while Bourgeois used an object to represent her family. If your students made an artwork of their family, what would they include? Pets? Objects? What would they put in the background? If your students picked an object to represent each member of their family, what would they choose, and why?

c. For older students: Alston remarked that the theme of the family “. . .calls for a compact, well organized design with subtle harmonies and discords and a certain solid, monumental quality." Ask students to brainstorm how these characteristics might also apply to Bourgeois’s sculpture.

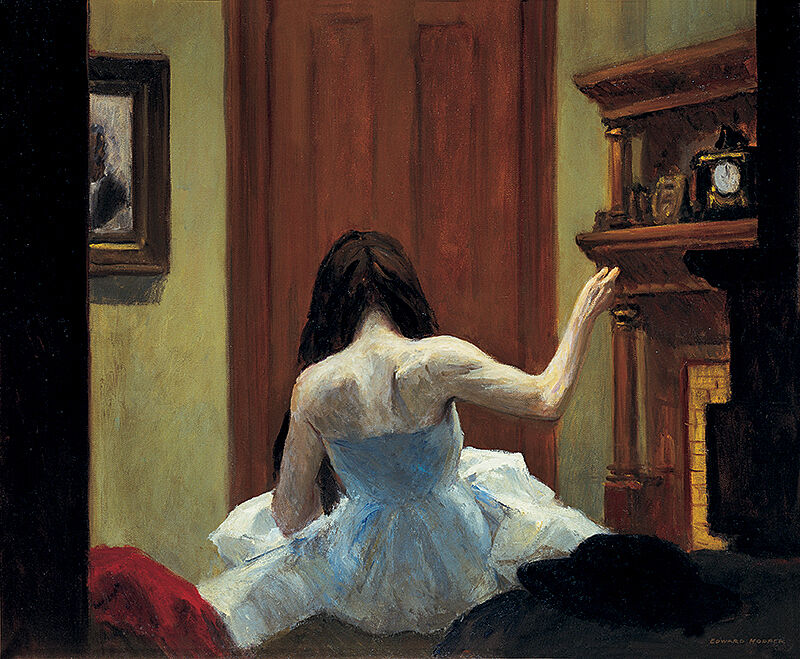

Edward HopperNEW YORK INTERIOR, C. 1921

An early example of Hopper’s focus on private, indoor scenes, New York Interior offers an unconventional view of a woman sewing. The scene depicts the impersonal, yet strangely intimate quality of modern urban life. We glimpse this private moment as voyeurs through a window, with the figure’s turned face and exposed back heightening her anonymity and our awareness of her vulnerability.

ARTIST AS STORYTELLERTHE FURNITURE OF HOME

The home and the domestic interior are familiar sources of inspiration for artists. Works that depict ordinary objects suggest that each of us sees our home uniquely. Even though our possessions might have something in common, our experiences of them are diverse and unique.

a. Edward Hopper shaped his view of the city by painting people as they appeared to him in brightly lit windows seen from passing El (elevated) trains—a view offered to millions of passengers on New York’s public transportation system. The back of the young woman in New York Interior is derived from this experience. Without telling them the date of this work, ask your students to describe what is going on in the painting. What do they think the woman is doing? By observing the painting closely, what can your students infer about the time in which it was made? What if the woman in Hopper’s painting was to turn around—what would happen next?

b. This painting could be considered as a snapshot of a moment in daily life, but it is only one moment in the story. What do students think happened before and after this scene? Use the image for a writing activity or ask students to use the template to expand the story before and after the moments that the artists chose to depict in the painting.

c. Have students imagine the scene beyond the edges of the canvas in two or more directions. What would they see? Students could have a discussion or do a drawing or writing activity based on this prompt.

