The Whitney Beekeepers

Apr 22, 2016

Above its galleries facing the Hudson River and terraces neighboring the High Line, the Whitney Museum of American Art hosts a tiny community rarely seen by staff and visitors: Two beehives sit on top of the Museum's green roof. Before moving to the new building in the Meatpacking District nearly a year ago, the Whitney bees lived uptown. The Museum's director Adam Weinberg initiated the informal program at the Breuer building on Madison Avenue in 2010, as soon as the practice became legal in New York City.

On the Upper East Side, the bees had Central Park at their disposal; in their downtown location, they benefit from proximity to the High Line. Gathering pollen, they might encounter miniature daffodils, foxtail lilies, and creeping phlox, among hundreds of other species. The yield of honey in each hive varies from season to season, from twenty pounds to 200, and every year since 2013, nearly all of the limited supply has been available for purchase at the Museum shop.

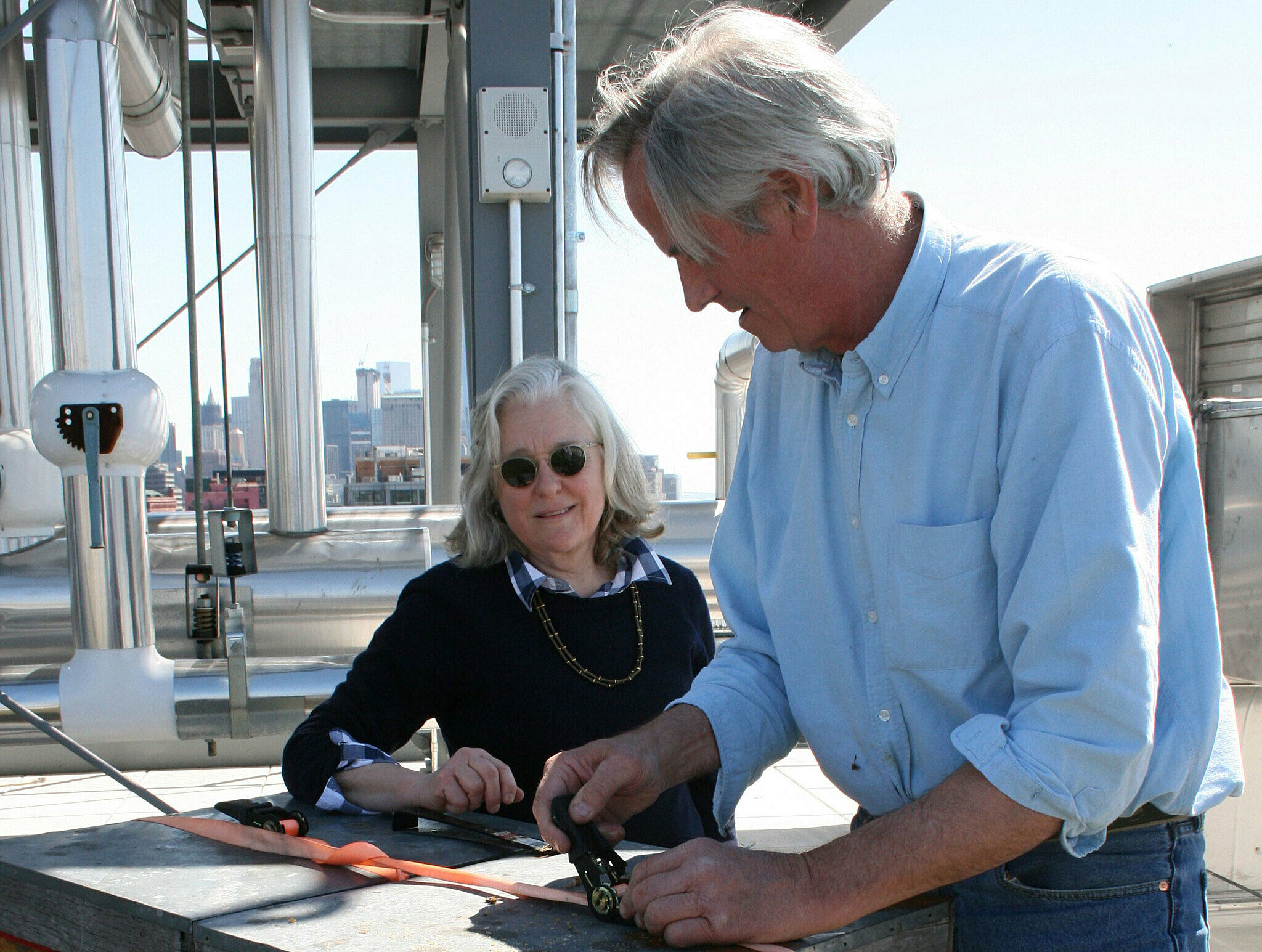

The Whitney's honey has been named one of the best in the city—CBS New York noted “citrus and hay echoes" among its characteristics—and last year, the Museum won first place in the “Battle of the Bees,” a blind tasting hosted by the Waldorf Astoria and judged by a panel of chefs and food editors. Amid these accolades, the two people responsible for tending to the hives, Chucker Branch and Christine Lehner, are quick to deflect praise. Instead, the beekeepers credit the rich floral environment near the Museum’s lower Manhattan site: “We don’t have any control over what the taste of our honey is," they said. "it’s what's in the area, nectar-wise.”

Branch and Lehner are married, and they start each morning with honey in their coffee, twenty miles north of the Whitney in Hastings-on-Hudson. In the evenings, they use honey as a topping on desserts. Lehner offered this characterization of their work together: “The way I like to put it is that Chucker does all the work and I do all the reading about bees.” The couple began beekeeping in 2004, after a dinner party guest suggested they join a bee club, the Back Yard Beekeepers Association in Connecticut. They started their first hive six months after Branch enrolled in a course there, and added two more soon after. Now, in addition to tending to their own apiary, “Let it Bee,” they are responsible for the two hives on the roof of the Whitney.

