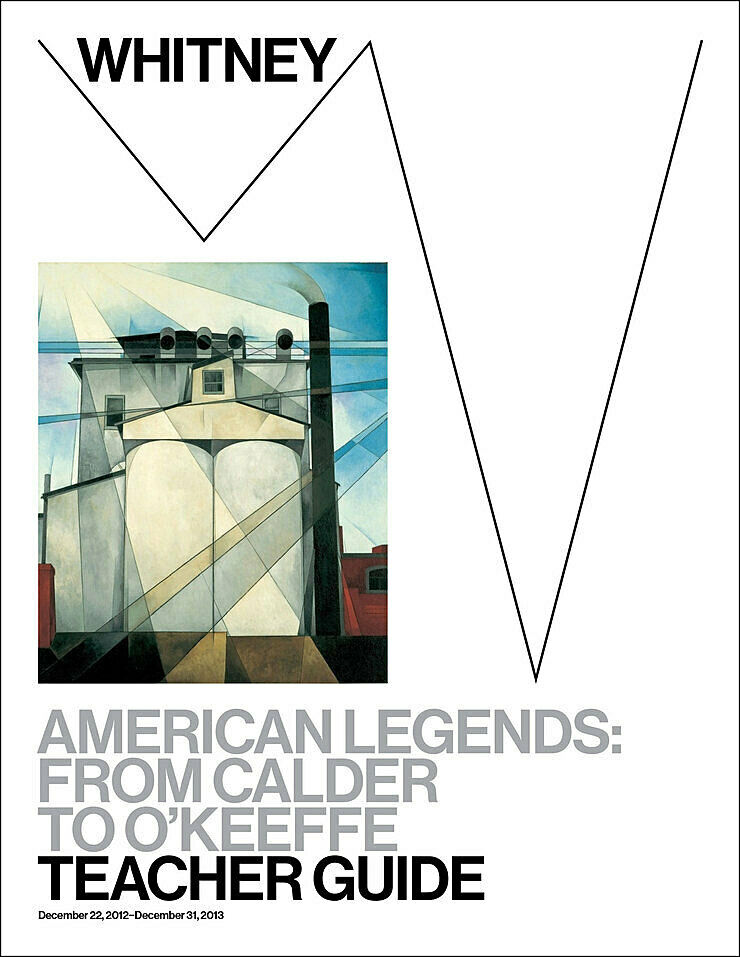

Teacher Guide:

American Legends: From Calder to O’Keeffe

Dec 22, 2012

About This Guide

1. How can these materials be used?

These materials provide a framework for preparing you and your students for a visit to the exhibition and offer suggestions for follow up classroom reflection and lessons. The discussions and activities introduce some of the exhibition’s key themes and concepts.

2. Which grade levels are these materials intended for?

These lessons and activities have been written for Elementary, Middle, or High School students. We encourage you to adapt and build upon them in order to meet your teaching objectives and students’ needs.

3. Learning standards

The projects and activities in these curriculum materials address national and state learning standards for the arts, English language arts, social studies, and technology.

4. Feedback

Please let us know what you think of these materials. How did you use them? What worked or didn’t work? Email us at schoolprograms@whitney.org.

About the exhibition

Eighteen American artists who forged distinctly modern styles in the early to mid-twentieth-century are the subjects of American Legends: From calder to O’Keeffe. Drawing from the Whitney’s permanent collection, the year-long show features iconic as well as lesser known works by Oscar Bluemner, Charles Burchfield, Paul Cadmus, Alexander calder, Joseph Cornell, Ralston Crawford, Stuart Davis, Charles Demuth, Arthur Dove, Marsden Hartley, Edward Hopper, Gaston Lachaise, Jacob Lawrence, John Marin, Reginald Marsh, Elie Nadelman, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Joseph Stella.

The Whitney Museum of American Art’s collection of early to mid-twentieth-century art offers a window onto the past, telling the story of how artists in the United States succeeded in creating a dramatic new visual language grounded in their diverse experiences as Americans. American Legends showcases the Museum’s extensive holdings of the work of eighteen iconic figures whose art helped codify the country’s sense of itself and its vision for its future.