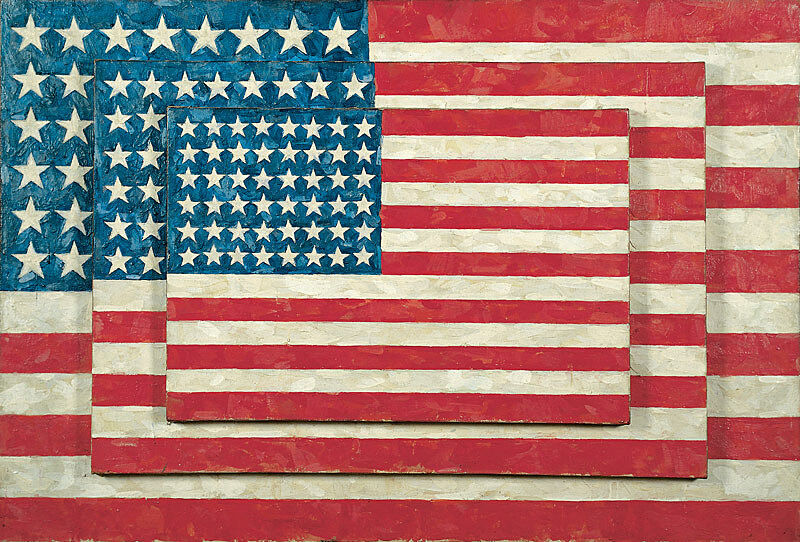

JASPER JOHNSTHREE FLAGS, 1958

In 1954, Jasper Johns began painting what would become one of his signature emblems: the American flag. As an iconic image—comparable to the targets, maps, and letters that he also has depicted--Johns realized that the flag was “seen and not looked at, not examined.” Three Flags draws attention to the process of its making through Johns’s use of encaustic, a mixture of pigment suspended in warm wax that congeals as each stroke is applied; the resulting accumulation of discrete marks creates a sensuous, almost sculptural surface.

Artist as ExperimenterIN A EUPHORIC DREAM

George Washington, the first president of the United States, famously described the nation as a "grand experiment." It also could be described as a collective dream. In addition to the lands and peoples that the United States encompasses, it remains a gathering of diverse—and competing—aspirations, beliefs, symbols, and histories. Artists have looked to these symbols and histories to study the nation's history and their contemporary moment.

Jasper Johns’s Three Flags (1958) presents the flag as a flat, stacked object in a way that we don’t usually see it. The painting is made with encaustic, a wax and pigment paint medium that dries immediately and freezes the flag in place. By positioning the flag in an unexpected context and in an unpredictable way, Johns questions the meaning of the flag and what it represents.

a. Discuss the American flag and Johns’s painting with your students.

- Where do students usually see flags?

- When they notice an American flag, what do they think of?

- What does the American flag represent to them?

- Is the meaning of the flag fixed or fluid? In what ways?

- How is Johns’s painting different from the flags that they might see in their classroom or school?

b. For older students: discuss: what Johns might mean when he realized that the flag was “seen and not looked at, not examined.” What is the difference between seeing and examining? What is the advantage of working with a subject that “the mind already knows?”

c. Have older students discuss whether making this work might be an act of patriotism. Conversely, how might it imply a critique of the United States? What do your students imagine viewers might have thought about in 1958 when they first saw this painting? What do your students think of when they look at this painting today?

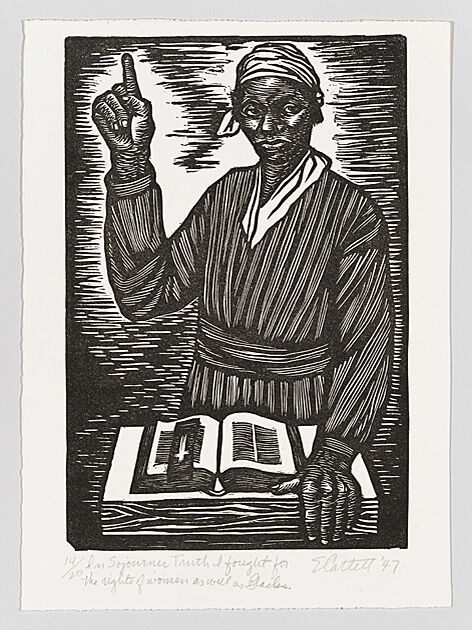

ELIZABETH CATLETTPRINTS

This work is from a series of fifteen linoleum cut prints that Elizabeth Catlett made in 1947 at a workshop in Mexico City. They feature some famous African American figures including Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, and Phyllis Wheatley, but also unknown women at work, whether in the home, field, or factory. For Catlett, the idea was not only to celebrate exemplary figures like Sojourner Truth, but also the everyday labor of ordinary women.

