Cubes and Anarchy:

An Installation

Oct 13, 2011

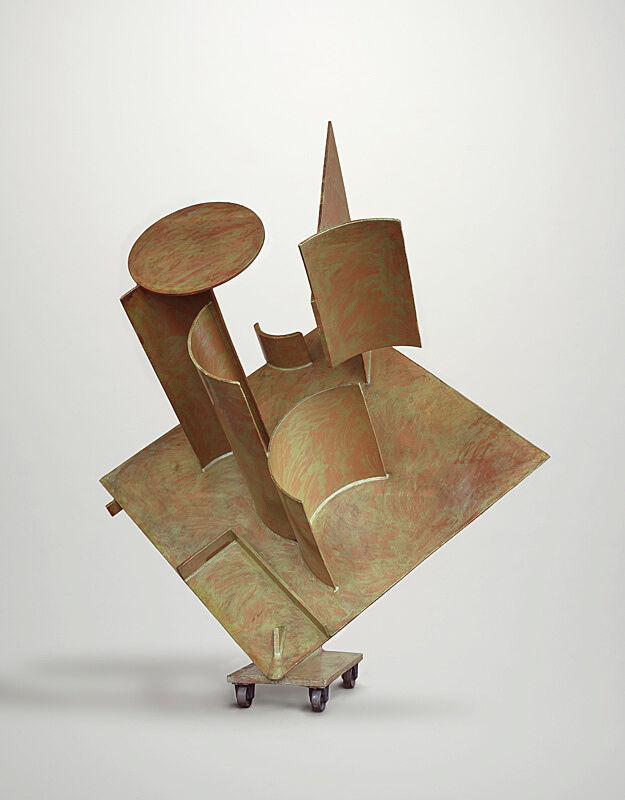

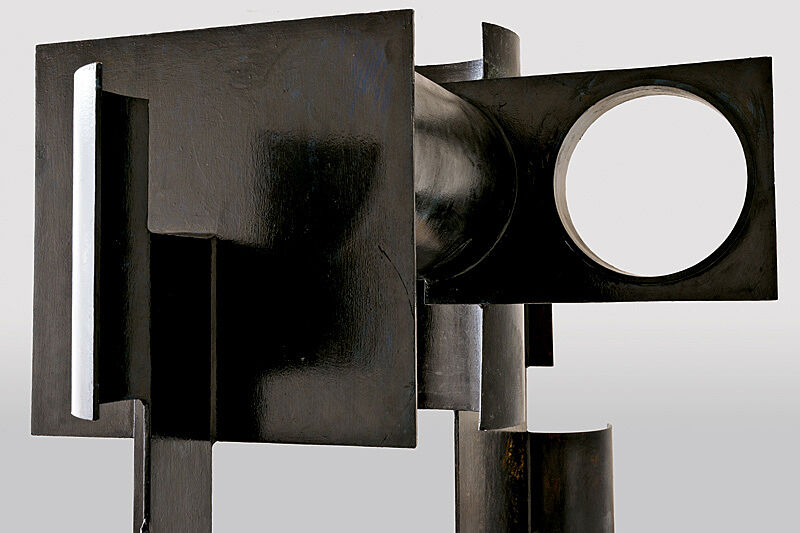

David Smith often proclaimed, “I belong with the painters.” [1] While the artist’s practice has often been read as a three-dimensional strain of Abstract Expressionist painting, the late work he is best known for differs in the most literal sense: the objects are massive, stainless steel sculptures. These pieces account for nearly half of the approximately sixty works currently on view at the Whitney in David Smith: Cubes and Anarchy (on view through January 8, 2012).

While the works themselves are awe-inspiring, the logistics of installing an exhibition like this inevitably require extraordinary planning, a little luck, and a lot of hands. Curator Barbara Haskell worked closely with artist Charles Ray, whom she invited to consult on the installation process, and Peter Stevens, the executive director of the Smith Estate. This collaboration led to the unconventional decision to bring many of Smith’s paintings, drawings, and his rarely exhibited photographs into dialogue with his later sculptural pieces.

Between the organizing museum, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and the Whitney, registrars, couriers, art handlers, conservators, and exhibition designers also play an integral part in orchestrating and executing the process. Once the loan forms, deliveries, and couriers—works on loan are often personally escorted to a show’s venue—have been painstakingly coordinated for each piece, the real fun begins on the gallery floor. A very tight schedule allowed just two weeks for installation.