In order to produce the purest possible honey and wax, Branch and Lehner never chemically treat their hives, an approach that requires patience and dedication. Their enthusiasm for bees has flourished over the past decade as both have maintained separate careers, Lehner as a writer and Branch as a builder. “The more you learn about bees,” Lehner said, “the more interesting they become. . . . Bees are a little bit of a canary in a coalmine. If something goes terribly wrong with the bees, then we need to be worried about everybody else as well.” According to Branch, city bees require a special kind of care. “I’m not interested in having them swarm in midtown Manhattan. I try to keep a close eye on them, especially in the spring, to make sure they’re not building up too quickly.”

Despite their careful attention to the hives, Branch and Lehner are unsentimental about their work. The lifespan of a honeybee in the summer is brief, about four weeks, Branch explained. “Every time I visit the hives on the Whitney, there are different bees there.” Lehner added, “When you think about bees it makes more sense to think about the hive as a whole, rather than the individual bee. The bees operate as a unified organism, and their goal is to keep the hive healthy.” Still, the bees are easy to personify. Noting the prolific production of a typical queen—laying approximately 1,500 eggs a day during the high season—Lehner said, “it’s no slouch of a job.”

This winter was the Whitney bees’ first in their new home. After being removed from the roof of the Breuer building on Madison Avenue, they “wintered out in Hastings” with Lehner and Branch in 2014, and finally settled in at 99 Gansevoort Street in the spring of 2015. The beekeepers planned this latest relocation to coincide with the time of year when the hives are at their lightest, just after the bees have consumed their winter storage. Even then, Lehner remarked, “They were pretty heavy. We had to get some muscle-bound assistance. We brought our nephews.” According to Branch, “It’s a family affair.”