ARTIST AS CRITICWOMEN AND WORK

This is an example of a famous woman that Elizabeth Catlett included in a series of prints about women and work. Sojourner Truth was an African American abolitionist and women's rights activist . She was born into slavery in Ulster County, New York, and escaped to freedom in 1826. In 1851 she delivered a speech at the Ohio Women's Rights Convention that was later known as Ain't I a Woman.

View and discuss Catlett’s print, In Sojourner Truth I fought for the rights of women as well as Blacks. Have students use the resources below to research Sojourner Truth. Then ask them to describe what they see in Catlett’s print. Consider her pose, the expression on her face, what she is wearing, and the objects in the image. Why do students think the artist chose to enlarge her hands? Discuss the title of this work. Why do students think that Catlett titled it in the first person?

Sojourner Truth - National Women's History Museum

Sojourner Truth - BlackPast.org

a. If your students made a series of both famous and unknown women, who would they include? As a class, think of at least five women they think of as heroines. Include women who are contemporary or historical, famous or unknown.

View and discuss thumbnail images and titles of Catlett’s series of prints here

If student groups made a portrait of the woman they researched, what title would they give it? Why?

Post-visit Activities

Post-visit Objectives

- Enable students to reflect upon and discuss some of the ideas and themes from the exhibition.

- Have students further explore some of the artists’ ideas through discussion, art-making, and writing activities.

Museum Visit Reflection

After your museum visit, ask your students to take a few minutes to write about their experience. What new ideas did the exhibition give them? What other questions do they have? Ask students to share their thoughts with the class.

ELSIE DRIGGSPITTSBURGH, 1927

Elsie Driggs was inspired to make this painting by a childhood memory of Pittsburgh’s steel mills. Returning twenty years later to capture the scene, she initially tried to paint it from inside the mills. But the owners thought the factory floor was no place for a woman, and management worried that she might be a labor agitator or industrial spy. As much as the painting may seem to viewers today to be a warning about the dangers of industrial pollution, Driggs had no critical agenda. She ended up basing the work on drawings she made from a hill above her boardinghouse, later writing that she stared at the mills and told herself: “‘This shouldn’t be beautiful. But it is.’ And it was all I had, so I drew it.”

JOSEPH STELLATHE BROOKLYN BRIDGE: VARIATION ON AN OLD THEME, 1939

Joseph Stella captured the dizzying height and awesome scale of the Brooklyn Bridge from a series of fractured perspectives, combining dramatic views of radiating cables, stone masonry, cityscapes, and night sky. The large scale of the work—it is nearly six feet tall—conjures a Renaissance altar, while the Gothic style of the massive pointed arches evokes medieval churches. By combining contemporary architecture and historical allusions, Stella transformed the Brooklyn Bridge into a twentieth-century icon of modern life and the Machine Age.

Artist as ObserverTHE STRENGTH OF COLLECTIVE MAN

During the first half of the twentieth century, the United States experienced the deepest economic downturn in the history of the industrialized world, and recovered as the nation became embroiled in World War II. American artists responded to this seismic moment in the history of labor with works that portray the sites of production, scenes of working, and the individuals who constitute the work force. By making labor a central theme of artistic production, American artists also were asserting themselves as fellow workers at a moment of collective efforts. Art, of course, is work.

a. Artists Elsie Driggs and Joseph Stella were (respectively) inspired by steel mills in Pittsburgh and the Brooklyn Bridge—both architectural structures that were built for specific purposes and had particular effects on their surroundings. Ask your students to review and discuss these paintings. How do the artists represent these structures? Why do students think the artists chose to paint these structures? Which parts were they most drawn to? What shapes, lines, and colors did they use to represent these parts?

b. Ask your students to take photographs or make drawings of a building or architectural structure that they admire in their city, town, or neighborhood. For example, a public building, a skyscraper, a bridge, a factory, or a house. If possible, have students research their selected site, including its history and original purpose.

c. Ask students to present and discuss their photographs, drawings, and findings. What did students choose to depict? Why? What did they discover about their selected sites? What are these buildings or structures used for today? What effect do they have on their surroundings? On people?