Before 1900, American artists had taken their stylistic cues primarily from Europe; to them, America was a provincial backwater, devoid of culture. With the country’s growing prominence on the international stage came a newfound aesthetic confidence. Artists began to disentangle themselves from the influence of Europe by forging an art inherently related to the American experience. Two groups vied for dominance in the first part of the twentieth century: realists and modernists. The realists portrayed the people and everyday scenes of contemporary urban life with a robust impulsiveness that captured the vigor and optimism of a vibrant pluralist democracy. The modernists favored abstract transcriptions of their intuitive, emotional responses to both the natural and man-made world that surrounded them. Despite their seemingly antithetical styles, the two groups shared a determination to portray their intense connection to what were often distinctly American subjects. Together, they charted a new direction in American art and, in the process, redefined the relationship between art and modern life.

During the presentation of this exhibition, each gallery will be periodically reconfigured with new selections of work by the featured artist or by installations of the work of a completely different artist.

Before visiting the Whitney, we recommend that you and your students explore and discuss some of the ideas and themes in the American Legends: From calder to O’Keeffe exhibition. You may want to introduce students to at least one work of art that they will see at the Museum. See the Images and Related Information section of this guide for examples of artists and works that may have particular relevance to the classroom.

Objectives:

Introduce students to the works of prominent American artists and how they represented early twentieth-century modern life.

Introduce students to the themes they may encounter on their museum visit such as “Artist as Observer” and “Artist as Experimenter.”

Make connections to artists’ sources of inspiration such as the New York City, nature, and the modern world.

During the early part of the twentieth century, American artists looked for new ways to depict the world around them and define an American art, distinct from its European counterparts. Some artists focused on the dynamism and novelty of the modern metropolis and the changing industrial environment. Others represented modern life and nature using color, shapes, and abstract forms. Many artists were inspired by new developments in American architecture, industry, and technology, and searched for new forms of cultural expression that celebrated American values and the phenomena of contemporary life.

Artist as Observer

The Modern World

Charles Demuth and Joseph Stella both strove to depict the inventions of modern life in the early twentieth century. Both artists were excited about the stunning achievements in architecture and industry, and were particularly interested in the ways that new factories, bridges, and skyscrapers were changing the American landscape.

Have students look closely at The Brooklyn Bridge: Variation on an Old Theme and My Egypt. What are some similarities between the two works? What are some differences? Why do they think Stella and Demuth chose those structures to represent the modern age? What types of structures do your students think represent the contemporary world?

Artist as Observer

Moods of the Seasons

Charles Burchfield often used nature as a way to express his thoughts and feelings. Have students look closely at An April Mood. Without telling them the title of the work, ask students how would they describe the mood that Burchfield created in this painting. Is this a place they would want to be? Why or why not? Reveal the title of the work to your students, adding that Burchfield wanted to portray the struggle between the end of winter and the beginning of spring. Do they see that here? Where?

Ask students to pick a month of the year to create a mood painting or drawing. What are the elements of the month that they want to portray? How might they try to create that mood on paper?

Artist as Experimenter

Moving Sculptures

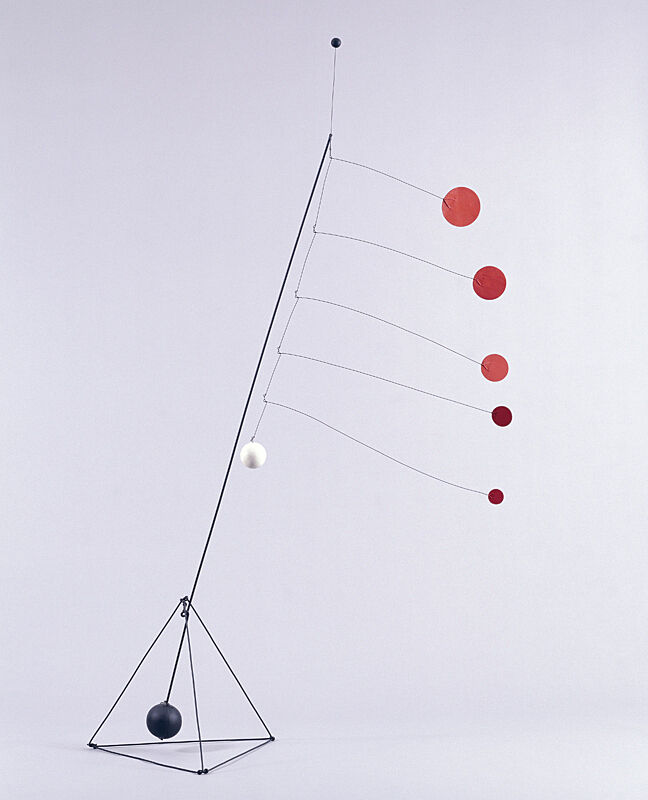

In 1930, Alexander calder visited the Paris studio of Dutch artist Piet Mondrian, where he was intrigued by a group of colored cardboard shapes pinned to the studio wall. The encounter inspired calder to start making abstract sculpture and prompted him to create the first abstract sculptures that moved. He carefully planned out his moving sculptures before he built them. He thought about how the object would move and what kinds of lines or shapes the different parts would make while in motion. These experiments would eventually lead to calder’s invention of the mobile.