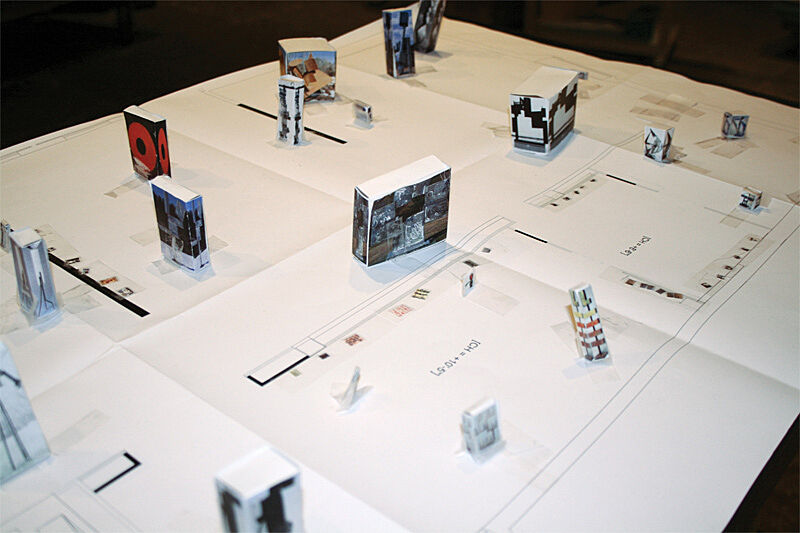

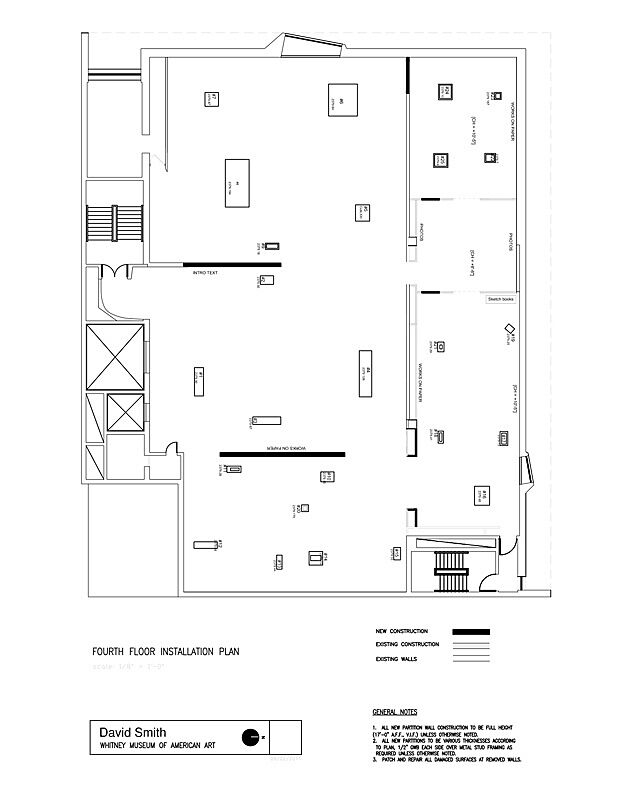

“Individual sculptures need to be placed in their final spot during each courier’s appointment,” says Curatorial Assistant Katie Josephson. “With painting exhibitions we can work around this by making large paper cutouts the size of each framed work and taping them to the wall in their appointed space, so that we can get a visual sense of how each room will be laid out even before each piece arrives. However, this practice is not effective for large-scale sculpture because we have no way of adequately demarcating the three-dimensional space that the work will take up.” Instead, Haskell and Josephson worked with exhibition designers to use CAD (computer-aided design) software to create a tentative floor plan before installation began. They also constructed a physical 3-D diorama with to-scale paper mockups that they manipulated as works came in.

Then of course there are the works of art themselves. As the registrar assigned to the exhibition, Melissa Cohen is one of the staff members entrusted with the care of the art objects during their time in the Whitney’s galleries. Over the installation process, Cohen completed meticulous condition reports on every work in the exhibition, and took further notes on the packing and handling of each object: “It isn’t as simple as ‘pulling a sculpture out of a crate.’ Consideration needs to be given to how you are going to move it off of the bottom of the crate and how it is going to travel the six inches between the bottom of the crate and the floor,” she describes. “Simply because sculptures are large does not mean that they are not extremely fragile. The surfaces of these sculptures are delicate and must be treated with care.”

The unique constraints of the Whitney’s building add an additional element to the already challenging process. Every piece on display in the Marcel Breuer–designed museum has to enter and exit the exhibition space through the Lobby and the large elevator—the same one that transports visitors daily into the galleries. This means that art preparators must carefully consider a work’s weight and size to determine if it is too large for the building, although occasionally works may be uncrated in the Lobby during hours the Museum is closed to the public, so that they can more easily enter the elevator car.

The sheer number and size of the crates necessitated that the bulk of the works be split into two shipments over two weeks, with individual crates accompanied by couriers also arriving during that period. One piece, the large and heavy painted steel sculpture Zig IV (1961), could not be installed until the day before the exhibition’s opening. To finalize the positions of the other works in the same gallery, all brought in by courier and many weighing over 2,000 pounds, Whitney art preparators created a near-scale cardboard model of Zig IV, just five inches off in dimensions from the original work, to stand in for the piece during the installation process.

“I am very lucky to have sculptors on the crew that can rise to the occasion,” the Whitney’s head preparator, Joshua Rosenblatt, says proudly of the detailed reproduction, which turned out to be quite impressive in its own right. After all, it’s this kind of behind-the scenes ingenuity that makes exhibitions like Cubes and Anarchy possible.

[1] David Smith, quoted in David Smith by David Smith: Sculpture and Writings (London/New York: Thames & Hudson, 1968), 106.