HERMAN TRUNK JR.MOUNT VERNON, 1932

Herman Trunk Jr. worked in his family’s printmaking business in Brooklyn by day and painted at night. He exhibited with artists such as Charles Demuth, Joseph Stella, and Stuart Davis in the 1930s and 40s. A 1939 exhibition review in The New York Sun describes Trunk’s approach: “He will paint in the same composition the outside of a house and its interior as well, present within a single frame, three seasons at once, and yet in either case contrive to weld the whole into a decorative entity. It is much like the fragmentary, unrelated, yet overlapping, glimpses that come in dreams, or the way logically disconnected, though vividly realized bits of experience, flash on the drowsing memory when it is not focused intently on any particular thing.”* In Trunk’s depiction of George Washington’s family home, the building is pulled apart to reveal another Mount Vernon. A surreal painting of a real place, it affirms that the dream and the reality of the nation are inseparable.

*Catalogue, Grant Studios: Herman Trunk Exhibit, 11–27 March 1939. Smithsonian Archives of American Art

Artist as ExperimenterINSIDE AND OUT

Mount Vernon was the plantation house of George Washington, the first President of the United States, and his wife, Martha Dandridge Custis Washington. One of the most iconic historic homes in the United States, it is situated on the banks of the Potomac River in Fairfax County, Virginia. The mansion is built of wood in a loose Palladian style, and was constructed by Washington between 1758 and 1778.

a. Ask your students to use the resources from the Mount Vernon website below to compare Herman Trunk’s painting with images of the actual house, inside and out. Explore and discuss what Trunk has changed from the original image.

George Washington's Mount Vernon Virtual Tour

Mount Vernon room-by-room tour

b. Older students could use the resources below to look at examples of Palladian architecture and its conventions, such as proportion, symmetry, temple facades, and the use of classical orders in general to determine which architectural features Trunk chose to include in the painting and what he left out.

Palladian architecture - Wikipedia

Palladio: The architect who inspired our love of columns - BBC.com

c. Ask students to take and print photographs of their school, inside and out. Have each student make a collage that combines both views. View and discuss their collages. Did students reveal something new or about their school by rearranging its parts?

d. For older students: have students use the resources below to research Mount Vernon and its history of slavery. Taking into account this complicated history, do students have any new thoughts or questions about Trunk’s painting?

Slavery at Mount Vernon:

MountVernon.org - Lives Bound Together

The Private Lives of George Washington's Slaves - PBS.org

Slavery and the Making of America - Thirteen.org

Additional lessons on slavery:

For high school students:

Knowledge is Power - Thirteen.org

For junior high school students:

What We Leave Behind - Thirteen.org

For elementary school students:

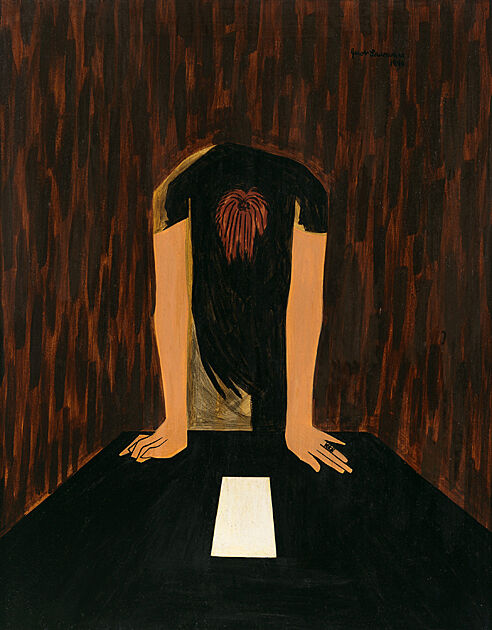

JACOB LAWRENCEWAR SERIES, 1946-1947

In 1946, a year after the end of World War II, Jacob Lawrence began work on the fourteen paintings that comprise the War Series. The images are based on the artist’s own experiences of serving with the Coast Guard, and present a narrative, like chapters in a book. Lawrence said that he wanted these works “to capture the essence of war” by “portraying the feeling and emotions that are felt by the individual, both fighter and civilian.” Historically, paintings of war have most often emphasized the triumph of victory. In these images, however, heroism cannot be separated from drudgery and suffering, nor is victory free from sorrow and loss.