Looking closely at Object with Red Discs, ask students to choose one part of the work to focus on. How would they imagine the sculpture might move? What would happen to the rest of the sculpture? Have students share their ideas with other students to see how they might have imagined the sculpture moving differently.

Objectives

Enable students to reflect upon and discuss some of the ideas and themes from the exhibition American Legends: From calder to O’Keeffe.

Have students further explore some of the artists’ approaches through art-making and writing activities.

Ask students to reflect upon what inspires them when they create works of art.

Artist as Observer

Sketches from Everyday Life

Edward Hopper often sketched scenes from everyday life, and used them to make his paintings. Hopper lived at 3 Washington Square in New York’s Greenwich Village for most of his adult life, observing what was around him and often making sketches. The building in Early Sunday Morning is based on a low, nondescript structure on the west side of Seventh Avenue between 15th and 16th streets that he once called “7th Ave shops.” Have students take a close look at Early Sunday Morning and discuss how Hopper represented his neighborhood.

Over the course of a week, have students create a photo journal of their everyday life, such as the places they go, the food they eat, and/or the friends they hang out with. Challenge students to take photographs from unconventional or unique perspectives. At the end of the week, have students download the pictures off their camera or phone and create a digital collage of their week. You and your students may consider using Instagram, PowerPoint, or Photoshop to edit and share images. What do the images tell us about their city or neighborhood? What do they tell us about the experience of being a young person today?

Artist as Experimenter

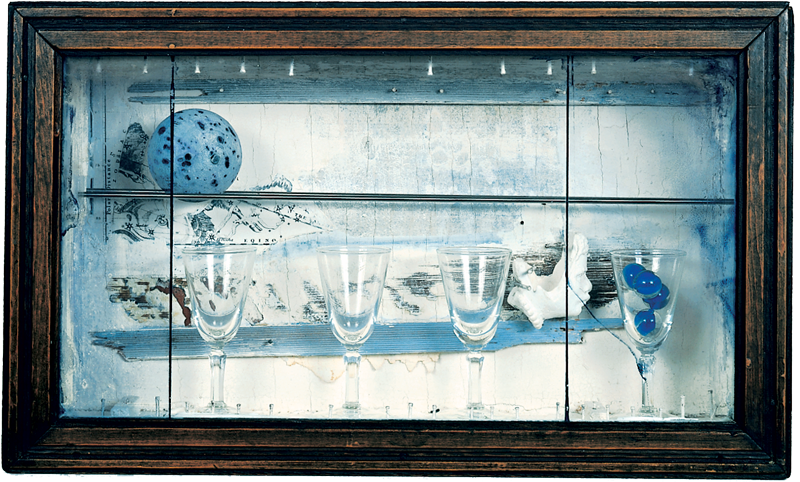

Idea Box

In Celestial Navigation, Joseph Cornell created an assemblage of objects and images that invoked the knowledge and myths that represent the night sky. Cornell was interested in scientific discoveries, astronomy, art, and storytelling, and made his works to distill and combine his thoughts on these subjects.

Ask students to think about something interesting, weird, or exciting that they recently learned. What objects or images might they use to represent this? Have students brainstorm ideas and then spend a few days collecting images and objects. Students can then create their own assemblage sculptures in small boxes that represent these new ideas.

Artist as Critic

The Essence of War

Jacob Lawrence’s War Series is based on his experiences while serving in World War II with the United States Coast Guard. Describing his intentions for the series, Lawrence explained:

“In approaching this subject, I tried to capture the essence of war. To do this I attempted to portray the feelings and emotions that are felt by the individual, both fighter and civilian.”

After your students have looked at the two images in the series, Beachhead and Victory, read them Lawrence’s quote. What emotions do they think Lawrence has tried to portray? How does he show them? What do they think Lawrence means by “the essence of war?”

Is he successful in capturing it in these works? Why or why not?