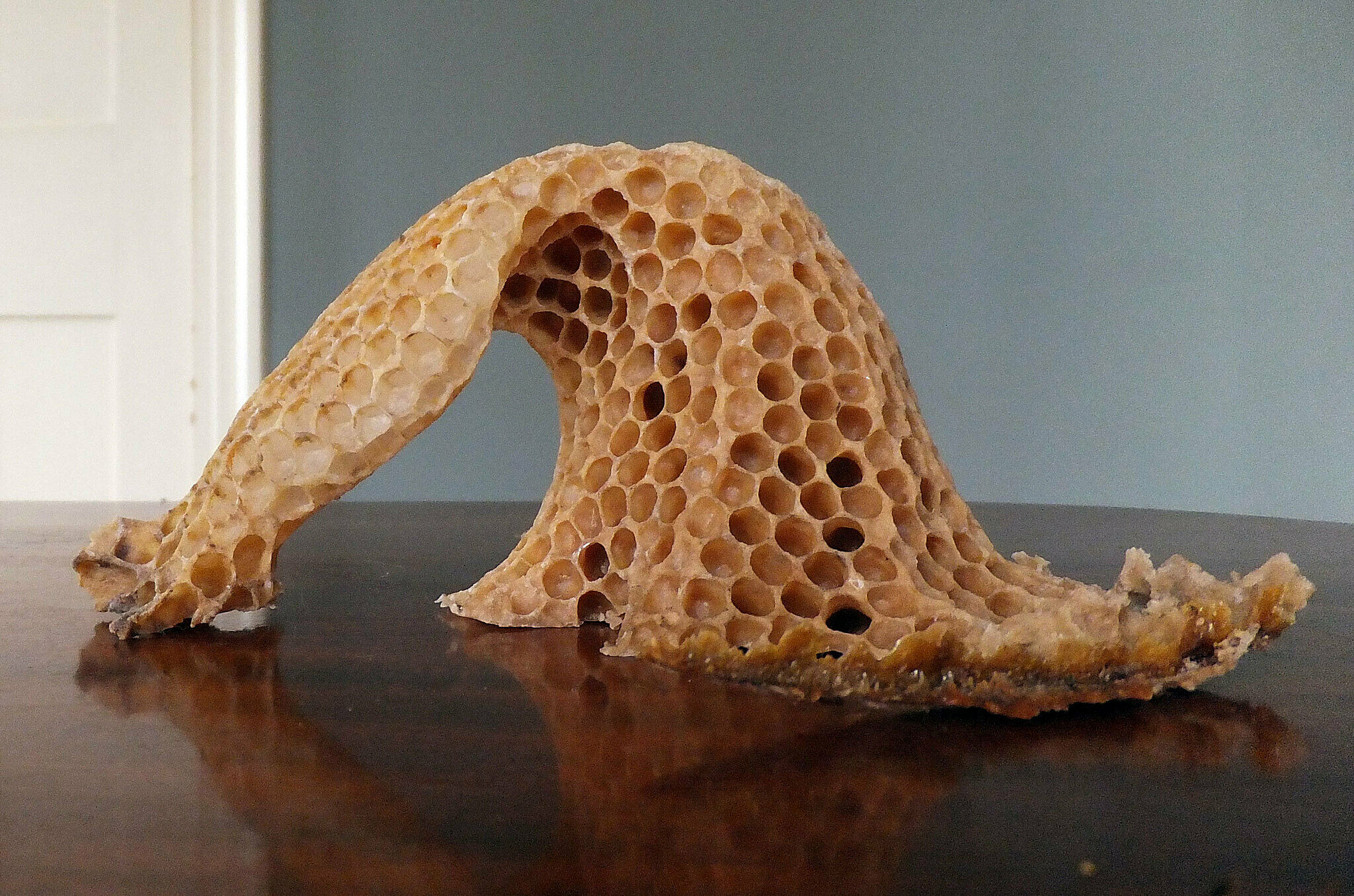

At the Whitney, the bees' production does not stop with honey. At the end of every harvest, Lehner and Branch take the capping wax, a by-product of the honey extraction, and return it to the hives. The bees clean it, and in the process, Branch said, “they create, quite frankly, nice art themselves.” The results are something like subtractive sculptures, “coral-like” shapes twice the size of a fist. Branch and Lehner display pieces from previous seasons on their mantle. This year, Branch said, “I threw a lot of the wax capping back into the hives on the Whitney, and I am curious to see what they will create there.”