ARTIST AS STORYTELLERUNEXPECTED VIEWPOINTS

a. Review and discuss The Letter with your students. Observe the body language of the person in the painting and the colors Lawrence chose to use for this work. What can students infer by looking closely at the painting? What could be in the letter?

b. Paintings of war usually celebrate victory or tragedy on a grand scale, but Lawrence’s War Series (1946-1947) reminds us that the nation has been built on both tragic and heroic acts. How is the War Series different in this respect? Have students discuss the moments in the story that Lawrence chose to represent.

c. Ask students to use the war photography resources below or think about images that they’ve seen in the media to discuss how war is portrayed today. Compare the contemporary images with images of World War II photography and Lawrence’s paintings. What do students notice?

Brief PBS Essay on Photography and War

d. The Letter is one of a series of images that represent war. As a class, collectively think of one issue that is important to your students. Ask each student to represent the issue in one drawing or painting in an unexpected way, such as a quiet, active, or an anticipatory moment. What did they choose to represent? Why? Have students arrange their works into a series. What is the story that is told by looking at the works as a series?

Georgia O’KeeffeMUSIC PINK AND BLUE No. 2, 1918

In her abstract paintings, Georgia O’Keeffe invented a new and original language of form and color. Rather than depicting the outward, tangible forms of nature, she evoked the experience of being in nature, enveloped by an infinity and wonder that could not be expressed in words. Using a vocabulary of undulating, biomorphic forms and a technique of gently feathering her palette of hues into one another, she created animate, breathing works that suggest the fluid rhythms of the natural world and portray emotions beyond conscious grasp.

Artist as ExperimenterOF EROS AND DUST

Searching for alternatives to what many saw as a culture of materialism and war, some American artists sought recourse in spirituality and mysticism. Rather than making particular declarations of faith, artists embraced the spiritual through the symbolic, the sublime, the natural, and the abstract. For these artists, art and the world were still domains of mystery, awe, and wonder.

a. Abstraction played a fundamental role in O’Keeffe’s art. It gave her a way to express feelings that she could not express in words. Many of O’Keeffe’s abstractions focus on her experience of people and places, rather than on realistic appearances. Some abstract work—like this painting—take the natural world and distill it to its most basic elements. Review and discuss Georgia O’Keeffe’s Music Pink and Blue, No. 2. Ask your students what they notice about this painting. Have students choose an area of the painting—a color or a shape that their eye is drawn to—and imagine what sounds it might make.

b. Ask your students to choose a selection of music without lyrics. Have them focus on line, shape, and shading to make musical sketches inspired by the sounds they hear. Have students notice how one sound flows into another.

c. Ask students to share and discuss their artwork with the class. How did they choose to represent the different sounds that they heard?

Bibliography and links

Miller, Dana, Ed. Whitney Museum of American Art: Handbook of the Collection. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2015.

Where We Are exhibition.

https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poem/september-1-1939

September 1, 1939. Poem from Another Time by W. H. Auden, published by Random House. Copyright © 1940 W. H. Auden, renewed by the Estate of W. H. Auden.

The Whitney’s collection.

The Whitney’s programs for teachers, teens, children, and families.

The Whitney’s online resources for K-12 teachers.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Mark Joshua Epstein, Whitney Educator;Dina Helal, Manager of Education Resources; Lisa Libicki, Whitney Educator; Heather Maxson, Director of School, Youth, and Family Programs; and Jamie Rosenfeld, Coordinator of School and Educator Programs.

Education programs in the Laurie M. Tisch Education Center are supported by the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation, the Dalio Foundation, The Pierre & Tana Matisse Foundation, Jack and Susan Rudin in honor of Beth Rudin DeWoody, Stavros Niarchos Foundation, Barker Welfare Foundation, public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, by members of the Whitney’s Education Committee, and contributions from family and friends made in memory of Jill Buttenwieser Schloss.

Endowment support is provided by the William Randolph Hearst Foundation, the Annenberg Foundation, Krystyna O. Doerfler, Lise and Michael Evans, Burton P. and Judith B. Resnick, Laurie M. Tisch, and Steven Tisch.

Free Guided Student Visits for New York City Public and Charter Schools are endowed by The Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.

src="https://whitneymedia.org/assets/image/819314/NYCulture.png">

Where We Are: Selections from the Whitney’s Collection, 1900–1960 is sponsored by