Ask students to gather images from magazines and newspapers of two current wars. How do the images of those wars compare to Lawrence’s depictions of war? How are they similar or different? What do Lawrence’s works add or leave out?

Images and Related Information

Charles Burchfield

An April Mood, 1946–55

Charles Burchfield captured the effects of seasonal changes of the landscape near his home outside of Buffalo, New York —phenomena that he also registered in his diaries. Though wild flowers and yellow-tipped vegetation are beginning to emerge from the winter-deadened earth, the overhanging clouds portend the delay of spring. Burchfield thought of An April Mood as portraying a struggle between the end of winter and the beginning of spring, in which the sky formed an “April frown.” In his journal, he described the watercolor as “A sketch of the sky & old maple trees on edge of the woods. The mood I aimed at was the anger of God —a good Friday mood.” His religious theme is implied by the groups of three clustered trees in the foreground and background, which serve as symbols of the three crosses present at the crucifixion.

Burchfield’s journals, Gardenville, April 20, 1946. Extended object label 2010.

About the Artist

Charles Burchfield

1893–1967

Charles Burchfield grew up in a small town in Ohio and studied at the Cleveland School of Art. He spent most of his life as an “inlander,” living in Salem, Ohio, and Buffalo, New York, far from the East Coast art world. Early in his development as an artist, Burchfield experimented with different styles, including everyday scenes and industrial subjects. He worked mainly in watercolor, developing a signature technique with heavy, overlapping strokes of color. Like the Hudson River School painters before him, Burchfield found spiritual meaning in nature, and by the late 1910s, he began painting visionary, deeply individualistic landscapes.

In 1921, Burchfield and his wife moved to Gardenville, outside Buffalo, where he worked as a wallpaper designer before quitting in 1929 to concentrate on his art. In the years that followed, Burchfield’s stark images of small towns and industrial landscapes earned him renown as part of the American Scene movement, together with his close friend Edward Hopper. In 1943, as he was turning fifty and as World War II was intensifying, Burchfield went through an artistic crisis, unsure of how to develop his work. He started experimenting with the lyrical, expressionistic watercolors that he had made decades earlier, enlarging them by adding pieces of paper where he felt he needed more space for an image and cutting away parts that he thought were no longer necessary. In this way, the smaller works became large watercolors that more fully expressed the beauty and spirit of nature as he saw it.

Burchfield used nature as a vehicle for expressing his inner life —his dreams, fears, fantasies, and regressions. He greatly admired the work of Flemish artist Peter Brueghel, the Italian masters, and the landscapes of French artist Gustave Courbet, traditional Chinese landscape painting, and the writings of the naturalists Henry David Thoreau and John Burroughs. In his middle age, Burchfield began suffering from lumbago brought about by his habit of painting outdoors in difficult conditions. He worked vigorously right up until the day he died of a heart attack in 1967, shortly after the opening of his eighteenth solo exhibition at the Rehn Gallery in New York.

Alexander Calder

Object With Red Discs, 1931

Object with Red Discs embodies the simple geometry and precise balance of forms that characterized Alexander calder’s early air-driven abstract sculptures. Before he began to assemble the work, calder measured out all the elements, projected the angles described when the object was in motion, and determined the arcs of the spheres as they moved, adjusting them to achieve dynamic equilibrium. Held in a delicately cantilevered poise, the sculpture’s small pyramidal base, steel rod, and thin wire branches allow the sheet metal discs and wood balls to float and move in response to air currents or touch. With his “mobiles,” as artist Marcel Duchamp dubbed these pieces, calder had the means to incorporate surprise, accident, and humor into his work.

About the Artist

Alexander Calder

1898-1976

Alexander calder was born into a family of artists. His mother painted portraits professionally, and his father and grandfather were both sculptors. Family friends recall seeing calder at age five making little figures out of wood and wire —materials that would become staples of his mature work. Nevertheless, he first pursued a career in mechanical engineering, graduating from Stevens Institute of Technology in 1919. Four years later, he rekindled an interest in art, studying with Ashcan School artists such as John Sloan and George Luks at the Art Students League in New York, and traveling to Paris in 1926. calder’s early success sprang from a playful combination of performance, art, and sculpture. In Paris, he made small, articulated animals in wood and wire and then the first figures for his miniature calder’s Circus. A friend suggested he try making art entirely out of wire. calder took up the challenge, and began making wire portraits that approximated the loose lines of a sketch in three-dimensional space. Early portraits included performer Josephine Baker and artist Fernand Léger.

