Narrator: Here, Levine’s material is a series of cloud photographs by Alfred Stieglitz. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Stieglitz was not only a photographer but a gallerist and a magazine publisher. He used his position to promote modern painting, and to make a case that photography was a legitimate art form. He photographed clouds partially out of a desire to create images whose depth and interest could rival that of abstract painting.

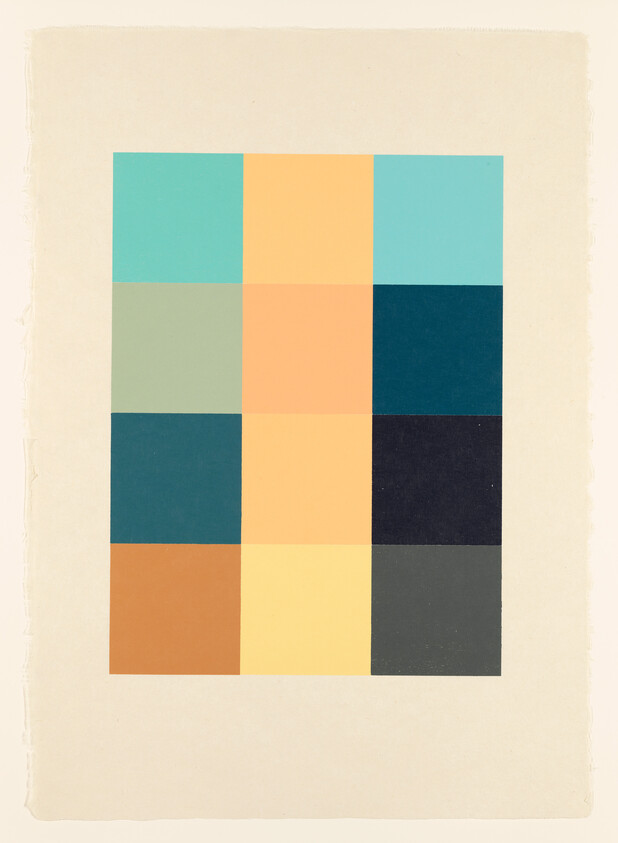

In her Equivalents, Levine has broken Stieglitz’s images into grids, taken a measurement of the tonal variation within each square, and calculated the average tone of each block. Thomas Crow.

Thomas Crow: So, she turned Stieglitz's Equivalents into a series of these sort‑of mosaic or tile‑like abstract images. So in effect, she enlisted him and, by this procedure, fulfilled his aspiration that his photography had become abstract, and become abstract within another line of development or genealogy that he would not have known about.

Narrator: The title that Stieglitz gave this series is also an important part of the work.

Thomas Crow: "Equivalents" was the name that Stieglitz chose for this series, and it's a multi‑faceted word. It implies that the images are somehow equivalent to one another. It plays with the duplicative nature of photography, that it registers something outside itself with some faithful imprint.

So it's an equivalent to what one sees in the world. And it deals with status of reproduction within the world of art because, of course, the photographic plate or negative can produce more than one print.

Narrator: Levine’s work also involves many layers of meaning.

Thomas Crow: The history of the relationship of photography to abstraction, the duplicative nature of photography. The idea of translation, that is taking one technique from its relatively early history into the realm of the digital.

The rendering of digital imagery through all the printing and imaging techniques that we have now is, I think, a powerful statement of the continuing persistence and viability of early 20th century avant‑garde art into our changed media technology perceptual universe.