In 1930, calder visited the Paris studio of Dutch artist Piet Mondrian, where he was particularly impressed with a group of colored cardboard shapes pinned to the studio wall that Mondrian continually repositioned for compositional investigations. The encounter inspired calder to start making abstract sculpture and prompted him to explore the possibilities of movement in art. He began experimenting with planes of color hanging from wire, carefully balanced and turned with cranks and motors. He called them “mobiles,” a term coined by his friend, artist Marcel Duchamp. He soon abandoned these mechanical systems when he realized that the delicately balanced mobiles could move independently, turned only by the movement of air.

In 1932 —the same year that calder showed his mobiles for the first time —he began to make another type of sculpture that consisted of metal sheets painted in primary colors and cut into abstract shapes. Artist Jean Arp named them “stabiles.” The two forms —mobile and stabile—became the bedrock of calder’s work. In the 1960s and 70s, calder focused his energies on a series of commissions for several colossal mobiles and stabiles for public spaces around the world, including the UNESCO headquarters in Paris, Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy International Airport) in New York, and Federal Center Plaza in Chicago, among others. calder died in 1976, just weeks after the Whitney opened calder’s Universe, a major retrospective of his work.

Joseph Cornell

Celestial Navigation, C.1958

Joseph Cornell was interested in the latest scientific discoveries, poring over articles and books on astronomy and regularly observing the constellations from his backyard, but in his art he preferred a simpler, more mechanical image of the universe. Celestial Navigation recalls the clockwork mechanism of an orreryan eighteenth-century apparatus that explained the solar system with miniature revolving planets. Like an orrery, the box contains moving parts: the blue ball rolls along metal tracks and the marbles can be switched from one cordial glass to another. Cornell placed these movable orbs and a broken clay pipe in the form of a human head against a backdrop of “fixed” stars, fragmentary constellations pasted onto the walls of the box. In Celestial Navigation, Cornell invokes the myths, images, and theories once used to explain the predictable yet baffling patterns of the night sky. The box presents an ordered, though perhaps not entirely knowable, universe.

About the Artist

Joseph Cornell

1903–1972

Sculptor and experimental filmmaker Joseph Cornell was born into a close-knit family in Nyack, New York. His parents encouraged his childhood love of fairy tales, art, and movies, though, unlike his sister Elizabeth, who studied with Edward Hopper in 1915, he received no formal art training. By 1917, however, his brother Robert had fallen ill and his father had died of leukemia. These events would cast a long shadow over both his life and his art. In the years that followed, Cornell briefly attended Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, but suffered nightmares and did not excel academically. In 1921, he returned to his family’s new home in Bayside, New York, where he took a job at a wholesale textile firm to help support his mother and siblings. He did not earn an income from his art until the early 1930s, and was, by all accounts, profoundly unhappy in this intervening decade, turning to Christian Science in 1925.

In 1929, his family relocated to a modest house on Utopia Parkway in Flushing, Queens, where Cornell spent the remainder of his life. He worked out of the basement after the onset of the Great Depression, when he lost his textile job and applied himself exclusively to his art. Cornell’s discovery of the avant-garde Julien Levy Gallery in the early 1930s—and Levy’s personal encouragement of Cornell’s burgeoning collage work—likewise prompted this conversion and led to his association with the Surrealist movement. While he is often described as one of the Surrealists, however, Cornell shared neither their faith in chance occurrences nor their fascination with the subconscious, the irrational, or the unpredictable.

In the early 1930s, Cornell began to fashion the signature collages and assemblages for which he is best known. They are typically small, glass-fronted boxes filled with objects and images that the artist found in local bookshops and thrift stores and which he juxtaposed in poetic, often startlingly poignant ways. The things Cornell collected were related, even if tenuously, to his favorite subjects, including nineteenth-century sopranos, the ballet, European literature, the cinema, and astronomy, though frequently they also evidenced nostalgia for his childhood. Cornell was included in numerous group exhibitions of Dada and Surrealist art, and many of the Whitney Museum’s Annual Exhibitions in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1980, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, held a retrospective exhibition of his work.

Charles Demuth

My Egypt, 1927

My Egypt depicts a steel and concrete grain elevator belonging to John W. Eshelman & Sons in Charles Demuth’s hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Painted from a low vantage point, the structure assumes a monumentality emphasized by the inclusion of the lower rooftops of neighboring buildings (suggesting the more traditional architecture of smaller family farms) at the bottom of the painting. In Demuth’s image, the majestic grain elevator rises up as the pinnacle of American achievement—a modern day equivalent to the monuments of ancient Egypt. A series of intersecting diagonal planes add geometric dynamism add a heavenly radiance to the composition, invoking the correlations between industry and religion that were widespread in the 1920s. Nonetheless, Demuth may have intended the title to allude to the slave labor that built the pyramids, intimating the dehumanizing effect of industry on the nation’s workers. Moreover, the pyramids and their association with life after death might also have appealed to the ailing artist, who was bedridden with diabetes at the time of the painting’s execution.

About the Artist

Charles Demuth

1883–1935

Charles Demuth was born in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where his family had lived since the eighteenth century. After studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts in Philadelphia, Demuth left for Paris in 1912. During his two-year sojourn, he became acquainted with many of the avant-garde European artists of the time, including Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Francis Picabia, and Marcel Duchamp.

After returning to the United States, he was introduced to photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, who quickly included Demuth in his circle of artists. From 1915 until his death, Demuth divided his time between New York and Lancaster. He drew subject matter from both locations for his work, focusing especially on the nightlife of New York and the vernacular architecture of Lancaster. By 1918, Demuth began to adopt a vocabulary of crisp lines and flattened, planar forms. This style, which later became known as Precisionism, was influenced by the fragmented forms of Cubism and Futurism but took as its subject the modern, industrial landscape of the United States.

In 1927, Demuth began a series of canvases based on the architecture of his home town, taking as his subjects the grain elevators, water towers, and other industrial structures that had been constructed in the years following World War I. During this period, he also created a series of abstract portraits of several of his friends and artist colleagues, including The Figure Five in Gold, a portrait of poet William Carlos Williams. Although he is best known for his Precisionist oil paintings, Demuth also worked prolifically in watercolor throughout his career, producing images of flowers, still-lifes, landscapes, and illustrations for stories and plays.

Edward Hopper

Early Sunday Morning, 1930

Early Sunday Morning is one of Edward Hopper’s most iconic paintings. Although he described this work as “almost a literal translation of Seventh Avenue,” Hopper reduced the New York City street to bare essentials. The lettering in the window signs is illegible, architectural ornament is loosely sketched, and human presence is merely suggested by the various curtains differentiating discrete apartments. The long, early morning shadows in the painting would never appear on a north-south street such as Seventh Avenue. Yet these very contrasts of light and shadow, and the succession of verticals and horizontals, create the charged, almost theatrical, atmosphere of empty buildings on an unpopulated street at the beginning of the day. Although Hopper is known as a quintessential twentieth-century American realist, and his paintings are fundamentally representational, this work demonstrates his emphasis on simplified forms, painterly surfaces, and studiously constructed compositions.

About the Artist

Edward Hopper

1882–1967

One of the most important realists of the twentieth century, Edward Hopper painted intimate scenes of American life in a career that spanned over six decades. From 1900 to 1906, Hopper attended the New York School of Art, where he studied painting with urban realist Robert Henri. Hopper spent three extended sojourns in Paris between 1906 and 1910, his only trips abroad. While there, he visited avant-garde exhibitions such as the Salon des Indépendants and the Salon d’Automne, but he was more influenced by the work of Edgar Degas and the Impressionists than the period’s contemporary movements such as Fauvism and Cubism.

Hopper’s success as an illustrator and printmaker during the 1910s led him to begin painting realistic scenes of urban and rural America. By the 1920s, he was rendering these subjects in his characteristically spare and direct manner, emphasizing contrasts between light and shadow and unusual vantage points through the use of windows and doorways. Hopper’s isolated figures, estranged couples, and stark rooms imbue his images with a deep sense of mystery, loneliness, and solitude. Hopper had his first solo exhibition in January 1920 at the Whitney Studio Club in Greenwich Village, a hub for independent artists and the precursor to the modern Whitney Museum. In 1924, a successful New York gallery exhibition enabled him to give up commercial work altogether and concentrate full-time on painting. That same year, Hopper married Josephine Verstille Nivison, a painter who would be the model for almost every female figure he subsequently painted.

Throughout his career, Hopper returned again and again to the same subjects. Cape Cod, where he and Jo spent their summers, inspired paintings of lighthouses, rocky coasts, railroads, and New England houses. In New York, where he lived and worked in the same apartment overlooking Washington Square for more than fifty years, Hopper depicted the everyday sites of the modern city—movie theaters, restaurants, shops, and apartment interiors. Through a poetic, cinematic use of light and architecture, Hopper invested his scenes of ordinary American life with a haunting sense of drama and desolation. While American art in the 1950s and 60s moved away from traditional realism, Hopper had little interest in contemporary movements like Abstract Expressionism or Pop art. “The inner life of a human being is a vast and varied realm and does not concern itself alone with stimulating arrangements of color, form, and design,” he said. “Painting will have to deal more fully and less obliquely with life and nature’s phenomena before it can again become great.”

Jacob Lawrence

War Series: Beachhead, 1947

Jacob Lawrence’s War Series describes first-hand the sense of regimentation, community, and displacement that the artist experienced during his service in the United States Coast Guard during World War II. Lawrence served his first year in St. Augustine, Florida, in a racially segregated regiment where he was first given the rank of Steward’s Mate, the only one available to black Americans at the time. He befriended a commander who shared his interest in art, however, and he went on to serve in an integrated regiment as Coast Guard Artist, documenting the war in Italy, England, Egypt, and India. Those works are lost, but in 1946 he received a Guggenheim Fellowship to paint the War Series. The fourteen panels of the series present a narrative which progresses from Shipping Out to Victory. In the panels, Lawrence adopted the silhouetted figures, prominent eyes, and simplified, overlapping profiles that are typical of Egyptian wall painting. And like the ancient painters, he transformed groups of figures into surface patterns, eschewing modeling and perspective in favor of the immediacy of bold, abstracted forms. In their alternation between vertical and horizontal formats, single figures and groups, and intense action and contemplation, the fourteen panels of the War Series testify to Lawrence’s belief that one cannot “tell a story in a single painting.”

About the Artist

Jacob Lawrence

1917–2000

Jacob Lawrence focused his artistic career on telling the story of the struggle of African Americans for freedom and justice from the Civil War through the end of the twentieth century. Born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, Lawrence grew up in the vibrant milieu of Harlem in the 1930s. At the age of fourteen, he began making regular visits to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and studying the techniques and pictorial conventions of Egyptian and Renaissance art, which he would later incorporate in his multi-part compositions. As a teenager, he was encouraged to pursue art by the painter Charles Alston, in whose studio Lawrence carved out a small workspace. There, he was introduced to other artists, writers, and philosophers who promoted black achievement and strong cultural identity.

In the early 1930s, Lawrence took art classes sponsored by the Works Progress Administration; he later studied at the Harlem Art Workshop. In 1937, he enrolled at the American Artists School in New York and soon had his first solo show at the Harlem YMCA. After attending classes in the mornings, he spent afternoons in the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library, where he was inspired by his readings to create the Toussaint L’Ouverture series (1937-1938): forty-one small paintings that address Haiti’s struggle for independence in the nineteenth century. Painted in tempera on paper, they anticipate Lawrence’s subsequent preference for water-based media. This series led Lawrence to embark on pictorial biographies of Frederick Douglass, Harriet Tubman, and John Brown.

In 1940 and 1941, Lawrence completed a series of sixty paintings entitled Migration of the Negro, which collectively portray the story of African-American migration from the rural South to the industrial northern states in the 1920s. First exhibited in New York, the paintings brought him national acclaim, and in 1941 he was the first African-American artist to be represented in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York. The following year, Lawrence made a series of thirty paintings depicting views of Harlem streets and interiors drawn from everyday life, and in 1946, he began work on the War Series, a narrative based on his World War II service with the Coast Guard. In the 1950s and 60s, Lawrence focused on the politics surrounding racism and the civil rights movement. Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, he spent much of his time on commissions, including murals and prints. In his later years, Lawrence returned to his earlier themes, taking up issues of desegregation in the South, among other topics.

About the Artist

Joseph Stella

1877–1946

Joseph Stella was one of the first American artists to identify and exalt the burgeoning structures and technology of urban modernity in the early decades of the twentieth century. After immigrating to New York in 1896 from the small Italian village of Muro Locano, Stella studied painting at the Art Students League and the New York School of Art between 1897 and 1900. He soon began depicting the streets and inhabitants near his apartment in Manhattan’s Lower East Side, producing vivid drawings that were published in 1905 in the periodical The Outlook. In 1908, The Survey, a social reform journal, commissioned Stella to make a series of drawings of the Pittsburgh industrial scene; the resulting studies of miners and mining towns foreshadowed his later interest in industrial landscapes.

While on an extended sojourn in Italy and France from 1909 to 1912, Stella met many European modernists, including Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and Carlo Carrà, an Italian Futurist. The work of Carrà and his Futurist colleagues Umberto Boccioni and Gino Severini, which Stella saw in a 1912 exhibition in Paris, would inspire Stella’s fascination with modern industry and his interest in expressing a sense of motion and dynamism. After his return to the United States in 1912, Stella began depicting New York City’s skyscrapers, roadways, and bridges; the Brooklyn Bridge, which he painted numerous times between 1917 and 1941, became his most iconic subject. With their towering, majestic, and interpenetrating forms, Stella’s paintings fuse the abstract styles of the European avant-garde with quintessential American subject matter to glorify the mechanical aspects of modern life. The sharp contours, planar forms, and ray lines of Stella’s architectural and industrial images align his work with the Precisionist paintings of artists such as Charles Sheeler and Elsie Driggs.

Stella’s early Futurist paintings were shown in various places in New York, including the Armory Show in 1913 and at the Société Anonyme, of which he was a charter member. By 1922, he had renounced his Futurist painting theories. For the next two decades, he moved between New York, Paris, and Italy, producing landscapes, nudes, and other representational works marked by a stylized, Renaissance-inspired aesthetic and fanciful, quasi-Symbolist imagery.

Joseph Stella

The Brooklyn Bridge: Variation on an Old Theme,

1939

To Italian-born Joseph Stella, who immigrated to New York at the age of nineteen, New York City was a nexus of frenetic, form-shattering power. In the engineering marvel of the Brooklyn Bridge, which he first depicted in 1918 and returned to throughout his career, he found a contemporary technological monument that embodied the modern human spirit. Here, Stella portrays the bridge with a linear dynamism borrowed from Italian Futurism. He captures the dizzying height and awesome scale of the bridge from a series of fractured perspectives, combining dramatic views of radiating cables, stone masonry, cityscapes, and night sky. The large scale of the work—it is nearly six feet tall—conjures a Renaissance altar, while the Gothic style of the massive pointed arches evokes medieval churches. By combining contemporary architecture and historical allusions, Stella transformed the Brooklyn Bridge into a twentieth-century symbol of divinity, the quintessence of modern life and the Machine Age.

Bibliography and links

Maxwell L. Anderson, et al. American Visionaries: Selections from the Whitney Museum of American Art. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 2001.

Robert Gober, Cynthia Burlingham. Heat Waves in a Swamp: The Paintings of Charles Burchfield. New York, Munich: DelMonico Books/Prestel, 2009.

Barbara Haskell in collaboration with Ortrud Westheider. Modern Life. Edward Hopper and His Time. Munich: Hirmer Verlag, 2009.

Barbara Haskell. Joseph Stella. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994.

Peter T. Nesbett, Michelle Dubois, Patricia Hills, eds. Over the Line: The Art and Life of Jacob Lawrence, Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2001.

Joan Simon and Brigitte Léal, eds. Alexander calder: the Paris Years, 1926-1933. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2008.

Beth Venn and Adam D. Weinberg, eds. Frames of Reference: Looking at American Art. 1900-1950; Works from the Whitney Museum of American Art. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art in association with University of California Press, 1999.

The Whitney’s programs for teachers, teens, children, and families.

The Whitney’s collection and resources for K-12 teachers.

A special area of the Whitney’s website with resources and activities for artists ages 8-12.

A site for creating online books.

A resource for creating all kinds of cards.

A content-sharing site that allows members to “pin” images, videos, and other objects to their virtual pinboard.

A user-friendly micro-blogging platform for posting multimedia content.

Text-based posts (tweets) of up to 140 characters are displayed on the author’s profile page and delivered to followers who have subscribed to them.

Credits

This Teacher Guide was prepared by Dina Helal, Manager of Interpretation and Interactive Media; Liz Gillroy, Senior Assistant to School Programs; Heather Maxson, Manager of School, Youth, and Family Programs; and Ai Wee Seow, Coordinator of School and Educator Programs

Ongoing support for the permanent collection and major support for American Legends is provided by Bank of America.

Support for this exhibition is provided by Susan R. Malloy, The Gage Fund, and Lynn G. Straus.

The Whitney Museum of American Art’s School and Educator Programs are made possible by endowments from the William Randolph Hearst Foundation and the Walter and Leonore Annenberg Fund.

Additional support is provided by Con Edison, public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council, and by members of the Whitney’s Education Committee.

Free guided visits for New York City Public Schools endowed by The Allen and Kelli Questrom Foundation.